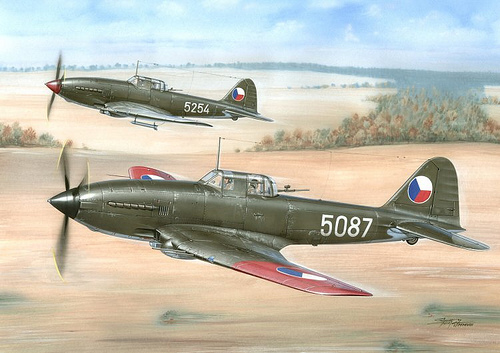

Ilyushin Il-10 (Avia B-33) Czechoslovak Air Force

World War I

In the First World War, the Czechs served in the Austro-Hungarian army, but mass desertions were widespread. Czechoslovak legions were formed in France, Italy and Russia to fight for Czechoslovak independence from Austria-Hungary. This is why Czech pilots could be found on both sides of the conflict. Many Czech pilots were trained in France due to the activities of M. R. Stefanik – a Slovak scientist, French pilot and one of the founding fathers of Czechoslovakia.

The Creation of Czechoslovak Air Force

In October 1918, former Czech members of Austro-Hungarian squadrons met on the Zofin island in Prague. At that time nobody knew they were founding one of Europe’s distinguished air forces. Many enthusiastic men gathered around sergeant Kostrba, but there were no planes to fly. That’s why it was a matter of high importance to obtain the largest possible number of aircraft for the republic, and find suitable airfields. Several undamaged airplanes were obtained from the former flying school in Cheb. These were flown to a meadow in Strasnice, which became the first Prague airport. Several foreign types were soon added to the original trainers from Cheb.

The new air force was helped significantly by a French donation of 127 aircraft. This help was not quite as unselfish as it looked: France wanted to gain a new market for their military production in newly created Czechoslovakia.

Young Czech experts opposed attempts to make Czechoslovak aviation dependent on France. Especially well-known designers Alois Smolik, Antonin Vlasak, Antonin Husnik, Pavel Benes and Miroslav Hajn had their own ideas for the Czechoslovak air force. These ideas were very specific, because each of them represented an aircraft manufacturer.

This is why the first tests of Czech made aircraft were eagerly awaited. They were supposed to decide the future of the Czechoslovak aviation industry. The test results of Smolik’s S-1 biplane were favorable for the local aircraft development and production. Final decision was taken after S-1 was joined by Aero Ae-02 and Avia BH-1. Local production beat the import.

At this time Czech aircraft were largely unknown and even ignored abroad. The aircraft of WW1 powers prevailed. It is not surprising that the first Prague Aviation Exhibition in 1920 went unnoticed abroad. The Czechs made up for this at the international aviation meeting in Zurich two years later. Alois Jezek, the company pilot of Letov, came in third with his S-3 in the category of precision takeoff and landing. He was also seventh in aerobatics.

Another company – Avia – also made the country famous. Czechoslovakia was among the first countries to start serial production of low-wing fighters. These were Avia BH-3’s, direct successors to the very first low-wing aircraft in the country – Avia BH-1 Experimental. These were followed by the well-known “Boska”: the exceptionally successful Avia BH-5. This type was made famous by doctor Zdenek Lhota with his competition machine marked L-BOSA: thence the nickname of “Boska”.

Doctor Lhota was an aviation enthusiast who quit his successful practice as a lawyer to link his future with the Avia factory. He gained the first trophy for Czechoslovakia in 1923, winning the Brussels International Tourist Aircraft Contest. His skyrocketing career continued until 1926. In that year he flew to Italy to defend the most valued trophy of the day – Coppa d’Italia Cup – which had been held by Avia since Frantisek Fritsch won the contest in 1925. Doctor Lhota flew the BH-11 low-wing monoplane. He disregarded the designers’ instructions and performed headlong flight during the preparations. This caused a crash and Lhota died together with his engineer Volenik. Czechoslovakia won the trophy anyway. Another pair of pilots, Bican and Kinsky, won the contest and defended the valuable trophy for Czechoslovakia.

The aviation of the 1920’s was not just Avia and doctor Lhota. Frantisek Lehky broke the world record at 100 kilometers with standard load on Aero A-12 on September 7, 1924. Karel Fritsch won the above mentioned Coppa d’Italia in Rome in November 1925, and one year later pilot Stanovsky undertook a long distance flight with Aero A-11. This was a trip around Europe across the tip of Africa and Asia Minor.

Captain Malkovsky was among the best Czechoslovak pilots of the late 1920s. He started the tradition of Czech aerobatics. His red Avia BH-21 was the top attraction of most public shows, and he was one of the first pilots in the country to master higher aerobatics. Unfortunately, he got killed at an air show in Karlovy Vary in 1930. Other distinguished personalities of pre-war aerobatics include Hubacek, Novak and Siroky. Frantisek Novak, in particular, is considered the best Czechoslovak aerobatic pilot of all time.

The Avia factory was the avant-garde: their low-wing series was very much ahead of its time. On the other hand, these planes had various problems, especially in that they required careful control. Most pilots were used to comfortable flying with stable biplanes, so there were many accidents with Avia monoplanes. This is why the company had to switch to biplanes. The designers did a good job again building the above mentioned biplane Avia BH-21, made famous by captain Malkovsky. Other famous Avia types included the best Czech serial fighter B-534, as well as modern low-wing planes B-35 and B-135. These last two types were built just before WW2, and were still undergoing further development in 1938 when Czechoslovakia was dismembered by Germany. Later, these planes were seized by the Germans, just like the entire country. Avia B-35 was a very promising design. Its prototype was flown with fixed landing gear, and an engine from the B-534 because the gear and engine intended for this plane were not ready yet. In spite of this, the aircraft achieved the speed of 480 kmph and showed excellent handling qualities. After the German takeover its development continued. It resulted in Avia B-135. Twelve of these machines were sold to Bulgaria in 1941 together with the manufacturing license. It is too bad this plane was developed so late and never had the opportunity to oppose the German army. It can be assumed this plane would have been a worthy opponent for the Messerschmitt.

Avia B-534 was an excellent machine, and its only fault was that it was not replaced in time. It was used by many air forces well into the war. The last biplane kill of WW2 was scored by F. Cyprich flying an Avia B-534 on September 2, 1944. This was in the Slovak uprising, and the plane shot down was a German Ju 52/3m in the area of Radvan.

The Letov factory continued with their successful line started by the Letov S-1 biplane. This light bomber had a wooden airframe with canvas cover. The 1926 S-16 model is among the best of Smolik’s designs. This biplane was used by lieutenant-colonel Skala and engineer Taufr for their long distance flight to Japan. The most modern of Smolik’s design was a full-metal two engine bomber S-50. It was also seized by the Nazis.

The Aero company also started with biplanes. The very first Aero design, the Ae-02 fighter, was a success. It was followed by a reconnaissance biplane A-12, and a very interesting high-wing bomber A-42. The 1930 design was the most modern Czech bomber of the day. Due to some of its faults and the lack of understanding in the military administration, this plane stayed a prototype. Aero also attempted a fighter monoplane A-102, but this project was abandoned when Avia came up with a more modern design (B-35). Aero produced the most modern Czech pre-war bombers (with the exception of Avia’s licensed production of the Soviet SB-2 bomber). These bombers were Aero A-300 and A-304. They too were captured by the Nazis.

These lines create the impression that the Czechoslovak aviation industry only consisted of Avia, Letov and Aero. In reality, there were other companies such as Praga, Tatra, Zlin, Benes-Mraz, as well as designers including Jaroslav Slechta, Karel Tomas, Frantisek Novotny, Robert Nebesar and Jaroslav Lonek.

The Czechoslovak air force and aviation industry played a distinguished role between the wars. It was not the fault of Czech pilots or their machines that they never got the chance to stand up to the enemy.