Overview

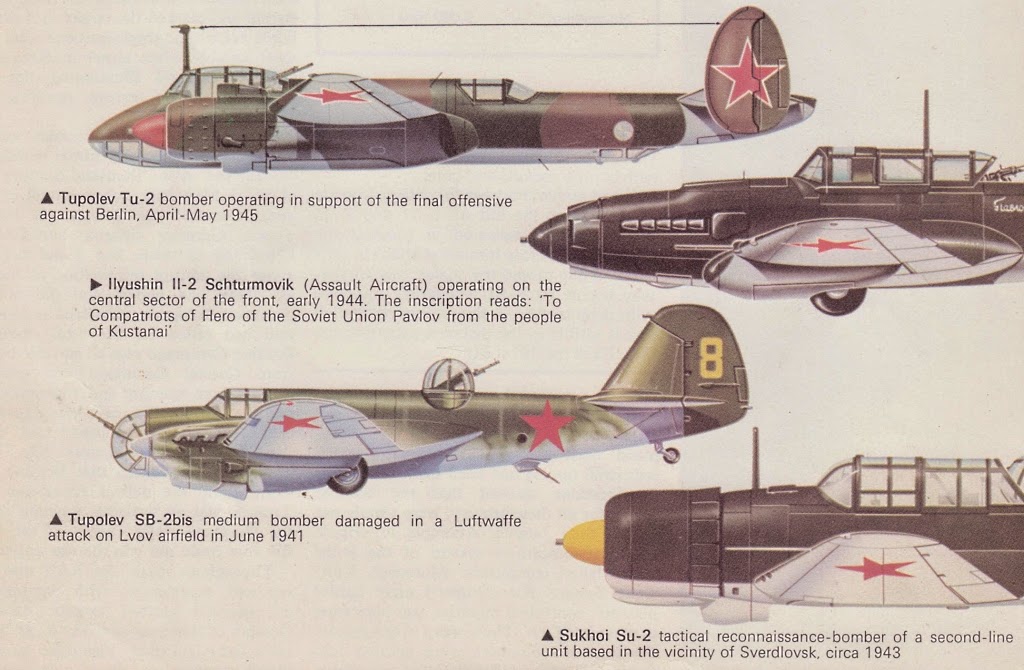

The first Five-Year Plans triggered a massive buildup of Soviet aviation, including many airplanes of indigenous design. Among them were maneuverable fighter biplanes, such as the Polikarpov I-15 and I-15 bis; the first cantilever monoplane with retractable landing gear to enter squadron service, the Polikarpov I-16; and a variety of bombers, including the Tupolev TB-7, SB-2/SB-3, and DB-3.Yet the Soviets failed to develop a reliable long-range bomber force. The established Soviet concept of air warfare envisioned the use of airpower predominantly in close support missions and under operational control of the ground forces command.

The Red Army Air Force under the command of Yakov Alksnis during 1931–1937 developed into a semi-independent military service with a combat potential, good training, and a logistics infrastructure spreading from European Russia into Central Asia and the Far East. Still, the Red Army Air Force exhibited marked deficiencies in several local conflicts (e.g., against the Chinese in 1929 and in the Spanish civil war, 1936–1939). In contrast, during the 1937–1939 air conflicts with Japan (China, Lake Khasan, Khalkin Gol) the Soviets effectively challenged the Japanese air domination and provided decisive close air support in the campaigns on Soviet and Mongolian borders. During the Winter War with Finland (1939–1940), however, the Red Air Force suffered heavy losses due to inflexibility of organization, its command- and-control structure, poor training of personnel, and deficiency of equipment.

The failures in Soviet airpower were reinforced by the terror of Stalinist purges. About 75 percent of the senior officers were imprisoned or executed, and some 40 percent of the officer corps was purged. The result was the critical decline of experience, initiative, and responsibility within the command of the air force and its combat personnel.

The main reason for the large aircraft losses in the initial period of war with Germany was not the lack of modern tactics, but the lack of experienced pilots and ground support crews, the destruction of many aircraft on the runways due to command failure to disperse them, and the rapid advance of the Wehrmacht ground troops, forcing the Soviet pilots on the defensive during Operation Barbarossa, while being confronted with more modern German aircraft. In the first few days of Operation Barbarossa the Luftwaffe destroyed some 2000 Soviet aircraft, most of them on the ground, at a loss of only 35 aircraft (of which 15 were non-combat-related). Many of these were obsolete types, such as the Polikarpov I-16, and they would be replaced by much more advanced aircraft as a result of both Lend-Lease and the miraculous transfer of the Soviet aviation industry eastward from European Russia to the Ural Mountains. The sporadic Soviet retaliatory strikes were poorly coordinated and led to devastating losses in aircraft and combat personnel.

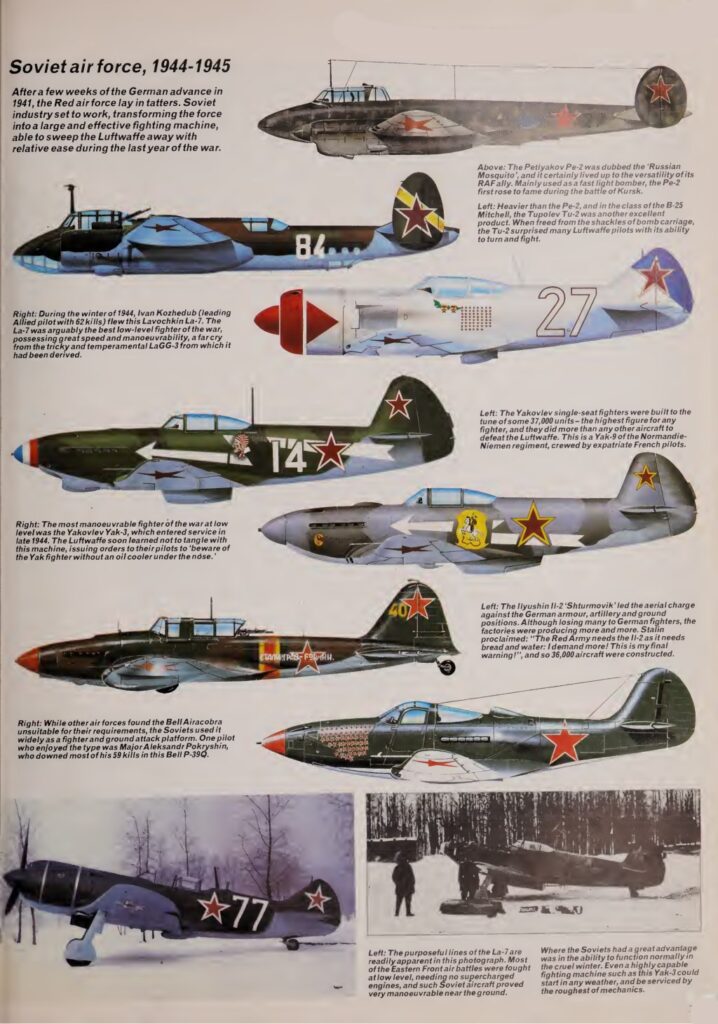

World War II caught Soviet aviation unawares—more than 1,200 aircraft were lost on the first day of the Nazis’ June 1941 invasion. For the next 6–8 months, aircraft and other factories were shifted eastward to the Urals and Siberia, a huge undertaking largely completed by early 1942. Relocation made transport of finished aircraft to the fronts more difficult, but by late 1942 and in 1943 Soviet aircraft began to appear in huge numbers. Germany’s output was exceeded in 1943. Fighters such as the Yak-3 and Yak-9 (more than 16,000 of the latter), Lavochkin La-5 (10,000), and La-7 (nearly 6,000) began to take a toll on German air strength. The Ilyushin Il-2 attack plane was the most-produced plane in the war (1,000 made every month after 1942 for total of over 36,000), and the later Il-10 reached production numbers of 5,000.

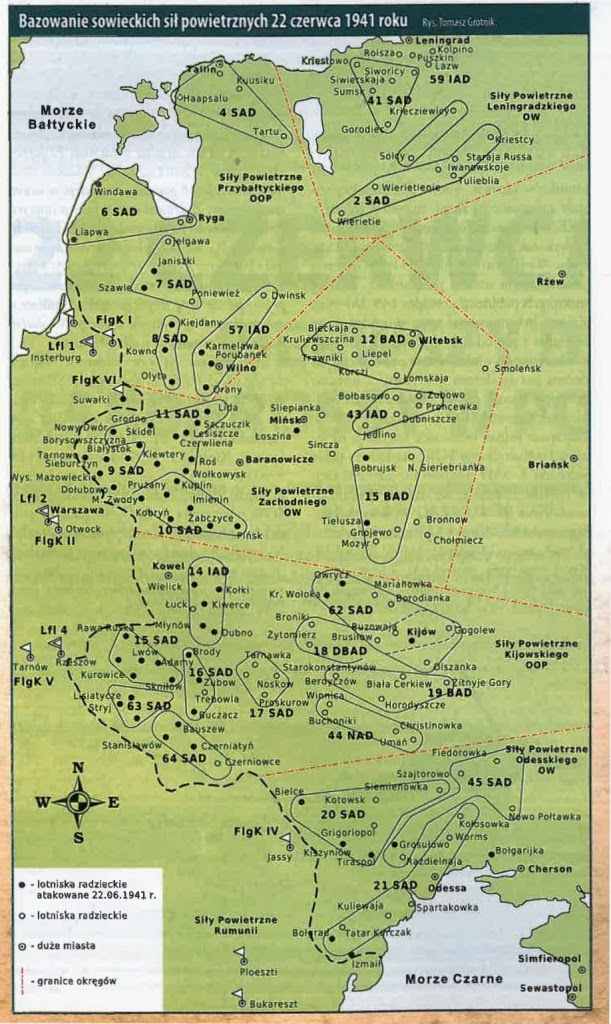

First Days off Barbarossa – Air War

First word of the attack arrived in Moscow in the form of a desperate signal from the commander of the Black Sea Fleet, who reported a devastating Luftwaffe raid was taking place against the naval base at Sevastopol. The report was disbelieved by Stalin until confirmed by direct telephone contact between Sevastopol and the Kremlin. Two hours later Ambassador Count von der Schulenburg delivered Germany’s declaration of war to Soviet Foreign Minister Vyacheslav Molotov.

Luftwaffe bombers located the Black Sea Fleet at anchor in Sevastopol by the oscillating light of the city’s powerful harbor lighthouse. Neither the harbor nor the city were blacked-out. Attack aircraft from other Fliegerkorps bombed Bialystok, Brest-Litovsk, Grodno, Kiev, Kovno, Rovno, Riga, and Tallinn without meeting any effective air or ground defense response. Two thousand outmoded VVS aircraft were destroyed in the first three days of battle, hundreds while parked in neat rows or great circles during the opening hours of the fight after dawn on June 22. Thousands more aircraft were shot from the sky by better trained and more experienced Luftwaffe pilots flying more modern planes. Some Soviet pilots crashed their slow and ill-armed monoplanes into faster and more powerful enemy aircraft, using suicide tactics to make up for the inadequacy of their planes. Such acts were not ordered, but on the first day they set a tone for the savagery to come in the east, for total war waged without pity on the ground or in the air, in the villages and countryside, and within hundreds of towns and cities. Thousands more VVS aircraft were abandoned on overrun airfields in ground panic over the first weeks. The most reliable calculations place the number of lost VVS planes at just under 4,000 within the first 15 days, compared to Luftwaffe losses of 550 aircraft. Initial Luftwaffe success was unparalleled in the history of air operations. It gave German pilots total domination above the battlefield for the first six months of the war. Air supremacy in turn permitted Luftwaffe commanders to switch to critical ground support and interdiction roles, ripping apart exposed Soviet columns, strafing and bombing pockets of surrounded Soviet divisions and whole armies. For most of the rest of the BARBAROSSA campaign the Luftwaffe thus concentrated on attacking tactical targets ahead of advancing ground forces of the Ostheer, and on interdicting Red Army fuel and ammunition supplies, troop trains, and columns on the march.

RED ARMY AIR FORCE (VVS)

“Voenno-Vozdushnye sily (VVS).” Unlike the Royal Air Force (RAF) or the Luftwaffe, but like the USAAF and JAAF, the VVS was not a separate air force organization. VVS bombers and support aircraft were integrated with various Fronts of the Red Army, while anti-aircraft guns and fighter-interceptors were organized separately under the PVO, or Air Defense Force. As a result of being controlled by ground force commanders, and given experience in the Spanish Civil War (1936–1939), during the prewar period the VVS built a nearly exclusively tactical air force of medium bombers, dive bombers, and heavy attack fighters. It eschewed acquisition of more than a handful of long-range strategic bombers. Joseph Stalin took a direct interest in the VVS. His limited prewar thinking about strategic bombing was influenced by the deep battle attack doctrine developed by the Red Army. In 1939 VVS “mixed air divisions” were set up that deployed bombers and fighters to each Front (army group). As a result, when war came VVS aircraft were widely dispersed among ground formations themselves deployed too far forward, and were not capable of a coordinated overall response to being suddenly attacked. The problem of commanded structure and overly wide dispersal was compounded by weakness in aircraft design. That would not change until 1942, with reforms forced upon the VVS by extraordinary pressures of catastrophic losses of aircraft and near-defeat of the whole Red Army in 1941.

The VVS underwent a violent purge that began in 1937, continuing to mid- 1941, the very eve of the German invasion. In addition to top officers, many talented aircraft designers were arrested, executed, or driven to suicide. Aircraft types were miserable in design compared to German or British models, but had been produced in great volume by the pathologies of a Soviet economic model that valued sheer numbers over quality. The inadequacies of the prewar VVS were revealed in extraordinary peacetime losses to accident: upwards of 800 aircraft per year, or more than the entire prewar production runs of some RAF models. A paucity of repair facilities, technical support, fuel supply systems, and ground-to-air or air-to-air radio communications completed the prewar picture. On June 21, 1941, the eve of the German–Soviet war, the VVS numbered 618,000 personnel, but not enough experienced or qualified officers. It deployed over 20,000 military aircraft of all types. In the first three days alone the VVS frontier Military Districts lost about 2,000 aircraft. Several top commanders were immediately arrested and shot, scapegoats for Stalin’s diplomatic and military catastrophe. During the first weeks of fighting the VVS lost thousands more outclassed planes, many destroyed on the ground or abandoned in all-out retreats. By the end of July it was a shattered remnant of its prewar self. Over the first six months of fighting its losses were even more immense.

Luftwaffe reconnaissance units worked frantically to plot troop concentration, supply dumps, and airfields, and mark them for destruction. The Luftwaffe’s task was to neutralize the Soviet Air Force. This was not achieved in the first days of operations, despite the Soviets having concentrated aircraft in huge groups on the permanent airfields rather than dispersing them on field landing strips, making them ideal targets. The Luftwaffe claimed to have destroyed 1,489 aircraft on the first day of operations. Hermann Göring — Chief of the Luftwaffe — distrusted the reports and ordered the figure checked. Picking through the wreckages of Soviet airfields, the Luftwaffe’s figures proved conservative, as over 2,000 destroyed Soviet aircraft were found. The Luftwaffe lost 35 aircraft on the first day of combat. The Germans claimed to have destroyed only 3,100 Soviet aircraft in the first three days. In fact Soviet losses were far higher: some 3,922 Soviet machines had been lost (according to Russian Historian Viktor Kulikov). The Luftwaffe had achieved air superiority over all three sectors of the front, and would maintain it until the close of the year. The Luftwaffe could now devote large numbers of its Geschwader to support the ground forces.

In all this it is useful to recall that three-quarters of all Wehrmacht soldiers who were killed in World War II lost their lives on the Eastern Front. Compared to that, the Western one was almost a picnic. Until the autumn of 1942 the German Army and the Luftwaffe units supporting it, though weakened to the point where they were no longer able to attack all along it as they had done during the previous year, still enjoyed superiority over the Soviets. The outcome was a series of spectacular victories that brought it to Stalingrad and to the gates of the Caucasus. While the quality of Soviet aircraft was improving, German pilots and organization, including above all the critically important field of communications, remained superior. Concentrating its forces, the Luftwaffe was still able to obtain clear air superiority at the time and at the place it wanted. The problem was that, given the relatively low number of machines and the huge spaces to be overrun, there were never enough forces to do a really thorough job. This was reflected in the tremendous effort of the Luftwaffe transport command; during this period it flew 21,500 sorties, covered over ten million miles, and delivered 42,000–43,000 tons of supplies.

Determined to dislodge the last remaining Soviet forces still clinging to the right bank of the Volga at Stalingrad, in October the Luftwaffe concentrated 80 percent of all its combat power against that city. During that month the bombers and dive-bombers of Luftflotte 4 flew approximately 20,000 bomber and dive-bomber sorties to assist General Friedrich Paulus’s Sixth Army. Targets consisted of remaining pockets of resistance as well as Soviet traffic across the river. However, the Germans did not have a free hand. As enemy resistance stiffened, the number of serviceable machines dropped by almost half. By the time the Soviet counteroffensive got under way on November 20, the Red Air Force, constantly growing in numbers and operating from bases east of the Volga, was in control of the sky. Particularly important was the German pilots’ inability, made worse by the closeness of the fighting on the ground, to identify their targets at night. For just that reason, it was at night that the Soviets sent most of their reinforcements into the beleaguered city.

The Soviet counteroffensive quickly led to the encirclement of the German Sixth Army. Some months earlier, in February–May 1942, about 90,000 German troops had been cut off by the Red Army, forming two pockets south of Leningrad. During that period the Luftwaffe was able to keep the encircled forces alive by flying in supplies and replacement troops and taking out the wounded. In the end the encircled formations were able to break the siege, although doing so cost them much of their heavy equipment. Now Goering told Hitler that the Luftwaffe might repeat the performance. Yet conditions were entirely different. Whereas the battle for Demyansk took place toward the beginning of spring so that the weather could be expected to improve, that for Stalingrad got under way just when winter was setting in. Whereas the troops at Demyansk needed a minimum of 265 tons a day to survive, the 220,000 at Stalingrad needed at least twice as much. Flying in and out of the city, the distances the aircraft had to cover were also much longer.

Mobilizing every aircraft and every crew, braving nights that were becoming increasingly longer, atrocious weather conditions, and growing Soviet resistance in the air and from the ground, the Luftwaffe, still flying mostly obsolescent Ju-52s, did what it could. However, during the entire period when the air-bridge was in operation only once did it succeed in delivering as much as 280 tons, whereas the daily average stood at a mere 90 tons. Toward the end, as more and more airfields were lost to the advancing Soviet columns, the Germans were reduced to dropping supplies by parachute, with the result that many were lost or fell into enemy hands. None of this could save the doomed Sixth Army; by the time it surrendered, the Luftwaffe’s transport command, having lost almost 500 aircraft and many experienced crews, had received a blow from which it would never recover.

The last occasion when the Luftwaffe on the Eastern Front was able to intervene effectively in the ground battle was at Kursk in July 1943, when it saved the German Ninth Army from encirclement and possibly annihilation. From this point on, in the air as on the ground, the boot was clearly on the other foot. Already during 1942 the quality of Soviet airpower had begun to improve; aircraft received wireless—from early 1943 on, every new machine was equipped with a set—and modern navigation aids. Soviet ground radar had now developed to the point where it was able to provide 15 minutes’ advance warning against approaching German aircraft, greatly facilitating interception and enabling commanders to do away with the wasteful practice of mounting air patrols around the clock. Stalin’s Falcons finally got around to adopting the staggered four-finger formation, the outcome being a notable improvement in the scores of air-to-air combat.

By this time the Soviet aviation industry, much of which had been hastily evacuated to the territory east of the Ural Mountains in 1941, was back in full operation. Partly for that reason, partly because of the Luftwaffe’s decision to focus on the defense of the Reich, the Red Air Force also enjoyed a very great quantitative advantage. One result was that the number of air-to-air encounters actually declined, as was later to happen in the west too; there simply were no German planes or pilots left to carry on the fight.

This in turn meant that the Soviets, assured of air superiority at most times and places, were able to focus on air-to-ground attack. Like their enemies and their allies, they developed a system of forward air observers. They were fully motorized and used radio telephony to work with ground commanders down to the regimental level. Tactics, too, improved. At Stalingrad, deficient arrangements for air-to-ground cooperation made Soviet air support almost totally ineffective. Now, with the battle moving to and fro (but mostly to) over the enormous, almost featureless expanses, things became a lot easier. Smaller, more flexible formations numbering three or four aircraft were adopted. Pilots learned to launch their attacks from the west, especially during the late afternoon when the sun would blind the German defenders. While tactical bombers—the only ones the Soviets had—fighter-bombers, and ground attack aircraft flew both battlefield support and interdiction sorties, the Soviets continued to differ from the western Allies in that they always preferred the former to any other kind. By one calculation they devoted as many as 40–50 percent of all sorties to that task. This was almost as many as those devoted to air superiority (35–45 percent), interdiction (4–12 percent), and reconnaissance (2–13 percent) combined.

The number of Soviet combat aircraft grew from 1,327 at Stalingrad to no fewer than 7,496 during the climactic Battle of Berlin. The daily number of sorties went up from 500 at Stalingrad to 2,600 at Kursk to 4,157 at Berlin. Whereas at Stalingrad each aircraft flew 0.37 sorties per day on the average, two years later the figure stood at 0.55. Losses were heavy in proportion. Out of 33,700 ground-attack aircraft built, no fewer than 23,600, or 70 percent, were destroyed—12,400 by enemy action and 11,200 by accidents of every kind. All this fits in well with a report that, soon after the war, Stalin was shocked to learn that fully 47 percent of all losses had been due to accidents. As so often was the case, the discovery immediately led to an investigation into the nefarious activities of assorted so-called wreckers and enemies, though its results are not recorded. Yet in one respect the Soviets were fortunate. Given that almost all their aircraft were single- or twin-seaters, personnel losses were proportionally much smaller than those suffered by the western Allies in particular; in the long run, smaller losses translated into greater accumulated experience.

Air Battles in Kuban Air

The German-held Kuban bridgehead, situated along the Taman peninsula, was an area of extreme importance to both sides. The Germans saw the region as essential to protecting the eastern approaches to the Crimea , whereas the Soviets viewed the bridgehead as a launch-point for another possible German offensive into the northern Caucasus . Unlike Stalingrad, Kursk or even Operation Bagration, the campaign is almost unknown in the West, probably due to the fact that there were no real breakthroughs on the ground, no encirclements, no capitulation of German armies. At best, it was a set of limited ground offensives during the boggy months of spring.

However, the air battles over the Kuban sector were pivotal to the growth of the VVS as the offensive long-arm of the Red Army, sending a clear message to the Luftwaffe: the VVS was about to return what it had received. In fact, Soviet historians hold this two-month air campaign in early 1943 to be as important to the war effort as the Americans do the battle of Midway. It was a battle fought with such intensity that General K. V. Vershinin, the main Soviet air commander of the sector, claimed on some days he could see an aircraft fall every ten minutes, and it was not unusual for as many as 100 air battles to take place in a day.

The German Fourth Luftflotte (Air Fleet), which included Fourth the elite Udet, Molders and Green Hearts JGs (Jagdgeschwader, equivalents of Groups), was responsible for this area, while its Soviet counterparts were primarily the and Fifth Air Armies, along with three air corps from STAVKA reserves. Both air forces were roughly equal in size at about 1000 combat aircraft each. The Luftwaffe fighter units were mainly equipped with Bf 109 G 2/-4’s and Fw 190 A’s, while the VVS possessed a mixture of the latest Yakovlev and Lavochkin fighters, along with large numbers of 11-2 Sturmoviks and Pe-2 bombers. In addition, there was a steady flow of lend-lease aircraft: P-39’s, A-20’s, P-40’s and even Spitfire V’s. Though Soviet pilots found the Spitfire a disappointment (it looked too much like a Bf 109 and was very vulnerable to groundfire), they flew the P-39 with great elan during the battle. In fact, two pilots of 16 GvIAP (Gvardeiskii Istrebitelnii Aviatsionnii Polk, or Guards Fighter Air Regiment), A. I. Pokryshkin and his squadron mate G. A.Rechkalov, were very successful flying the P-39-the former claiming 20 kills during the battle.

Phase 1: Myskhako

The battle began April 17, 1943 when the German Seventeenth Army launched Operation Neptune, focused upon the Soviet beachhead at Myskhako. German Ju 87’s tried to dislodge the Soviets and initially the divebombers were unopposed, but within three days VVS fighters arrived to stop the attacks. Though Soviet fighter pilots claimed 182 Luftwaffe aircraft destroyed in the following week, the losses were considerable for both sides. In the end, Soviet resistance was so stiff the Wehrmacht was forced to abandon its attack.

Phase 2: Krymskaya

The second phase of the battle began when the Soviet 56th Army launched a major ground offensive on April 29. The objective was to establish a breakthrough corridor to Anapa, a coastal town deep in the German rear on the Black Sea. The offensive began around the village of Krymskaya , which had great strategic value due to its position north of Novorossisk and close to a key railroad junction. By this time the VVS had considerable numerical superiority, so much so that the Luftwaffe lost an average of 17 fighters a day up to May 10th; in total some 368 German aircraft were claimed by the VVS. However, once again the Soviet air force was also paying a heavy price in aircraft losses, and by May 9 / 10 the Luftwaffe had actually regained air superiority over Krymskaya. After the Soviet 56th Army made only limited gains, a two-week lull ensued.

Phase 3: Blue Line

On May 26th, the Soviet offensive was renewed along the fortified German “Blue Line” with a powerful armored infantry thrust. Within hours of the Soviet assault, the Germans launched a determined counterattack that soon stalled the Soviet drive. As a result, more than 100 Soviet tanks were lost on the first day. In the air, the response from both sides was immediate and uncompromising. The VVS had launched a preparatory raid of 338 aircraft. The Germans responded with up to 1,500 sorties on the same day. German sources state that the VVS lost 350 combat aircraft on May 26th alone, but overall air losses to the Luftwaffe were so severe that they discontinued active air engagements in the area on June 7th. During this third phase of the campaign many reputations were made: the Glinka brothers, Dmitrii and Boris, scored 21 and 10 victories respectively in the Kuban , A. L. Prukozchikov-20, V. I. Fadeyev-15, N. E. Lavitsky-15, D. I. Koval-13, V. I. Fedorenko-13 and P. M. Berestnev-12.

On July 5, 1943 German operation Zitadelle began, only to be called off by Hitler twelve days later after German forces suffered substantial losses in their advance. The Soviets quickly seized the initiative, beginning their counteroffensive just as the German offensive was stalling. This turn of events did not bode well for the Germans deployed in the Kuban Bridgehead, especially after the Soviets occupied all land routes to the Crimea by October 13, 1943. That same month, the Kuban Bridgehead was evacuated by German forces.

Major air campaign that marked the shift from German to Soviet air superiority on the Eastern Front during World War II. During April and May 1943, as the Germans struggled for their last North Caucasus foothold, Luftflotte 4 (Fourth Air Force) clashed with the Soviet 4 and 5 Air Armies, the Black Sea Fleet Aviation, and Long Range Aviation. Air activity was intense, often seeing as many as 100 air combats a day.

German forces began with about 900 aircraft, including the latest models of the Bf 109G and the Hs 129, and featured some of their top units, including Jagdgeschwader 52 with Erich Hartmann. The Soviets began with about 600 aircraft, swelling to 1,150 in May. The Soviets also committed their newest aircraft, including the first use in the south of the Douglas A-20, as well as the Bell P-39D, flown by Aleksandr Pokryshkin’s air division.

The Soviets showed a new aggressiveness in flying offensive fighter sweeps, and they introduced new tactics, including German-style four-plane formations and Pokryshkin’s Kuban Ladder, a stacked formation. Also playing a distinguished role was the Soviet women’s night-bomber regiment. The campaign ended suddenly on 7 June, at which point the Soviets had claimed 1,100 German aircraft destroyed; the Germans claimed 2,280 victories, but the tide of the air war had turned against them.

As so often was the case, just how much Soviet airpower affected ground operations is impossible to say. To be sure, we are told that “air cover and support from the tank armies that carried the burden of the major Soviet offensives after 1944 were critical to the overall success” and that “the [Frontal Air Force] was the most mobile, flexible, and powerful means for supporting tank armies during deep operations.” However, the question remains as to how critical “critical” really was. Whereas German records and memoirs pertaining to the West often stress the role of Allied airpower, when it comes to the Red Air Force they are of little help. To the very end, the German generals tended to look down on their Soviet enemies, attributing the latter’s victories, and their own defeats, to hammer-like blows delivered by overwhelming numbers rather than to any tactical and operational finesse. Always it was the supply system that broke down, or some neighboring unit that gave way, rather than they themselves who were defeated. For most of these generals, admitting that Soviet successes in the war in general, and in the air war in particular, might be due to qualitative superiority was little but heresy; during the Cold War, such an admission would cast doubt on Germany’s usefulness to its newly found NATO allies.

Soviet Women Combat Pilots

In the months leading up to Operation Barbarossa (Hitler’s code name for the attack on the Soviet Union) there had been over 500 violations of Soviet airspace by German photo reconnaissance aircraft. On the 21st June 1941 Hitler attacked – his plan to crush the Soviet Union in 10 weeks. Initially the attack exceeded the wildest dreams of the German generals. The fall of Smolensk to the Germans on July 16, 1941 placed Moscow in danger. Hitler then discontinued the drive to Moscow, ordering the Germans to stand in place – it seemed to postpone the final blow but consequently Moscow received a reprieve during those crucial weeks. When the belated and ill-timed German assault on Moscow (code – named Operation Typhoon) began at 05:30 hours on September 30, 1941 the Russian weather turned foul.

The rainy season (rasputitsa), made any activity difficult, with the roads turning muddy so only large vehicles could move and air operations from grass fields becoming nearly impossible.

For Operation Typhoon to achieve success, a quick victory over the Russians west of Moscow became urgent. The rasputitsa ended each fall with the arrival of winter frosts and this created a great challenge, especially trying to keep men and machines in fighting condition in the advancing cold. The winter turned out to be Russia’s most trusted ally.

Despite its reduced numbers, the Soviet Air Force (VVS) played an active role in the period prior to the final German offensive. During Operation Typhoon the VVS, sensing that the final assault had commenced, then began to reassert itself, boldly attacking advancing German troops and armour by day and night.

Night bombing, mostly by PO-2 Biplanes in the tactical zones, became common place during Operation Typhoon. Bombing missions were sometimes carried out in extreme weather but ideal conditions were the long moonlit or starry nights.

The Polikarpov PO-2 was a 1927 design, powered by a single 115 hp engine giving a top speed of 81 mph and a range of 280 miles but it made a significant impact on the German troops by maintaining a sustained air presence over the battle zone, continuously harassing the Germans. The PO-2 was highly maneuverable and the slow speeds made night interception by the fast German fighters a difficult undertaking. The VVS pilots would often stop their engines and glide to the target, dropping their bombs by hand.

The night attackers, nicked named “sewing machines” or “duty sergeants” forced the enemy on all fronts to take precautions, lose sleep, and on occasion suffer the loss of a storage or fuel depot.

Soviet women pilots, the so-called “Night Witches”, acquired considerable fame in this dangerous pursuit.

In October 1941 Soviet women pilots were organised into combat regiments by Marina Raskova, a famous Russian aviatrix. In 1938 she had received acclaim for flying an ANT-37 across the vast terrain of the Soviet Union (eleven time zones!) to achieve a women’s record of 3,672 miles in 26 hours, 29 minutes. Raskova, who was later killed in action and buried in the Kremlin wall, called for volunteers for women’s air regiments over the Moscow radio. The women were to be front line pilots, like men, and there were to be three air regiments, each with three squadrons, mechanics and armament fitters.

The training base was in a small town called Engels on the River Volga, North of Stalingrad. Here they were issued with men’s uniforms – which were far too big – many stuffing their boots with newspaper and tying belts around their waists. With Maj Marina Raskova as Commander and Maj Yevdokia Bershanskaya as 2nd in command women went through an intense training schedule – 2 years work into 6 months. Marina Raskova and Yevdokia Bershanskaya had to assess the volunteers, and most wanted to fly fighters.

In all, VVS women pilots flew more than 24,000 sorties during the war – sixty eight receiving the Gold Star, Hero of the Soviet Union award.

The girls never wore parachutes and, after discussing it amongst themselves, had agreed if captured they may have to shoot themselves. This is exactly what Alina Smirnova did. When she crash landed she lost her sense of direction and when some people ran towards her, she thought they were Germans and shot herself.

586th Fighter Regiment

The women had trained in PO-2 aircraft and found the conversion to the powerful, single seater Yak-1 very difficult. The instructors could only drum into them the characteristics and limits of power and control before their first flight. The 586th Women’s Fighter Regiment was first to go to the front. Commanded by Tamara Kazarinova, they flew the Yak-7B and Yak-1, totalling 4419 operational sorties, and credited with 38 victories.

The principal role of this regiment was to drive off enemy bomber formations before they reached their targets. Encounters with Messerschmitt 109s escorting the bombers were common.

Squadron Commander Olga Yamshchikova flew 93 sorties, scored three confirmed victories, and after the war became the first Soviet woman to fly jet aircraft when she became a test pilot.

Lilya Litvyak and Ekaterina Budanova both flew with the 586th. Maj Tamara Kazarinova noted they had a flair for individual combat so they were both transferred to join the men of the 73rd Fighter Regiment who were involved with some furious battles over Stalingrad. The City of Stalingrad had been continuously bombed by enemy aircraft, the city burning for many kilometres, and smoke hung over the city like a blanket. Over a million people died in the Stalingrad battle, for Germany it was the first great disaster of the war. This was a different kind of combat for the girls, joining the Free Hunters and seeking out fighters.

When the women arrived, male pilots found it difficult to accept them. Many refused to have them fly as their wingman, some later relenting after the women proved they were more than capable. Many commanders wanted to protect them even though they continuously proved their abilities. The women flew their missions together.

Both Lilya Litvyak and Ekaterina Budanova became fighter aces. Ekaterina Budanova was credited with eleven victories, and Lilya Litvyak scored twelve official victories and three shared in her year with the 73rd Fighter Air Regiment before her Yak was lost on August 1, 1943.

The women’s 586th Fighter Regiment was heavily drawn into the most crucial battle of the war, to be fought at Kursk.

It was 2.20 am on Monday, July 5, 1943 when the Germans commenced an attack that was to develop into the greatest tank battle of the war. Fortunately “Lucy” – a complex spy ring, had forewarned the Russians of the battle plans. Together the two fronts had more than 1.3 million men, 20,000 field guns and 3500 tanks; 4000 aircraft of both sides were operating over an area only 12 miles by 30 miles. It was not unusual for 300 fighters to be involved in combat.

German airmen were always surprised to encounter VVS women pilots in active combat roles. One Luftwaffe pilot, Maj. D B Meyer, remembered being attacked near Orel by a group of Yak fighters. During the ensuing air duel the jettisoned canopy of Meyer’s fighter struck the propeller of one of the pursuing Yaks, forcing it to crash. Upon landing Meyer found his dead adversary to be a woman – without rank insignia or parachute.

588th Night Bomber Regiment

The 588th Night Bomber Regiment (Night Witches) later received the honour of the 46th Guards Bomber Aviation Regiment – the first women’s regiment to receive this honour, placing them among the elite of the fighting units. The 46th Guards Bomber Aviation Regiment first arrived over the Southern Front in May 1942, commanded by Yevdokia Bershanskaya. Fighting from the Kuban to Berlin, this all women’s regiment flew 24,000 combat missions and dropped 23,000 tons of bombs from the then battle-weary PO-2 biplanes.

Twenty-three of its fliers and navigators became heroes of the Soviet Union for their dangerous work, including flights on the night of July 31st 1943, when four of their two seaters were shot down over the Blue Line (the secured German Sector of the Kuban bridgehead) by a German Junkers Ju 88 bomber.

This regiment remained entirely female throughout the war.

587th Dive Bomber Regiment

The 587th Dive Bomber Regiment later received the honour of the 125th Guards Bomber Aviation Regiment. The regiment did not go into battle until January 1943, delayed because of an abrupt change of aircraft. The crews had trained on the two-seater SU-2 but at the last minute were allocated the three seater PE-2 dive bomber instead, the regiment consequently having to wait for additional training and personnel.

The PE-2 had a crew of three – pilot, navigator, and a radio operator/gunner. The aircraft had two fixed machine guns firing forward and a swivelling machine gun in an acrylic bubble behind the navigator. The pilot had an armoured seat in the cockpit with the navigator behind, also in an armoured seat. The radio operator sat at the rear in the fuselage. When the aircraft was fully loaded with fuel and bombs the navigator used to help pull back on the stick to get the nose off the ground.

Later during the war the regiment began to receive male replacements. There were not enough women trained to fill the positions.

Russian Air Power 1924 to 1941 Part I

Russian Air Power 1924 to 1941 Part II

Developing Tactics for the Il-2

A. I. Pokryshkin

“Achtung! Achtung! Pokryshkin is in the air!” these words made German pilots feel panic. Nobody wanted to meet him in one-to-one fighting.

A. I. Pokryshkin became famous during the battles in Kuban, in spring 1943. Air battles in Kuban air were the most severe in the history of the World War II. Battles were going the whole days and as sky was black from such number of planes. German historians admitted that Kuban battles marked the beginning of crash of fascists aviation.

A. I. Pokryshkin worked out new tactics of air battle, they were sent to all other air armies and adopted by pilots. There, in Kuban, his famous formula was born: ” Height, speed, maneuver, fire!” A. I. Pokryshkin also introduced a new system of teaching of young pilots that was more successful than the older one.

According to the last archive investigations, A. I. Pokryshkin destroyed 116 German planes. He was the first person to get the status of the Hero of the Soviet Union 3 times! A. I. Pokryshkin is considered as one of the best pilots of the World War II. After the war he became the marshall of aviation. A. I. Pokryshkin is the author of 4 books about aviation and the war.

Yakov Alksnis

After graduation from the Red Army Military Academy (1921–1924) Alksnis was appointed the head of logistics service of Red Air Forces; in 1926 deputy commander of Red Air Forces. In 1929 he received wings of a fighter pilot at the Kacha pilot’s school in Crimea and was later known to fly nearly every day. Defector Alexander Barmine described Alksnis as “a strict disciplinarian with high standards of efficiency. He would himself personally inspect flying officers… not that he was fussy or took the slightest interest in smartness for its own sake, but, as he explained to me, flying demands constant attention to detail… Headstrong he may have been, but he was a man of method and brought a wholly new spirit into Soviet aviation. It is chiefly owing to him that the Air Force is the powerful weapon it is today.” According to Barmine, Alksnis was instrumental in making parachute jumping a sport for the masses. He was influenced by one of his subordinates who has seen parachutists entertaining public in the United States, at the time when Soviet pilots regarded parachutes “almost a clinical instrument”.

In the same year he was involved in establishing one of the first sharashkas – an aircraft design bureau staffed by prisoners of Butyrki prison, including Nikolai Polikarpov and Dmitry Grigorovich. In 1930–1931 the sharashka, now based on Khodynka Field, produced the prototype for the successful Polikarpov I-5. In June 1931 Alksnis was promoted to the Commander of Red Air Forces, while Polikarpov and some of his staff were released on amnesty terms. In 1935, Red Air Forces under Alksnis possessed world’s largest bomber force; aircraft production reached 8,000 in 1936.

In June 1937 Alknis sat on the board of the show trial against members of Trotskyist Anti-Soviet Military Organization; he himself was arrested on 23 November 1937, expelled from the Communist Party, charged with setting up a “Latvian fascist organization” and shot 28 July 1938.

During the destalinization of the late 1950s Alksnis was posthumously rehabilitated; the Air Forces college in Riga was named in his honour. Viktor Alksnis (born 1950), grandson of Yakov Alksnis, is a right-wing Russian politician remembered for his pro-Union activities of the late 1980s and early 1990s.