Although the French had been early pioneers of military aviation and had developed important combat aircraft during World War I, few French designs played important roles in World War II. The most significant French bomber was the Liori et Olivier LeO 451. Introduced in 1937, this medium bomber, crewed by four, was driven by two 1,060-horsepower Gnome-Rhone 14N engines and could achieve a top speed of 298 miles per hour. Service ceiling was 29,530 feet, and range was 1,802 miles. The LeO 451 carried a bomb load of 3,086 pounds and was armed with a single 20-millimeter cannon and five 7.5-millimeter machine guns. Only 373 of these aircraft had been delivered to French forces before the armistice was signed with Germany on June 25, 1940. However, more were delivered to the Nazi-controlled Vichy French Air Force.

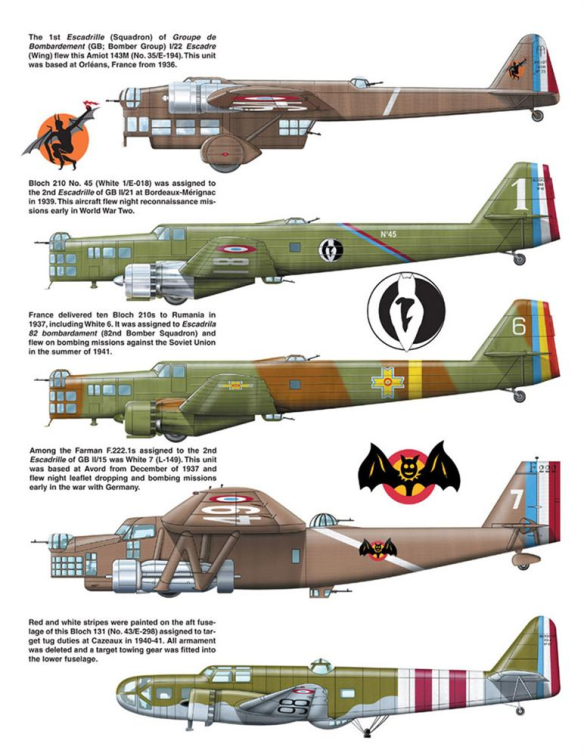

The Amiot 143 was an ugly but functional French bomber of the 1930s. It was still in frontline service at the beginning of World War II and sustained heavy losses.

In 1928 the French government circulated new specifications for an all-metal, four-place bomber capable of operating day or night. Three years later the Amiot Avions Company fielded the first Model 140 prototype, a craft more noted for ugliness than performance. The type underwent additional refinements, which did little to enhance its looks, but in 1934 a revised model, the 143, emerged. This was a cantilevered high-wing monoplane featuring a fully enclosed cockpit, two hand-powered gun turrets, and a lengthy greenhouse gondola on the underside of a narrow fuselage. The wing chords were very broad and the air foil so thick that crew members could reach and service the engines in flight. Finally, the type rested on fixed landing gear covered by streamlined spats 7 feet in length. The first Amiot 143 was acquired in 1935, and a total of 138 were manufactured. It certainly did little to alleviate France’s reputation for designing unattractive aircraft.

The angular Amiot was marginally obsolete by the advent of World War II, but it was still a major bombing type in the Armee de l’Air, equipping five bomb groups. Commencing in 1939, they were primarily used to drop leaflets over Germany and for other propaganda functions. The Battle of France commenced in May 1940, and the lumbering craft began dispensing more lethal cargo. Given their slow speed and light armament, Amiot 143s were usually constrained to night attacks on factories and marshaling yards, dropping 528 tons of bombs. However, they are best remembered for the heroic May 14, 1940, attack on the Meuse River bridges near Sedan. Flying in broad daylight against heavily defended positions, 13 of 14 aircraft committed were lost. Following the French capitulation, many Amiot 143s made their way to Africa and internment while others served the new Vichy regime. All were basically scrapped by 1942.

The elegant Bloch MB 174 was France’s best reconnaissance aircraft of World War II. Fast enough to escape marauding Luftwaffe fighters, they had little opportunity to distinguish themselves.

In 1936 Bloch initiated work on a modern, two or three-seat reconnaissance bomber for the French Armee de l’Air. The prototype first flew in February 1938 as an all-metal, twin-engine, low-wing monoplane. The craft was fitted with twin rudders, as well as retractable landing gear that buried itself in the engine nacelles. This first model possessed an elongated cupola under the fuselage to house a camera or an additional gun position, but this feature was deleted on subsequent models. By January 1939, the aircraft had evolved into the Bloch MB 174, with major modifications. It featured a lengthy greenhouse canopy set farther back along the fuselage than the prototypes. It also possessed an extensively glazed nose and a small bomb bay. Test flights revealed the craft to exhibit excellent performance at all altitudes, so in 1939 it entered production. Persistent problems with overheating resulted in the adoption of smaller propeller spinners on most machines. A small number of bomber versions, the MB 175, had also been constructed. Around 80 machines were built in all.

Bloch MB 174s equipped three groupes de reconnaissance (reconnaissance groups) by the spring of 1940, shortly before the German invasion. At that time they were required to conduct dangerous missions deep into enemy territory, which were accomplished with little loss. With the imminent collapse of France, several MB 174s were flown to North Africa to escape, but most of these excellent craft were destroyed to prevent capture. The surviving machines were subsequently employed by Vichy air units in the defense of Tunisia. The Germans also kept the type in production, taking on 56 machines as trainers. During the immediate postwar period, an additional 80 MB 174Ts were constructed as torpedo-bombers for the French navy. These flew capably until being replaced in 1953 by more modern designs.

The ugly Farman F 222 was the largest French bomber of the interwar period. Its service was undistinguished, but the type mounted the first Allied air raid against Berlin.

The design concept for the Farman family of heavy bombers originated with a 1929 requirement calling for a five-seat aircraft to replace the obsolete LeO 20s. The prototype, designated the F 220, first flew in May 1932 and had all the trappings of a French bomber of this period. It was a high-wing monoplane with wings of considerable chord and thickness, braced by large struts canting inward toward the fuselage. The fuselage itself was very boxy and angular, sporting pronounced nose and dorsal turrets and a smaller ventral position. The four engines were mounted in tandem pods below the wing in pusher/tractor configuration and secured to the fuselage by means of a pair of small winglets. The overall effect was an unattractive, if capable, craft and, being entirely constructed from metal, a signal improvement over earlier bombers. With some refinements it entered production as the F 221 in 1934 and was acquired in small batches. These represented the first four-engine bombers produced by the West at that time.

Looks aside, the Farman F 220 series was strong, reliable, and continually acquired in a series of updated models. The most important was the F 222 of 1938, which featured a redesigned nose section, dihedral on the outer wing sections, and retractable landing gear. However, the Farman aircraft were readily overtaken by aviation technology and rendered obsolete by 1939. They spent the first year of World War II dropping propaganda leaflets over Germany. After the Battle of France commenced in May 1940, several groups of Farman aircraft made numerous nighttime raids against industrial targets in Germany and Italy. It was a Navy F 223, the Jules Verne, that conducted the first Allied raid on Berlin that June. Many subsequently escaped to North Africa and were employed as transports by various regimes until 1944. Total production reached 45 units.

In 1934, Plan I of the air force (which confirmed independence from the army) called for aerial bombing, reconnaissance, and interception missions. However, there was now less rigidity in the definition of each unit’s purpose. At the top, aerial regiments were replaced by air fleets, each divided into air groups, each of those split into squadrons. These groups were assigned to cover one of the five aerial regions of France and Algeria. With Germany’s announcement that it was creating the Luftwaffe, Plan II was enacted, calling for the establishment of a 1,500-aircraft first line of defense. This would be superseded by two other plans, as well as a modification of the air force’s basic structure. In addition, an aerial mobilization plan was put together. However, the World War I notion of bomber units also acting as reconnaissance confused the effective development of an air doctrine.

Pierre Cot, who acted as air minister during the left-wing Popular Front government of 1936-1938, sought to clarify the French air doctrine by having Plan V emphasize fighters. Yet by the time he left office, there was considerable confusion in what an air force should truly do. This had an important impact on later events and may have even affected Prime Minister Edouard Dalladier’s decision to accept Hitler’s demands in Munich in 1938: Not only did the Luftwaffe appear better equipped, but the specificity of missions and machines suggested that the French air force, still missing hundreds of fighters from its projected inventory, might not be able to effectively engage it even in a defensive role. This was, unfortunately, the case when the Luftwaffe attacked in May 1940. Combined with the confusion that reigned among the air force officer corps, the confusion over a proper air doctrine gave Germany a decisive advantage.

By August 1939, the air force had more than 700 fighters, some 440 bombers, and 400 reconnaissance aircraft. Its budget had steadily been increased, doubling, in fact, between 1937 and 1939.

This was insufficient to hold off the German Luftwaffe and Wehrmacht, which brought France to its knees in six weeks. On 15 June 1940, an armistice was declared, with much of the air force now under control of the Vichy government. A small group of Free French Air Force staff was based in England. This latter force would merge with the French air units stationed in North Africa in 1942 and be involved in various air operations, from fighter escort to bombers and reconnaissance. In addition, some French pilots were incorporated into Soviet units.

French efforts included 67,000 air missions and about 600 air victories, of which only 277 can be officially confirmed. The French air force suffered the heavy toll of 557 losses.