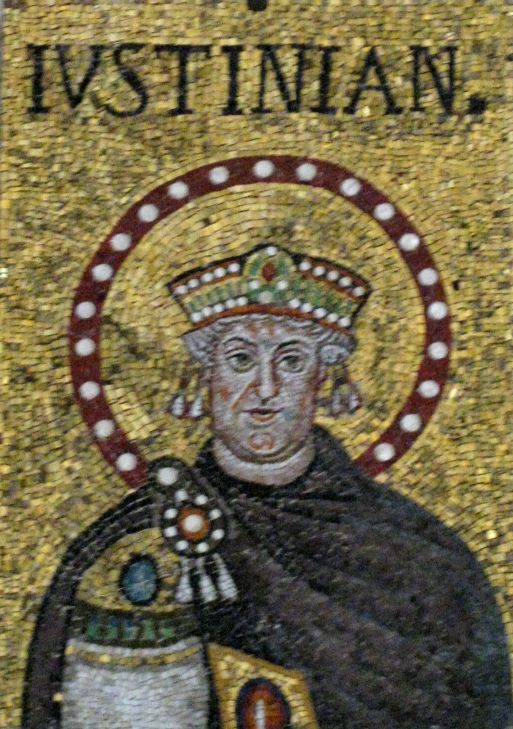

The Eastern Empire (from this time referred to as Byzantine) escaped the fate of the west, and continued to flourish under a series of capable emperors. In the first half of the 6th century, the Emperor Justinian even re conquered of some of the lost western provinces: North Africa, where the Vandal kingdom fell in 533; Italy and Sicily, where the Byzantines retained a foothold for over 200 years; and Spain. The hold on Spain proved tenuous, however, and most of Italy fell to the Lombards in 568. By the middle of the following century, Slavs in the Balkans and Arabs in the Near East and North Africa had stripped Byzantium of much of its territory. From this point, the empire was just one of several states jockeying for power in the Mediterranean world of the early Middle Ages.

#

The sixth century witnessed a significant change in the pattern of military challenges to imperial power. Apart from Vitalian’s unsuccessful revolt against Anastasius, there were no attempts by commanders to seize or exercise a controlling influence over imperial power. Military challenges instead assumed the form of disgruntled rank and file soldiers expressing their dissatisfaction with their conditions of service. Why were generals no longer such a threat? A major part of the answer must surely be that sixth century emperors took care to appoint to military commands a significant number of individuals who were either related to them or were otherwise trusted associates. Anastasius’ nephews Hypatius and Pompeius both held military commands during his reign; Germanus, nephew of Justin I, and his son Justin (not the later Justin II), were generals under Justinian, as was Sittas, husband of the empress Theodora’s sister; two of Justin II’s generals, Marcian and Justinian, were also relatives of the emperor, as were the commanders Peter (brother) and Philippicus (brother-in-law) of the emperorMaurice. Justinian’s major reorganization of the eastern military command in 528, reducing the remit of the master of the soldiers in the east (magister militum per Orientem) by creating a separate Armenian command in the north with equal status, may also be significant in this respect; while no doubt serving an eminently practical purpose, it may also have been a decision taken with an eye to its political advantages – to curtail the potential power available to holders of this geographically extensive command and perhaps to encourage some distractive rivalry with his Armenian counterpart.

The sixth-century general in the best position to have challenged for the throne was Belisarius, and it is worth giving some consideration as to why he did never did so. That Justinian came to regard him as a threat is clear. Although Belisarius did not enjoy uninterrupted success on the battlefield throughout his career, his remarkably speedy capture of Carthage and destruction of Vandal rule in north Africa in 533–4 with comparatively small forces, against expectations informed by painful memories of the emperor Leo’s disastrous Vandal expedition in 468, ensured his reputation as a general and earned him enormous and enduring kudos in Constantinople. Justinian was already greatly indebted to Belisarius since the latter had played an important role in January 532 in suppressing the so-called Nika riot in Constantinople which had threatened an early end to Justinian’s reign, but he was also alive to the danger to his own position posed by Belisarius’ African success. In the immediate circumstances a careful balancing act was required. Belisarius was awarded the consulship for 53578 and was allowed a triumphal procession through the streets of Constantinople, albeit with important modifications of the traditional format designed to ensure that Justinian was not eclipsed: unlike Roman generals of old who were borne along in a chariot,Belisarius proceeded on foot and he joined the vanquished Vandal king Gelimer in prostrating himself before the emperor in the hippodrome. However, Belisarius’ distribution of gold and other Vandal booty to the public on ceremonial occasions during his year as consul (Procop. Wars 4.9.15–16, 5.5.18–19) clearly alarmed Justinian, whose subsequent restrictions on the consular distribution of gold have been seen plausibly as a reflection of his worries about Belisarius’ popularity. Also telling is Justinian’s reaction when Belisarius returned to Constantinople in 540 with the captured Gothic king Wittigis in tow and the war in Italy apparently also brought to a successful conclusion:

When he received the wealth of Theoderic [the most famous Gothic king], a notable sight in itself, Justinian merely laid it out for the senators to view privately in the palace, since he was jealous of the magnitude and splendour of the achievement. He did not bring it out before the people, nor did he grant Belisarius the customary triumph, as he had done when he returned from his victory over Gelimer and the Vandals. Nevertheless, the name of Belisarius was on everyone’s lips . . . The inhabitants of Constantinople took delight in watching Belisarius as he came out of his house each day and proceeded to the city centre or as he returned to his house, and no-one could get enough of this sight. For his progress resembled a crowded festival procession, since he was always escorted by a large number of Vandals, as well as Goths and Moors. (Procop. Wars 7.1.3–6 (Loeb trans. with revisions))

It is of course possible that Procopius deliberately overdrew the extent to which Belisarius experienced apparent ingratitude at the hands of Justinian as part of a polemic against the latter, but even if so, the question must still stand as to why Belisarius did not capitalize on his popularity and attempt to seize power. A range of possible factors may have played a part in strengthening his resolve not to act against Justinian: recollection of their common, humble Balkan background; residual gratitude for Justinian’s early advancement of his career; the close friendship between their wives Antonina and Theodora; the prestige which he continued to enjoy despite Justinian’s best efforts to limit his opportunities to be in the limelight; recognition that his popularity had alienated the support of other powerful individuals which would have been necessary to the success of any attempt on the throne.

As already noted, the main source of military challenge to emperors in the sixth century was from the rank and file of the army. Although there are some indications of mutinous behaviour in army units during the late fifth century, it is during the sixth century that there are well-documented cases. A combination of specific circumstances arising from the reconquest of north Africa from the Vandals in 533–4 spawned a mutiny by a significant proportion of troops stationed there in 536–7. Many of these soldiers married Vandal women and duly took offence when the government claimed Vandal land for itself and discriminated against Vandals who persisted in adhering to heterodox Arian Christianity. Belisarius returned from Sicily and was able to defuse some of this discontent through his personal popularity and judicious distribution of largesse, but it took military action by another general to suppress hardliners. Discontent among the troops in north Africa, however, rumbled on during the 540s, fuelled now by delays in receipt of pay. This too was the reason given for the decision of the garrison at Beroea inMesopotamia to surrender to the Persians in 540 (Procop. Wars 2.7.37), and it was also the cause of problems on the eastern frontier in the 570s (Men. Prot. fr. 18.6; Joh. Eph. Hist. eccl. 6.28). Reduction of pay by one quarter was one of the stimuli to the serious revolt of troops at Monocarton on the eastern frontier in 588, in addition to the replacement of one general by another less popular one.85 There was also unrest among the troops on the lowerDanube in the mid-590s when the emperorMaurice tried to introduce changes in military pay: it seems he wanted to replace the cash allowances which soldiers received for clothing and equipment with distributions of the actual articles; ‘the soldiers, who naturally preferred not to spend their full allowances on equipment, objected and it is likely that the attempt was abandoned’.

The fact remains, however, that these instances of unrest during the sixth century were localized, mostly distant from the capital, and sporadic.