Newsletter

Get the latest from Weapons and Warfare right to your inbox.

Follow Us

Explore

Avro Vulcan (1952)

Vulcan B.Mk 2 XM597, stationed at Wideawake Airfield, Ascension Island, during the Falklands campaign of 1982. This aircraft was used on both Black Buck anti-radar attacks and made an emergency landing in Brazil after a raid on the night of 2/3 June. Vulcan B.Mk 2 XM607 was one of the aircraft involved in the first of the Black Buck raids…

Referenced by West Point, Wikipedia, Army University Press (army.mil), Library of Congress (loc.gov), Encyclopedia Britannica and more.

Newsletter

Get the latest from Weapons and Warfare right to your inbox.

Follow Us

80cm K(E) railway gun

A brief history by the late Robert D Fritz Work on the giant weapon begun as far back as 1934,…

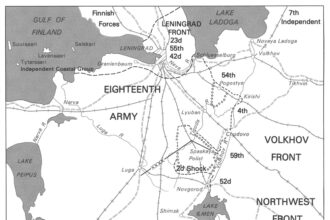

Army Group North’s Years of Hope and Frustration II

The Demyansk Salient The Soviets had managed to drive a huge bulge into Army Group Center’s front during their 1941/42…

More Cold War T-34s

T34-85. The T-34 was a medium tank produced from 1940 to 1958. Although its armour and armament were surpassed by…

Most Recent

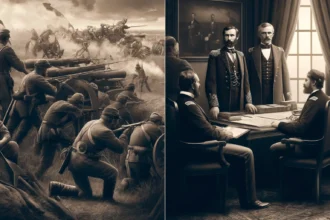

What were the South’s two main military strategies at the beginning of the war?

When the Civil War began, leaders in both the North and the South thought that it would be a short war, but the two sides had very different military strategies regarding how to bring about…

The Anaconda Plan

Following the attack on Fort Sumter and the secession by the Confederacy the Union devised a strategy to limit the length of the war. Lincoln had no desire for further bloodshed and thus wanted a…

George Washington and The American Revolution War “Grand Strategy”

The entire goal of the American Revolution including the penning of the Declaration of Independence was to gain the colonists and the newly formed American nation legitimacy internationally. The Declaration of Independence was written to…

Popular Categories

Random Reads

German Generals Fight to the Last… II

Colonel-General Gotthard Heinrici One contemporary glimpse of the thinking of a high-ranking officer based inside the Reich, away from the…

Later Panzer Divisions – East

The motorized divisions were effectively the elite of the German infantry. In 1942-43 the 14,319-strong M1940 Motorized Divisions, with two…

The Sea Battles for the Dardanelles I

Fort Seddulbahr before the bombardment on 19 February 1915. Reconstructed Turkish heavy gun site at the Dardanelles Straits before the…

Naval Doctrine 21st Century

DDG-1000 Zumwalt / DD(X) Multi-Mission Surface Combatant Future Surface Combatant. I. B. Holley concluded his 1953 seminal study, Ideas and…

More Stories

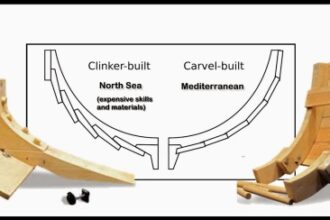

SHIPS – BEFORE THE VIKING AGE

A comparison of clinker-building and carvel-building styles. The origin of lap-strake ships The ships of the Vikings were built shell first on a backbone consisting of keel, stem and stern. The primary component was a shell of planks, fastened together with clench nails through their overlapping edges, hence the building…

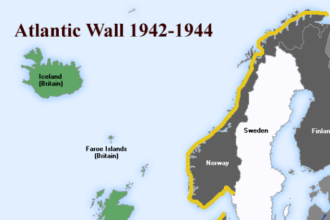

Atlantic Wall II

Many of the older fortifications on the islands were incorporated into the new defenses, after being reinforced with concrete. OT built over 8 km of concrete anti-tank walls wherever there were no preexisting granite walls along the beaches. It also installed the famous Mirus Battery of 305-mm guns on the…

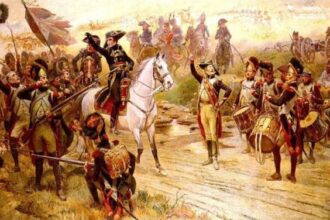

Marengo, 14 June 1800 Part I

Napoleon and the Consular Guard at Marengo, 14 June 1800, by Alphonse Lalauze. Napoleon Conferring with Desaix in Marengo, 14 June 1800 by Keith Rocco. On the afternoon of 13 June 1800 the French advance guard, Gardanne’s augmented division (5,300 infantry, 685 cavalry, and 2 guns) drove the Austrian covering…

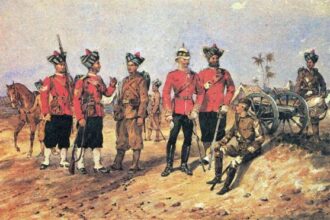

Battle of Kandahar 1880

19th Bombay Native Infantry: Battle of Kandahar on 1st September 1880 in the Second Afghan War As the British prepared to withdraw their army from Afghanistan, a column was ambushed and wiped out at Maiwand. The survivors fled back to Kandahar where they and the British garrison were besieged by…

Soviet NKVD II

In a short period of time, with fierce fighting raging in full swing on all fronts, 15 divisions were formed and reinforced the Soviet defences—10 of them were sent to the Western direction(243rd, 244th, 246th, 247th, 249th, 250th, 251st, 252nd, 254th, 256th), and 5 to the North-West(257th, 259th, 262nd, 265th,…

Baukommando Becker – Artillery Conversions

Alfred Becker started the war in the west with his Batterie (12.) horse powered. After reaching the first Dutch artillery depot on the way of 227. ID he equipped his Batterie and the recon element of 227. ID with motorized vehicles. Becker started to refit his Batterie with SPA’s by…

Batumi Raids

Russian line infantry during The Russo-Turkish War 1877 Foot Bashi-Bazouk The Russo-Ottoman War of 1877 – 1878 had a huge impact both on the countries involved in the conflict and the different nations living there. The 300 years of the so-called “Ottoman Yoke” did not succeed in killing the Georgian…

TSUKUBA CLASS

Ikoma at Portsmouth 1908–09 Their construction, although a clever concept, was not a new one because the Italian Navy had been building on this theme – battleship armament on a cruiser hull – for some time. This was fine in theory, but because the type was expected to face heavily protected…

Most Popular

AMPHIBIOUS ASSAULT IN BRITTANY, 1758

British coastal assault on St Cast in Brittany in September 1758. A German map, published…

German Schnellboot (S-boat)

Schnellboot S-80 torpedo boat Camo Operations with the Kriegsmarine S-boats were often used to patrol…

Lend-Lease to the USSR

American Lend-Lease supplies to the USSR 1941–45. Soviet historiography is mocked in the West, where…