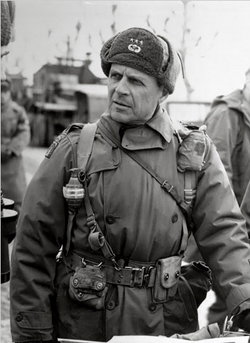

Gen. Matthew Ridgway, first succeeded Gen. Walton walker as commander of the U.S. Eighth Army and then succeeded Macarthur as commander of all the UN forces in the Korean War.

The two months that followed the launching of the Chinese offensive in November 1950 saw the longest retreat in U.S. military history. Before a secure defensive line was established (very near Osan, where Task Force Smith had first met the North Koreans the previous July), the U.S. Eighth Army had retreated 275 miles from the positions it held on the eve of the Chinese attack. North Korea was once again entirely under Communist control, and South Korea’s future looked grim. But with the arrival of a new commander, Gen. Matthew Ridgway, the Eighth Army regained its fighting spirit. And with the relief of General MacArthur as UN supreme commander, President Truman reestablished his control over foreign policy and military decision making in the Korean War. By the late spring of 1951 it was evident that the Communists would not be able to drive the UN forces out of South Korea. But no one knew how long it would be before a negotiated settlement could end the bloody stalemate on the battlefield.

As 1950 drew to an end, many U.S. troops were left demoralized by the ferocity of the Chinese attacks. “Bug-out fever” infected the UN forces. Pfc. James Cardinal of the 5th Cavalry wrote to his parents on January 7, 1951: “It looks like the beginning of the end. The Chinese are kicking hell out of the U.S. Army, and I think we are getting out, at least I hope so ... I don’t think we can hold the Chinks.” But even as Cardinal wrote his letter, the battlefield advantage in Korea began to shift to the UN.

Like MacArthur after Inchon, Chinese leaders deluded themselves into believing that a total, smashing victory would soon be theirs. Rather than halting their advance at the 38th parallel, they pressed on with their offensive. The United Nations made several proposals for a cease-fire to the Chinese. In January 1951, the United Nations proposed that an international conference be held after the establishment of a cease-fire in Korea; the conference could discuss such issues as Chinese membership in the United Nations and the future of Taiwan. (Chiang Kai-shek’s government still held the Chinese seat in the UN Security Council.) But Chinese Communist leaders were not interested. In the face of Communist recalcitrance, the United States was able to win a vote of the UN General Assembly on February 1, branding the Chinese aggressors for their intervention in Korea. Like the Americans in the fall of 1950, the Chinese leaders would pay heavily for their delusions in the spring of 1951.

Chinese advantages slipped away in January. They had suffered heavy losses in their offensive in December. And the farther south they advanced, the more difficult it was for them to keep their remaining troops supplied. UN forces, for their part, were now closer to their own supply depots and ports and fighting on more favorable terrain. Instead of having two armies separated by a vast expanse of roadless terrain, as they did in North Korea, the UN forces were united in a single force. (After the withdrawal from North Korea, x Corps was no longer treated as a separate army but came under the direction of the Eighth Army commander.) For the first time in the war, the United Nations could maintain a more or less continuous defensive line across the Korean Peninsula, shifting forces as needed by rail or road along the battlefront. And the Eighth Army gained a competent and charismatic leader who was determined to restore the morale and fighting capabilities of the hard-pressed U.S. soldiers.

Lt. Gen. Matthew Ridgway had a long and distinguished military career behind him when he arrived in Korea on December 26. The 56-year-old Ridgway had been serving in Washington, D.C., as the army’s deputy chief of staff for administration. But he was not a deskbound soldier. A graduate of West Point in 1917, he had been given command of the 82nd Airborne Division in World War II and had parachuted with his men behind enemy lines in the invasion of Sicily in 1943 and the invasion of Normandy in 1944. Ridgway had the respect of the Joint Chiefs of Staff in Washington and of General MacArthur. Truman and the Joint Chiefs expected that, unlike his predecessor, General Walker, Ridgway would be able to play a more independent role in shaping Korean strategy. When Ridgway met with MacArthur in Tokyo on December 26, MacArthur told him, “The Eighth Army is yours, Matt. Do what you think best.”

Ridgway had only just arrived in Korea when the Chinese launched their Third Phase Offensive on New Year’s Eve. The Eighth Army, which had taken up positions near the 38th parallel, was given another battering. The Chinese exploited the weakness of the South Korean units, who broke and ran from the Communists as they had the previous June. Ridgway drove north of Seoul on New Year’s Day and found “ROK soldiers by the truckloads” retreating, “without order, without arms, without leaders . . . They had thrown their rifles and pistols away.” By January 3, Ridgway had no choice but to order the evacuation of Seoul, the second time in the war it would be lost to the Communists. Inchon, the site of MacArthur’s triumphant amphibious landing the previous September, was abandoned on January 5. The Eighth Army fell back to the Kum River, 35 miles south of Seoul. Although no one knew it at the time, this would be the farthest south the UN forces would retreat for the remainder of the Korean War.

The Chinese offensive petered out after the first week in January, as their supply lines were stretched too thin. And with every passing week, they faced a more formidable foe. Unlike the retreat from North Korea in December, the Americans were not “bugging out” this time. They retreated in good order and then turned and fought when they reached strong defensive positions. Much of the credit for the change was owed to General Ridgway. He instilled in his men a new aggressiveness. Capturing territory, he told them, was not going to win or lose the war; instead, their goal should be to kill as many of the enemy as possible. Ridgway was soon a familiar figure along the front lines in Korea, famed for grenades he wore strapped on his combat jacket. The trouble with the Eighth Army, he told his officers, was that it had been road-bound; the Chinese had controlled the hills and were pounding U.S. truck convoys at will. U.S. soldiers had to get out of trucks and jeeps and up into the hills on foot, if they wanted to win the war. Army officers who would not lead by example, and take some risks, were sent packing back to the United States. Ridgway himself probably took more risks than was wise for a commanding general. He flew reconnaissance missions in a light observation plane over enemy territory, scouting out the possibilities for offensive action.

Under Ridgway’s command, the Eighth Army took other steps to improve the morale of its soldiers. A rest and recuperation (R&R) program was set up, so that soldiers who had spent months on the front line could spend five days’ leave enjoying the comforts available in Tokyo. The Mobile Army Surgical Hospitals (MASH), designed to provide high-quality emergency medical care to wounded soldiers, were upgraded. Wounded soldiers, evacuated from the front by helicopter, knew that their chances of survival were good if they could reach a MASH unit. (The MASH units would later become famous, thanks to the 1970 movie and 1970s television show M*A*S*H.) And in a war where sudden surprise attacks were always a danger, and where becoming a prisoner of war could be a fate worse than death, Ridgway promised that units cut off by the enemy would not be abandoned without every possible effort being made to come to their rescue.

General Macarthur is seen here riding in a jeep during one of his occasional inspection tours of the troops in Korea prior to his dismissal from command in April 1951.

In Tokyo, General MacArthur grew jealous of Ridgway’s successes, especially since they undermined his call for an all-out attack against the Chinese mainland. With his usual gift for showmanship, MacArthur showed up in Korea on February 20, announcing to newspaper reporters, “I have just ordered a resumption of the offensive.” In fact, Ridgway had drawn up plans for a new offensive called Operation Killer, scheduled to begin February 21, without any aid from MacArthur. MacArthur’s shameless grab for publicity endangered the lives of U.S. soldiers by notifying the Chinese of the impending attack. Operation Killer and both Operation Ripper and Operation Rugged, which followed in March, were nonetheless great successes. The UN forces pushed the Chinese back across the Han River. On March 15, the Chinese abandoned Seoul (the fourth and last time the devastated city would change hands during the war). By early April, UN forces once again held territory north of the 38th parallel.

Despite these reverses, the Chinese were by no means defeated. They had kept their main units a jump ahead of the UN offensive. UN forces were slowed down in their advance by the rain and mud, which came in the spring. And the Chinese had nearly inexhaustible supplies of manpower to draw upon. The Chinese armies regrouped north of the 38th parallel. Reinforcements flowed south across the Yalu. By the spring of 1951 the Communist armies, including both the Chinese and North Koreans, included roughly 700,000 men, arrayed against UN ground forces of only 420,000.