On 3 November 1917 the AOK had weighed its options for the coming year in the wake of the Russian collapse. It was not optimistic. In the east the Monarchy maintained 32 infantry divisions and 12 cavalry along a 325-mile front; the Germans 92 divisions on their 775-mile line. In Italy the Central Powers posted 37 Austrian divisions and eight German along a 290-mile front. Density ratios were one division per 8 miles in the east; and one per 6 miles in Italy. Most divisions were down to between 5000 and 8000 men. Dismounted cavalry divisions were at half strength. One-third of all artillery batteries lacked sufficient horses. Karl’s staff posed the rhetorical question whether the k. u. k. Army could undertake offensive actions in 1918 and came to a quick and unanimous decision: `No, not by itself!’ At best, given immediate reinforcements of five or six divisions, the Army hoped to hold current lines. It ruled out even minor counter-offensives.

Conrad was of different opinion and decided once more to play va banque, victory or demise. On 30 January 1918 he sent Baden the first of numerous proposals for a major offensive out of the Sieben Gemeinden around Asiago and across the Etsch and the Piave rivers on to the Venetian plain, taking the main Italian Army in the flank. Eight days later, after receiving only a lukewarm reception for his plans from the AOK, the Field Marshal again proposed a thrust out of the Tyrolean Alps designed `vitally to hit’ the enemy’s principal supply routes. Baden again reacted sceptically. On 22 March Conrad sent in yet another plan for a Tyrolean offensive. The main attack this time was to be launched from both sides of the Brenta River towards Pasubio-Vicenza-Cornuda and conducted with 31 infantry divisions and 3 cavalry. Short of 15 infantry divisions and 2 cavalry, Conrad brazenly asked Arz von Straußenburg to supply the missing forces. The Chief of the General Staff, while paying lip service to this grand design (`I expect Italy’s military destruction’), worked behind the scenes to deny Conrad the forces necessary to mount the operation.

As so often in the past, Conrad once more chose not to let reality interfere with his strategic designs. He ignored both the difficulty of the heavily-wooded and mountainous terrain and the `terrible condition’ of his own forces. Having devoured the abundant Italian food supplies captured after the Battle of Caporetto, daily rations were down to roughly 230 g of flour per man; some regiments received but 125 g of lumpy corn meal; and meat rations averaged 150 g. German deliveries of 30,000 tons of flour – against 35,000 cattle and 50,000 hogs from Hungary – alone allowed the AOK to contemplate an offensive. K. u. k. soldiers were so undernourished and badly trained that the Army fully expected loss rates of 5 per cent per month during `normal’ (holding) operations. In March Karl out of a sense of pity ordered soldiers in their early fifties home.

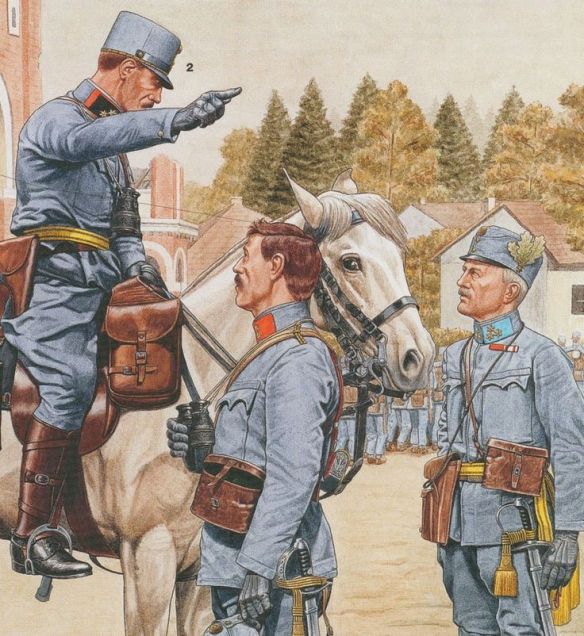

Nor were the necessary `machines of war’ available. The 70th Artillery Brigade, for example, reported that it was short of 150 men and 300 horses. The 51st and 64th brigades stated unequivocally that they were immobilized by the lack of draught animals: individual batteries were down to only three or five horses; one had but a single animal to pull its guns. And while the Army worked feverishly at its training schools at Brixen and Passariano to develop new manuals for the attack, these were not published until June.

Most importantly, Austro-Hungarian military leaders from the Kaiser on down ignored the visible signs of rebellion among the troops especially in rear-echelon areas. Three weeks before the planned offensive in Venetia, War Minister Stöger-Steiner sent the Kaiser, the Ballhausplatz and all senior commanders a report on seven recent mutinies. On the night of 12-13 May, Slovenian reserves attached to the 17th Infantry Regiment at Judenburg in Styria had followed several non-commissioned officers `like wild hordes’ and for 6 hours plundered cafés, pubs, restaurants, merchant stores, silver and gold smiths and a tobacco warehouse. The troops destroyed the local barracks and officers’ mess, tore up railroad tracks and riddled the train station and several cars with bullets, killing six soldiers and one civilian and injuring 17 others. Local machine-gun units were helpless against the marauders as they had no ammunition. Most of the mutineers disappeared into the nearby forests with thousands of pounds of flour and sugar taken from freight cars. Eventually, loyal troops had to be brought in from Graz to put down the mutiny. Several rebels were shot; six ringleaders were summarily executed; faced courts-martial; and most of the remaining 1200 eventually were rounded up. Two days later, some of the mutineers from Judenburg incited the 7th Jäger battalion at Murau to riot. Loyal units once more suppressed the rebellion and executed one of its leaders. A third outbreak, again marked by looting and plundering, affected the 80th Infantry Division at Rimaszombat. The fourth case, involved the 58th Infantry Regiment at Lublin.

On 20 May reserves of the 6th Infantry Division at Pécs rioted and killed two officers. It took loyal units 2 weeks to round up the mutineers. Four ringleaders were summarily executed while courts-martial awaited the remainder. In one of the largest uprisings, about 500 Czech soldiers of the 7th Reserve Rifle Battalion at Rumburg and Haida in northern Bohemia rioted for days; courts-martial awaited the ringleaders. Finally, several reserve units of the 97th Infantry Regiment (Slovenian) at Radkersburg rebelled on 23-24 May, but their leaders were quickly arrested and placed before military tribunals.

Reserve units had instigated each of the revolts. Most had involved some of the 500,000 former Russian POWs detailed to rear-echelon formations. Almost all of the mutineers – save the ringleaders – were disarmed and sent to the front. Not even the classic Habsburg practice of setting one ethnic group against another – in this case Hungarian against Czech troops, and Czech and Bosnian against Hungarian – proved effective. The Foreign Ministry wryly noted that news of the mutinies had been leaked to the German press, and from there had found its way to the Entente. Could Conrad possibly have missed it?

In fact, Stöger-Steiner had failed to mention two other cases of insurrection. A bloody mutiny by the 71st Infantry Regiment at Kragujevac in Serbia was suppressed only with the aid of artillery and machine guns at the cost of 16 soldiers killed and 40 wounded. And most of the Polish Auxiliary Corps had run over to the Russians; the rest were disarmed and the Corps disbanded on 19 February. More than 4800 Poles taken into custody by military police were sent to the Italian front, where in April they rioted against further fighting. Laibach, Mostar and Przemyol also experienced military uprisings while the `green cadres’ continued to roam the countryside at will.

Yet the AOK, being without firm plans for 1918, was both embarrassed and paralysed by Conrad’s operational barrages. Whatever one might say of Conrad, he at least was consistent in demanding an assault against the Italians out of his native Tyrol. In contrast, Field Marshal Svetozar von Boroeviæ, recently given his own army group consisting of the erstwhile Isonzo Army and a new Sixth Army (the former German Fourteenth Army), had developed a `bunker mentality’. The Croat insisted on a defensive posture in Italy – especially when Vice Admiral Horthy denied his request for naval support. But, when pressed for an operations plan, Boroeviæ came out for a suicidal frontal assault from Oderzo across the Piave in the direction of Treviso. Boroeviæ had 14 divisions and wanted 23 or 24; Conrad had 16 and demanded 32. Neither apparently pondered on where they were going to get the 70 tons of food, 30 tons of ammunition and 30 tons of fodder and other supplies that each division needed – while standing still! Nor the 20,000 horses needed to haul the artillery. General Alfred von Waldstätten, Arz’s deputy, favoured a broad offensive designed to pinch both Italian flanks, but with the main assault coming in the centre. He expected nothing less than a total collapse of the Italian front.

On 11 April, after having sent the AOK yet another operations plan, Conrad was summoned by the Kaiser to Baden. He at once decided to force a decision. Karl, who had advanced in just over 2 years from major to four-star general and who fancied himself a military talent, revealed a glaring lack of strategic sense by decreeing that Boroeviæ and Conrad were to launch two separate pincer attacks with 23 divisions each, one across the Piave and the other out of the Tyrol. Karl thus ensured that neither attack would be decisive. The operations were codenamed `Albrecht’ (Boroeviæ) and `Radetzky’ (Conrad) in honour of the two great Habsburg captains. The offensive by four armies was to be the largest in the course of the war.

Conrad had pressed his operational studies on the AOK suspecting that Ludendorff desired an Austro-Hungarian `diversion’ in the south while the OHL orchestrated an offensive on the Western Front. But whatever leverage the Dual Monarchy might have derived from this was quickly lost early in April, when Foreign Minister Czernin blundered into reopening the so-called `Sixtus affair’ of the previous year. In an important address to the Vienna Municipal Council on 2 April, Czernin stated that the French had been prepared for peace negotiations in 1917, but that these had foundered on Premier Georges Clemenceau’s demand that Alsace-Lorraine be `returned’ to France. Czernin allowed that he had rejected the `Old Tiger’s’ demands out of loyalty to Berlin.

Clemenceau was hardly the man to stand for this gross distortion: on 12 April he had L’Illustration print Prince Sixtus’ letter in its entirety, thereby revealing to all the world Karl’s written acknowledgement of France’s `just claims’ to Alsace-Lorraine. Panicked by Czernin’s suicide threats should he not declare on his honour (and in writing) that he had never sent the letter via Sixtus, Karl worsened an already dreadful situation by stating that the `Sixtus letter’ was a forgery! He informed the German Ambassador, Wedel, that `he was as innocent as a newborn child’. Few believed him. There was talk in Vienna of a regency under either Archduke Friedrich or Archduke Eugen.

German leaders spoke openly of perfidy by the House of Habsburg, and made caustic references to Karl’s role as a `dual’ monarch. Habsburg Chief of the General Staff Arz von Straußenburg privately informed the Germans of his conviction that Karl had lied. Patriotic Austrians in the Tyrol detected the hand of the `Italian’ Empress Zita behind the affair, and as newfound `Bavarians’ mounted public demonstrations of loyalty to Germany. The Czechs, fearing that a separate peace could translate into a German occupation of Bohemia, likewise protested about the Kaiser’s diplomatic odyssey. Egged on by Zita, Karl forced a tearful Czernin to yield his post at the Ballhausplatz within 48 hours. Innsbruck and Salzburg were draped in black out of a sense of grief and shame. As his last act as foreign minister, Czernin fired off a communiqué stating that the `Sixtus letter’ was `fictitious from beginning to end’. Karl sought to save face with the Germans by blaming the affair on Czernin, and by assuring them that `his cannons’ would give the French the proper response along the Western Front. Clemenceau’s `Sixtus’ bombshell convinced the Allies, the Germans and the major ethnic groups in the Empire that the House of Habsburg could not be trusted. Karl’s word was worthless. Brokers in London noted that aristocratic clans such as the Counts Clam- Martinic, Clary and Czernin put their estates in Bohemia and Moravia on the market.

On 12 May Karl was forced to travel to German headquarters at Spa – the so-called pilgrimage to Canossa – to apologize for his actions. The Germans demanded nothing less than a binding political, military and economic alliance, thereby committing Vienna to what was now popularly called the `German course’. Specifically, Hindenburg inked an agreement with Arz von Straußenburg calling on both Empires to mobilize their entire peoples; every eligible male `must pass through the school of the Army’. Organization, training and deployment of troops were to be coordinated between Berlin and Vienna, and weapons and munitions standardized. Officers were to be exchanged regularly, rail networks expanded by common consent, and preparations for war `mutually arrived at’. No one asked why this had not been the case in 1914.

Weakened by Clemenceau’s revelations and recognizing the need to raise the Dual Monarchy’s fortunes, Karl, once back in Baden, yielded to Conrad’s operational bravado. The attack out of the Tyrol, originally scheduled for 28 May, was delayed 2 weeks due to transport difficulties. It also lost the element of surprise when deserters and intercepts of field telephones apprised the Italians, strengthened by five British and French divisions, of the impending assault. Snow in the mountains delayed supply: Conrad’s staff estimated that 2 million artillery rounds remained in depots on the opening day of the attack; and more than 50 batteries of artillery were still struggling to move up to the front. Artillery and infantry were short roughly 6000 horses, with the result that soldiers routinely spent 4-6 hours per day hauling supplies on their backs up steep mountain paths. Troops had barely half of the requisite 3-days’ provisions. And on 5 June French artillery severely pounded Conrad’s marshalling positions, destroying two artillery parks.

After almost a week of steady rain, Conrad’s Eleventh Army on 15 June 1918 attacked along a broad 50-mile front over the Tonale Pass between Astico and the Piave River. The artillery bombardment commenced at 3 a. m., and infantry stormed enemy positions four hours later. Conrad’s troops, like those of Napoleon Bonaparte in 1796, pressed forward in hopes of raiding bountiful Italian food depots and garnering bounty money – 50 Kronen for a French prisoner of war, 500 for an enemy aircraft downed by ground fire and 3000 for a hostile plane forced to land behind Austrian lines. 63 Conrad dreamed of entering Venice; Boroeviæ wanted to reach Padua. Conrad’s forces made some initial progress, but by late afternoon were repulsed by the stiff Anglo-French defence. Allied artillery tore up Conrad’s telegraph lines and completely overpowered his guns. By 16 June, the Eleventh Army was back in its original positions, low on food and ammunition, demoralized. It had lost more than 1000 officers and 45,000 men. The planned pincer envelopment of the Italians from the Tyrol and along the Adriatic Sea now gave way to the Battle of the Piave – a straight frontal assault across the river.

Field Marshal von Boroeviæ, attacking in the direction of Oderzo- Treviso, opened his offensive with a gas-shell attack in dense fog and smoke at 3 a. m. on 15 June. Much of his ammunition was defective. At 5:30 a. m. he ordered his infantry to cross the Piave, swelled to three times its normal level by the unending rains. The Sixth Army managed to establish a 15-milewide by 5-mile-deep bridgehead on the river, but then it was driven back by Entente troops. Allied air forces destroyed the Field Marshal’s pontoon bridges by 18 June. Boroeviæ’s pilots reported that their water-cooled machine guns froze at high altitudes and that hostile phosphoric bullets ignited their linen-covered craft: the Austrians lost 269 of 382 airplanes. Low on supplies and demoralized, Boroeviæ’s troops faced certain Allied counterattacks. Peter Fiala, an Austrian historian of the `June Offensive’, states that the evening of 15 June constituted the `Götterdämmerung of Austro-Hungarian strategy’. The following day, Colonel Ottokar Pflug of the logistics branch reported that the last 29 supply trains had been sent to the front. There would be no more.

Panic-stricken, Karl raced his special train first to Conrad’s headquarters to inquire into the demise of the Eleventh Army, and then towards the Piave to consult Boroeviæ. On 19 June the Kaiser discussed the military situation with the Croat. `General consternation’ was recorded on both sides. Karl pleaded with Boroeviæ: `Hold your positions. I beg you to do this in the name of the Monarchy.’ Boroeviæ reminded Karl that he had opposed Conrad’s frontal assault out of the Tyrol from the start with the query, `But one does not want to grab the bull by the horns?’ To which Karl lamely replied: `But Conrad wanted it.’ The next day, the Kaiser called off the attack. Boroeviæ’s forces were saved from annihilation only by General Armando Diaz’s failure to hurl his reserve of six Italian divisions against the Habsburg units struggling to recross the Piave. The field marshal’s baton that German officers had sent to reward Karl for a victorious Italian campaign remained in its case on the imperial train.

The aborted offensive had been bloody. In the 9 days between 15 and 25 June, the Austro-Hungarian Army lost 118,000 men, including 11,000 dead, 25,000 prisoners of war and 80,000 missing; Allied losses were set at 84,830 soldiers, including 8030 killed. Especially, the infantry had suffered terribly due to lusty sacrifice and lack of artillery support. Food supplies had been exhausted and the expectations of plundering Allied depots disappointed. Divisional commanders spoke of the `mental and physical depression’ of their men. Luckily, tens of thousands of Italian soldiers had again surrendered, with the result that the Allies were unable to mount a lethal counterattack. Karl dispatched two divisions as well as 46 batteries of heavy artillery to the Western Front to assuage the Germans; two other divisions would follow in September. Vienna ran out of flour on 17 June.

Arz von Straußenburg sent the Military Chancery his confidential assessment of the battle on 14 July. He began with a patronizing defence of the operation, claiming that it had spared his troops an `equally bloody, sacrificial defensive battle’. By tying down Allied forces on the Piave, he suggested, Vienna had in fact defended the Rhine! As to specific reasons for the defeat, Arz stated that gas shells had proved ineffective because the Italians had been outfitted with new British gas masks and because it had rained on 15 June. Deserters, including Czech officers from the 56th Infantry Regiment, had betrayed the time of the attack. The Chief of the General Staff failed to mention that rigidly timed rolling barrages did not work either while fighting in the mountainous terrain of the Tyrol or while fording a major river in Venetia.

Finally, Arz argued that Austro-Hungarian soldiers simply were not as good as German. Officers lacked the `originality’ of their northern colleagues. Nor were they steeped in the `Prusso-German military tradition’. With regard to the rank and file, each German soldier benefited from `cultural development, moral power, and sense of duty’. The Germans, in short, were `an organized people’; `all for one and one for all’. By contrast, the very diversity of the Multinational Empire militated against the development of such military and cultural cohesion. Line officers joked that Kaiser Karl had issued his ban on duelling to prevent them from killing General Staff officers!

The Chief of the General Staff’s strange lamentations were given more substance after the war by the Austrian official history. It censured Conrad generally for once more having undertaken an assault without proper regard for terrain, and specifically for having launched a frontal attack against eight enemy divisions well-entrenched in a deep forest. `There is hardly an example in military history . . . where an army has conducted an attack against a forest in closed formations according to plan.’69 Equally, the official history condemned Boroeviæ’s decision to press across the Piave without sufficient numerical superiority or proper equipment. It failed to point out that the Allies, in addition to the extensive use of machine guns, flamethrowers and trench mortars, had established an `elastic defence’ wherein the front lines were only sparsely manned and thus beyond the reach of Habsburg gunners.

A `broken man’, Conrad was dismissed on 15 July 1918 – and raised into the peerage with the title of Count. The Magyar Archduke Joseph succeeded as commander in the Tyrol. Arz von Straußenburg submitted his resignation, but the Kaiser refused to admit poor judgement by sacking `his Arz’ as Conrad’s successor. Boroeviæ took the brunt of charges of military incompetence and even treason. Incredibly, on 21 July Arz’s staff penned a new list of war aims that called for the annexation of Serbia and Montenegro.

Parliaments in both Budapest and Vienna railed against the military fiasco. Hungarian deputies again demanded a separate Magyar army, while their counterparts in Austria openly accused Empress Zita of treason. It was decided in the best tradition of bureaucratic obfuscation to establish a committee to investigate the origins of the defeat on the Piave. The report, finally submitted in December 1921 by two members of Conrad’s former staff, Edmund Glaise von Horstenau and Emil Ratzenhofer, caused a storm of protest as it totally exonerated the AOK!

The Battle of the Piave, while not a decisive battle in terms of territorial gains or losses, nevertheless destroyed what remained of the k. u. k. Army. Within 3 months, the number of Habsburg troops in Italy melted from 406,000 to 238,900; that of combatants from 252,950 to 146,650. Conservative estimates are that 200,000 soldiers deserted and that their numbers doubled by September. The Honvéd Ministry in Budapest calculated that 200,000 deserters were on the loose in Transleithania alone. Military officials in Galicia claimed to be looking for 30,000 deserters, while the fortress commander at Przemyol noted that 20,000 soldiers refused to report back from leave. The seven infantry divisions posted in the interior to combat unrest and rebellion never returned to the front. While the War Ministry continued to list a paper strength of 57 divisions in Italy, in reality these had the combat strength of only 37 full divisions. There can be no question that the Austro-Hungarian Army began to disintegrate immediately after Conrad’s last offensive.