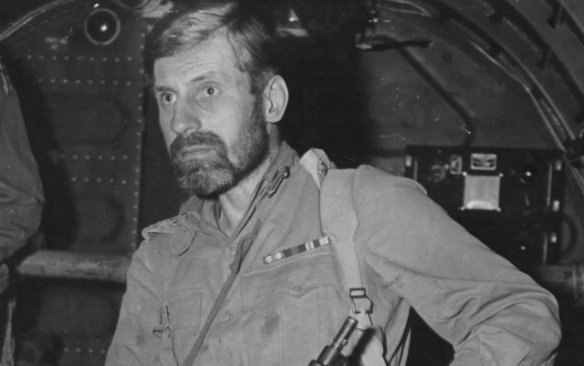

Major General Orde Charles Wingate DSO & Two Bars (26 February 1903 – 24 March 1944) was an officer of the British Army known for his creation of the Chindits deep-penetration missions in Japanese held territory during World War II. Wingate was an exponent of unconventional military thinking and the value of surprise tactics. Assigned to the Mandatory Palestine, he became a supporter of Zionism, and set up a joint British-Jewish counter-insurgency unit. Under the patronage of the area commander Archibald Wavell, Wingate was given increasing latitude to put his ideas into practice during World War II. He created units in Abyssinia and Burma. At a time when Britain was in need of moral-boosting generalship, Wingate attracted Winston Churchill’s attention with a self-reliant aggressive philosophy of war, and was given resources to stage a large scale operation. The last Chindit campaign may have determined the outcome of the Battle of Kohima, although the offensive into India by the Japanese may have occurred because Wingate’s first operation had demonstrated the possibility of moving through the jungle. In practice both Japanese and British forces suffered severe supply problems and malnutrition. Wingate was killed in an aircraft accident late in the war. A continuing controversy over the Chindits has centered around the casualty rate the force suffered, especially from disease. Wingate believed that resistance to infection could be improved by inculcating a tough mental attitude, but medical officers considered his methods unsuited to a tropical environment.

Employing his abundant strategic initiative to the full, he succeeded in outwitting and destroying an even larger army under General Kimura along the Irrawaddy between Meiktila and Mandalay in the spring of 1945, Kimura himself describing Slim’s operation as the ‘masterstroke of allied strategy’.

By the end of 1944 Slim’s forces were powerfully poised on the edge of the central plain of Burma and the Japanese were retreating rapidly. Their speedy retreat posed him a new problem. The drier central plain would give added scope for his armour and motorized units and provide more open targets for the almost unchallenged air forces, but Slim needed – as he had done at Imphal – to draw the Japanese forces into battle and destroy them. He did not want to have to pursue them right through Burma and into Siam or Malaya. He therefore devised a plan which has been rightly praised as his most brilliant concept as a high-level commander. The plan centred on two important towns, Mandalay and Meiktila, and the railway, road and the River Irrawaddy that connected them. Clearly the Japanese would defend Mandalay as stoutly as possible. Slim’s strategem was to have powerful forces advancing towards Mandalay from the north, doing everything possible to convince the Japanese that this was the main assault – including a phoney Corps Headquarters sending real messages. Simultaneously he would send equally powerful forces on a lengthy detour to the west through the Chin Hills, to emerge from the jungle and the hills in the area of Pakokku and then to strike at Meiktila. From there his forces would wheel round to the north and east to intercept and destroy the main Japanese forces before they could retreat from Mandalay.

This, roughly, is what happened, but there is an interesting link back to the controversial Chindit issue. In Defeat into Victory Slim wrote, `My new plan, the details of which were worked out in record time by my devoted staff…had as its intention the destruction of the main Japanese forces in the area of Mandalay.’ He then added the details, that IV Corps would move secretly up the Gangaw Valley, appear at Pakokku and strike violently at Meiktila. When questioned he later confirmed that this plan emerged in discussions with his staff.

At no stage, either in his book or in subsequent discussion, did Slim reveal that on 13 March 1944 he had received a memorandum from Wingate suggesting that the next major Chindit initiative after Broadway, assuming that IV Corps had made a substantial advance, would be to land a brigade at Pakokku, seize Meiktila and trap the Japanese forces before they could retreat from Mandalay. This lack of openness by Slim is well known to the Chindits, and is mentioned by Louis Allen in Burma The Longest War (p. 398). This raises the gravest implications. Not only has Slim claimed the whole of the Meiktila plan as his own when in fact the idea originated with Wingate, but, having had this idea presented to him in March 1944, instead of withdrawing the Chindits after their success at Broadway in order to use them in another ideal situation at Meiktila, he handed them over to Stilwell to be used as normal infantry. The Chindits were never again used as Long Range Penetration Forces; instead, a few months later – after sustaining more than 50 per cent casualties in the slaughter at Mogaung – they were disbanded. Here, clearly, is an added offshoot of the tragic death of Wingate. He would surely have succeeded in arguing his case when, after Broadway, he had Churchill’s personal backing for the Chindits to be used again in the role for which they were armed and trained.

Before Operation Capital got under way, skilful preparations were made by the Royal Engineers and other services – helped by bulldozers, elephants, boat-building operations and by the creation of airstrips – to prepare a route for IV Corps to move secretly on their 300-mile trek into the Chin Hills jungle, and then to emerge undetected near Pakokku. The 17th Indian Division, still led by Cowan, and now extensively retrained and reequipped, took the lead in this venture.

While IV Corps was setting off into the jungle in early January 1945, XXXIII Corps advanced rapidly and captured Shwebo from their old adversaries, 31st Division. From Shwebo 19th Division, under its successful and aggressive commander, Major-General Pete Rees, drove eastwards and crossed the Irrawaddy well to the north of Mandalay. The 2nd Division and 20th Indian Division also made difficult and opposed crossings of the river which in places was over two miles wide, and provided a formidable obstacle when the far bank was held by determined defenders. Sensing their ultimate defeat, the Japanese soldiers did not give up, but rather fought on until every single defender was killed. For weeks these difficult battles continued until by early March, 19th Division was approaching Mandalay. This was a difficult obstacle, and included Fort Dufferin, built by the British in the 19th century, with a deep, wide moat and walls 30 feet thick. On 9 March Rees gave the first of several broadcasts for the BBC with a running commentary on the different actions he could see from his command post within sight of Fort Dufferin. The three divisions attacking Mandalay succeeded in deceiving Kimura into thinking that they were the major attacking force, and any units farther south just a feint.

The move by IV Corps via Pakokku to the fringe of Meiktila proceeded smoothly even though it involved crossing the Irrawaddy in the face of the enemy. All the divisions had hard-fought actions and several near disasters caused by ill-prepared boats, by outboard engines breaking down in the middle of a 2-mile-wide river and by tough Japanese opposition from the far bank.

On 28 February, when XXXIII Corps was already hammering at the suburbs of Mandalay, Cowan launched a well co-ordinated attack on Meiktila. He had 5th Indian Division and 255th Tank Brigade in support, together with motorized units from his division, and additional massed armour and artillery. Cowan surrounded the town and established road-blocks on the main exits. The battle for Meiktila lasted for four days of non-stop fighting with no quarter given. The Japanese had been ordered to defend the city to the last man, and they did virtually that. When they were finally overcome, more than 2,000 corpses were counted, but it was estimated that there were as many again in the bunkers, in the cellars, in the lakes or just blown to pieces by the aerial bombardment. Having been surrounded, the garrison was almost completely wiped out, and a very large stores area – the supply base for two Japanese armies – was captured. Slim, who was present at the battle, considered that, `The capture of Meiktila was a magnificent feat of arms.’

Too late in the day the Japanese reacted to the loss of Meiktila, which was a disastrous blow to their whole position in central Burma, and they put in a series of strong counter-attacks during the following week (6-13 March). They assembled 18th Division from north Burma and a number of units from 53rd Division, 49th Division and the sorry survivors of 33rd Division which had just received another mauling at the hands of their old rivals, 17th Indian Division. With the Indian and British forces now defending Meiktila against a prolonged Japanese counter-attack, which lasted more than a week, the fighting was as close and severe as ever. For example, as units of 5th Indian Division flew into Meiktila airfield their Dakotas came under fire from Japanese automatic and small-arms fire. The battle of Meiktila was one of Cowan’s great victories, but he was under considerable stress because he had just heard that his son had been killed in the attack on Mandalay.

Because of their serious defeats and setbacks at Mandalay and Meiktila, the Japanese tried urgently to regroup their forces. General Honda was ordered to take over 18th and 49th Divisions – called 33rd Army – and to recapture Meiktila at all costs. He thought this plan was foolish, but loyally undertook the task, and on 22 March organized a two-division attack. The first attack was bloodily repulsed, with more than 200 men killed, though the Japanese gunners, skilfully sited and well camouflaged, did considerable damage and destroyed about 50 tanks. Overall, in an operation which lasted several days, while knocking out 50 tanks, they lost more than 50 guns and sustained 2,500 casualties. Honda realized that he could not continue to sustain losses at that level, and he pulled back ready to adopt delaying tactics as he moved south. At the same time, the Japanese 15th Army – made up of the devastated remnants of 31st and 33rd Divisions – were retreating rapidly towards Toungoo. As they fled they were ambushed and attacked by Gracey’s 20th Division which had driven swiftly south from Mandalay. They wrought havoc on the so-called 15th Army – killing more than 3,000 men and capturing large quantities of guns and equipment. These decimated Japanese units, though partly reinforced, contained most of the survivors of the battles at Kohima, at Bishenpur, the Shenam Saddle and Mount Molvom.