The Eastern Empire (from this time referred to as Byzantine) escaped the fate of the west, and continued to flourish under a series of capable emperors. In the first half of the 6th century, the Emperor Justinian even re conquered of some of the lost western provinces: North Africa, where the Vandal kingdom fell in 533; Italy and Sicily, where the Byzantines retained a foothold for over 200 years; and Spain. The hold on Spain proved tenuous, however, and most of Italy fell to the Lombards in 568. By the middle of the following century, Slavs in the Balkans and Arabs in the Near East and North Africa had stripped Byzantium of much of its territory. From this point, the empire was just one of several states jockeying for power in the Mediterranean world of the early Middle Ages.

#

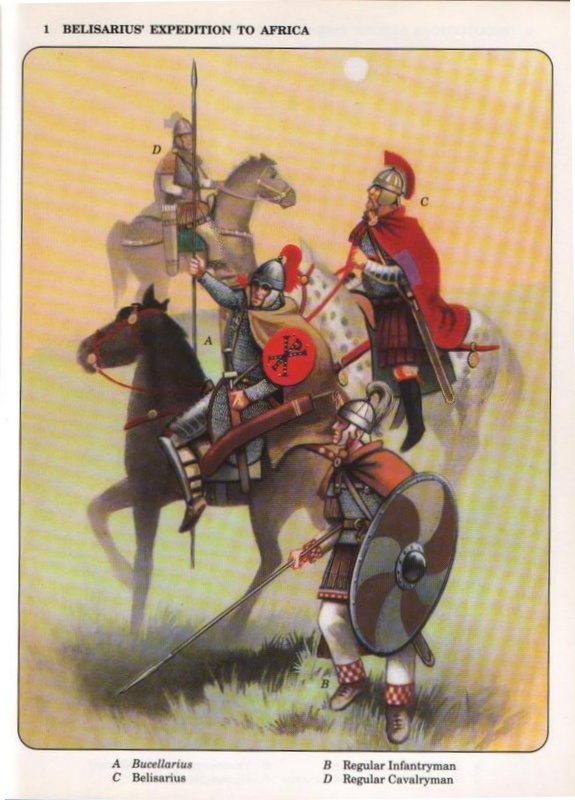

The changes from the sixth century are more minor modifications than responses to western collapse. At the end of the fifth century Anastasius (491–518) created a command of the Long Walls for the local defence of Constantinople, commanded by a vicarius of the praesental army and supplied by a vicarius of the eastern praetorian prefect (Justinian, Nov. 26 (535)). Units of field army troops continued to be assigned to border commands. This caused problems on some occasions, forcing Anastasius to issue a law in 492 making it explicit that duces were in command of all comitatenses troops in their area of responsibility. Under Justinian (527–65) there were more significant changes. The eastern field army was divided into two sectors in 528. In the north was a newpost of magister militum per Armeniam (based at Theodosiopolis), who had direct authority over the five Armenian ducates; the south remained under the magister militum per Orientem. Extra duces were added to the eastern army’s command, at Circesium in Mesopotamia and Palmyra in Phoenice Libanensis. The two vicarii of the Long Walls were replaced in 535 with a single praetor Thraciae with military and logistical duties. The large expeditionary forces sent to the west in 468, 533 and 535 were all created by pooling various field army units under a magister militum drawn from elsewhere in the empire. Thus Basiliscus (whose 468 expedition against the Vandals included western troops) was either magister militum per Thracias or an eastern praesental magister militum (Priscus fr. 53.1). Belisarius invaded Africa and Italy as magister militum per Orientem. Following the Justinianic reconquests new field armies were created under magistri militum in Africa (in 534 based at Carthage), Italy (554? at Ravenna) and Spain (552?). At the same time limitanei units were re-established in Africa and possibly byNarses in Italy. Although Procopius stated that eastern frontier troops were not paid by Justinian, this is an exaggeration.

#

After the changes under the tetrarchy, the next major change was the development of a new type of cavalry regiment called foederati in the late fourth century. Thesewere permanently established cavalry units, with titles like Honoriaci. Their duties were the same as those of regular regiments, e.g. sent to reinforce Africa in the 420s or deployed to garrison Italy against the Vandals in the 440s. Since foederati were initially deliberately recruited from barbarians, many units had a distinct identity, like the Saracens used against the Goths in 378, the Alans in the 401–2 campaign, or the Huns led by Olympius in 409. However, this ethnic identity was the result of their recent recruitment and would have become weaker over time as casualties were replaced by men of various origins within and beyond the empire.

Roman field armies were often supplemented by allied barbarians (variously and loosely described as foederati, auxilia, symmachoi, misthotoi or homaichmiai). Allies were summoned by the Romans for a single campaign and dismissed at the end of it. They were used as single units, organized and fighting in their own fashion, but supplied by the Romans. Many of these forces came from the Danube. Licinius had a large number of Goths fighting for him in the 324 campaign against Constantine, Theodosius usedGoths against Eugenius in 394 and Zeno sent Goths against Illus in 484.65 In the sixth century, Hun allies were used in Lazica in 556 and in Italy, with Narses paying off Lombard allies in Italy in 552 (Agathias 3.17.5; Procop. Wars 8.33.2). These forces came under Roman strategic command: thus during the Frigidus campaign of 394, the Roman officers Bacurius (magister militum?), Gainas (comes) and Saul (rank unknown) commanded the allied contingents in Theodosius’ army. But the actual allied contingents were led by their own leaders, so that Alaric fought at the Frigidus in 394 and in 556, a force of Hunnic Sabiri fought with the Roman army in Lazica under Iliger, Balmach and Cutilzis (Zos. 4.57.2; John of Antioch fr. 187; Agathias 3.17.5). In some cases allied leaders were given Roman positions, like Theoderic Strabo who was magister militum praesentalis in 473 or Cutzinas in north Africa in the late 540s (Malchus fr. 2; Corippus, Iohannis 6.247). In the east, the Romans had semi-permanent arrangements with a number of Arab dynasties (Tanukh, Salih, Ghassan, Kinda), from at least the early fourth century to the seventh century. The leaders of these groups were called phylarchi by the Romans.

Throughout its history, the late Roman army was a standing professional force. Although it failed to perform well on some occasions, the loss of the western territories cannot be attributed to structural failure. There was no major change in the structure of the Roman army during most of this period. Justinian reconquered Italy and Africa in the sixth century with armies similar to those destroyed in the fifth-century west. The outstanding characteristics of the army were continuing small-scale change and institutional flexibility. But if the army was not structurally weak, why did the western Empire fall in the fifth century and the eastern Empire suffer so grievously in the seventh century? Good armies can and do lose wars. In the fifth century the Empire suffered irremediable problems only after the loss of Africa to the Vandals. Africa’s importance is shown by the series of efforts to recapture it, ultimately successful in 533. In the seventh century financial exhaustion from the Persian wars explains much of the Roman inability to deal with the Arab attacks.