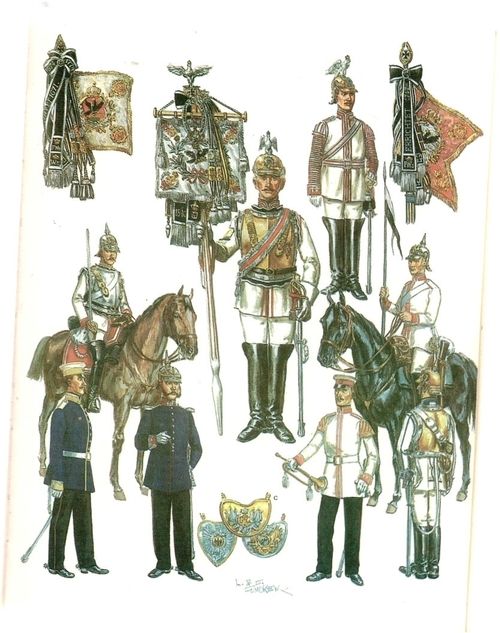

Late 19th century Prussian Cuirassiers

The countryside around Konitz simmered in the warm September sun. The fields were not planted. There were no rivers and few trees. An occasional, gentle rise in the landscape was all that interrupted the drab flatness of the area. Located in the Baltic province of West Prussia, far from the burgeoning cities and metropolises of industrializing Imperial Germany, Konitz offered the added attraction of its isolation. This was probably what appealed most to Prince Friedrich Karl, nephew of the old emperor and the empire’s first inspector general of the cavalry. Indeed, the prince, turning more irascible and peculiar with every year since the great Wars of Unification, did not like outsiders to observe his annual cavalry exercises.

Friedrich Karl stood atop a tall observation platform. Next to him were veteran cavalry generals just as enthusiastic as he was about the great impact that mounted warriors would have in a future war. For a week, two cavalry divisions had maneuvered against each other, roaming widely through the countryside around Konitz. Now, to hold down costs, just one division remained. The generals’ binoculars focused on a spot about a mile away, where 3000 Teutonic horsemen were drawn up for battle.

That day’s exercise was a tactical drill. The attackers would hit the enemy’s flank, engaging his squadrons and beating them back. Assigned the task of breaking through were the Third East Prussian and the Fifth West Prussian Cuirassiers, their breastplates gleaming gloriously in the late summer sunlight. A second strike wave of lesser strength, about 100 meters behind the first, consisted mainly of lighter cavalry, including the famous “Blücher” Hussars of the Fifth Pomeranian Regiment. Their job was to protect the flank and rear of the first wave or to hurl themselves forward if a rout of the enemy was imminent—or if the Cuirassiers failed. Two regiments of Uhlan lancers stood in reserve about 400 meters behind the Cuirassiers. Barely visible from the platform was a regiment not assigned to this attack.

When the order was given, the Cuirassiers moved forward at a trot. After a few hundred meters the pace quickened to a slow gallop as the squadrons performed a diagonal echelon maneuver and prepared for the final charge into the enemy line. At this point Friedrich Karl swung his binoculars back to the left to observe the dispositions of the Hussars, the Uhlans, and the flanking regiment. Indeed, one of the main goals of the exercise was to coordinate the movements of the three waves with nearby units to maximize the advantages of attacking in great strength. The frown on the prince’s face was indication enough that these formations were not showing proper initiative in supporting the attack. Further irritation followed when he noticed that the charging heavy cavalry had pulled up short, thinking, apparently, that it was just a drill.

Friedrich Karl’s final report attempted to derive lessons that would be useful in the next maneuvers—and in the next war. “Three-wave tactics” would be effective in battle,” he wrote, but the battlefield itself was no place to improvise them. These tactics had to be practiced in peacetime exercises that simulated actual battle conditions—including charges of cheering Cuirassiers ridden through to the end—until the commands and their execution became routine. Unfortunately, the German cavalry had little wartime experience with massed attacks. The result was that supporting and neighboring units were unclear and confused about their roles. The main goal of a successful charge was for the charging division to attract all nearby cavalry into the fray “like iron drawn to a magnet.” Only a “well-schooled” cavalry division with good leaders would be “the cutting edge that decides a battle.”

The great cavalry exercises at Konitz in September 1881 were the high-water mark of a remarkable revival in the fortunes of the German cavalry. The golden era of mounted warfare that Friedrich Karl and his professional entourage revered had lapsed into legend more than a century earlier. At Rossbach (1757), Leuthen (1757), and Zorndorf (1758), Prussian cavalry generals had led successive strike waves of Cuirassiers and Hussars that justified the confidence and faith of their great warrior monarch, Frederick II. This tradition crashed to the ground, however, during the Napoleonic wars, nor was the succeeding generation kind to Prussia’s horsemen. Industrialism brought not only rifled steel cannons with greater range and accuracy but also mass-produced infantry rifles; the Prussian “needle gun”; and the French chassepot, which fired much more rapidly than the old muskets. Consequently, the cavalry was assigned no major role in Prussia’s wars against Denmark (1864) and Austria (1866). The three Prussian armies that descended on Bohemia in the latter campaign deployed their cavalry in the rear. These units saw only limited action in the last hours of the great battle at Königgrätz.

The turnaround began during the Franco-Prussian War of 1870. Indeed, a new cavalry legend was born as Germany’s three armies marched west into Lorraine to engage Marshal François Bazaine’s Army of the Rhine near Metz. Bazaine seized the initiative on 16 August against the German Second Army of Friedrich Karl, attacking him at Mars-la-Tour before the German First and Third Armies could offer support. Outnumbered and pounded by superior French artillery, the Second Army was in a precarious position. Orders for an attack were therefore issued to General Bredow’s cavalry brigade, consisting of one regiment of Cuirassiers and one regiment of Uhlans. Charging in one unsupported wave, the roughly 800 riders overran enemy infantry and artillery positions, penetrating some 3,000 meters before they were forced to retreat. The “Death Ride of Mars-la-Tour” had cost Bredow 379 men and 400 horses, but he had purchased valuable time for the Second Army. There were altogether eight cavalry charges during the battle, pitting cavalry against infantry, artillery, and opposing cavalry. Deciding the day, in fact, was a great clash of about 6,000 German and French riders. Although Mars-la-Tour was a bloody draw, Bazaine fell back to defensive positions near Metz, where the Germans attacked with greater success 2 days later.