By 21 May the spearhead of the German military offensive in north-western France had reached the English Channel near to the port of Abbéville, closing an armoured noose around the men of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) who found themselves trapped in a narrow salient between the French port of Boulogne and Ostende on the Belgian coast with no prospect of escape except by sea. Vice-Admiral Sir Bertram Ramsay, the hard-bitten flag officer on the Dover station, was handed the Herculean task of organising this evacuation by the Admiralty and a more inspired choice could hardly have been made. His inspirational performance in this role was matched by the heroism of those who took orders from him over the course of the next fortnight as an armada of boats ranging from the large to the ridiculously small was assembled and conveyed across the Channel to pick up the survivors of the Wehrmacht’s attack on the West.

Typical of the entire enterprise, the evacuation began on a stirring note with Anglo-French sorties at both Boulogne and Calais which helped to delay the German advance and enabled the rest of the BEF to retreat to the final Allied defensive perimeter line at Dunkerque (Dunkirk). With disaster looming for the BEF, Hitler controversially called a temporary halt to the German advance when the vanguard of his Panzer divisions was less than twenty kilometres away from the Allied troops. Taking the initiative from the armoured corps and handing it to the Luftwaffe was a colossal mistake and provided the British with an unlikely way out of the military mess they were in.

Captain William G. Tennant, Ramsay’s man on the spot in France, knew that evacuating the BEF would be a race against time. Apart from using their shallow draught vessels for lifting troops off the sandy beaches to the south and north of the town, the Allies had to get as many destroyers and other larger vessels as possible into the outer basin of the harbour to rescue the maximum number of troops in the least amount of time. In this he was aided by the individualistic nature of the Dunkirk port. It had two wooden breakwaters (moles) that jutted out into the open sea for nearly a mile (1.61km). These had been constructed to provide a more sheltered anchorage in peacetime for all the ships using the harbour and its docks. Although the West Mole leading from the burning oil terminal was obscured by smoke and flames and could not be used as a berthing stage, the East Mole stretching from the town out to sea didn’t suffer from these disadvantages. While not being designed for this purpose, it could still be used by the larger ships at Tennant’s disposal (destroyers, personnel carriers and hospital ships) as a temporary quayside if skill and ingenuity were applied to the task in hand and if the entire enterprise was graced with more than its fair share of fine weather and good luck. Unfortunately, a tricky embarkation was the least of the Admiralty’s worries since a successful homeward passage across the English Channel in the face of determined German shore-based artillery, dive-bombers and prowling U-boats could hardly be said to be a foregone conclusion. Maybe it was too much to expect but, staggeringly (some would say miraculously), all the essential ingredients for a successful evacuation held over the course of the following eight days to afford the Allies a rare psychological victory in the midst of a substantial military defeat.

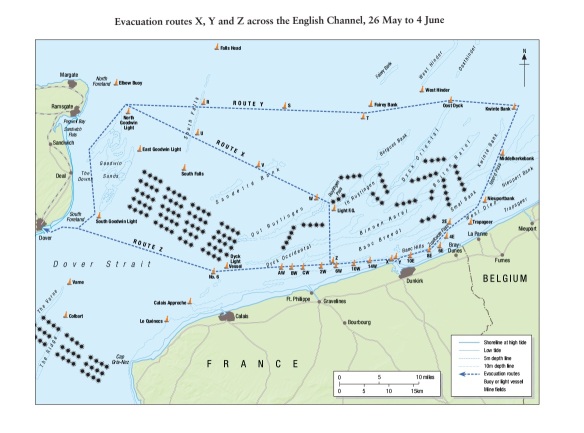

Operation Dynamo was finally given Admiralty approval at 1900 hours on 26 May and was launched on the following day with only a fairly limited expectation of success. It began modestly and far from efficiently and achieved a commensurate level of success – a mere 7,669 evacuees being plucked off the sandy beaches on 27 May. While it was better than nothing, there was general agreement that there were grounds for improvement. Apart from anything else, more and larger ships were required and greater coordination was needed at every stage of the evacuation process. As space on board the evacuation vessels was at an absolute premium, it was accepted from the outset that all the supplies of the BEF would have to be left behind to free up room for the carrying of more troops back across the Channel. Despite the frenzied efforts of enemy dive-bombers, MTBs and U-boats to disrupt the rescue mission, the numbers of BEF troops getting away from the chaos of Dunkirk ballooned over the next few days from 17,804 on 28 May to 47,310 on the following day. Although the prospect of high attritional losses and damage had been anticipated beforehand, the effect of the mayhem caused by the Germans as they redoubled their efforts to bring Dynamo to a soggy end still left the Admiralty reeling. Ramsay was hard pressed to persuade an initially reluctant Pound to continue authorising the use of their most modern destroyers for this operation. After 53,823 troops got away from the East Mole and the northern beaches on day four (30 May), the record haul of 68,014 evacuees was reached on the following day. On the anniversary of the `Glorious First of June’ 64,429 troops somehow managed to embark successfully on the vessels sent in for them even though they had to do so under a hail of bombs and strafing, and through the swirling smoke and shrieking din that accompanied an almost incessant series of air attacks. It was a tough day with such significant losses for the Allies that the Admiralty and Ramsay agreed on the need to suspend daylight operations. By then it was clear to the leading members of Ramsay’s entourage that the game was nearly up; the German Panzers were closing in on the Allied defensive perimeter around Dunkirk and it wouldn’t be long before the beaches themselves would come within enemy artillery range.

Before the ring finally closed around Dunkirk, however, a vast assortment of small craft joined their larger brethren in negotiating the Channel crossing during the late afternoon and early evening of 2 and 3 June in order to resume the evacuation exercise in heroic defiance of everything that the Germans could throw at them. Only six hours after the last of the 848 ships involved in Dynamo, HMS Shikari, pushed off from the East Mole at 0340 hours on 4 June the town of Dunkirk finally fell to forward units of the 18th German Army trapping 40,000 French soldiers within the breached perimeter. Amazingly, the surviving members of the BEF, along with a host of French troops together numbering 338,226, had been spirited away from the town and its beaches in eight days of evacuation. This was the upside of Dynamo; the downside was the total loss of seventy-two ships, including the flotilla leader Keith and eight destroyers, and virtually all the equipment, supplies and stores of the BEF. This scale of loss was significant in its own right, but the overall logistical impact was worsened by the fact that many more vessels were damaged than had actually been sunk and the worst affected ones would have to be withdrawn from active service until their repairs had been completed.

As a propaganda tool, however, Dynamo could still be trumpeted by the Allied leadership not only as an outstanding operational feat carried out under extreme duress, but also as a miraculous delivery staged literally at the last moment and from under the noses of the enemy. One senses that many on the Allied side found the idea that chance and coincidence alone were at work in this operation as being far too preposterous to contemplate. For those with faith, therefore, the successful nature of this entire episode was interpreted as a clear sign of God’s active intervention against Nazi Germany. For Winston Churchill, who had replaced Neville Chamberlain as British prime minister on 10 May, Dynamo was a psychological boost – the feel good factor was immense – and the safe return of so many troops who could be re-employed in the Allied cause again in the future was also crucially important.