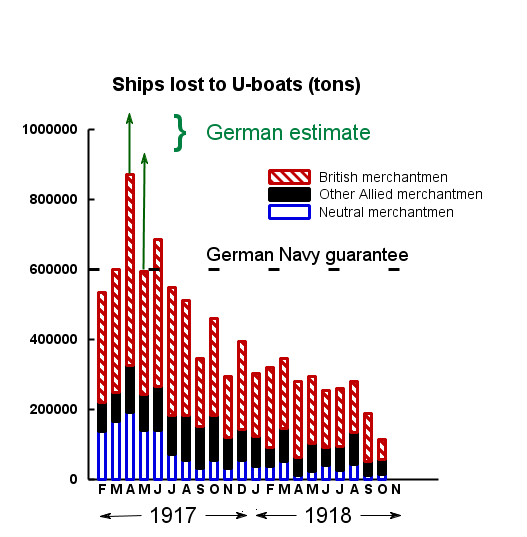

Tons of British and neutral shipping lost in 1917 and 1918, showing failure of unrestricted U-boat warfare.

One more countermeasure had not been adopted, the convoying of ships. Convoy (the grouping of merchant ships under the protection of warships) was a very old means of protecting ships and their cargoes; during the Middle Ages wine ships had crossed the Channel from Bordeaux to England in convoy, and it had been the standard method of commerce protection in the Napoleonic Wars. But the Admiralty persisted in using incorrect statistics to ‘prove’ that convoy could not work because there were not enough escorts. Only French insistence forced the British to convoy colliers taking coal to France from February 1917. In April that year, at the worst moment of the Uboat campaign, the collier convoys were suffering 0.19 per cent losses, as against 25 per cent everywhere else. This was proof enough for the influential officers in the Trade Division to lobby for the general adoption of convoy. The Admiralty fought back with all the conviction of the truly bigoted, and it seemed that the war would be lost before a decision could be made.

The argument over who can take the credit for introducing convoy is hard to resolve. The Prime Minister, Lloyd George, was only too happy to claim it, but it was almost certainly urged on him by the Cabinet Secretary, Maurice Hankey, who had already been won over by the Trade Division. With all the cunning at his command Hankey persuaded Lloyd George to overrule the Admiralty Board, and amid dire warnings of disaster the first ocean convoy sailed at the end of April. To everyone’s amazement the loss rate fell from 25 per cent to 0.24 per cent at the end of May. By November 84,000 passages had been made in convoy, and only 257 ships had been sunk.

For the U-boats it was the end of easy pickings. Smoke on the horizon now portended the arrival of a formation of ships escorted by destroyers and patrol vessels and even airships. All U-boat commanders’ reminiscences harp on the fact that targets disappeared, and gun attacks on the surface were no longer safe. Each submarine had only one shot at the convoy, reducing its chances of hitting anything, and that shot would bring immediate retaliation with depth charges or bombs.

Later in the year it was at last possible to take the offensive against the U-boats. A new horned mine, modelled on the German one, was now available in large numbers, and nightly minelaying runs into enemy waters blocked exit routes from the U-boat bases. Cryptanalysis enabled U-boats to be ambushed, hydrophones could detect submerged targets, and the depth charge enabled them to be attacked below the surface.

When the war ended in November 1918 the German Navy was forced to surrender all sea-going U-boats in Allied ports. Some 360 had been built, and 400 more lay incomplete or had been cancelled as the German war economy collapsed under the competing demands of the Army. They had sunk 11,176,550 tonnes (more than 11 million tons) of shipping and damaged 7,620,375 tonnes (7.5 million tons) more, but the cost was the loss of 178 U-boats and 5364 officers and ratings, nearly 40 per cent of the total.