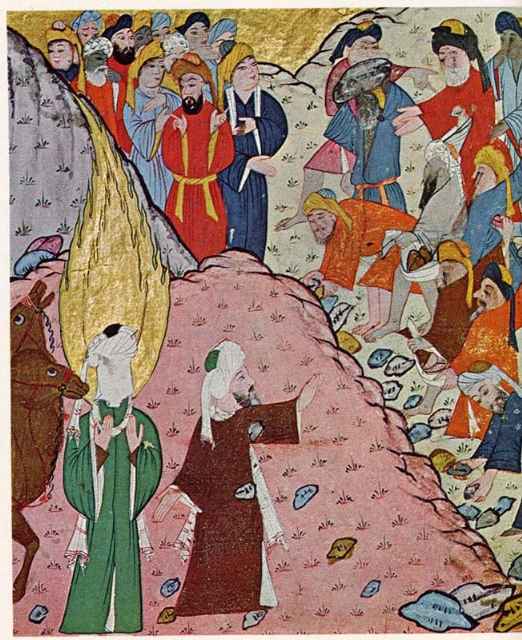

An imagining of Abu Bakr stopping the Meccan Mob, in a Turkish miniature from the 16th century C.E.

When Muhammad died, there was a moment of confusion among his followers. One of their leaders, Abu Bakr, proclaimed to the community: ‘O men, if you worship Muhammad, Muhammad is dead; if you worship God, God is alive.’ Beneath God there was still a role to be filled: that of arbiter of disputes and maker of decisions within the community. There were three main groups among the followers of Muhammad: the early companions who had made the hijra with him, a group linked by intermarriage; the prominent men of Madina who had made the compact with him there; and the members of the leading Meccan families, mainly of recent conversion. At a meeting of close associates and leaders, it was one of the first group who was chosen as the Prophet’s successor (khalifa, hence the word ‘caliph’): Abu Bakr, a follower of the first hour, whose daughter ‘A’isha was wife to the Prophet.

The caliph was not a prophet. Leader of the community, but not in any sense a messenger of God, he could not claim to be the spokesman of continuing revelations; but an aura of holiness and divine choice still lingered around the person and office of the early caliphs, and they did claim to have some kind of religious authority. Abu Bakr and his successors soon found themselves called upon to exercise leadership over a wider range than the Prophet. There was a universalism implicit in Muhammad’s teaching and actions: he claimed universal authority, the haram which he established had no natural limits; in his last years military expeditions had been sent against the Byzantine frontier lands, and he is supposed to have sent emissaries to the rulers of the great states, calling on them to acknowledge his message. When he died, the alliances he had made with tribal chiefs threatened to dissolve; some of them now rejected his prophetic claims, or at least the political control of Madina. Faced with this challenge, the community under Abu Bakr affirmed its authority by military action (the ‘wars of the ridda’); in the process an army was created, and the momentum of action carried it into the frontier regions of the great empires and then, as resistance proved weak, into their hearts. By the end of the reign of the second caliph, ‘Umar ibn al-Khattab (634–44), the whole of Arabia, part of the Sasanian Empire, and the Syrian and Egyptian provinces of the Byzantine Empire had been conquered; the rest of the Sasanian lands were occupied soon afterwards.

In the space of a few years, then, the political frontiers of the Near East had been changed and the centre of political life had moved from the rich and populous lands of the Fertile Crescent to a small town lying on the edge of the world of high culture and wealth. The change was so sudden and unexpected that it needs explanation. Evidence uncovered by archaeologists indicates that the prosperity and strength of the Mediterranean world were in decline because of barbarian invasions, failure to maintain terraces and other agricultural works, and the shrinking of the urban market. Both Byzantine and Sasanian Empires had been weakened by epidemics of plague and long wars; the hold of the Byzantines over Syria had been restored only after the defeat of the Sasanians in 629, and was still tenuous. The Arabs who invaded the two empires were not a tribal horde but an organized force, some of whose members had acquired military skill and experience in the service of the empires or in the fighting after the death of the Prophet. The use of camel transport gave them an advantage in campaigns fought over wide areas; the prospect of land and wealth created a coalition of interests among them; and the fervour of conviction gave some of them a different kind of strength.

Perhaps, however, another kind of explanation can be given for the acceptance of Arab rule by the population of the conquered countries. To most of them it did not much matter whether they were ruled by Iranians, Greeks or Arabs. Government impinged for the most part on the life of cities and their immediate hinterlands; apart from officials and classes whose interests were linked with theirs, and apart from the hierarchies of some religious communities, city-dwellers might not care much who ruled them, provided they were secure, at peace and reasonably taxed. The people of the countryside and steppes lived under their own chiefs and in accordance with their own customs, and it made little difference to them who ruled the cities. For some, the replacement of Greeks and Iranians by Arabs even offered advantages. Those whose opposition to Byzantine rule was expressed in terms of religious dissidence might find it easier to live under a ruler who was impartial towards various Christian groups, particularly as the new faith, which had as yet no fully developed system of doctrine or law, may not have appeared alien to them. In those parts of Syria and Iraq already occupied by people of Arabian origin and language, it was easy for their leaders to transfer their loyalties from the emperors to the new Arab alliance, all the more so because the control over them previously held by the Lakhmids and Ghassanids, the Arab client-states of the two great empires, had disappeared.

As the conquered area expanded, the way in which it was ruled had to change. The conquerors exercised their authority from armed camps where the Arabian soldiers were placed. In Syria, these for the most part lay in the cities which already existed, but elsewhere new settlements were made: Basra and Kufa in Iraq, Fustat in Egypt (from which Cairo was later to grow), others on the north-eastern frontier in Khurasan. Being centres of power, these camps were poles of attraction for immigrants from Arabia and the conquered lands, and they grew into cities, with the governor’s palace and the place of public assembly, the mosque, at the centre.

In Madina and the new camp-cities linked to it by inland routes, power was in the hands of a new ruling group. Some of its members were Companions of the Prophet, early and devoted followers, but a large element came from the Meccan families with their military and political skills, and from similar families in the nearby town of Ta’if. As the conquests continued others came from the leading families of pastoral tribes, even those who had tried to throw off the rule of Madina after the Prophet’s death. To some extent the different groups tended to mingle with each other. The Caliph ‘Umar created a system of stipends for those who had fought in the cause of Islam, regulated according to priority of conversion and service, and this reinforced the cohesion of the ruling élite, or at least their separation from those they ruled; between the newly wealthy members of the élite and the poorer people there were signs of tension from early times.

In spite of its ultimate cohesion, the group was split by personal and factional differences. The early Companions of the Prophet looked askance at later converts who had obtained power; claims of early conversion and close links with Muhammad might clash with claims to the nobility of ancient and honourable ancestry. The people of Madina saw power being drawn northwards towards the richer and more populous lands of Syria and Iraq, where governors tried to make their power more independent.

Such tensions came to the surface in the reign of the third caliph, ‘Uthman ibn ‘Affan (644–56). He was chosen by a small group of members of Quraysh, after ‘Umar had been assassinated for private vengeance. He seemed to offer the hope of reconciling factions, for he belonged to the inner core of Quraysh but had been an early convert. In the event, however, his policy was one of appointing members of his own clan as provincial governors, and this aroused opposition, both in Madina from the sons of Companions and from the Prophet’s wife ‘A’isha, and in Kufa and Fustat; some of the tribes resented the domination of men from Mecca. A movement of unrest in Madina, supported by soldiers from Egypt, led to ‘Uthman’s murder in 656.

This opened the first period of civil war in the community. The claimant to the succession, ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib (656–61), was of Quraysh, an early convert, a cousin of Muhammad and married to his daughter Fatima. He found himself faced with a double opposition. The kin of ‘Uthman were against him, but so were others who disputed the validity of his election. The struggle for power in Madina was carried into the camp-cities. ‘Ali established himself as caliph in Kufa, the dissidents in Basra; he defeated them, but was now faced with a new challenge from Syria, where the governor, Mu‘awiya ibn Abi Sufyan, was a close kinsman of ‘Uthman. The two forces met at Siffin on the upper Euphrates, but after fighting for a time they agreed on arbitration by delegates chosen from the two sides. When ‘Ali agreed to this, some of his supporters abandoned him, for they were not willing to accept compromise and submit the Will of God, as they saw it, to human judgement; the honour due to early conversion to Islam was at stake. In the months of discussion between the arbiters, ‘Ali’s alliance grew weaker, and finally he was assassinated in his own city of Kufa. Mu‘awiya proclaimed himself caliph and ‘Ali’s elder son, Hasan, acquiesced in it.

THE CALIPHATE OF DAMASCUS

The coming to power by Mu‘awiya (661–80) has always been regarded as marking the end of one phase and the beginning of another. The first four caliphs, from Abu Bakr to ‘Ali, are known to the majority of Muslims as the Rashidun or ‘Rightly Guided’. Later caliphs were seen in a rather different light. First of all, from now on the position was virtually hereditary. Although some idea of choice, or at least formal recognition, by the leaders of the community remained, in fact from this time power was in the hands of a family, known from an ancestor, Umayya, as that of the Umayyads. When Mu‘awiya died, he was succeeded by his son, who was followed briefly by his own son; after that there was a second period of civil war and the throne passed to another branch of the family.

The change was more than one of rulers. The capital of the empire moved to Damascus, a city lying in a countryside able to provide the surplus needed to maintain a court, government and army, and in a region from which the eastern Mediterranean coastlands and the land to the east of them could be controlled more easily than from Madina. This was the more important because the caliph’s rule was still expanding. Muslim forces advanced across the Maghrib. They established their first important base at Qayrawan in the former Roman province of Africa (Ifriqiya, the present day Tunisia); from there they moved westwards, reached the Atlantic coast of Morocco by the end of the seventh century and crossed into Spain soon afterwards; at the other extreme, the land beyond Khurasan reaching as far as the Oxus valley was conquered and the first Muslim advances were made into north-western India.

Such an empire demanded a new style of government. An opinion widespread in later generations, when the Umayyads had been replaced by a dynasty hostile to them, held that they had introduced a government directed towards worldly ends determined by self-interest in place of that of the earlier caliphs who had been devoted to the well-being of religion. It would be fairer to say that the Umayyads found themselves faced with the problems of governing a great empire and therefore became involved in the compromises of power. Gradually, from being Arab chieftains, they formed a way of life patterned on that traditional among rulers of the Near East, receiving their guests or subjects in accordance with the ceremonial usages of Byzantine emperor or Iranian king. The first Arabian armies were replaced by regular paid forces. A new ruling group was formed largely from army leaders or tribal chiefs; the leading families in Mecca and Madina ceased to be important because they were distant from the seat of power, and they tried more than once to revolt. The cities of Iraq too were of doubtful loyalty and had to be controlled by strong governors loyal to the caliph. The rulers were townspeople, committed to settled life and hostile to claims to power and leadership based upon tribal solidarity; ‘you are putting relationship before religion’, warned the first Umayyad governor of Iraq, and a successor, Hajjaj, dealt even more firmly with the tribal nobility and their followers.

Although armed power was in new hands, the financial administration continued as before, with secretaries drawn from the groups which had served previous rulers, using Greek in the west and Pahlavi in the east. From the 690s the language of administration was altered to Arabic, but this may not have marked a large change in personnel or methods; members of secretarial families who knew Arabic continued to work, and many became Muslims, particularly in Syria.

The new rulers established themselves firmly not only in the cities but in the Syrian countryside, on crown lands and land from which the owners had fled, particularly in the interior regions which lay open to the north Arabian steppe. They seem carefully to have maintained the systems of irrigation and cultivation which they found there, and the palaces and houses they built to serve as centres of economic control as well as hospitality were arranged and decorated in the style of the rulers they had replaced, with audience-halls and baths, mosaic floors, sculptured doorways and ceilings.

In this and other ways the Umayyads may seem to have resembled the barbarian kings of the western Roman Empire, uneasy settlers in an alien world whose life continued beneath the protection of their power. There was a difference, however. The rulers in the west had brought little of their own which could stand against the force of the Latin Christian civilization into which they were drawn. The Arab ruling group brought something with them which they were to retain amidst the high culture of the Near East, and which, modified and developed by that culture, would provide an idiom through which it could henceforth express itself: belief in a revelation sent by God to the Prophet Muhammad in the Arabic language.

The first clear assertion of the permanence and distinctiveness of the new order came in the 690s, in the reign of the Caliph ‘Abd al-Malik (685–705). At the same time as Arabic was introduced for purposes of administration, a new style of coinage was brought in, and this was significant, since coins are symbols of power and identity. In place of the coins showing human figures, which had been taken over from the Sasanians or struck by the Umayyads in Damascus, new ones were minted carrying words alone, proclaiming in Arabic the oneness of God and the truth of the religion brought by His messenger.

More important still was the creation of great monumental buildings, themselves a public statement that the revelation given through Muhammad to mankind was the final and most complete one, and that its kingdom would last for ever.

The first places for communal prayer (masjid, hence the English word ‘mosque’, perhaps through Spanish mezquita) were also used for assemblies of the whole community to transact public business. They had no marks to distinguish them clearly from other kinds of building: some were in fact older buildings taken over for the purpose, while others were new ones in the centres of Muslim settlement. The holy places of the Jews and Christians still had a hold over the imagination of the new rulers: ‘Umar had visited Jerusalem after it was captured, and Mu‘awiya was proclaimed caliph there. Then in the 690s there was erected the first great building which clearly asserted that Islam was distinct and would endure. This was the Dome of the Rock, built on the site of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem, now turned into a Muslim haram; it was to be an ambulatory for pilgrims around the rock where, according to Rabbinic tradition, God had called upon Abraham to sacrifice Isaac. The building of the Dome in this place has been convincingly interpreted as a symbolic act placing Islam in the lineage of Abraham and dissociating it from Judaism and Christianity. The inscriptions around the interior, the earliest known physical embodiment of texts from the Qur’an, proclaim the greatness of God, ‘the Mighty, the Wise’, declare that ‘God and His angels bless the Prophet’, and call upon Christians to recognize Jesus as an apostle of God, His word and spirit, but not His son.1

A little later there began to be built a series of great mosques designed to meet the needs of ritual prayer: in Damascus and Aleppo, Madina and Jerusalem, and later in Qayrawan, the first Arab centre in the Maghrib, and in Cordoba, the Arab capital in Spain. All show the same basic design. An open courtyard leads to a covered space so shaped that long lines of worshippers led by a prayer-leader (imam) can face in the direction of Mecca. A niche (mihrab) marks the wall to which they face, and near it is a pulpit (minbar) where a sermon is preached during the noon prayer on Friday. Attached to the building or lying close to it is the minaret from which the muezzin (mu’adhdhin) calls the faithful to prayer at the appointed times.

Such buildings were signs not only of a new power but of the growth of a new and distinct community. From being the faith of a ruling group, acceptance of the revelation given to Muhammad gradually spread. We know little of the process, and can only speculate on the course it took. Arabs already living in the Syrian and Iraqi countryside could easily make the act of acceptance out of solidarity with the new rulers (although part of one tribe, that of Ghassan, did not). Officials working for the new rulers might accept their faith out of self-interest or a natural attraction towards power; so too might prisoners captured in the wars of conquest, or Sasanian soldiers who had joined the Arabs. Immigrants into the new cities might convert in order to avoid the special taxes paid by non-Muslims. Zoroastrians, adherents of the ancient Persian religion, may have found it easier to become Muslims than did Christians, because their organized Church had been weakened when Sasanian rule came to an end. Some Christians, however, touched by controversies about the nature of God and revelation, might be attracted by the simplicity of the early Muslim response to such questions, within what was broadly the same universe of thought. The absence of a Muslim Church or an elaborate ritual of conversion, the need only to use a few simple words, made acceptance an easy process. However simple it was, the act carried with it an implication: the acceptance of Arabic as the language in which revelation had been given, and this, together with the need to deal with Arab rulers, soldiers and landowners, could lead to its acceptance as the language of everyday life. Where Islam came, the Arabic language spread. This process, however, was still young; outside Arabia itself, the Umayyads ruled lands where most of the population were neither Muslims nor speakers of Arabic.

The growing size and strength of the Muslim community did not work in favour of the Umayyads. Their central region, Syria, was a weak link in the chain of countries being drawn into the empire. Unlike the new cities in Iran, Iraq and Africa, its cities had existed before Islam and had a life independent of their rulers. Its trade had been disrupted by its separation from Anatolia, which remained in Byzantine hands, across a new frontier often disturbed by war between Arabs and Byzantines.

The main strength of the Muslim community lay further east. The cities of Iraq were growing in size, as immigrants came in from Iran as well as the Arabian peninsula. They could draw on the wealth of the rich irrigated lands of southern Iraq, where some Arabs had installed themselves as landowners. The new cities were more fully Arab than those of Syria, and their life was enriched as members of the former Iranian ruling class were drawn in as officials and tax-collectors.

A similar process was taking place in Khurasan, in the far north-east of the empire. Lying as it did on the frontier of Islam’s expansion into central Asia, it had large garrisons. Its cultivable land and pastures also attracted Arab settlers. From an early time there was therefore a considerable Arab population, living side by side with the Iranians, whose old landed and ruling class kept their position. A kind of symbiosis was gradually taking place: as they ceased to be active fighters and settled in the countryside or in the towns – Nishapur, Balkh and Marv – Arabs were being drawn into Iranian society; Iranians were entering the ruling group.

The growth of the Muslim communities in the eastern cities and provinces created tensions. Personal ambitions, local grievances and party conflicts expressed themselves in more than one idiom, ethnic, tribal and religious, and from this distance it is hard to say how the lines of division were drawn.

There was, first of all, among converts to Islam, and the Iranians in particular, resentment against the fiscal and other privileges given to those of Arab origin, and this grew as the memory of the first conquests became weaker. Some of the converts attached themselves to Arab tribal leaders as ‘clients’ (mawali), but this did not erase the line between them and the Arabs.

Tensions also expressed themselves in terms of tribal difference and opposition. The armies coming from Arabia brought tribal loyalties with them, and in the new circumstances these could grow stronger. In the cities and other places of migration, groups claiming a common ancestor came together in closer quarters than in the Arabian steppe; powerful leaders claiming nobility of descent could attract more followers. The existence of a unified political structure enabled leaders and tribes to link up with each other over wide areas and at times gave them common interests. The struggle for control of the central government could make use of tribal names and the loyalties they expressed. One branch of the Umayyads was linked by marriage with the Banu Kalb, who had already settled in Syria before the conquest; in the struggle for the succession after the death of Mu‘awiya’s son, a non-Umayyad claimant was supported by another group of tribes. At moments some common interest could give substance to the idea of an origin shared by all tribes claiming to come from central Arabia or from the south. (Their names, Qays and Yemen, were to linger as symbols of local conflict in some parts of Syria until the present century.)

Of more lasting importance were the disputes about the succession to the caliphate and the nature of authority in the Muslim community. Against the claims of Mu‘awiya and his family there stood two groups, although each was so amorphous that it would be better to describe them as tendencies. First were the various groups called Kharijis. The earliest had been those who had withdrawn their support from ‘Ali when he had agreed to arbitration on the day of Siffin. They had been crushed, but later movements used the same name, particularly in regions under the control of Basra. In opposition to the claims of tribal leaders, they maintained that there was no precedence in Islam except that of virtue. Only the virtuous Muslim should rule as imam, and if he went astray obedience should be withdrawn from him; ‘Uthman, who had given priority to the claims of family, and ‘Ali, who had agreed to compromise on a question of principle, had both been at fault. Not all of them drew the same conclusions from this: some acquiesced for the time in Umayyad rule, some revolted against it, and some held that true believers should try to create a virtuous society by a new hijra in a distant place.

The other group was that which supported the claims of the family of the Prophet to rule. This was an idea which could take many different forms. The most important in the long run was that which regarded ‘Ali and a line of his descendants as legitimate heads of the community or imams. Around this idea there clustered others, some of them brought in from the religious cultures of the conquered countries. ‘Ali and his heirs were thought of as having received by transmission from Muhammad some special quality of soul and knowledge of the inner meaning of the Qur’an, even as being in some sense more than human; one of them would arise to inaugurate the rule of justice. This expectation of the coming of a mahdi, ‘him who is guided’, arose early in the history of Islam. In 680 the second son of ‘Ali, Husayn, moved into Iraq with a small party of kinsmen and retainers, hoping to find support in and around Kufa. He was killed in a fight at Karbala in Iraq, and his death was to give the strength of remembered martyrdom to the partisans of ‘Ali (the shi‘at ‘Ali or Shi‘is). A few years later there was another revolt in favour of Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyya, who was also ‘Ali’s son, although not by Fatima.

During the first decades of the eighth century, Umayyad rulers made a series of attempts to deal with movements of opposition expressed in these various ways, and with the inherent difficulties of ruling an empire so vast and heterogeneous. They were able to strengthen the fiscal and military bases of their rule, and for a time had to face few major revolts. Then in the 740s their power suddenly collapsed in the face of yet another civil war and a coalition of movements with different aims but united by a common opposition to them. These movements were stronger in the eastern than the western parts of the empire, and particularly strong in Khurasan, among some of the Arab settler groups who were on the way to being assimilated into local Iranian society, as well as among the Iranian ‘clients’. There as elsewhere there was a Shi‘i sentiment widely diffused but having no organization.

More effective leadership came from another branch of the family of the Prophet, the descendants of his uncle ‘Abbas. Claiming that the son of Muhammad ibn al-Hanafiyya had passed on to them his right of succession, from their residences on the edge of the Syrian desert they created an organization with its centre at Kufa. As their emissary to Khurasan they sent a man of obscure origin, probably of an Iranian family, Abu Muslim. He was able to form an army and a coalition from dissident elements, Arab and other, and to come out in revolt under the black banner which was to be the symbol of the movement, and in the name of a member of the Prophet’s family; no member was specifically mentioned, thus widening support for the movement. From Khurasan the army moved westwards, the Umayyads were defeated in a number of battles in 749–50, and the last caliph of the house, Marwan II, was pursued to Egypt and killed. In the meantime, the unnamed leader was proclaimed in Kufa; he was Abu’l-‘Abbas, a descendant not of ‘Ali but of ‘Abbas.

The historian al-Tabari (839–923) has described how the announcement was made. Abu’l-‘Abbas’s brother Dawud stood on the pulpit steps of the mosque in Kufa and addressed the faithful:

Praise be to God, with gratitude, gratitude, and yet more gratitude! Praise to him who has caused our enemies to perish and brought to us our inheritance from Muhammad our Prophet, God’s blessing and peace be upon him! O ye people, now are the dark nights of the world put to flight, its covering lifted, now light breaks in the earth and the heavens, and the sun rises from the springs of day while the moon ascends from its appointed place. He who fashioned the bow takes it up, and the arrow returns to him who shot it. Right has come back to where it originated, among the people of the house of your Prophet, people of compassion and mercy for you and sympathy toward you … God has let you behold what you were awaiting and looking forward to. He has made manifest among you a caliph of the clan of Hashim, brightening thereby your faces and making you to prevail over the army of Syria, and transferring the sovereignty and the glory of Islam to you … Has any successor to God’s messenger ascended this your minbar save the Commander of the Faithful ‘Ali ibn Abi Talib and the Commander of the Faithful ‘Abd Allah ibn Muhammad? – and he gestured with his hand toward Abu’l-‘Abbas.