Communist soldiers in Vietnam could be divided into three classes. There were the regular uniformed North Vietnamese Army troops who fought in established units and formations. Most NVA soldiers were recruited from the urban conglomeration around Hanoi or from villages in the rural paddy areas of the northern plains. NVA troops were no more naturally suited to the rigors of jungle warfare than were the city and farm boys drafted from Middle America. In addition to the NVA, there were regular VC troops who were full-time guerrilla soldiers. And last, there were local VC troops who stayed at home and fought a clandestine war at night and farmed by day.

The local VC varied widely in their military capabilities. In some areas they were highly regarded when they were well led, but for the most part, they were not considered a major threat. Their training was quite elementary and they were sparsely equipped with a variety of small arms, grenades and explosives. Their equipment ranged from captured American and old French equipment to Soviet pattern automatic rifles. In a fight, the local VC almost always lost. They did not have the training, the equipment or the numbers to do much damage, although on very rare occasions, they would mass to company and even battalion strength to strike at vulnerable positions. The local VC did a great deal of damage by laying booby traps and mines as well as pungi stake traps on likely enemy trails. The VC proved to be extremely cunning in this form of warfare and what they lacked in the traditional military skills, they more than compensated for in waging this type of combat. Local VC forces were also often used to act as a screen through which NVA or regular VC units would withdraw after a major action. They were particularly well suited to this task because of their intimate knowledge of the local area and their ability to blend in quickly with the populace. Perhaps more important than their military strength, the widespread presence of local VC cadres provided a compelling political alternative to the peasants of South Vietnam. The very fact that an indigenous VC organization existed served to divide the peasants loyalty and robbed the Southern forces and their allies of the overwhelming support they needed to be successful in this kind of guerrilla war.

The regular VC were in fact professional guerrillas. Forty percent of them were recruited or impressed in the South, endured a grueling march north to be trained and marched south again to serve in an area different from their home. The remainder were specially trained North Vietnamese. The regular or “hard core” or “main force” VC as they were often called were capably led by dedicated professional officers and NCOs. For the most part, their senior officers had experience fighting the French and all of them had been around war long enough to give them a healthy collective measure of battle experience. Like their local counterpart, most of the Southerners had the outlook of seasoned veterans before they joined. The regular VC soldier was stringently, but contrary to popular belief, not harshly disciplined by his leaders. Nonetheless, his morale fluctuated. In 1966, a thousand of them were defecting to the Americans or other allies every month. By 1968 their morale and discipline had improved dramatically and this desertion rate dropped to almost nothing.

The regular VC were physically and mentally tough soldiers. They were prepared to endure deprivation and their standard of field craft was extremely high. They could wait silently in a jungle ambush for long periods of time, carry heavy loads for long distances and spend hours silently stalking an enemy position. They were adequately trained when they arrived in their area of responsibility in the south and their training continued when they were not actively engaged on operations. As a rule of thumb, while serving in South Vietnam they received two thirds of their training in technical and tactical skills and one third in political propaganda. They spent a great deal of their time training at night and proved to be a very dangerous opponent after dark.

The regular VC soldier was well supported by an elaborate infrastructure. There were troops responsible for pay, supply services, training and political cadres, taxation of VC controlled areas and in some instances, primitive medical services. They had a definite organizational structure, clear rules governing promotion policies and even a precisely defined grievance system. However, it should be stressed that in the VC organization, there was no administrative fat and the ratio of fighting troops to service troops bore absolutely no resemblance to that of a modern Western army.

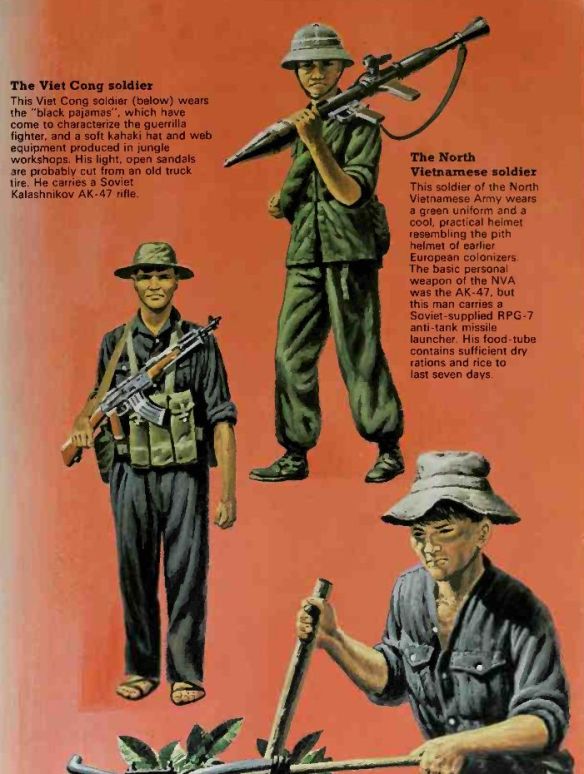

The regular VC was better equipped than the local VC although their equipment scales were extremely light. The standard weapon was the AK–47 assault rifle. They had light and medium mortars, grenades of Chinese and American manufacture, Soviet sniper rifles, light and medium machine guns, B40 rocket propelled grenades and various explosives and demolitions for use in the construction of mines and booby traps.

By 1968 there were between seventy and eighty thousand VC operating in South Vietnam. Many lived in villages within the allied area of influence; many more lived in rudimentary camps and villages in the jungle and others operated out of fantastically elaborate tunnel complexes. Some tunnel complexes were found to be as much as 30 kilometers in length. Most tunnel systems in South Vietnam had been developed according to a central plan and were prepared and improved on over several years.

Main force VC were by no stretch of the imagination paragons of austere military virtues. And certainly, unlike the way they were portrayed in their own propaganda, they were not stoic and essentially noble peasant warriors. They were tough, dedicated and cunning but they were also vicious and utterly ruthless with their own people as a matter of policy. For the VC, mass murder was an accepted tactic, not a disciplinary failing and in this respect they were altogether completely different from their American opponents. Throughout the war, the VC executed scores of thousands of Vietnamese civilians when they took control of an area. For years they waged a bloody and continuous program of assassination of village chiefs, local officials, schoolteachers and any other figures of importance who could have even the most remote connection with the Southern government.

The North Vietnamese Army was composed of long service conscripts, who unlike the American soldiers fighting against them, were in for the duration of the war. The NVA soldier was well trained and well disciplined. A considerable period of his training was spent inculcating in him enthusiasm for communist ideology and patriotic fervor. He was certainly a patriotic soldier and he took enormous pride in the fact that his army had already convincingly defeated the French. He was prepared to do the same thing to the Americans and what he considered to be their South Vietnamese puppets. Throughout the war it was often reported that the North Vietnamese soldier was an unwilling and sullen conscript who was kept in the army by brutally fanatical officers and NCOs, but the evidence against this view is overwhelming. Defections from the North Vietnamese Army were never great in terms of relative numbers and this was despite the hardship and privations suffered by the northern soldier.

The North Vietnamese soldier certainly must have suffered a great deal. We can only guess at what the NVA non-battle casualty rate was from disease, but living in the jungles of South Vietnam, Laos and Cambodia under the conditions that pervaded, it must have been very high. His discipline was extremely strict and the penalties for disciplinary lapses were savage and immediate. Nonetheless, this does not mean that he was motivated solely by fear of his leaders. To accept the viewpoint that the NVA Regular was a completely unwilling military slave is not consistent with his battlefield performance. His initiative, tenacity, courage and stamina were maintained for years in the face of appallingly heavy casualties.

From the time he began his trek south down the Ho Chi Minh trail the NVA soldier lived a life of danger coupled with severe physical and mental stress. He carried his assault rifle and personal ammunition, a water bottle, Chinese stick hand grenades, a spare khaki uniform, a plastic poncho, a hammock, pictures of his family and girlfriend and frequently, a diary. In addition he would also carry a heavy burden of ammunition or bulk supplies of food to be stockpiled in the south for future operations. Once in the south, he spent the largest part of his time hiding in the jungle or in hand dug caves and tunnels. On small unit patrol actions and ambushes he usually gave a good account of himself but when he was led forward for conventional offensive operations, he invariably suffered far greater casualties than he inflicted. Yet despite this, he soldiered on and eventually triumphed.