Kievan Rus, the first organized state located on the lands

of modern Russia, Ukraine, and Belarus, was ruled by members of the Rurikid

dynasty and centered around the city of Kiev from the mid-ninth century to

1240. Its East Slav, Finn, and Balt population dwelled in territories along the

Dnieper, the Western Dvina, the Lovat-Volkhov, and the upper Volga rivers. Its

component peoples and territories were bound together by common recognition of

the Rurikid dynasty as their rulers and, after 988, by formal affiliation with

the Christian Church, headed by the metropolitan based at Kiev. Kievan Rus was

destroyed by the Mongol invasions of 1237–1240. The Kievan Rus era is

considered a formative stage in the histories of modern Ukraine and Russia.

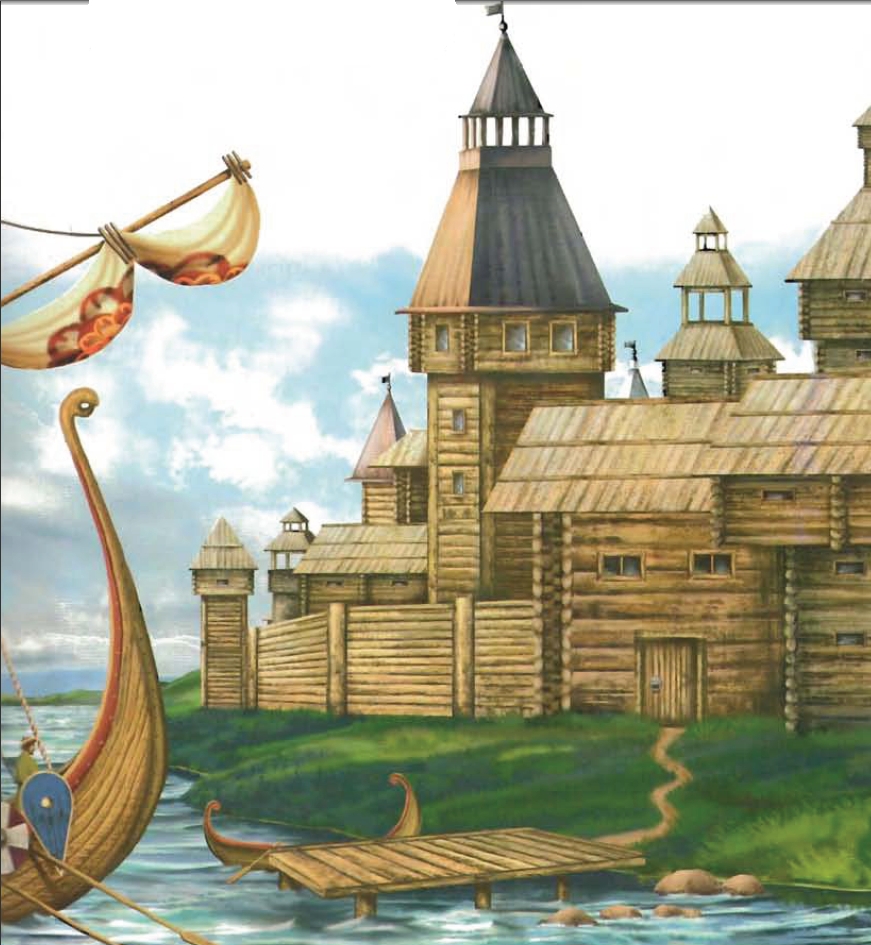

The process of the formation of the state is the subject of

the Normanist controversy. Normanists stress the role of Scandinavian Vikings as

key agents in the creation of the state. Their view builds upon archeological

evidence of Scandinavian adventurers and travelling merchants in the region of

northwestern Russia and the upper Volga from the eighth century. It also draws

upon an account in the Primary Chronicle, compiled during the eleventh and

early twelfth centuries, which reports that in 862, Slav and Finn tribes in the

vicinity of the Lovat and Volkhov rivers invited Rurik, a Varangian Rus, and

his brothers to bring order to their lands. Rurik and his descendants are

regarded as the founders of the Rurikid dynasty that ruled Kievan Rus.

Anti-Normanists discount the role of Scandinavians as founders of the state.

They argue that the term Rus refers to the Slav tribe of Polyane, which dwelled

in the region of Kiev, and that the Slavs themselves organized their own

political structure.

According to the Primary Chronicle, Rurik’s immediate

successors were Oleg (r. 879 or 882 to 912), identified as a regent for Rurik’s

son Igor (r. 912–945); Igor’s wife Olga (r. 945–c. 964), and their son

Svyatoslav (r. c. 964–972). They established their authority over Kiev and

surrounding tribes, including the Krivichi (in the region of the Valdai Hills),

the Polyane (around Kiev on the Dneper River), the Drevlyane (south of the

Pripyat River, a tributary of the Dneper), and the Vyatichi, who inhabited

lands along the Oka and Volga Rivers.

The tenth-century Rurikids not only forced tribal

populations to transfer their allegiance and their tribute payments from Bulgar

and Khazaria, but also pursued aggressive policies toward those neighboring

states. In 965 Svyatoslav launched a campaign against the Khazaria. His venture

led to the collapse of the Khazar Empire and the destabilization of the lower

Volga and the steppe, a region of grasslands south of the forests inhabited by

the Slavs. His son Vladimir (r. 980–1015), having subjugated the Radimichi

(east of the upper Dnieper River), attacked the Volga Bulgars in 985; the

agreement he subsequently reached with the Bulgars was the basis for peaceful

relations that lasted a century.

The early Rurikids also engaged their neighbors to the south

and west. In 968, Svyatoslav rescued Kiev from the Pechenegs, a nomadic, steppe

Turkic population. He devoted most of his attention, however, to establishing

control over lands on the Danube River. Forced to abandon that project by the

Byzantines, he was returning to Kiev when the Pechenegs killed him in 972.

Frontier forts constructed and military campaigns waged by Vladimir and his

sons reduced the Pecheneg threat to Kievan Rus.

Shortly after Svyatoslav’s death, his son Yaropolk became

prince of Kiev. But conflict erupted between him and his brothers. The crisis

prompted Vladimir to flee from Novgorod, the city he governed, and raise an

army in Scandinavia. Upon his return in 980, he first engaged the prince of

Polotsk, one of last non-Rurikid rulers over East Slavs. Victorious, Vladimir

married the prince’s daughter and added the prince’s military retinue to his

own army, with which he then defeated Yaropolk and seized the throne of Kiev.

Vladimir’s triumphs over his brothers, competing non-Rurikid rulers, and

neighboring powers provided him and his heirs a monopoly over political power

in the region.

Prince Vladimir also adopted Christianity for Kievan Rus.

Although Christianity, Judaism, and Islam had long been known in these lands

and Olga had personally converted to Christianity, the populace of Kievan Rus

remained pagan. When Vladimir assumed the throne, he attempted to create a

single pantheon of gods for his people, but soon abandoned that effort in favor

of Christianity. Renouncing his numerous wives and consorts, he married Anna,

the sister of the Byzantine Emperor Basil. The Patriarch of Constantinople

appointed a metropolitan to organize the see of Kiev and all Rus, and in 988,

Byzantine clergy baptized the population of Kiev in the Dnieper River.

After adopting Christianity, Vladimir apportioned his realm

among his principal sons, sending each of them to his own princely seat. A

bishop accompanied each prince. The lands ruled by Rurikid princes and subject

to the Kievan Church constituted Kievan Rus.

During the eleventh and twelfth centuries Vladimir’s

descendants developed a dynastic political structure to administer their

increasingly large and complex realm. There are, however, divergent

characterizations of the state’s political development during this period. One

view contends that Kievan Rus reached its peak during the eleventh century. The

next century witnessed a decline, marked by the emergence of powerful

autonomous principalities and warfare among their princes. Kiev lost its

central role, and Kievan Rus was disintegrating by the time of the Mongol

invasion. An alternate view emphasizes the continued vitality of the city of

Kiev and argues that Kievan Rus retained its integrity throughout the period.

Although it became an increasingly complex state containing numerous

principalities that engaged in political and economic competition, dynastic and

ecclesiastic bonds provided cohesion among them. The city of Kiev remained its

acknowledged and coveted political, economic, and ecclesiastic center.

The creation of an effective political structure proved to

be an ongoing challenge for the Rurikids. During the eleventh and twelfth

centuries, princely administration gradually replaced tribal allegiance and

authority. As early as the reign of Olga, her officials began to replace tribal

leaders. Vladimir assigned a particular region to each of his sons, to whom he

also delegated responsibility for tax collection, protection of communication

and trade routes, and for local defense and territorial expansion. Each prince

maintained and commanded his own military force, which was supported by tax

revenues, commercial fees, and booty seized in battle. He also had the

authority and the means to hire supplementary forces.

When Vladimir died in

1015, however, his sons engaged in a power struggle that ended only after four

of them had died and two others, Yaroslav and Mstislav, divided the realm

between them. When Mstislav died (1036), Yaroslav assumed full control over

Kievan Rus. Yaroslav adopted a law code known as the Russkaya Pravda, which

with amendments remained in force throughout the Kievan Rus era.

He also attempted to bring order to dynastic relations.

Before his death he issued a “Testament” in which he left Kiev to his eldest

son Izyaslav. He assigned Chernigov to his son Svyatoslav, Pereyaslavl to

Vsevolod, and lesser seats to his younger sons. He advised them all to heed

their eldest brother as they had their father. The Testament is understood by

scholars to have established a basis for the rota system of succession, which

incorporated the principles of seniority among the princes, lateral succession

through a generation, and dynastic possession of the realm of Kievan Rus. By

assigning Kiev to the senior prince, it elevated that city to a position of

centrality within the realm.

This dynastic system, by which each prince conducted

relations with his immediate neighbors, provided an effective means of

defending and expanding Kievan Rus. It also encouraged cooperation among the

princes when they faced crises. Incursions by the Polovtsy (Kipchaks, Cumans),

Turkic nomads who moved into the steppe and displaced the Pechenegs in the

second half of the eleventh century, prompted concerted action among Princes

Izyaslav, Svyatoslav, and Vsevolod in 1068. Although the Polovtsy were

victorious, they retreated after another encounter with Svyatoslav’s forces.

With the exception of one frontier skirmish in 1071, they then refrained from

attacking Rus for the next twenty years.

When the Polovtsy did renew hostilities in the 1090s, the

Rurikids were engaged in intradynastic conflicts. Their ineffective defense

allowed the Polovtsy to reach the environs of Kiev and burn the Monastery of

the Caves, founded in the mideleventh century. But after the princes resolved

their differences at a conference in 1097, their coalitions drove the Polovtsy

back into the steppe and broke up the federation of Polovtsy tribes responsible

for the aggression. These campaigns yielded comparatively peaceful relations

for the next fifty years.

As the dynasty grew larger, however, its system of

succession required revision. Confusion and recurrent controversies arose over

the definition of seniority, the standards for eligibility, and the lands subject

to lateral succession. In 1097, when the intradynastic wars became so severe

that they interfered with the defense against the Polovtsy, a princely

conference at Lyubech resolved that each principality in Kievan Rus would

become the hereditary domain of a specific branch of the dynasty. The only

exceptions were Kiev itself, which in 1113 reverted to the status of a dynastic

possession, and Novgorod, which by 1136 asserted the right to select its own

prince.

The settlement at Lyubech provided a basis for orderly

succession to the Kievan throne for the next forty years. When Svyatopolk

Izyaslavich died, his cousin Vladimir Vsevolodich Monomakh became prince of

Kiev (r. 1113–1125). He was succeeded by his sons Mstislav (r. 1125–1132) and

Yaropolk (r. 1132–1139). But the Lyubech agreement also acknowledged division

of the dynasty into distinct branches and Kievan Rus into distinct

principalities. The descendants of Svyatoslav ruled Chernigov. Galicia and

Volynia, located southwest of Kiev, acquired the status of separate

principalities in the late eleventh and twelfth centuries, respectively. During

the twelfth century, Smolensk, located north of Kiev on the upper Dnieper

river, and Rostov- Suzdal, northeast of Kiev, similarly emerged as powerful

principalities. The northwestern portion of the realm was dominated by

Novgorod, whose strength rested on its lucrative commercial relations with

Scandinavian and German merchants of the Baltic as well as on its own extensive

empire that stretched to the Ural mountains by the end of the eleventh century.

The changing political structure contributed to repeated

dynastic conflicts over succession to the Kievan throne. Some princes became

ineligible for the succession to Kiev and concentrated on developing their

increasingly autonomous realms. But the heirs of Vladimir Monomakh, who became

the princes of Volynia, Smolensk, and Rostov-Suzdal, as well as the princes of

Chernigov, became embroiled in succession disputes, often triggered by attempts

of younger members to bypass the elder generation and to reduce the number of

princes eligible for the succession.

The greatest confrontations occurred after the death of

Yaropolk Vladimirovich, who had attempted to arrange for his nephew to be his

successor and had thereby aroused objections from his own younger brother Yuri

Dolgoruky, the prince of Rostov-Suzdal. As a result of the discord among

Monomakh’s heirs, Vsevolod Olgovich of Chernigov was able to take the Kievan

throne (r. 1139–1146) and regain a place in the Kievan succession cycle for his

dynastic branch. After his death, the contest between Yuri Dolgoruky and his

nephews resumed; it persisted until 1154, when Yuri finally ascended to the

Kievan throne and restored the traditional order of succession.

An even more destructive conflict broke out after the death

in 1167 of Rostislav Mstislavich, successor to his uncle Yuri. When Mstislav

Izyaslavich, the prince of Volynia and a member of the next generation,

attempted to seize the Kievan throne, a coalition of princes opposed him. Led

by Yuri’s son Andrei Bogolyubsky, it represented the senior generation of

eligible princes, but also included the sons of the late Rostislav and the

princes of Chernigov. The conflict culminated in 1169, when Andrei’s forces

evicted Mstislav Izyaslavich from Kiev and sacked the city. Andrei’s brother

Gleb became prince of Kiev.

Prince Andrei personified the growing tensions between the

increasingly powerful principalities of Kievan Rus and the state’s center,

Kiev. As prince of Vladimir-Suzdal (Rostov-Suzdal), he concentrated on the

development of Vladimir and challenged the primacy of Kiev. Nerl Andrei used

his power and resources, however, to defend the principle of generational

seniority in the succession to Kiev. Nevertheless, after Gleb died in 1171,

Andrei’s coalition failed to secure the throne for another of his brothers. A

prince of the Chernigov line, Svyatoslav Vsevolodich (r. 1173–1194), occupied

the Kievan throne and brought dynastic peace.

By the turn of the century, eligibility for the Kievan

throne was confined to three dynastic lines: the princes of Volynia, Smolensk,

and Chernigov. Because the opponents were frequently of the same generation as

well as sons of former grand princes, dynastic traditions of succession offered

little guidance for determining which prince had seniority. By the mid-1230s,

princes of Chernigov and Smolensk were locked in a prolonged conflict that had

serious consequences. During the hostilities Kiev was sacked two more times, in

1203 and 1235. The strife revealed the divergence between the southern and

western principalities, which were deeply enmeshed in the conflicts over Kiev,

and those of the northeast, which were relatively indifferent to them.

Intradynastic conflict, compounded by the lack of cohesion among the components

of Kievan Rus, undermined the integrity of the realm. Kievan Rus was left

without effective defenses before the Mongol invasion.

When the state of Kievan Rus was forming, its populace

consisted primarily of rural agriculturalists who cultivated cereal grains as

well as peas, lentils, flax, and hemp in natural forest clearings or in those

they created by the slash-and-burn method. They supplemented these products by

fishing, hunting, and gathering fruits, berries, nuts, mushrooms, honey, and

other natural products in the forests around their villages.

Commerce, however, provided the economic foundation for

Kievan Rus. The tenth-century Rurikid princes, accompanied by their military

retinues, made annual rounds among their subjects and collected tribute. Igor

met his death in 945 during such an excursion, when he and his men attempted to

take more than the standard payment from the Drevlyane. After collecting the

tribute of fur pelts, honey, and wax, the Kievan princes loaded their goods and

captives in boats, also supplied by the local population, and made their way

down the Dnieper River to the Byzantine market of Cherson. Oleg in 907 and

Igor, less successfully, in 944 conducted military campaigns against

Constantinople. The resulting treaties allowed the Rus to trade not only at

Cherson, but also at Constantinople, where they had access to goods from

virtually every corner of the known world. From their vantage point at Kiev the

Rurikid princes controlled all traffic moving from towns to their north toward

the Black Sea and its adjacent markets.

The Dnieper River route “from the Varangians to the Greeks”

led back northward to Novgorod, which controlled commercial traffic with

traders from the Baltic Sea. From Novgorod commercial goods also were carried

eastward along the upper Volga River through the region of Rostov-Suzdal to

Bulgar. At this market center on the mid-Volga River, which formed a nexus

between the Rus and the markets of Central Asia and the Caspian Sea, the Rus

exchanged their goods for oriental silver coins or dirhams (until the early

eleventh century) and luxury goods including silks, glassware, and fine

pottery.

The establishment of Rurikid political dominance contributed

to changes in the social composition of the region. To the agricultural peasant

population were added the princes themselves, their military retainers,

servants, and slaves. The introduction of Christianity by Prince Vladimir

brought a layer of clergy to the social mix. It also transformed the cultural

face of Kievan Rus, especially in its urban centers. In Kiev Vladimir

constructed the Church of the Holy Virgin (also known as the Church of the

Tithe), built of stone and flanked by two other palatial structures. The

ensemble formed the centerpiece of “Vladimir’s city,” which was surrounded by

new fortifications. Yaroslav expanded “Vladimir’s city” by building new

fortifications that encompassed the battlefield on which he defeated the

Pechenegs in 1036. Set in the southern wall was the Golden Gate of Kiev. Within

the protected area Vladimir constructed a new complex of churches and palaces,

the most imposing of which was the masonry Cathedral of St. Sophia, which was

the church of the metropolitan and became the symbolic center of Christianity

in Kievan.

The introduction of Christianity met resistance in some

parts of Kievan Rus. In Novgorod a popular uprising took place when

representatives of the new church threw the idol of the god Perun into the

Volkhov River. But Novgorod’s landscape was also quickly altered by the

construction of wooden churches and, in the middle of the eleventh century, by

its own stone Cathedral of St. Sophia. In Chernigov Prince Mstislav constructed

the Church of the Transfiguration of Our Savior in 1035.

By agreement with the Rurikids the church became legally

responsible for a range of social practices and family affairs, including

birth, marriage, and death. Ecclesiastical courts had jurisdiction over church

personnel and were charged with enforcing Christian norms and rituals in the

larger community. Although the church received revenue from its courts, the

clergy were only partially successful in their efforts to convince the populace

to abandon pagan customs. But to the degree that they were accepted, Christian

social and cultural standards provided a common identity for the diverse tribes

comprising Kievan Rus society.

The spread of Christianity and the associated construction

projects intensified and broadened commercial relations between Kiev and

Byzantium. Kiev also attracted Byzantine artists and artisans, who designed and

decorated the early Rus churches and taught their techniques and skills to

local apprentices. Kiev correspondingly became the center of craft production

in Kievan Rus during the eleventh and twelfth centuries.

While architectural design and the decorative arts of

mosaics, frescoes, and icon painting were the most visible aspects of the

Christian cultural transformation, Kievan Rus also received chronicles, saints’

lives, sermons, and other literature from the Greeks. The outstanding literary

works from this era were the Primary Chronicle or Tale of Bygone Years,

compiled by monks of the Monastery of the Caves, and the “Sermon on Law and

Grace,” composed (c. 1050) by Metropolitan Hilarion, the first native of Kievan

Rus to head the church.

During the twelfth century, despite the emergence of

competing political centers within Kievan Rus and repeated sacks of it (1169,

1203, 1235), the city of Kiev continued to thrive economically. Its diverse

population, which is estimated to have reached between 36,000 and 50,000

persons by the end of the twelfth century, included princes, soldiers, clergy,

merchants, artisans, unskilled workers, and slaves. Its expanding handicraft

sector produced glassware, glazed pottery, jewelry, religious items, and other

goods that were exported throughout the lands of Rus. Kiev also remained a

center of foreign commerce, and increasingly reexported imported goods,

exemplified by Byzantine amphorae used as containers for oil and wine, to other

Rus towns as well.

The proliferation of political centers within Kievan Rus was

accompanied by a diffusion of the economic dynamism and increasing social complexity

that characterized Kiev. Novgorod’s economy also continued to be centered on

its trade with the Baltic region and with Bulgar. By the twelfth century

artisans in Novgorod were also engaging in new crafts, such as enameling and

fresco painting. Novgorod’s flourishing economy supported a population of

twenty to thirty thousand by the early thirteenth century. Volynia and Galicia,

Rostov- Suzdal, and Smolensk, whose princes vied politically and military for

Kiev, gained their economic vitality from their locations on trade routes. The

construction of the masonry Church of the Mother of God in Smolensk (1136–1137)

and of the Cathedral of the Dormition (1158) and the Golden Gate in Vladimir

reflected the wealth concentrated in these centers. Andrei Bogolyubsky also

constructed his own palace complex of Bogolyubovo outside Vladimir and

celebrated a victory over the Volga Bulgars in 1165 by building the Church of

the Intercession nearby on the Nerl River. In each of these principalities the

princes’ boyars, officials, and retainers were forming local, landowning

aristocracies and were also becoming consumers of luxury items produced abroad,

in Kiev, and in their own towns.

In 1223 the armies of Chingis Khan, founder of the Mongol

Empire, first reached the steppe south of Kievan Rus. At the Battle of Kalka

they defeated a combined force of Polovtsy and Rus drawn from Kiev, Chernigov,

and Volynia. The Mongols returned in 1236, when they attacked Bulgar. In

1237–1238 they mounted an offensive against Ryazan and then Vladimir-Suzdal. In

1239 they devastated the southern towns of Pereyaslavl and Chernigov, and in

1240 conquered Kiev.

The state of Kievan Rus is considered to have collapsed with

the fall of Kiev. But the Mongols went on to subordinate Galicia and Volynia

before invading both Hungary and Poland. In the aftermath of their conquest,

the invaders settled in the vicinity of the lower Volga River, forming the

portion of the Mongol Empire commonly known as the Golden Horde. Surviving

Rurikid princes made their way to the horde to pay homage to the Mongol khan.

With the exception of Prince Michael of Chernigov, who was executed, the khan

confirmed each of the princes as the ruler in his respective principality. He

thus confirmed the disintegration of Kievan Rus.

BIBLIOGRAPHY

Chronicle of Novgorod, 1016–1471, tr. Robert Michell

and Nevill Forbes. (1914). London: Royal Historical Society.

Dimnik, Martin. (1994). The Dynasty of Chernigov 1054–1146.

Toronto: Pontifical Institute of Mediaeval Studies.

Fennell, John. (1983). The Crisis of Medieval Russia 1200–1304.

London: Longman.

Franklin, Simon, and Shepard, Jonathan. (1996). The Emergence

of Rus 750–1200. London: Longman.

Kaiser, Daniel H. (1980) The Growth of Law in Medieval Russia.

Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Martin, Janet. (1995). Medieval Russia 980–1584. Cambridge,

UK: Cambridge University Press.

Poppe, Andrzej. (1982). The Rise of Christian Russia. London:

Variorum Reprints.

The Russian Primary Chronicle, Laurentian Text, tr.

Samuel Hazzard Cross and Olgerd P. Sherbowitz-Wetzor. (1953). Cambridge, MA:

Medieval Academy of America.

Shchapov, Yaroslav Nikolaevich. (1993). State and Church in

Early Russia, Tenth–Thirteenth Centuries. NewRochelle, NY: Aristide

D. Caratzas.

Vernadsky, George. (1948). Kievan Russia. New Haven, CT:

Yale University Press.