On 9 September 1914 Chancellor Bethmann Hollweg announced Germany’s ‘September Programme’ of war aims. Whether this statement of territorial demands and military and economic ambitions was a triumphant response to early victories, or a pragmatic recognition that the war would not be short, and that the German people had to be made aware of what they were fighting for in a lengthy life-or-death struggle, the pre-emptive formulation of war aims was and remains controversial.

Although couched in defensive terminology, Germany’s war aims were expansionistic. Territorial annexations, economic domination and military control would provide, Bethmann Hollweg promised, ‘security for the German Reich in west and east for all imaginable time’. As such, Germany’s war aims were an expression of the social-Darwinist philosophy of imperialistic competition which had underpinned pre-war arms races and colonial rivalries. Weltpolitik may have failed in peacetime, but war presented an opportunity to achieve Germany’s global ambitions.

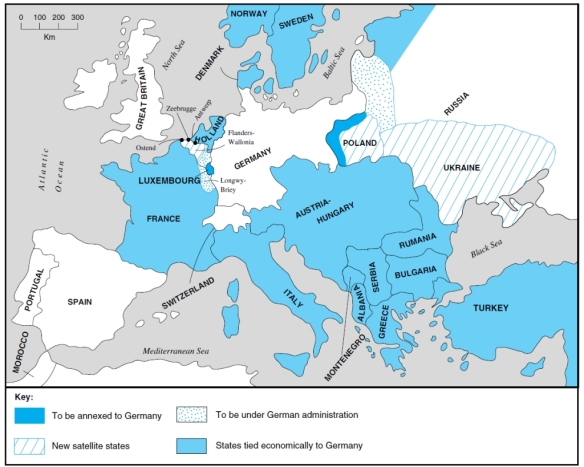

In Europe Germany wished to impose her hegemony, through a combination of territorial expansion and economic control. In the east Russian territory in Poland and the Baltic would be annexed. Subsequently, in a concession to national self-determination, it was proposed that dependent satellite states should be set up in Poland and the Ukraine at Russia’s expense. In the west Luxembourg and important economic regions of France and Belgium – the Longwy-Briey iron-ore field and the Belgian Channel ports, Antwerp, Zeebrugge and Ostend – would be incorporated within the German empire to boost Germany’s economic capacity and secure her against future British and French hostility. France, Belgium and the Netherlands would be incorporated in a German-dominated economic union – Mitteleuropa – which would stretch from the Atlantic coast in the west to Poland in the east, and from Scandinavia in the north to Turkey in the south. Africa would become a German-dominated continent. French, Belgian and Portuguese colonies in central and southern Africa would be incorporated into a central Africa economic region – Mittelafrika – which would supply German industry with raw materials. Control of the Atlantic and Red Sea coasts would secure German command of key international routes, a check on British power. With Germany’s economic interests assured, Britain’s economic and commercial hegemony could be effectively challenged.

War aims were not fixed, but evolved in response to changes in the diplomatic and military situation. Consequently the detail of German ambitions changed as the war went on, although her stated war aims remained true to the principles of 1914: ensuring German economic and strategic security and weakening Britain’s commercial superiority. By 1916 she was prepared to compromise her more extreme demands in an attempt to split the Entente and secure a separate peace with France, Russia or Belgium, which would enable her to focus on her main enemy, Great Britain. Yet Germany’s success on the battlefield – everywhere her armies fought on foreign territory – precluded the sort of concessions that would have been needed for a compromise peace. As war went on German domestic politics polarised around the issue of war aims. The political peace (burgfrieden) which the left and right had agreed on the outbreak of war finally collapsed in 1917. In July the Social Democratic and Centre parties supported a ‘peace resolution’ in the German parliament (Reichstag) which called for a negotiated peace ‘without annexations and indemnities’, as advocated by the Socialist International. The response of the right, the foundation of the nationalist German Fatherland Party (Deutsche Vaterlandspartei) committed to opposing ‘the all-devouring tyranny of Anglo-Americanism’, staked the future of the Imperial regime on a victorious peace.

The punitive peace imposed on Russia at Brest-Litovsk in March 1918 showed the world what German victory would mean in practice. The simultaneous ‘Peace Offensive’ on the western front, was to be the last gasp of Germany’s ruling military elite, who hoped that victory would stave off the growing social unrest on the home front. The allies, aware of what a German victory would mean for their sovereignty and power, fought back ferociously and turned the tables on the German army. Germany’s request for an armistice, on 4 October 1918, marked the end of an era. Beforehand the military had handed political power to liberal and socialist politicians who favoured President Wilson’s ‘Fourteen Points’ as a basis for peace (see Map 24). By the terms of the 1919 Treaty of Versailles it was to be Germany which suffered territorial annexations, economic subordination and military emasculation. In the terms of that treaty lay the roots of another conflict.

In the 1960s the historian Fritz Fischer famously argued that Germany’s September Programme of war aims represented the climax of a conscious policy of German expansionism which had its roots in the Weltpolitik of the pre-war years; that Germany had sought war as a means to assert her world power. This controversial thesis has been much debated by historians, and consensus has yet to be reached. It has subsequently been argued, for example by Volker Berghahn, that German Weltpolitik had proved a costly failure by 1914. It was not planned aggression, but fear and insecurity, which motivated Germany. Only through a formal consolidation of her power in Europe, and recognition of her global influence, could she hope to secure her future as a Great Power. Paradoxically, in pursuing such an imperialist agenda uncompromisingly she turned the rest of the world against her and brought about her own defeat and humiliation.