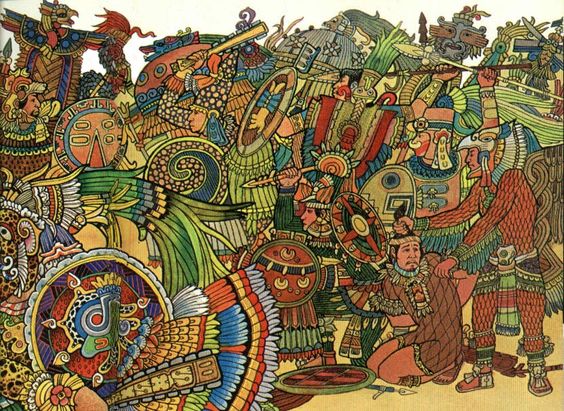

From Sahagun’s Codex Florentino it is apparent that tequihuahqueh, Otontin, and `Shorn Ones’ alike were armed, equipped and fed at the expense of the state, and other sources indicate that they lived in warrior `houses’ (tequihuacacalli) – communal lodgings equivalent to barracks – in the palace precinct. The same is also true of the religious warrior-societies known as the Eagle Warriors (Quaquauhtin) and Jaguar Warriors (Ocelomeh), occasionally referred to collectively as Quauhtlocelotl or Eagle-Jaguars. These comprised `a caste of initiates fighting for the attainment of spirituality’. Only tequihuahqueh (i. e. warriors who had taken four or more captives) could enter either of these orders, but details of any other selective process that may have been involved are not known. Certainly not every tequihuah automatically became a member, despite the Codex Mendoza’s attribution of a jaguar warsuit to all men who took four prisoners, and some additional qualification may have been required to become an Eagle Warrior in particular. Certainly pictorial evidence indicates that Eagle Warriors were considerably less numerous than Jaguars, and significantly most of the surviving pictures depicting eagle war-suits show them being worn by rulers or chieftains. Significantly too, the surviving tribute lists do not include a single picture of or allusion to an eagle war-suit, so clearly the demand must have been on a very small scale indeed, compared to an annual requirement of close to 30 jaguar war-suits.

The majority of those who did gain admission to either society were members of the nobility, and even where commoners of equal military expertise were admitted they were held in less regard than the noble elements. They even appear to have lived in their own distinct `house’ whereas the noble members were accommodated in `eagle houses’ (quauhcalli), though both alike were within the palace precinct. Joseph de Acosta (1588) records that `every order of these knights had his lodging in the palace, marked with their emblems. The first was called the Princes’ Lodging, the second of Eagles, the third of Lions and Tigers [i. e. Jaguars], and the fourth of grey knights [Acosta’s name for the Otontin]. The other common officers were lodged below in meaner houses. If anyone lodged out of his station, he suffered death.’

When they became too old to fight, Jaguar and Eagle Warriors were known as Quauheuhueh (`Eagle Elders’), and it is apparent from Duran’s work that they continued to perform important duties on campaign – such as keeping the men in order on the march, marshalling them into formation on the battlefield, and taking charge of the army’s camps – but they no longer wore their eagle or jaguar war-suits or carried arms; Duran mentions that they simply `carried staffs in their hands and wore headbands, long shell ear-plugs and labrets.’

The Quachicqueh and Otontin were considered the most courageous of all Aztec warriors and were greatly feared by their enemies, the sources referring to them fighting like madmen in battle without regard for their own safety. Duran records that each `Shorn One’ swore never to flee `even if faced by 20 enemies, nor take one step backward’, and that each Otomitl `made a vow not to retreat even if faced by 10 or 12 enemies, but rather to die.’ Unsurprisingly, therefore, they suffered grievous losses in any Aztec defeat, such as against the Tarascans in 1478/9, where they must have been virtually if not actually wiped out (only 200 of the army’s Tenochtitlan contingent reputedly survived). Sahagun noted that the `Shorn Ones’ were also described as momiccatlcani, meaning `they who hurl themselves to death’, a name comparable to the warrior-society of `crazy dogs wishing to die’ of the North American Crow Indians, who sought death in battle by their own boldness, just as Sahagun elsewhere says that the `Shorn Ones’ did. Indeed, there are enough similarities between the little that we know of the Otontin and Quachicqueh on the one hand and such Plains Indian `contrary’ warrior-societies on the other to demonstrate that ultimately both probably shared the same cultural origin.

Torquemada describes the `Shorn Ones’ as behaving like fools or crazy people on the battlefield, and Sahagun likens their comportment to that of buffoons, observing that they dressed clumsily and, elsewhere, that they were vain and outspoken, all of which denotes such self-confidence in their martial abilities that they could not be belittled by either detrimental appearance or unsociable conduct. Going back to the parallels with Plains Indians, it is also interesting to note that `Shorn Ones’ appear to have often been held back as a reserve or placed in the rearguard, which tallies with the customary behaviour of a Cheyenne `contrary’ group, the `Bowstring Society’, who took no part in battles where victory was inevitable but only attacked when the tide had turned against them. Most of the time, however, the Quachicqueh and Otontin (in that order) were in the forefront of battle, and, as already noted, they might even be temporarily interspersed among inexperienced warriors, a role in which Jaguar and Eagle warriors were also employed. (This practice originated during a campaign against Metztitlan in 1481 when, seeing the morale of his recruits badly shaken by the ferocity of the Metzoteca attack, an Aztec commander recommended that `one or two or three’ veterans should be placed among each troop of them `to give them strength and spirit’. This enabled the Aztecs to drive back the next attack and get themselves safely away from the battlefield.)

The existence of all of these elite groups may lay behind the claims made by some 16th century writers that the Aztec Speaker maintained a sizeable bodyguard. Francisco Lopez de Gomara provides one of the clearest references to this body, stating that `Moctezuma [II] had daily a company of 600 gentlemen and lords to act as his bodyguard, each with three or four armed servants to wait on him, some even with as many as 20 or more, according to their rank and wealth; so altogether they numbered 3,000 in the palace guard, some say many more’. He concedes himself, however, that `they put on this guard and show of power’ to impress the Spaniards `and that ordinarily it was smaller.’ Certainly Duran records that the Quachicqueh and Otontin in an army of Moctezuma I’s time totalled only about 2,000 men, even though these had been assembled not just from Tenochtitlan but `from all the provinces’.

Although modern authorities generally dismiss the idea of a formal bodyguard it is worth noting that Fernando de Alva Ixtlilxochitl, nephew of the last ruler of Texcoco (who one would therefore expect to be well-informed in such matters), reported the existence of warriors and captains whose special responsibility was to guard the Speaker and his family, while the conquistador Bernal Diaz del Castillo refers to Moctezuma II having `over 200 of the nobility in his guard, in other rooms close to his own’. Duran too, quoting from a lost Aztec chronicle, specifically mentions guardsmen in at least two passages – surrounding the Tlatoani Axayacatl in battle against the Matlatzinca in 1478, and accompanying Ahuitzotl (1486-1503) during a religious ceremony – in the second instance providing a reasonably detailed description of them which is worth quoting in full, wherein he calls them `gallant soldiers, every one of them of noble blood. All of these carried a staff in their hands, but no other weapons. On their heads they wore their symbols of rank as knights; these consisted of two or three green or blue feathers tied to their hair with red ribbons. Some wore the feathers erect on their heads while others wore them hanging. On their backs hung as many round tassels as the number of great deeds they had performed in battle. These tassels were attached to the feathered headbands. All these warriors wore splendid jewellery.’

Certainly a complete absence of bodyguards of any description seems highly unlikely, even in an orderly theocracy like the Aztec empire. If they were indeed provided by any of the elite warriors mentioned above we do not know which, though the Eagles and Jaguars seem the most likely candidates.