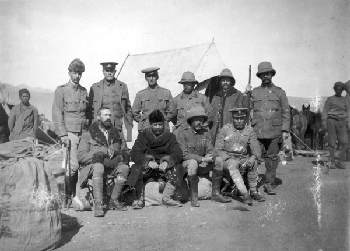

Major Francis Younghusband leading a British force to Lhasa in 1904.

Tibet

Few westerners traveled to Tibet before the twentieth century. In 1707 Capuchin friars established a Catholic mission in Lhasa, and the Jesuit Ippolito Desideri (1684– 1733) lived there from 1716 to 1721. The Catholic mission was abandoned in 1745. Soon the Tibetan authorities closed Tibet to westerners. Nonetheless, by the end of the nineteenth century, two Western empires, British India and Russian Central Asia, abutted Tibet. Despite British suspicions of Russian designs on Tibet, however, Russia had little influence in Lhasa. Britain, on the other hand, was eager to develop trade with Tibet, but the Tibetan government rebuffed British diplomatic contacts. In 1904 a British military expedition commanded by Francis Younghusband (1863–1942) fought its way to Lhasa, forcing the flight of the Thirteenth Dalai Lama (1876–1933) to Mongolia. The British established a consular office in Lhasa, the only Western country to do so. In 1947, upon independence, India inherited the British mission there.

Hong Kong

The primacy given to trade in the colony was reinforced by an imperial policy of discouraging colonial industrialization for fear of competing with British industries. When local industries sprouted in Hong Kong in the 1930s, the colonial government looked at these industries with great skepticism and refused to offer any protection or promotion. In fact, during the first hundred years of British rule, there was little attempt to invest in the colony because of a lack of confidence over the political future of Hong Kong. Economic planning and industrial investment in what the British saw as a borrowed place living on borrowed time were considered politically undesirable. The Communist takeover of China in 1949 and the Communist government’s refusal to recognize the three ‘‘unequal’’ treaties reinforced Britain’s belief that minimal investment in the colony was the right policy.

However, this policy did not imply that Britain simply adopted a hands-off attitude in its rule. On the contrary, the subsequent development of Hong Kong was crafted out of complex interactions between the colonial rulers, British business interests, indigenous inhabitants, and the Chinese migrants who came to the colony either to take advantage of the economic opportunity or to seek refuge from political turbulence in mainland China.

From the outset, the colony faced both cooperation and resistance from its Chinese inhabitants. On the one hand, Britain’s acquisition of Hong Kong depended not only on military strength but also on the indispensable help of Chinese contractors, compradors, and other merchants in providing essential supplies during the Opium War. After the occupation, British businesses relied on preexisting Chinese trading networks to penetrate other Asian markets. In exchange for their collaboration, British authorities rewarded the native Chinese in Hong Kong with social and economic privileges, so that these collaborators became the first generation of Chinese bourgeoisie in the colony.

British attack in Burma 1824.

Burma

In Upper Burma, which remained under Burmese rule until the third Anglo-Burmese war of 1885, the economy became dangerously dependent on the export of mainly cotton and teak. In the teak industry elaborate contracts and concessions were developed over time and honored to such a degree as to warrant substantial investments on the part of British-Indian trading houses. At the same time, in other fields royal monopolies often excluded independent merchants. Rice however had to be imported in ever-larger quantities, which drained Upper Burma of cash. The world depression of the 1870s led to a dramatic decline in prices and plunged the Burmese state into economic hardship and fiscal collapse.

Under British rule Lower Burma developed into an export-oriented economy depending almost totally on rice production. Lower Burma’s rice exports helped make up for food shortages in other parts of the empire. In this sense the colonial state in Burma developed within the context of a larger set of imperial, economic, political, and strategic interests.

Immediately at the end of the third Anglo-Burmese war, with the last Burmese king in exile, several important decisions were taken by the colonial power, which would dramatically change the way Burma was governed. A first attempt to govern through the old royal council, the Hlutdaw, failed. The reforms the British subsequently introduced meant nothing less than a complete dismantling of existing institutions of political authority. They resulted in the undermining of many established structures of social organization. In contrast to India the British decided that Burma would be governed directly, without making use of local elites. The monarchy, the nobility, and the army all disappeared. In the countryside local ruling families lost their positions. The existing political framework vanished. Only in outlying areas like the Shan states did the British use local intermediaries in government. In the heartland of the old Burmese empire, the Irrawaddy Valley, the colonial rulers imposed bureaucratic control right down to the village level. A wholly new framework of government rapidly supplanted existing institutions.

From the late nineteenth century onward village headmen were frequent targets of peasant uprisings, indicating how much they were perceived as tools of the colonial administration. At the same time the colonial power failed to adopt the symbols and roles that had legitimized precolonial rulers. The precolonial state had relied for the maintenance of order and security on its intimate involvement with the symbolic and spiritual life of society. The colonial state viewed its role very differently. The British administrators were not only foreigners, their idea of government presumed a marked distinction between the public and private spheres of life. British rule in effect destroyed the Burmese cosmological order and signified for the Burmese the end of a Buddhist World Age. This produced armed resistance in which Buddhist monks played a significant part. Burmese monks fanned rural rebellion, notably during the economic depression of the 1930s. The main causes of rural unrest and rebellions in the 1930s were taxes, usury, and depressed rice prices.