The military treatise of Jiao Yu and Liu Ji went into a great amount of detail on the gunpowder weapons of their time. The fire lance and fire tube (i.e. a combination of a firearm and flamethrower) came in many different versions and were styled with many different names by the time Jiao Yu edited the Huolongjing. The earliest of these were made of bamboo tubes, although the earliest transition to metal was made in the 12th century. Others, according to description and illustrated pictures of the Huolongjing, emitted arrows called the ‘lotus bunch’ accompanied by a fiery blast. Some of these low–nitrate gunpowder flamethrowers used poisonous mixtures, including arsenious oxide, and would blast a spray of porcelain bits as shrapnel. The earliest depiction of a fire lance is dated c. 950 AD, a Chinese painting on a silk banner found at the Buddhist site of Dunhuang.

The idea of using fire as a propellant, whether of the spear itself or of smaller projectiles, developed out of the fire-spear and the fire-tube. A commensurate rise in nitrate content in the gunpowder seems to have accompanied these developments, though the evidence for a gradual rise is slight. The rocket and the fire-spear shared similar forms and nomenclature, leading Jixing Pan and others to confuse the two by reading several ambiguous passages in grammatically valid, but erroneous, ways that set the invention of the rocket slightly earlier than the evidence warranted. Quite a number of earlier scholars were very concerned about the invention of the rocket, an idiosyncratic interest to be sure given that rockets were of very limited value in warfare in pre-modern times. The fire-spear, by contrast, was a far more important device, since it was the basis of not only rockets, but also the true gun. Accordingly, I will first discuss the fire-spear and the fire-tube, before turning, briefly, to the rocket in the section that follows.

The fire-spear (or fire-lance as Needham would have it) first appears in representation in a Buddhist wall painting at Dunhuang dated to the mid-tenth century. A demon in military dress is attempting to distract the meditating Buddha by directing a jet of flame erupting from a tube attached to a pole. This early evidence for the weapon is not followed by other mentions until 1132, at the siege of De’an. Needham may well be correct in suggesting that fire-spears were not produced in sufficient quantities to warrant mention in texts like the Complete Essentials from the Military Classics, but the lacuna is nonetheless startling. Indeed, the device pictured seems more like a fire-tube (huotong), which I will discuss below, than a fire-spear.

A more conservative reading of the evidence might be that the firespear had not progressed beyond the experimental stage when the Complete Essentials from the Military Classics was compiled between 1040 and 1044. The device held by the demon in the Dunhuang painting is somewhat different than the later fire-spear in that it is not a spear with a fire-projecting tube attached, but simply a short pole with an attached tube. The difference is significant because a spear with a limited duration flame-projector is still a weapon once the projector runs out of fuel.

By the time the fire-spear is mentioned in 1132, its existence requires no comment, since the author clearly assumed that his reader knew what it was. When the Jurchen Jin attacked the city of De’an, Chen Gui successfully held out for seventy days before finally managing to drive off the besiegers. Chen prepared his defenses:

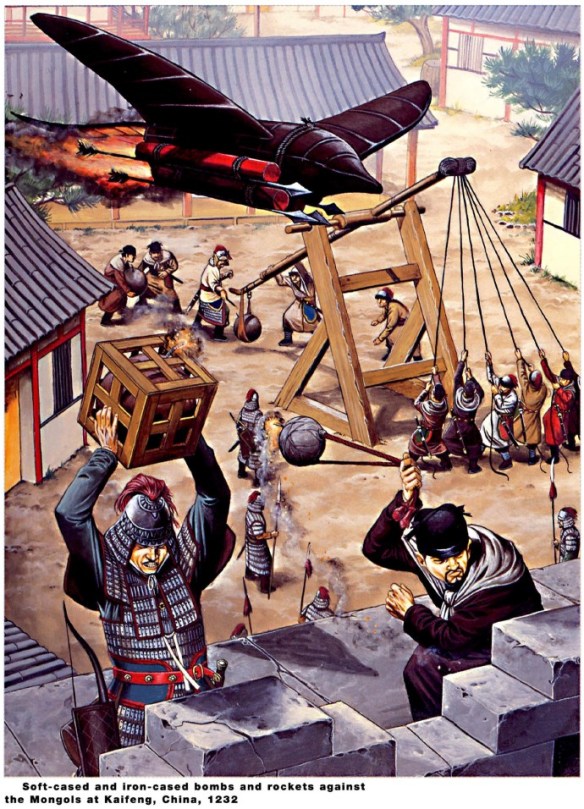

We also used bomb powder and long poles of bamboo to make more than twenty fire-spears. Also striking spears and swords with hooks at the ends, many of each. It took two men to handle each one. These things were got ready to use from the ramparts whenever the assault towers with the flying bridges approached the city.

Particularly in light of our previous discussion, it is important to note that the fire-spears were constructed on site, and that they used ‘‘bomb powder’’ and bamboo poles which required two men to manipulate. The exact descriptions used raise some very intriguing questions that we may not be able to resolve with the available information. Why is ‘‘bomb powder’’ (huopao yao) specified, rather than simply ‘‘gunpowder’’ (huoyao)? Presumably, ‘‘bomb powder’’ was different from other kinds of available gunpowder, though in what way we do not know. Alternatively, since Chen Gui was in some sense jury-rigging new weapons from the components of other weapons, in this case bombs, it may be that another name for gunpowder was ‘‘bomb powder.’’ Were bamboo poles used because they could function as the tubes containing the powder? This is likely, though later fire-spears used other material for the gunpowder tube and also had a spearhead for fighting. The items described in this passage are clearly specialized siege equipment, so the two-man fire-spear is idiosyncratic.

Fire-spears were decisive in breaking the siege of De’an, but these were different weapons than the two-man fire-spears. Li Heng, the Jurchen general, surrounded De’an, and started building flying bridges, filling in the moat, and making a great tumult near the city. Chen Gui led the defense, and was wounded in the foot by a catapult, but the siege really became critical as the food ran out. Chen maintained troop morale by using his personal funds to supply the troops. After seventy days, Li Heng sent a messenger indicating that he would raise the siege if they sent him a maiden. Chen refused, despite the entreaties of his commanders. Instead, he led a sally from the west gate with sixty men carrying fire-spears, and with the aid of a ‘‘fire ox’’ incinerated the Jurchen flying bridges. Li Heng lifted the siege and withdrew.

Chen Gui was obviously a commander of extraordinary ability and character, and the siege of De’an demonstrates the strengths and weaknesses of fire-spears. His earlier fire-spears were unable to destroy the Jurchen flying bridges from the ramparts of the city, though they did slow down the progress of the assault towers. The Jurchen besiegers were incapable of going through or over the walls, or through the gates, after more than two months of work. When Chen launched his attack, his most immediate threat was low supplies, though he realized by Li Heng’s odd offer to raise the siege in return for a token gift that the Jurchen army was in similarly bad straits. Morale had reached a critical point for both sides, and Chen’s destruction of the Jurchen siege equipment caused a complete collapse of Jurchen morale. Having suffered such a severe setback after such a long siege, it was impossible to contemplate continuing. What is so impressive about Chen Gui’s performance was not only that he timed his attack so well, but also that he could overcome the firespear’s lack of range and speed by waiting until his opponent’s vulnerable resources were close and fixed enough to destroy.

Even in Chen Gui’s remarkable feat the fire-spear was used as a device for destroying equipment, rather than as a hand-to-hand weapon. This is not surprising given the short, perhaps five minutes’, duration of the jet of flame. About a century later, at the siege of Guide in 1233, a Jurchen force armed with fire-spears ambushed a Mongol force. This time the Jurchens were fighting defensively against the Mongols, on small boats in the canals around the city. In the confined area of the canals, on boats at night, with the Mongols caught in front and rear, the fire-spears were devastating close-range weapons.