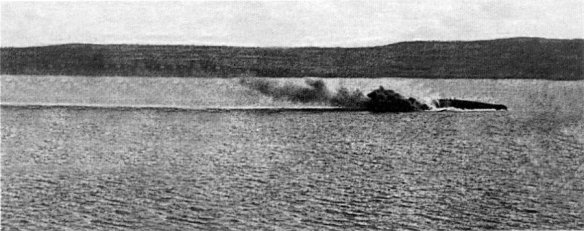

The last moments of the French battleship Bouvet which struck a mine in the Dardanelles on March 18, 1915, capsized and sank within two minutes, killing over 600 men.

British battleship HMS Irresistible abandoned and sinking, 18 March 1915, during the Battle of Gallipoli.

By the end of 1914, the war in France had settled into a deadlock. With both Allied and Central powers anchoring their flanks on the English Channel and the Swiss border, defenses in depth were the rule. Some in the British government believed that the war might have to be won elsewhere, or that at least the Allies should pose a sufficient threat to make Germany withdraw troops and weaken their position in France. The Russians were having little success against Germany, so that front seemed unlikely to bring any luck. First Lord of the Admiralty Winston Churchill suggested an attack against Germany’s ally, Turkey. Turkey had its fingers in many pies: a new attack against the Caucasus to threaten Russia, an abortive move against the Suez Canal, and a defensive stand against a British force moving up from the Persian Gulf. Certainly, Churchill argued, a direct thrust against the Turkish capital at Constantinople should be enough to disrupt the Turkish military and panic its government into surrender. Secretary of State for War Lord Kitchener blocked any attempt to siphon off soldiers from the fighting in France, so Churchill stated that the victory could be won by the Royal Navy alone. Churchill proposed to destroy the forts that guarded the Dardanelles, the passageway to Constantinople and the Black Sea, after which a naval force could cruise up to the Turkish capital and bombard the city at leisure. He was certain that naval gunfire could destroy the forts. When the Turks had joined the war the previous November, a British naval raid against the straits met virtually no resistance from the obsolescent Turkish defenses, so the Turkish government should surrender at gunpoint with little trouble. Once Turkey had been removed from the war, Churchill argued, a direct supply line to and from Russia would be open, and the Balkan States that had allied themselves with Germany should cave in quickly to Allied pressure and threaten Germany’s other ally, Austria-Hungary. The British Cabinet reluctantly approved.

The force that gathered at the Greek island of Lemnos in February 1915 was made up of both British and French battleships. Though they were allies, the French had no intention of allowing Britain to control the straits alone. Under overall British command, the armada sailed to the mouth of the Dardanelles and began bombarding the forts. Little did the British know that the previous November’s raid had alerted the Turks to the weakness of their defenses and, under the direction of German adviser Field Marshal Colmar von der Goltz, they had been working steadily ever since to improve their fortifications.

The Allies began bombarding the forts, and were surprised to find no return fire until they drew close to shore. The first few hours of shelling had had little effect, and the Allies withdrew to wait out some bad weather. When they returned on 25 February, the shelling continued with irregular results. Some forts were silenced by the naval guns, then blown apart by landing parties. Others survived erratic shelling with little problem. Turkish return fire was bothersome, but not dangerous. It was not artillery fire, however, that turned the tide, but mines. The Allies knew the Turks had sown the straits with mines, and had brought along minesweepers to take care of the problem. But the art of minesweeping was in its infancy, and a secret Turkish operation in a previously cleared area proved the Allies’ undoing. On 18 March the ships sailed in to run the length of the straits and ran straight into the new minefield. Within a few hours, three ships were sunk and three were badly damaged. The naval forces withdrew. Had they pushed forward past this point, the mission may well have been successful, because the Turks were almost out of ammunition. The navy had failed, and called for the army.

Oddly enough, the government in London had been preparing forces for the campaign. Kitchener’s early resistance turned to grudging acceptance, and 75,000 men, many from the Australia and New Zealand Army Corps (Anzacs), were assigned to land on the Gallipoli Peninsula. Sir lan Hamilton was given command of the operation, though he was allowed little time to prepare; the government wanted results in a hurry. Because Hamilton found the base at Lemnos unfit for a major operation, he redirected the troops’ convoys to Alexandria, Egypt. The ships had to be unloaded and reloaded in an attempt to repair the haphazard loading done in England. Finally, the expedition got under way in mid-April 1915. Hamilton decided to land forces at five spots along the peninsula, plus a French diversionary force on the Asiatic side of the mouth of the straits. This multiple landing would allow the troops to swarm over the peninsula and capture the forts, thereby giving the navy the opportunity to sail by unhindered. Rarely has the expression “So close and yet so far” had such meaning in military history as it did on 25 April 1915. The Turkish defenders, though outnumbering the attackers, were mostly held in reserve at the neck of the peninsula. At some beaches, stiff resistance forced slow progress, but at others there was little or no resistance. The Turks were unprepared for multiple landings, and aggressive action would have given the Allies an easy victory. Hamilton, onboard ship, had reports from all the beaches, but he preferred to have the local commanders respond to individual circumstances. Local commanders were operating on a preset timetable, and did not take advantage of opportunities because inland advances were scheduled for later. While the British, Anzacs, and French stayed on the beaches, whether through Turkish resistance or lack of leadership, the Turks were able to reinforce. By the time assaults were made, the Turks shot down the attackers in huge numbers. The quick, easy operation soon turned into a miniature version of the trench warfare of France.

Through the summer of 1915, the men on the beaches made little or no headway against Turkish defenses, which grew constantly stronger. Reinforcements sent in August repeated the failings of April: easy landings against little resistance, followed by enough hesitation to allow the Turks time to react. The 35,000 men committed in August ended up stuck on the beaches under punishing fire just like their comrades earlier. From beginning to end, the operation to force the straits suffered from a lack of planning and preparation. For example, the navy was sent in to capture Constantinople, though it is impossible for ships to take or hold targets on land. The amphibious operations were experimental to a great extent because the troops taking part had no previous training. Actually, the landings were successful; it was the push off the beaches that failed. The troops, both British and Anzac, were recent inductees in combat for the first time, and their lack of experience led to much confusion during and immediately after the landings. Although both Allies and Turks made mistakes, the Turks made fewer and won the battle. The Allies successfully evacuated in December.

The invasion reinforced the Turks’ morale and strengthened their resolve to support Germany. Now veterans with a success under their belts, the Turkish troops transferred to Mesopotamia to take part in the successful siege of Kut-al-Amara, in which the Sixth Indian Division was captured after the longest siege in British history. For the losing side, there are only a series of might-have-beens. As the battle took place, representatives of Britain, France, and Russia were dividing up the Ottoman Empire among them; Constantinople and the straits were to have gone to Russia, and the Russians would have attained their centuries-old dream of warm-water access for their navy. If the Western Allies could have used this passage to reinforce or resupply the Russians, would the Eastern Front have held? Would the Russian Revolution have taken place? Would the Balkan States have abandoned the Central Powers in order to grab what they could from a struggling Austria- Hungary? The future of Eastern Europe may well have been much different had the British Royal Navy in March or the soldiers on the ground in April 1915 seized opportunities that would have given them a relatively easy victory.

References: Bush, Eric, Gallipoli (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1975); Fewster, Kevin, A Turkish View of Gallipoli (Richmond, Victoria, Australia: Hodja, 1985); Moorehead, Alan, Gallipoli (New York: Harper & Brothers, 1956).