The German character has always respected practical

attainments and academic endeavour. To this day, the visiting industrialist who

goes to Germany – West or East – finds how helpful it is if he admits on his

visiting card that he is ‘Mr Engineer’ or ‘Herr Doktor’ ; education, learning,

and academic status have always been important parts of the German tradition.

In the 1930s this tendency was developed to the full.

Through the propaganda machine of the Nazi empire-to -be, the academic and the

engineer alike were esteemed as never before, and the aim of all successful men

was to enter these professions and succeed within their framework. But as the

Hitler regime came to power and began to exert its influence, there was a

subtle indeed almost barely detectable change of emphasis. The pure scientist

began to lose out of the favourable comment; the academic lost a little in

favour – but the technician, the practical man, the engineer, these began an

unprecedented climb to the greatest heights of status.

The shift of emphasis became out right bias, however, and

particularly as more and more German scientists were being discriminated

against because of supposed `racial inferiority’, many of them uprooted themselves

and fled the country altogether. By the late 1930s the change had been almost

complete: only Goring remained with any deep respect for the intellectuals of

Germany, and he used them to the full. One of his chief co-workers was a

General Milch, part-Jewish, who became Head of the Technical Office of

the Luftwaffe in due course. In spite of ‘mongrel’ background, as defined by

Hitler, Goring had this man kept in a senior position for pure intellectual

ability and practical skill.

But to some extent this anti-intellectualism of the Hitler

regime did have its desired beneficial effect, for it turned the German people

away from their almost slavish acceptance of the need for academic

specialisation, and allowed them to assume that (because of the

widely-publicised ‘inherent superiority’ of the German race) they were above

the need to specialise: they could all be conversant with the problems of

technology and the scientific society, and great pains were taken to make them

feel that – no matter how superficially – they were in on

things. Secondly, because of the drift from academic endeavour, more and more

people became technical workers, and the shift from pure research was accompanied

to a certain extent by a drift towards applied research, design, and

development. The cult of progress became established, and in the German mind it

was readily nurtured.

Germany has an equal tradition for good quality workmanship,

for discipline and for endeavour. Thus it was that many of their largest firms

were in the export field, with singularly up-to-the-minute sales equipment to

back them, and this – prophetically – included the development of munitions. The

wheels of big business soon allowed this side of the German industrial

endeavour to reach large proportions; the Germans were one of the few nations

who were in a position to supply modern, effective munitions. Why was this?

Quite simply because of their active research capacity: munition supply is one

of the branches of industry which, almost more than anything else, relies on

being up-to- date – in short, the successful munitions manufacturer must be the

most advanced technically. This and the encouragement of militarism by the

Nazis as an ideal led inevitably to the upsurge of successful, giant, weapon manufacturing

complexes.

And there was another factor, too, which – though designed

to put a brake on the Germans’ rearmament and to slow down their capacity to

develop new weapons – actually had the effect of greatly intensifying

development. This was the Treaty of Versailles which forbade the production of

large ships, of high-capacity aircraft, of large-calibre weapons; but the Ger

mans quickly overcame these limitations as far as they could by devoting new energies

to making effective weapons within these limits. Thus one had

convertible firearms, which could quickly be adapted for military use; one had

high-velocity guns; one saw the pocket-battleship arise and the perfection of

aircraft and gliders – all factors which, between them, enabled the Nazis

quietly to evade many of the apparently inevitable restrictions of the Treaty

of Versailles.

Factories in the industrial combines of Krupp, Mauser, and

many others supplied arms and ammunition to many countries – including, in some

cases, entire manufacturing establishments to countries as far away as South

America – and including others, such as Russia, later to become her foes.

Even before the First World War there had been an Army

Weapons Office, which had a branch known as ‘Wa Pruf’ – an abbreviation

of Heeres waffenamt Prufwesen, or Army Testing Office –

designed specifically for the testing and improvement of weapons. It was, in

essence, a proving ground and from it many important new changes and

modifications were de rived. One of the experts in this division, Carl Cranz,

later formed a section of the Wa Prdf known as Waffen Forschungs

– Wa F for short – which was specifically set up as a research and

ballistics institute in its own right. This formed the first basis for further

development in the Hitler regime; indeed when Cranz retired (aged over seventy,

according to reports) he was replaced by a Professor Schumann and it was he who

remained in charge right through to the end of the Second World War.

But here too the trend away from research for its own sake

took a toll. For theinstitute became less prestigious

and its leader found he was often left virtually out in the cold; it

was themore practical activities of Wa Pruf which seemed to

be in greatest demand. Thus it was that the munitions manufacturers who did not

wish to incur the labour and expense of establishing their own research institutes,

passed their work over to the Waffenamt – but found that the drift away from

pure research tended to deny them many of the benefits they might otherwise

have derived. So, in essence, the Ordnance did not have the research facility

they needed. When eventually things did develop in this sphere, it was almost

too late. However the practical experiences of fight ers and tacticians using

German weapons in the Spanish Civil War did provide some valuable practical

trials and experience of the weapons in practice.

In the naval field, much important introduction of new

technology was undertaken. The limits set by the Versailles treaty on warships

was 10,000 tons; but by the maximum use of light-alloy materials and the development

of high-rate are welding of a remarkably sophisticated degree of design, the

German technologists were able to overcome many of these limitations.

The research effort was largely based on the investment of consider able sums by the German business concerns who stood to make a killing by the production and sale of successful weaponry and equipment. There was an official Marine- Waffenamt (Naval testing office) under the Minis ter who acted as the Naval Commander – Oberkommando der Marine – and there were several experimental establishments (Versuchsanstalt) too. These included several organisations under the headings of Chemische-Physikana lische (Chemical and Physical Research), Torpedo, Sperr (Mines), and Nachrichen (Radio). Other facilities such as the Forschungsentwicklung Patente took care of patents and legal operations.

However in naval research too, in spite of the restrictions

of Hitler’s anti-intellectualism, the German resources were such as to

establish a world lead in technical perfection and expertise. But in the

Luftwaffe, things were somewhat different.

Here there was strong government research interest and,

rather than leave things too much to the individual activities of the business

combines, the technical competence of the government’s resources was developed

to a state of high activity and production. By shelving off the some what

arbitrary demands of the policy coordinators of the government, the German air

ministry was readily able to guard its independence of action; it would not be

intimidated by anyone, and-probably partly as a result of the haughty, almost

arrogant self-satisfaction of the army and navy research workers – it managed

to create an aura of superiority for itself. Though Ger many, for the reasons

we have already outlined, had a justified reputation as a leading producer of

artillery and naval equipment, there were many other countries with equal or

better air ministries and Germany did not have any unique position of

peerlessness in this field. But the high morale of the Luftwaffe paid off

handsomely and indeed it enabled the Germans to achieve very advanced aims

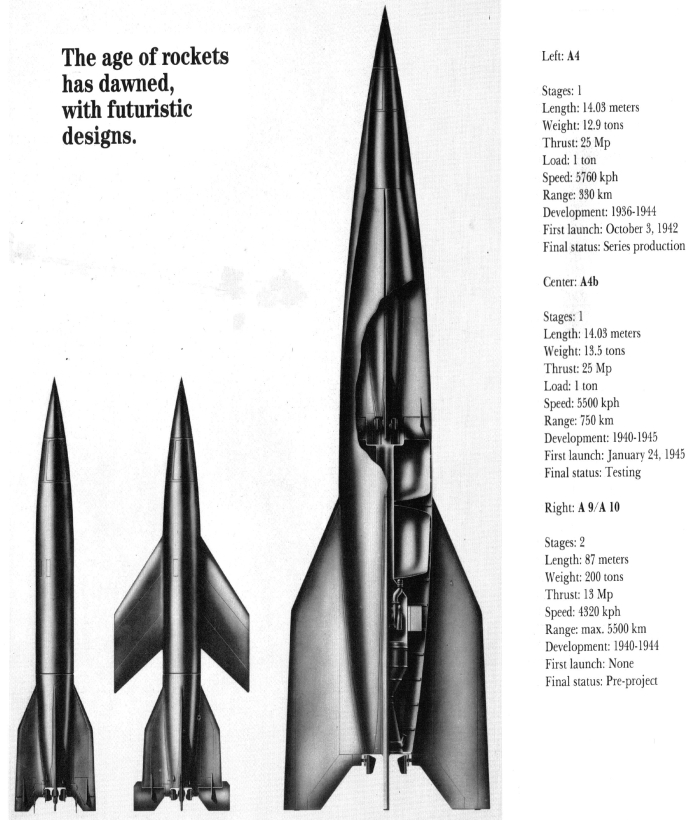

indeed. The rocketry research and development, as a case in point, was, as we

shall see, remarkable and indeed quite unique as an exercise in the application

of technology on an unprecedented scale.

It was in 1935 that Germany managed to escape from the

strictures of the Treaty of Versailles and set about the redevelopment of her

air force in a big way. Not that she came to the problem completely cold: a

secret (and quite illegal) arrangement had been under way for some years before

– exactly how many is by no means certain – by which German airmen had been

instructed and aided by the Russian air force in a reciprocal agreement. The

Chief of Staff of the Luftwaffe at about this time, General Wever, was

fanatical about the potentialities of larger and longer-range aircraft as part

of the expansionist policy of the Nazis. It must have been with great

satisfaction that Germany built and flew the first all-metal air craft of any

size at this time – the Dornier X – and many international trophies and prizes

went to German aeroplanes in the late 1930s. It is said that a record speed of

469.22 mph was reached in April 1939 by a Captain Wendel, flying a

Messerschmitt 109(R) – a speed not to be reached again until after the war’s

end, at least by air screw-propelled aircraft.

Even in this field the Germans were working secretly on a

number of projects which were later to surprise the Western world at large;

jet-propulsion was at this stage very much more highly developed than the

Allies knew, and rocket-powered aircraft were already on the drawing board. The

most terrible of all of the German secret weapons were the rockets, of course –

and these were beginning to be developed too, behind closed doors; as early as

1931 the first of the modern liquid fuelled rockets took to the air and

reached a height of perhaps 1,000 feet from a base in Dessau and within two

years secret teams were investigating the possibilities of manned rocket

flight. The quickest way of reaching the enemy is through the air, and it is

only natural that it was the Luftwaffe research establishments that were amongst

the most progressive in forging these new, surprising weapons of war.

And so whilst the military and naval specialists worked for

much of the war effort through the independent, business-backed organisations

designed to develop new – and thence marketable – weapons, the Luftwaffe research

remained close to the government. It would have been sense less to set up

governmental establishments, when there were such clear risks of duplication of

the independent laboratories, and in addition it would have been financially

difficult to tempt away the industrial research workers – who were by this time

amongst the most highly-paid technologists and designers in Europe, and

probably in the world.

But, with no traditional aircraft industry, the government

became the only real supporter of aerial research; the men were trained,

appointed, and distributed by a central machinery run by the Ministry at a

senior level; their ultimate head, Goring, was as we have seen an admirer of

brain power and what it could attain; and as the years ticked by the

developments themselves set a precedent which (though badly-organised and too

spasmodic to be effective by modern standards) had not been seen before in the

history of warfare. For its time it was incredible – and it worked.

But where were the establishments, and what were they like?

Perhaps as important, just how was the organisation arranged for this mammoth

task?

At the head of the army research was the Supreme Commander,

who – through Speer’s Ministry of Arms and War Production – controlled the

general policies of the Wa Pruf. On a par with this department stood the Waffen

Forschungs, weapons research section, which tended always to teeter on

the brink of prominence but which (probably due to poor organisation and

conflicting policy decisions as the war progressed) never came to hold the same

degree of prominence as Wa Pruf. Many students of the war years have in fact

imagined that Wa F was a sub-division of the Wa Pruf itself, but in

organisational terms the two were of equal status. Both were controlled in a

single office known asHeereswafjenamt, or Weapons Office, under the

control of General K Becker until his death early in the war years, when

General Leeb took over. And finally, working alongside the departments Wa Pruf

and Wa F, was the Beschaffung, or purchasing and production

section. This was the commercial division responsible for obtain ing tenders

for production, the buying of raw materials and the letting of production

contracts to outside firms.

Subdivisions were set up to investigate such separate

branches of research as ammunition and weapons, engineering – in the broadest

sense – signalling, optical and communications equipment, and rocketry. This

somewhat anomalous state of affairs arose because rockets were regarded (as

they still are, by some military men) as having a split personality. Some say

they are in essence artillery shells, which happen to take their cartridge

charge with them; others argue that they are really aircraft but with shorter

wings and without the pilot.

And so two divisions of the army’s Wa Pruf were set up: one

for solid -fuelled rockets, the other for liquid -fuelled. With an enthusiastic

Major General Dornberger at the head, a team of some 250 of Germany’s

best young scientists was assembled before the outbreak of the war and they were

given money, status and equipment to – simply – develop world shattering

rockets. From the pre-war site of Kummersdorf, the group moved in 1937 to

Heeresrersuchsstelle (army testing ground) Peenemunde and began work in

earnest. Later the facility was dispersed to Bliecherode and Kochel, after the

Allied forces had learned of the Peenemunde centre and begun to attack it.

Kummersdorf proving ground – situated near the capital

Berlin – was then developed purely as a proving ground for rockets and guns.

There were said to be fifteen separate test areas, but throughout the war

period the facility was not stretched to capacity. Many of Germany’s most

up-to- date and secret weapons were tested here until their every

characteristic was known and understood, and as the war went on much of this

assessment and proving analysis was carried out at a similar ground at Gottow.

Chemical warfare, which might well have provoked the most

appalling consequences of conflict ever seen in warfare, was also in the Nazis’

minds at this time. As we shall see, they spent much time and effort in the

pursuit of faster, deadlier poisons and developed, among other less sophisticated

secret materials, several potent nerve gases by the war’s end. The centre of

development and testing was at a proving ground near Raubhammer. The whole

enterprise was carefully controlled and the camouflaged buildings were often

virtually undetectable to even the closest aerial recon naissance by the

Allies.

And backing the whole set-up were the educational

establishments and colleges (the Hochschulinstituten) – over 200 of

them – and the independent companies or Firmen, on whom much

of the research depended.

The organisation in the navy was basically similar: here too

there were separate sub-divisions of the parent Ministry office, and as in the

army research, much of the effort relied on the cooperation and support of the

independent companies. The relevant head office here was the Marine

-Waffenamt (Naval Weapons Division) under Speer. The various

specialised sub-divisions were similar to those of the army and they were in

turn backed by the experimental and proof divisions. These provided a

cybernetic feed-back link to the development divisions, since teething troubles

and suggested improvements that came out of the proving tests were rapidly and

efficiently absorbed into the rationale for the following phases of development

and in this way – a form of mechanical evolution by `survival of the fittest’ –

the quality was not only maintained but steadily and consistently improved.

The organisation of the air ministry was immense. In the

very beginning of the preparation for war there was a change away from the

organisational machine of the army and navy re search in that Reichsmarschall

Goring took a prominent personal stand at the top of the tree and had overall

control of policy and development (even above the level of authority of the

Ministerium Speer). Immediately below him there was a split into two functions:

the Reich Luftfahrtminist erium, or Air Ministry proper, and the scientific and

technical branch, responsible for secret weapon development amongst other

tasks.

One of the main divisions here was the Berlin-based Technisches

Amt, the chief technical office of the Ministry itself. Initially at

the head of this important division was General Udet; he was replaced by

General Milch for the bulk of the wartime period and, later, by General

Diesing. Most of the staff of this division were, in fact, military men and

their task was basically to organise and co-ordinate research and development

of aircraft, aerial weapons, communications equipment, and the like – all of it

done under conditions of top security.

The separate specialised organisations themselves were

varied. Zelle was the division concerned with airframe

design; Motor handled the production and research into aero

plane engines of all kinds. Gerate(instrumentation) and Funk (radio-

communications and radar equipment) supplied the most up-to-date equipment for

the flying forces, and Waffen, or weapons, carried out a

prodigious amount of development into armoury of all kinds, with the exception of

bombs. This was the responsibility of the Bomben division, who also

had the assignment of developing new bomb sights and aiming equipment. Boden handled

ground-based equipment and Torpedo included the research into

mines dropped from aircraft of all kinds. The Fernsteuer Gerate embraced

the rocketry that led to the development of the V-1 flying bomb. This was

simply because, as described earlier, some of the rockets were regarded as

being ‘pilotless aircraft’ and, as such, clearly they ought to be placed under

the Air Ministry rather than those which (like the V-2) were essentially

wingless missiles. This did mean, though, that there was a fundamental division

between the two activities.

The whole operation was coordinated through the Forschung

Fuhrung (literally meaning research-guidance) division, generally

known as Fo-Fd. Its team of four scientific chiefs was always on hand for

discussions with the Berlin powers and the degree of co-ordination effected

between research and requirements was great – too great, as it turned out, for

changes of emphasis at governmental level were often rapidly transmuted into a

sudden alteration in a research programme which, whatever might be argued about

its short-term expediency, cannot have done any good at all to the progress of

the overall effort.

And finally, acting as the workhorse of the whole machine,

there were several Anstalt establishments under the

supervision of a director who controlled the several separate units in each

institute. The Fo-Fu had laid down a policy on the establishment of such

institutes, which laid stress on congenial fraternal control, good living

standards, and a dignified working environment; plenty of finance and material

backing and an opportunity for the frequent exchange of ideas on the

interdisciplinary basis so necessary for effective furtherance of high-rate

research.

The Zentralstelle fur wissenschaftliche Berichterstattung (Centre

for Scientific Records) acted as a centre for the co ordination of publications

of new discoveries. All scientists – even those working in secret fields – like

to see their work in print, and numbers of reports were produced and circulated

to personnel who were involved. A number of special yearbooks were instituted

to bring the recognition of leading scientists to the attention of their more

distant colleagues. Much was done to raise morale and efficiency – and it paid

off handsomely in many respects. So, come to that, did the positions held by

the scientists: salaries equivalent to $5,500 (£1,830) were paid annually to a

typical research-worker, and that was worth vastly more in Germany at that time

than it seems to be in today’s terms.

Let us take a look back at the kind of surroundings that

these scientists worked in – they were remarkable, even by today’s standards,

and have a distinctly James Bondian aura about them.

On the outskirts of Braunschweig lay a large area of

woodland, surrounded, in the more open countryside, by a few scattered farm

buildings. At least, that is how it appeared to aerial reconnaissance. But this

innocuous little corner of Germany was actually something quite different –

underneath the camouflage. This was the Luftfahrtforschungsanstalt

Hermann Goring, the Goring Aerial Weapon Establishment, and it was one

of the leading centres of top-secret developments. None of the central

buildings was visible from the air, as they were all below tree level and the

branches of the forest covered them completely. There were at least forty

secret weapons establishments in this one unit, most of them devoted to the improvement

of armour and the testing of ballistic projectiles. A large supersonic wind

tunnel was built, and – for topographical reasons – the air intake had to be on

open ground. So the German specialists erected a dummy farm-house to occupy the

site, complete in every detail; and on one end (where the air intakes were) was

a small out-house. Its roof slid sideways in its entirety to reveal the jet

ducts when the device was going to be in use, and then they were quietly and

unobtrusively slid back again after wards, leaving the supporting beams

standing rather conspicuously along side. But no-one ever noticed.

And so it was that this immense establishment was erected

and kept in full operation throughout the war without anyone knowing about it;

two bombs did fall near the site during the entire war, but they were errors on

bombing raids aimed at the town nearby.

At Ruit, eight miles or so from Stuttgart, another such

institute (also named after a leading aviation leader) was established,

the Luftfarht forschungsangstalt Graf Zeppelin; but this had

more of the traditional appearance of a German research centre. As such it was

soon located by Allied Intelligence, and bombed.

This institute was basically concerned with the then new

science of aerodynamics. Models of secret weapons – rockets, missiles, and so

on – were tested under extremely sophisticated conditions.

At Peenemunde an immense establishment was erected at a cost

of over $120,000,000 (£50,000,000) to house, eventually, over 2,000 scientists.

They were there to study rocketry, and particularly to build the A-series which

gave rise to the V-2 (or A-4, as it was known to the scientists). The centre

was built on an island at the mouth of the Oder, now the border between East

Germany and Poland, but at the time still in Germany itself. The island is

called Usedom and to fly over the area today, as I have recently done, demonstrates

how unlikely it was that the British reconnaissance authorities would ever show

much initial interest in the site as a centre for top-level secret

developments. It was too far out from the centre of things: too much out on the

limb. And the scattered buildings that did show up on routine pictures were

quite typical of settlements dotted all over the German countryside. But this

was where much of the most revolutionary of all the secret weapon development

was centred. At the far north of the small island were the main test area and

launching pads; along the coast lay the production plants and at the south of

this stretch were the personal quarters of the staff. Behind this area were the

barracks housing the military in the region.

Some almost routine bombing was carried out in 1943, when

much of the area was shattered; but the main guidance control systems building

– where much of the most vital research was going on – escaped undamaged. Even

so, over 800 of the people on the island were killed when the raid took place,

in the middle of August. After this, it was realised that some of the facility

had better be dispersed throughout Germany; thus the theoretical development

facility was moved to Garmisch-Partenkirchen, development went to Nordhausen

and Bleicherode, and the main wind-tunnel and ancillary equipment went down to

Kochel, some twenty-four miles south of Munich. This was christened Was

serbau Versuchsanstalt Kochelsee (experimental waterworks project) and

gave rise to the most thorough research centre for long-range rocket

development that, at the time, could have been envisaged.

They built a wind tunnel in which the air speed could be

raised to the order of 3,000 mph, far better than anything else envisaged

elsewhere in the world at that time. To many scientists the very idea of such

an air velocity would have seemed impracticable without a vast fan unit to

propel it: but the Kochel team designed instead a system which made the atmospheric

pressure do the work for them. They constructed a vast pressure vessel of

nearly 10,000 cubic feet and equipped it with a fairly powerful exhausting

pump. In this way it could be reduced to near-vacuum in a very short while. At

the moment that the test was to take place, a valve was opened admitting the

atmosphere through an experimental chamber one and a half feet across and the

model projectile inside was photographed during a whole range of air speeds, to

show exactly how it would behave; and small pressure tubes were situated all

over the models, flush with the surface, to measure the pressure changes

produced by supersonic flight. The results were not perfect in some respects

(for instance, there were problems of erosion of the chamber by the

high-velocity air-flow, and-because it was working in a partial vacuum – the

chamber was always below air pressure and this in itself introduced discrepancies

of a minor order).

The Kochel apparatus was, then, a supreme example of

advanced apparatus; yet in one respect ‘at least it suffered from a fault often

found in German war-time secret research. This was a simple lack of effort in

the field of making instruments for taking experimental readings: the pressure

tubes, for example, ran to small u- tubes filled with fluid. During a test, a

dozen or so technicians would cluster around, all taking notes feverishly and

memorising what took place. At no time, apparently, did anyone make an

automatic plotter to do the job mechanically so that the recorded results,

drawn on a roll of paper, could be examined later; indeed no-one even thought

of taking photographs of the tubes for examination and accurate interpretation

afterwards.

This failure to provide good instrumentation for

experimental work is often clear from a perusal of the reports of the time.

However this did not apply to the apparatus for the test itself, which was

always of a high quality. The shock-wave photographs at Kochel, for example,

were taken by the most sophisticated apparatus specially developed by companies

such as the Zeiss organisation.

So good were the results that the Germans envisaged an even

better tunnel, with a peak air velocity of 8,000 mph; they were going to construct

a tunnel through more than a mile of rock to an industrial reservoir several

hundreds of feet higher than the establishment itself; the water pressure, they

felt, would drive high -speed turbines and produce a positive air flow of the

order required. But this tunnel was never built before the war came to its end.

Even more grandiose in some respects was a gigantic tunnel,

twenty -five feet across, capable of working at up to the speed of sound which

was under construction at Otztal, Bavaria, when the war ended. Here too

turbines driven by falling water from a nearby source were to have been the

motive force for its operation.

Much useful work was done in ballistics at the Technische

Akademie der Luftwafe – the technical academy – under Schardin, one of

the leading ballistics experts of the time. There were altogether thirteen

institutes in the Akademie, covering subjects as diverse as

physical arid mechanical sciences, aircraft performance and control, and the

performance of engines. It also carried out much definitive work on the

functioning of explosives in shaped charges: depending on whether the charge is

flat, spherical, or concave, the effect of the blast of a given amount of

contact ex plosive can vary enormously – this is how it is that the slow,

ponderous shell of a bazooka can blast a hole through the armour of a heavy

tank.

This, then, was where the research was done. The conditions and pay were excellent, morale was high, and results were widely acclaimed. Not only that, but the deployment of this varied, vast conglomeration of facilities was intelligently done in view of the war situation, and the ingenious camouflage employed for many of them, the false buildings and sliding roofs, kept their work and even their existence a complete secret – not only to the Allies, but indeed even to the Germans themselves. Such a set-up is ideal for the furtherance of secret work, and the German secret weapon programme pressed steadily ahead as a result with incredible and in some cases devastating results.