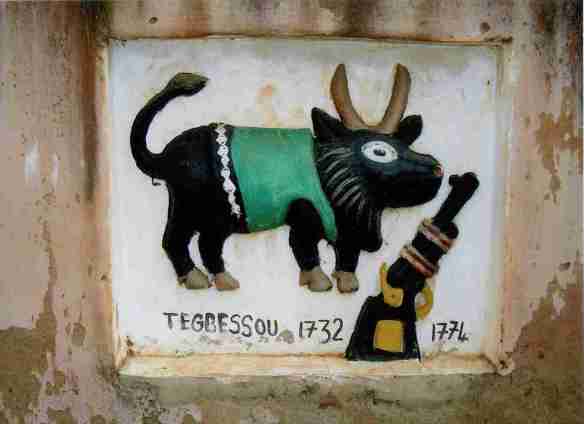

Symbol of Tegbessou was the sixth King of Dahomey. He succeeded Agadja, and ruled from 1740 to 1774.

Tegbessou’s reign was characterized by internal intrigues and a failed foreign policy; he killed many coup-plotters and political enemies, refused to pay tribute to the Yorubas, and lost many battles in the punitive raids that followed. His main symbol is a buffalo wearing a tunic. His other symbols are the blunderbuss, a weapon he gave his warriors—the first time in Dahomey that the royal army had ready access to firearms—and a door decorated with three noseless heads, a reference to his victory over a rebellious tributary people, the Zou, whose corpses he mutilated.

“Proverb – ‘Once a buffalo is dressed it is very difficult to undress him.’ The buffalo is symbolic of the strength of the king. During the enthroning ceremony, Tegbessou’s enemies put an herbal potion that would cause severe itching on the royal costume, so when he put it on he would have to remove it immediately. This would have led to an on-the-spot selection of a new king. Warned in time, Tegbessou took the necessary precautions and put the costume on, hence the dressed buffalo (buffalo wearing a tunic).”

“In the early 18th century, Kings of Dahomey (known today as Benin) became big players in the slave trade, waging a bitter war on their neighbours, resulting in the capture of 10,000, including another important slave trader, the King of Whydah. King Tegbessou made £250,000 a year selling people into slavery in 1750.”

Tegbessou was succeeded by Kpengla.

#

The earliest descriptions of warfare indicate that all infantry in the region carried shields, swords and lances of one kind or another (typically called asagayas) and used arrows. Illustrations and descriptions of these weapons in the early eighteenth century show a triple-barbed pointed javelin, which could be thrown accurately from about 30 paces. Shields were very large, four feet long and two wide, so that they covered the whole body. These shields were made of elephant or oxhide, and were proof against arrows and most javelins. For closer fighting, men carried a three-foot-long heavy sword or cutlass.6 Finally, people of the coastal areas at least used a short throwing club, like the clubs in Upper Guinea, capable of breaking bones and hurled with great accuracy in a manner resembling the throwing of a javelin. Bosman believed the people of the Gold Coast (probably Accra and Akwamu, the states most involved in this area) feared these clubs more than a musket. These weapons, supplemented by muskets in the middle of the seventeenth century, remained a constant mainstay from the earliest descriptions until well into the eighteenth century.

The initial organization of Allada and its neighbours in the late seventeenth century probably reflected the earlier periods as well, in which the structure of armies and their tactical organization was designed to lead to a hand-to-hand encounter. An account of the 1690s describes Allada’s armies as being organized in tightly disciplined companies for parades or marches, but when they were deployed in the battlefield they spread out like “groups of sheep”. Indeed, their parade order was remarkable, if one believes the plates that accompanied the account of Desmarchais, which shows the coronation parade of the king of Whydah in 1725. In the picture, the army of Whydah is shown in dense formations that would have made a European proud, with musketeers and pikemen in separate formations.

But the parade order was probably only to facilitate rapid marching, for the soldiers clearly did deploy into loose companies, “great platoons without ranks and without order” once in the presence of the enemy. If they had superior numbers they sought to envelop their opponent’s formation, but when armies of equal strength met each other they did little beyond probing attacks, each withdrawing without fear of being pursued; only, in fact, when a complete defeat was imminent did they fight bravely and desperately. Another early-eighteenth-century French visitor thought small mercenary forces from the Gold Coast refugees could defeat Whydah, even though the king could allegedly raise huge armies, because the dispersed deployment meant that they fought without order, and were thus weak and vulnerable. Each unit fought separately, and by the early eighteenth century they were beginning actions with a phase of musketry, although it was conducted at considerable range, so that shots were often ineffective, though they could penetrate the shields, probably their most important function. Musketry was often considered intense if a few people fell. This early phase of musket fire probably came from skirmishers posted forward, since musketeers did not carry shields and were thus not expected to engage in the later phases of battle. In many encounters, if generals judged that the issue could not be decisively decided and opted to withdraw, they might not go farther than a musketry skirmish.

There were times when armies did engage each other closely, so that an archery phase began after the musketry phase, and the “sky is obscured by arrows” as they advanced, probably, like their counterparts in the Gold Coast, shooting them in an overhead trajectory. Then the forces commenced a closing attack, as the infantry hurled their javelins, while covering themselves as best they could with their shields, and at last they closed completely for hand-to-hand fighting with sword and cutlass. The loose formations of which the European observers complained were probably designed to give room for the soldiers to fight hand-to-hand, while at the same time reducing the chances of the javelins and other missile weapons hitting their targets, since attacking loose formations required aiming. Once battle was joined, “no one then thought of giving or receiving quarter” until one side or the other broke. Then, throwing aside their arms, the defeated fled as best they could, vigorously pursued by the victors, who sought to capture, garrotte or enslave as many as possible.

Tactics of the armies of the region went through a slow evolution as weapons changed, moving as elsewhere from an ultimate reliance on handto- hand fighting to looser organization and much more dependence on firepower from muskets. Gunpowder weapons were employed quite early in the region. As elsewhere, Portuguese mercenaries provided the earliest of these. They were already serving in Benin in about 1515, probably with guns, and in 1516 the king of Benin seized a Portuguese bombard for his own use. When Andreas Josua Ulsheimer came to the Lagos Lagoon region in 1603, his captain was recruited by the king of Benin to use their artillery to assist in bombarding a rebel town in the area. The Dutch force with two large guns joined some 10,000 Benin soldiers in the assault, which succeeded when the main gate of the walled town was forced after half a day’s bombardment.

In the sixteenth century, though, these gunpowder weapons were virtually always used by Europeans and for specialized purposes, especially in sieges. African armies began importing and using gunpowder weapons in their own forces only by the mid-seventeenth century. A few Dutch muskets were being deployed by soldiers in Warri’s army or navy alongside arrows and javelins by 1656. In 1662, visiting Capuchin missionaries noted that the king of Allada had muskets stored in his palace. The Sieur d’Elbée, visiting Allada in 1670, witnessed a parade of troops and noted that as well as spears, shields and swords, the men also carried “muskets in good order”.

By the time an “unhappy war” broke out between Offa and its neighbours in 1681, large supplies of gunpowder were considered crucial for continuation. However, these weapons were much slower in displacing the more traditional weapons, for in all these instances gunpowder weapons continued to be carried and used side by side with clubs, shields, swords, lances and archery, both in the Gap and the Delta, where a visitor to Old Calabar in 1713 noted no firearms among its troops.

It was some time around the second quarter of the eighteenth century that gunpowder weapons came to dominate the field. Whydah had more muskets than other coastal powers, but they were still not the dominant missile weapon for them, being employed, as in the Gold Coast, as a skirmishing weapon in the early stages of combat. The emerging kingdom of Dahomey, which invaded the coast in 1724 when it attacked Allada, started using firearms more often and dispensing with other weapons. As early as 1727, when King Agaja of Dahomey wrote to King George I of England, he noted that, “I am gret admirer of fire armes, and have allmost intirle left of the use of bows and arrows, though much nearer the sea we use them, and other old fashioned weapons,” such as the throwing club and javelin. He expressed a strong desire to replace his “old fashioned weapons” as soon as possible if he could learn to manufacture powder or firearms. The army that William Snelgrave reviewed that same year still carried shields and swords, although he noted that they were largely armed with firearms.

Gunpowder weapons proved to be of some value to Dahomey soon after. The cavalry armies of Oyo that invaded Dahomey in the period between 1728 and 1747 were entirely horsed, using bows and arrows as their missile weapons, lances and “cutting swords”. When they met Dahomey’s troops the gunfire frightened the horses, preventing them from making a home charge. As a result, Dahomean infantry was able to stand in the field against them, though defeating them proved more difficult.

In the following years, however, gunpowder weapons did become general. When the navy of Warri received the Portuguese vessel that brought Capuchin Domenico Bernardi da Cesena in 1722, many carried muskets and pistols, and fired salutes with their guns. By the 1780s the musket had replaced all other missile weapons, and the sword had become for the most part an officer’s weapon. The soldiers of a great alliance of small states lying along the Volta that fought alongside Danish forces in the campaign against Agona were equipped solely with muskets, carrying only a variety of daggers as a personal weapon.

The evolution of tactics in all musketry wars is revealed clearly in Isert’s detailed account of an action between an allied force of some 4,000 troops and a probably smaller force from Agona on 11 April 1784. The allied force advanced in a dispersed order, by platoons of 25–100 men, across a field against an enemy who had posted themselves on the edge of a forest. Pickets were deployed to find and fix the enemy and then platoon after platoon advanced at a run, stopping some 50 paces from their opponents to form a single firing line, stepping back to reload after each round. The larger engagement divided into a number of local affairs, but as the Agonas had many of their forces concealed in the woods they were able to emerge unexpectedly and threaten the more advanced of the allied troops. To meet these threats, reserve platoons, held back from the first assault, were committed as needed, and the fighting continued until nightfall when both sides eventually withdrew from the field.