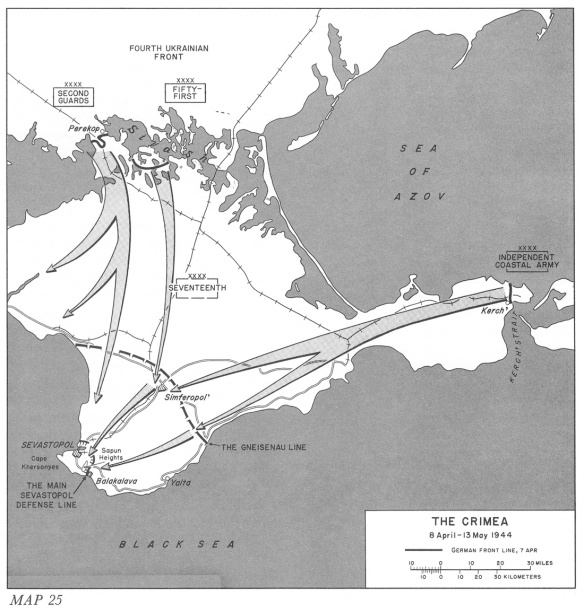

On the Kerch Peninsula, Allmendinger’s V Armeekorps began retreating from its positions during the night of April 9/10. His troops had to retreat over 100 miles to reach relative safety around Sevastopol, and Eremenko’s Coastal Army was hard on his heels. Eremenko had three rifle corps – the 3rd Mountain, 16th, and 11th Guards – comprising ten rifle divisions and two naval infantry brigades. His armor force was relatively small – just Colonel Aleksandr Rudakov’s 63rd Tank Brigade, three independent tank regiments, and a self-propelled artillery unit – with a total of 204 tanks and assault guns. The German retreat was relatively sloppy, with no effort at deception, and Eremenko launched a hasty attack that destroyed FEB 85 and wiped out company-size rearguards from the 73. and 98. Infanterie-Divisionen. It was clear that Axis morale in the Crimea was collapsing and that no one wanted to be left behind – all thoughts were on getting to Sevastopol and the evacuation ships. In contrast, Soviet morale was sky-high, and Eremenko’s Coastal Army had not suffered heavy losses. On the morning of April 11 Eremenko’s troops entered Kerch to occupy an empty and devastated city. Meanwhile, the bombers of the 4th Air Army viciously attacked Allmendinger’s retreating columns. Since there was only a single main road leading west, Allmendinger’s entire corps was stretched out along it – making easy targets for low-level strafing. Most of the German artillery was horse-drawn, which could not retreat very fast. Oberst Karl Faulhaber’s Grenadier-Regiment 282 formed the rearguard, reinforced with motorized flak guns and some antitank guns. Allmendinger was able to get his corps to the Parpach Narrows by April 12, but he could not remain at this position. With the 19th Tank Corps and 2nd Guards Army heading for Simferopol, it was clear that they would soon cut off Allmendinger’s retreat path, so Jaenecke ordered him to instead head for Feodosiya or Sudak, where the Kriesgmarine could evacuate him by sea.

Despite the fact that AOK 17 was in full retreat on all fronts and suffering heavy losses, Hitler would still not authorize a full-scale evacuation of the Crimea. However, he did allow Jaenecke to begin evacuating wounded, as well as non-essential support personnel, but no able-bodied combat troops. In Hitler’s mind, AOK 17 should be able to hold out in Festung Sevastopol for many months, just as Petrov’s army had in 1941–42, although he ignored the fact that the defenses were in very poor condition. Hitler ordered the Luftwaffe to slow the Soviet advance in order to buy time for AOK 17 to organize a defense of the port, but Soviet tanks had already overrun German airfields at Bagerovo and Karankut, which seriously disrupted Luftwaffe air operations at a critical moment. All German air units in the Crimea were forced to relocate to the small airfields at Sevastopol. Fritz Morzik’s transport fleet hurriedly brought in ammunition to replace the stocks lost in the Perekop and Sivash fighting, while evacuating hundreds of wounded troops. Hitler also order the Fliegerkorps I headquarters to return to the Crimea to control air operations, while directing Luftflotte 4 to provide air support from its bases in Romania. The He-111 bombers of KG 27 and Bf 110 fighters of II./ZG 1 intervened in an effort to stem the Soviet armored pursuit, but it was too little and too late.

On April 13 the Soviet pursuit reached its flood tide, as the 19th Tank Corps liberated Simferopol and Yevpatoriya. Jaenecke evacuated his headquarters from Simferopol just 12 hours before the Soviet tanks arrived. Eremenko pursued Allmendinger’s V Armeekorps with the 227th Rifle Division and 257th Independent Tank Regiment in the lead. After liberating an abandoned Feodosiya, Eremenko’s advance guard caught up with the tail end of Allmendinger’s V Armeekorps near Stary Krim. Antitank gunners from Panzerjäger-Abteilung 198 ambushed and destroyed several T-34s, but the Soviets would soon overwhelm the rearguard unless something was done. Major Walter Kopp’s Gebirgs-Jäger-Regiment Krim, relatively unengaged up to this point, was ordered to make a stand in the hilly terrain in order that the rest of the corps could escape unmolested to Sudak. Kopp’s mountain troops put up a desperate resistance that temporarily halted Eremenko’s pursuit, but most of Kopp’s regiment was sacrificed in the process. The Germans also deliberately left supply dumps intact, knowing that the Soviet penchant for looting would slow their pursuit. At Sudak, MFPs from the 1. Landungs-Flotille arrived and began transfering troops from V Armeekorps to Balaklava. However, it was not long before the VVS-ChF detected the Kriegsmarine operation and sent its bombers to disrupt the evacuation. The Luftwaffe was too preoccupied relocating to alternate airbases, so they failed to protect the evacuation and Soviet bombers had a field day, ripping apart the slow-moving MFPs with bombs and cannon. About 10,000 troops from Allmendinger’s corps were evacuated to Balaklava by sea, but the rest would have to retreat through the partisan-infested Yaila Mountains.

Surprisingly, the partisans did not seriously interfere with Allmendinger’s retreat, after a few displays of firepower. This was a chance for the Crimean partisans to make a decisive contribution to victory, by delaying the retreat of V Armeekorps, but they missed it. Instead, they waited for the Red Army’s tanks to appear, then emerged to join in the numerous photo opportunities that liberation afforded. Had the partisans inflicted delay upon Allmendinger’s retreating corps, there is a good possibility that AOK 17 would have been unable to make even a brief stand at Sevastopol and that the city would have been overrun before a naval evacuation could occur.

Instead, Lieutenant-General Hugo Schwab, commander of the Romanian Mountain Corps, deployed two battalions to help cover the retreat of V Armeekorps along the coast road and to prevent sabotage by partisans. By the morning of April 14, V Armeekorps reached Alushta and continued to move through the town as the Romanian battalions formed blocking positions. Many of the remaining horses were shot in Alushta because they were slowing the retreat, and artillerymen removed the breechblocks from their guns and threw them into the sea. The Germans promised to evacuate the two Romanian rearguard battalions with MFPs from Alushta, but in the confusion of the retreat the Romanians were abandoned. At dawn on April 15, Eremenko’s vanguard struck the Romanians in force, and, after several hours of a delaying fight, they began retreating toward the perceived safety of naval evacuation from Alushta. However, upon reaching the town, the Romanians found the Germans gone and Soviet troops blocking the coast road. The two Romanian battalions attempted to infiltrate westward along secondary roads in the mountains, but they were eventually encircled and destroyed – only three survivors made it to Sevastopol. Schwab was incensed that the Germans had allowed his rearguard battalions to be destroyed, and Axis relations began to deteriorate during the retreat. Meanwhile, the German V Armeekorps reached Yalta on April 15, and Eremenko’s pursuit had fallen behind due to the sacrifice of the Romanian battalions. Allmendinger apparently felt safe enough in Yalta to pause for a good meal and a night’s sleep in the officer’s rest home, which had served as an R & R area for Axis troops since 1942. Generalleutnant Alfred Reinhardt, the commander of the 98. Infanterie-Division, had to remonstrate with Allmendinger to keep moving, lest the Soviet pursuit catch them bunched up on the coast road. Schwab was further angered that the Germans found time to rest while the Romanian rearguard was being annihilated. Finally, after five days of retreating, V Armeekorps reached the eastern outskirts of Sevastopol on April 16. However, the cost of this successful retreat was very high, with over 70 percent of Allmendinger’s artillery and heavy weapons lost, as well as thousands of troops – the survivors were in no shape to conduct defensive operations.

Meanwhile, Gruppe Konrad had fallen back precipitously from the Ishun position, but a good part of the artillery was saved thanks to the rearguard fought by two batteries of the Sturmgeschütz-Brigade 279. Elements of the Soviet 19th Tank Corps actually got ahead of the retreating Germans – just as Brigade Ziegler had done to Petrov’s retreating army in 1941. German columns were forced to form all-around defensive hedgehogs at nightfall, lest they be surprised and attacked by marauding Soviet mechanized units. One Romanian battalion that did not form a hedgehog was caught by Soviet tanks and opted to surrender. In another ambush, the Soviets managed to knock out two StuG III assault guns, but the rest of Sturmgeschütz Brigade 279 fought its way out of the enemy ambush. By the time that Gruppe Konrad reached the Gneisenau Line on April 12/13, it found its retreat route blocked by Soviet forces and was obliged to fight its way through the Kessel forming around them. Gruppe Konrad succeeded in fighting through the Soviet pincers, but only by retreating as fast as possible. The Romanian 19th Infantry Division was hard pressed by the Soviet tankers, and some of its battalions were destroyed.

Contrary to what Hitler thought, Sevastopol was not prepared for another siege. A total of seven Romanian mountain-infantry battalions were manning a thin outer perimeter, which was much weaker than the Soviet positions of 1942. German naval engineers had repaired a few flak positions and built some additional bunkers, but very little had actually been done to prepare the naval base for a ground attack. The man on the spot was Oberst Paul Betz, an engineer officer, who had been designated as commander of Festung Sevastopol just two weeks prior. Betz had spent six months with the Afrikakorps in North Africa, then spent much of 1942–43 as a senior pioneer leader for AOK 17 in the Caucasus. Upon the activation of Adler, he formed a Kampfgruppe from Feldausbildungs Regiment 615 (FAR 615), six flak batteries from Pickert’s 9. Flak-Division, and the Luftwaffe’s armored flak train “Michael.” Betz moved his Kampfgruppe to block the main road to Sevastopol, just south of Bakhchisaray. When the lead elements of Gruppe Konrad arrived late on April 13, Betz was given six of the last operational StuG III assault guns to reinforce his position. At dawn on April 14 the vanguard of the 19th Tank Corps arrived at Bakhchisaray, but Kampfgruppe Betz was able to delay them for 12 critical hours, while Gruppe Konrad withdrew into Sevastopol. Then, Betz broke contact and fell back under the cover of a barrage from Gruppe Konrad’s artillery.

While the Germans retreated, Schwab deployed all three of his mountain divisions on Sevastopol’s perimeter, with the 1st and 2nd Mountain Division barring the direct routes in from the north. On the morning of April 15, the 19th Tank Corps began probing attacks against the Romanian defenses, but the mountain-infantry battalions continued to display combat effectiveness and they knocked out 23 Soviet tanks. It took Konrad 24 hours or more to get the disorganized 50. and 336. Infanterie-Divisionen into the perimeter lines, which meant that it was the Romanians who defeated the initial Soviet attacks on their own. Tolbukhin continued probing the Romanians for the next week, but not in great strength. Tolbukhin apparently believed that the Axis defenses of Sevastopol were much stronger than they really were and that a deliberate attack was necessary, so he decided to wait for his artillery to arrive before mounting a serious offensive. In fact, Jaenecke had fewer than 20,000 organized combat troops left after the retreat. In just nine days, AOK 17 had suffered 29,873 casualties, as well as losing a great deal of its equipment. Allmendinger, who had begun to display odd behavior during the retreat, decided to go on leave for a week, and left V Armeekorps under temporary command of a Romanian mountain-infantry officer – a bizarre action for a German general. The two most effective German units, the assault-gun brigades, were reduced to only a handful of operational vehicles. Luftwaffe air support dwindled after the loss of 70 aircraft, and fewer than 50 aircraft remained operational in the Crimea, including 16 Bf-109s and 21 ground-attack aircraft. Simply put, AOK 17 was no longer capable of effective resistance.