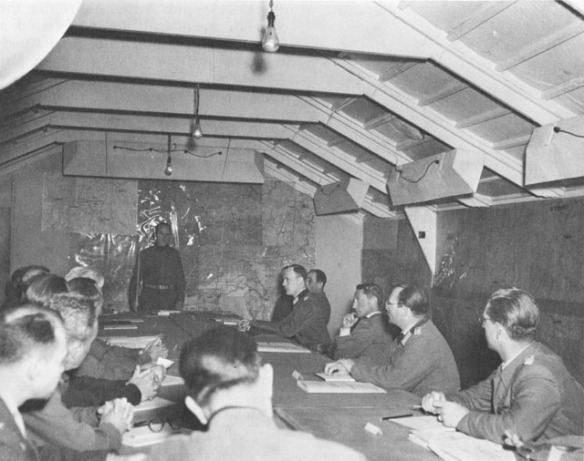

German representatives receive instructions from General Gruenther.

General von Senger surrenders to General Clark at Fifteenth Army Group headquarters.

Karl Friedrich “Fritz” Wilhelm Schulz (15 October 1897 – 30 November 1976) was a German general of infantry, serving during World War II and recipient of the Knight’s Cross with Oak Leaves and Swords. The Knight’s Cross of the Iron Cross and its higher grade Oak Leaves and Swords was awarded to recognise extreme battlefield bravery or successful military leadership.

Army Group C, Schweinitz and Wenner discovered upon reaching Bolzano, was no longer under von Vietinghoff’s command. Hofer having by telephone charged von Vietinghoff and his chief of staff, General Roettiger, with treasonable contact with the Allies, Kesselring had relieved both officers and placed Army Group C under the Army Group G commander, General Friedrich Schulz. Kesselring referred SS General Wolff’s case to the chief of the RSHA, Dr. Kaltenbrunner, for disciplinary action. Kaltenbrunner had, in the meantime, left Berlin to take refuge in upper Austria, where he was engaged in a wild and hopeless effort to take over surrender negotiations and arrange, through conservative clerical circles, a separate peace for Austria.

At noon on the 30th General Schulz and his chief of staff, General Wentzell, had arrived to assume command of Army Group C. Von Vietinghoff immediately turned over his command to Schulz, but Roettiger, unwilling to abandon the scene, decided to remain in his office for a day or so, ostensibly to “orient” his successor. Determined to carry out Kesselring’s intent for Army Group C to continue to resist in hope of gaining time for other forces elsewhere to elude the Russians, General Schulz ordered all subordinate units to fight on.

The situation on 1 May was such that the order was manifestly impossible to execute. In northwestern Italy virtually all resistance had already ceased and north of Lake Garda and in the Brenta and Piave valleys the remnants of the two German armies were backed up against the Alps.

At that point Roettiger emerged as the key figure in an attempt to force Kesselring to abandon his plan and permit the capitulation to take place at the appointed hour. Instead of allowing von Schweinitz and Wenner to report directly to the new army group commander, Roettiger had them brought to his own quarters were they were joined by General Wolff and SS Standartenfuehrer Dollmann. All agreed that without Kesselring’s authorization neither Schulz nor Wentzell would order the cease-fire. If there was to be an immediate cease-fire, there was no alternative, Roettiger and Wolff agreed, to taking Schulz and Wentzell into custody and themselves issuing a cease-fire order.

Events at Army Group C headquarters thus acquired the character of opéra bouffe. To prevent word from reaching Kesselring, Roettiger and Wolff, with the co-operation of the army group intelligence officer, blocked all communications between Bolzano and the Reich. Moving rapidly, they thereupon seized Schulz and Wentzell soon after daylight on 1 May and confined them to their quarters under house arrest.

In de facto command of Army Group C, Roettiger issued the cease-fire order, but he had failed to reckon with the hold that military protocol and tradition still had on his fellow officers. When two of the army commanders, Lemelsen and Herr, learned that Schulz and Wentzell were under house arrest, they refused to implement Roettiger’s orders even though they had agreed in principle with the decision to surrender. That left Roettiger with no choice but to release Schulz and Wentzell and attempt to win them over by argument. At Wolff’s insistence, Schulz called a meeting of all the senior commanders for 1800 at army group headquarters, which Roettiger and Vietinghoff would be allowed to attend.

While that bizarre drama was being played out, the XIV Panzer Corps commander, General von Senger, had moved with his corps staff to Mattarello, three miles south of Trento. There, “in a pretty country house with a baroque garden and a wide view into the Adige valley,” he awaited word of the capitulation.

That afternoon Senger received a call from Lemelsen asking him to take his place at the army command post because he had just been summoned to a meeting at army group headquarters. Arriving at army headquarters that evening, von Senger learned details of the capitulation that had been signed at Caserta on the 29th and that Lemelsen and Herr, as well as General Pohl, the air force commander in Italy, and SS Obergruppenfuehrer Wolff, had all concurred in the action.

In the meantime, a teletype message from Admiral Doenitz reached Army Group C headquarters, telling of the Fuehrer’s death in Berlin and announcing that, in accordance with the Fuehrer’s will, Doenitz was Chief of State and Commander-in-Chief of the Armed Forces. Doenitz’s message also ordered the German armies to continue to fight against the Western Allies so long as they interfered with the battle against Bolshevism.

In view of that order–or exhortation–Schulz hesitated to support the pro-capitulation faction at army group headquarters. Yet from the two army commanders he learned that they no longer considered their armies capable of meaningful resistance, so that continuation of the war in Italy no longer made sense. Wolff and Pohl added that with partisans already in control of wide areas of German-occupied Italy, the political situation there was equally hopeless. Even so Schulz merely agreed to pass that information on to Kesselring; he still refused to issue a cease-fire order without the field marshal’s approval.

Unaware of the machinations within the German command and concerned that the emissaries might not have reached Bolzano, Field Marshal Alexander, meanwhile, in another message to von Vietinghoff demanded an unequivocal answer to whether he accepted the terms of surrender and whether his force would cease fire at the agreed time. The message arrived at Army Group C at 2130 on 1 May. Its stern tone convinced even Schulz that a final decision could no longer be deferred.

After advising the Allied commander that a decision would be made within the hour, Schulz telephoned Kesselring’s headquarters only to learn after he finally got through that the field marshal was at the front and that his chief of staff was unwilling to make a decision. Wolff then got on the telephone and angrily insisted that since all were agreed that further resistance was futile, one of Army Group C’s senior commanders should be given authority to issue the cease-fire order. To that the chief of staff lamely replied that he would lay the matter before the field marshal when the latter returned that night.

When by 2200 no word had been received from Kesselring’s headquarters, Lemelsen and Herr at last agreed to issue the orders on their own responsibility. Later that night Lemelsen telephoned von Senger to tell him to order a cease-fire as of 1400 on the 2d–two hours later than the time agreed upon at Caserta–and to halt all troop movements except those necessary for supply. Von Senger immediately transmitted the orders to the LI Mountain and the XIV Panzer Corps, as well as to the I Parachute Corps, which in the confusion of the past week had come under the control of the Fourteenth Army. The Tenth Army’s LXXVI Panzer Corps having surrendered a week before, Herr had little trouble communicating the orders to the few troops still under his command.

While there were no objections or demands for explanation from any of the corps headquarters, it soon became evident at army group headquarters that many younger officers were determined to fight on. To avoid a showdown with the young zealots, Wolff, Pohl, and the two army commanders took refuge in Wolff’s headquarters where the SS general had prudently assembled seven tanks and 350 SS troops.

They acted just in time, for at 0115 on 2 May an order arrived from Kesselring for the arrest of Roettiger, von Schweinitz, and von Vietinghoff. Although the order made no mention of the army commanders, both Herr and Lemelsen found it prudent to depart for the relative security of their own headquarters. A similar order from Kesselring’s air officer for the arrest of General Pohl reached Pohl’s adjutant, who quietly ignored it.

Before the arrests could be carried out, Kesselring telephoned Wolff in his barricaded headquarters and upbraided him for attempting to usurp his, Kesselring’s, authority as commander of the southwestern theater. For two hours the two officers argued bitterly until connections became bad, whereupon the chiefs of staff of the two commanders resumed the argument. Toward the end of the marathon and sometimes acrimonious debate, even Schulz joined in, supporting Wolff’s contention that since further resistance was impossible Kesselring would only be agreeing to a fait accompli.

Not until 0430 on 2 May did Kesselring finally agree to authorize Schulz to issue a cease-fire order–limited to the sphere of command of OB Suedwest. Wolff then sent word of Kesselring’s acceptance of the “written and verbal conditions of the Armistice Agreement” to Alexander with a request that public announcement be withheld for forty-eight hours. The Allied commander agreed to relay the request to his superiors but insisted that Wolff was “to carry out your agreement to cease hostilities on my front at 12 noon GMT today [2 May].” The Germans, after a two-hour delay, broadcast cease-fire orders to their troops at 1400. When the Allied command picked up their broadcast, Alexander announced the cease-fire four and a half hours later at 1830.

Field Marshal Kesselring meanwhile placed himself at Grand Admiral Karl Doenitz’s disposal for “this arbitrary and punishable action.” At the same time, he asked Doenitz’s authority to arrange for surrender of the remaining two army groups, G and E. Although the Admiral approved Kesselring’s action in regard to Army Group C, he refused to authorize capitulation of the two other army groups.

Back at headquarters of the XIV Panzer Corps on the morning of 2 May, General von Senger, explaining the surrender, fully emphasized that Kesselring had approved it, for the field marshal’s name still enjoyed considerable prestige among the officers and men. “It was,” von Senger noted in his diary, “a tragic moment, the complete defeat and the imminent surrender after a fight lasting six years, tragic even for those who [like himself] had foreseen it for a long time.”

At Army Group C’s behest von Senger then left to head a mission to the Allied 15th Army Group headquarters at Florence to arrange for implementation of the surrender agreement. Under the escort of Brig. Gen. David L. Ruffner, deputy commander of the 10th Mountain Division, and a British colonel, von Senger and a small party that included von Schweinitz traveled south along Lake Garda’s eastern shore, taking to the windswept waters in DUKW’s to bypass the damaged tunnels, and at about 2100 arrived cold and wet at the 10th Mountain Division’s command post. Transferring to staff cars and exchanging General Ruffner for General Hays, the party set out for Verona, where they spent the night, then flew to Clark’s headquarters at Florence.

At 1030 on 4 May the German commander appeared before his long-time adversary in the van that Clark used as an office. Von Senger presented a gaunt and haggard appearance. Saluting Clark and other senior American commanders crowded into the little van, he reported formally in English that as General von Vietinghoff’s representative he had come to receive his instructions consistent with the terms of surrender signed at Caserta. Did he have full authority to implement the terms of unconditional surrender, Clark asked. Von Senger replied that he had. Handing him detailed instructions for the surrender, Clark told him to withdraw with General Gruenther and other members of Clark’s staff for full explanation of these instructions.

During the conference with Gruenther, von Senger and his staff pointed out that until the Allied forces arrived in the German-held areas, armed bands of partisans roaming the countryside would make it difficult, if not impossible, for the Germans to lay down their arms and at the same time protect their supply depots, which by the terms of surrender were to be turned over to the Allied forces and not to irregulars. That was a crucial point, for General Clark was anxious to prevent additional arms from falling into the hands of Communist-controlled partisans who constituted one of the largest and most active groups in the Italian resistance.

The problem was deemed serious enough to refer back to Clark. What von Senger essentially wanted was for the Allied commander to restrain the partisan bands. That Clark agreed to do, although he noted that, having just given them a “signal to go in for the kill,” it would be pretty hard to squelch all that ardor through radio messages. The best solution would be to get the American troops as quickly as possible into those areas still occupied by the Germans.

This had to be carefully arranged, for to rush American troops into German-occupied areas before all German units had gotten word of the surrender was to invite possible bloodshed. General Truscott had thus held Keyes’ II Corps in place since early on 2 May to allow the German command in the area east of Lake Garda and in the Piave and Brenta valleys ample time to get word of the cease-fire to all units, many isolated and lacking regular military communications with their headquarters. Some German units took advantage of the delay to attempt escape through the Alpine passes into Austria, in spite of a standfast order. Aerial reconnaissance reported over a thousand horse-drawn vehicles and more than 500 motor vehicles mixed with civilian traffic passing through Bolzano in the direction of the Brenner Pass. Deterred by poor weather conditions and reluctant to cause further bloodshed, Allied pilots made no effort to attack the columns.

Satisfied by 3 May that all German units had received the cease-fire order, Truscott let Keyes’ II Corps resume roundup operations. Northeast of Lake Garda the 85th and 88th Divisions sent small task forces up the Piave and Brenta valleys toward the Austrian frontier. Early on 4 May the 339th Infantry crossed the frontier near Dobbiaco, forty miles east of the Brenner Pass, and a few hours later a reconnaissance unit from the 349th Infantry met troops from the Seventh Army’s VI Corps at Vipiteno, nine miles to the south of the Brenner. Later in the day, the 338th Infantry, advancing astride Highway 12, reached the frontier at the Brenner Pass. The next day, 5 May, the 10th Mountain Division, after passing through Bolzano, turned northwestward via Merano and reached the Austrian frontier over the Reschen pass. Just beyond the pass, at the Austrian village of Nauders, the mountain infantrymen made their first contact with those German troops retreating before the U.S. Seventh Army. Aware that the Seventh Army had already received a surrender delegation from Army Group G, General Hays halted his men just outside Nauders. On 6 May, following surrender of Army Group G at noon, elements of the 10th Mountain Division continued northward to establish contact with troops of the Seventh Army’s VI Corps, Truscott’s former command.

In northwestern Italy throughout 3 May the divisions of the IV Corps–the 1st Armored and the 34th, 91st, and 92d Infantry Divisions–had continued to accept the capitulation of isolated enemy units that had not yet received word of the general surrender. Faced with a choice of surrendering to the French, the Americans, or partisans, most of the Germans gave themselves up readily, even eagerly, to the Americans.

Meanwhile, on 1 May, the Eighth Army had contacted Tito’s partisans at Montfalcone, about 17 miles northwest of Trieste. Although for many months an uneasy confrontation would remain between the Western Allies and the Yugoslavs along the Isonzo and at Trieste, northeastern Italy rapidly settled down to welcome though tense peace. By 6 May the occupation of all Italy from the Straits of Messina to the Alps had been completed. The eastern, western, and northern frontiers were closed, with all major exits under Allied control. In spite of the protracted negotiations, which had reached a point of dramatic tension through frequent covert comings and goings across international frontiers, the end came in Italy, as it would in northern Europe, only after the German forces, defeated in the field, had been backed into corners of Europe from which there was neither escape nor hope of survival. Only then did the Germans finally lay down their arms.