In the second week of August the Luftwaffe launched Phase 2-Adlerangriff, or Eagle Attack-the aim of which was to destroy Fighter Command on the ground and in the air. Massed bomber raids in daylight, with a strong fighter escort, would be used to cause maximum destruction.

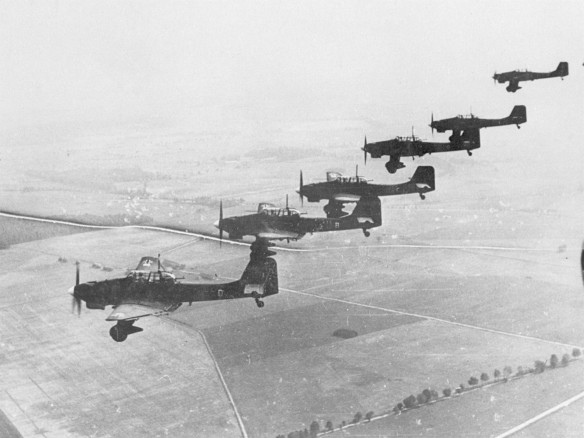

The basic bomber element was the Kette of three aircraft in V formation, with the wingmen stepped back from the leader and slightly higher or lower depending on the visibility from the cockpit, which varied with type. When flying in Staffel strength, either all Ketten flew in line astern (the Staffelkolonne) or the Staffelwinkel was adopted, in which all nine aircraft took up a large V formation.

In Gruppe strength, variations were possible. Widely used in the summer of 1940 was the Gruppenkolonne aus Staffelwinkeln, in which the three Staffelwinkeln flew in line astern. The Stab, usually a single Kette, flew at the front. The Gruppenkolonne aus geschlossenen Staffelkeilen was a valid alternative, in which each Kette in each Staffel flew in V formation, with the Ketten also in a V formation. Less often seen were the Gruppenkeil, consisting of Staffelkolonnen stepped to left and right of the leading formation, or any form of echelon by Staffeln.

When engaged by anti-aircraft fire, the formations opened out to present a more diffuse target, and began the ‘Flak Waltz’, a weave designed to ensure that the bombers were not there when the shells arrived. This could not be done on the bombing run as it spoiled the aim; at this point the bombers had to grin and bear it. When attacked by fighters, the opposite was true: formations closed as tightly as possible in order to mass their defensive fire. As previously mentioned, defensive armament was inadequate.

During the convoy battles Luftwaffe Intelligence had noted the fact that RAF fighters had a disconcerting habit of arriving promptly at the scene of the action. Monitoring British radio transmissions, they drew the obvious conclusion that the British had a sophisticated detection and control system and that the 100m towers along the coast were an integral part of this. Given that RAF fighters took twenty minutes to reach operational altitude, if the early warning system could be taken out Fighter Command would be immediately disadvantaged and the bombers would be storming in towards the coast before the alarm could be given.

Even at this early stage, the limitations of the Ju 87 had been recognised, and it was expected to be replaced by the Bf 210 fighter-bomber, or Jabo. To this end, an experimental unit, Erprobungsgruppe 210, had been formed a few weeks earlier to develop tactics. Commanded by Swiss-born Walter Rubensdorffer, it consisted of two Staffeln of Bf 110s and one of Bf 109s, the latter to provide fighter escort after dropping its bombs. Having cut its teeth on shipping attacks, it was tasked to hit the radar stations at Dover, Rye, Pevensey and Dunkirk (the last a little way inland in Kent) on 12 August.

The Jabos streaked down in shallow diving attacks and planted their bombs. The huge towers were seen to sway, but none was destroyed. However, all except Dover were off the air for several hours, although rapid repairs put the other three back on line during the afternoon. EprGr 210 suffered no losses.

Towards noon a huge raid-almost 100 Ju 88s of KG 51, with a massive fighter escort-approached the Hampshire/Sussex coast. Most of the aircraft attacked Portsmouth, but two Staffeln split off and made a steep diving attack on the radar station at Ventnor on the Isle of Wight. This time damage was severe, and Ventnor radar was out of action for weeks. KG 51 lost ten aircraft, eight to fighters, including their Kommodore, Dr Fisser, and another three damaged.

Another intelligence failure now occurred. Monitoring soon revealed that Pevensey, Rye and Dunkirk were back on the air, while transmissions apparently from Ventnor were also picked up. The RAF rushed a mobile station to the Isle of Wight, and while this only partially plugged the gap in the radar cover, to the Luftwaffe signals organisation it appeared that Ventnor was still fully functional. The conclusion was that the radar sites were almost impossible to knock out for any appreciable length of time, and further attacks on them became sporadic.

August 12 also saw the initial attacks on RAF airfields. Hawkinge and Manston were both forward airfields on the coast. At the latter, EprGr 210 was once more to the fore, backed by Dorniers from KG 2. The raid was not very effective: only one aircraft was destroyed on the ground, and Manston was operational again within twenty-four hours.

The main airfield assault, launched over the next few days, was a fiasco thanks to wrong targeting. On 13 August Johannes Fink led 74 Dorniers of KG 2 against the naval base at Sheerness and the Coastal Command airfield at Eastchurch. By complete coincidence, Spitfires of two squadrons were present on the ground, and KG 2 claimed ten destroyed, although the true figure was one. The cost was high-five Dorniers lost and five more damaged.

In mid-afternoon, a multi-pronged raid was launched. About 40 Ju 88s of KG 54 set off for Odiham and Farnborough, neither of them fighter airfields. A combination of clouds and fighter harassment ensured that their targets were not reached. About 80 Ju 88s of LG 1, with III/LG 1 led by future Ritterkreuz and Eichenlaub winner Ernst Bormann, headed for Southampton, where they caused heavy damage to the docks but, unbelievably, missed the vital Spitfire factory at Woolston. Two Staffeln broke away and headed for the fighter airfield at Middle Wallop. They failed to find it and bombed Andover instead, another non-fighter airfield.

Further west were 27 Stukas of II/StG 2 led by Ritterkreuz holder Walter Enneccerus, followed by 52 Stukas of StG 77 led by another Ritterkreuz holder, Graf von Schönborn-Wiesentheid. II/StG 2 headed for Middle Wallop but was roughly handled by Spitfires, one Staffel losing six out of nine Stukas. StG 77 failed to find the fighter airfield at Warmwell and dropped bombs at random over Dorset. Further to the east, II/StG 1 failed to find Rochester and scattered its bombs across half of Kent, while IV(St)/LG 1 attacked Detling, causing much damage. Again, neither was a fighter airfield.

The price of this catalogue of errors was high: five Do 17s, one He 111, five Ju 88s and six Ju 87s failed to return, while many more sustained severe damage. The escort fighters also suffered, eight Bf 110s and five Bf 109s being lost. By contrast, thirteen RAF fighters were lost, including the one on the ground at Eastchurch. The fabled Teutonic efficiency had been found sadly wanting.

Attacks on the following day were of lesser intensity. Manston was raided by EprGr 210, which lost two Bf 110s to ground fire in the process. Further west, three Heinkels of Stab/KG 55 raided Middle Wallop but lost their Kommodore, Ritterkreuz holder Alois Stoeckl, to defending Spitfires.

A series of heavy raids was scheduled for 15 August. In the late morning more than 40 Stukas from IV(St)/LG 1 and II/StG 1 raided the forward airfields at Hawkinge and Lympne. While they caused serious damage, no fighters had been caught on the ground. Meanwhile Luftflotte 5, based in Scandinavia, entered the battle for the first (and last) time. German Intelligence, misled by the exaggerated victory claims of Luftwaffe fighter pilots, had concluded that almost all RAF fighters were now concentrated in the south, leaving the north of England vulnerable. More than 60 Heinkels of KG 26 set out from Stavanger to attack targets in the Newcastle area. They were escorted by the Bf 110s of 1/ZG 76. Further south, about 50 unescorted Ju 88s from KG 30 took off from Aalborg and headed for the bomber base at Driffield.

KG 26 was intercepted by elements of several fighter squadrons in quick succession. The Bf 110s were unable to protect the bombers and lost seven of their number. Eight Heinkels were shot down, and with most bombs jettisoned into the sea the raid was a total failure. KG 30 achieved surprise at Driffield, plummeting from the sky to destroy ten Whitley bombers and damaging the station buildings. RAF bomber ace Leonard Cheshire, who was present at the time, called it a fine achievement. Be that as it may, it was too costly to be repeated. Seven Ju 88s were lost, all to fighters, while three more crash-landed on the continent with battle damage. No British fighters were lost in either action.

In the south, the main attack was launched in the early afternoon. EprGr 210 raided the fighter airfield at Martlesham Heath, putting it out of action for forty-eight hours but again failing to catch any fighters on the ground. Meanwhile the Dorniers of KG 3, led by Wolfgang von Chamier-Glisczinski, thundered in over the Kent coast. I and II Gruppen attacked Rochester, badly damaging the Short Brothers aircraft factory and the Pobjoy engine works. At the former, deliveries of the Stirling heavy bomber were significantly delayed, but, again, this was no part of the plan to reduce Fighter Command. III Gruppe once again turned its attention to Eastchurch. Two Dorniers were lost to fighters and another six damaged, this light rate of loss being due to the presence of a strong escort.

Further west, about 60 Ju 88s of I and II/LG 1 set out for Middle Wallop and Worthy Down (the latter again not a fighter airfield) with a strong Bf 110 escort. Little damage was caused at either, while Odiham, about 30km to the north-east, was attacked in error. Intercepted, the Germans lost eight Ju 88s, five of them from Joachim Helbig’s 4th Staffel. Helbig himself barely escaped: he owed his survival to his gunner, who directed evasive action. His aircraft took 130 hits but still flew.

The final large raid took place in the early evening, when a force of Dorniers headed for Biggin Hill and EprGr 210 went for Kenley. This time the Luftwaffe had its priorities right: both were Fighter Command sector stations. However, once again it all went pear-shaped. Harassed by fighters, the Dorniers bombed West Mailing, which was not yet operational, while Rubensdorffer led his Gruppe against Croydon. This was fatal in more ways than one: first, Croydon was within the prohibited Greater London area; secondly, the unit was intercepted over the target and suffered horrific casualties. Seven of the fifteen Bf 110s were shot down, including Rubensdorffer’s.