The influence of aviation on intelligence activities was not limited to photographing the territory of other states. The use of aircraft greatly simplified the problem of delivery of agents and saboteurs. It was a real revolution in the work of the secret services! Previously agents were able to enter the territory of other countries only by land or by sea. To carry out this mission, it was necessary to cross the border or the front line unnoticed, then make a long and risky journey through a hostile country. Communication with agents operating in another state was also difficult, not to mention how to get them out. With the advent of aircraft with long range and large capacity, this problem was solved. Now agents could be secretly delivered to any reachable point, either dropping by parachute or being landed directly on the ground. Subsequently the plane could deliver equipment and money to them, and bring them back after the mission. In the Third Reich, the organizer of this activity was Theodor Rowehl and his subordinate units.

Back in the late 1930s, Abwehr had established preliminary contacts with the Ireland Republican Army (IRA), an illegal nationalist organization fighting for the annexation of Northern Ireland to the Irish Free State and complete independence from the UK. These took place in Maidstone Prison where a few leaders of the IRA were serving their sentences alongside the German Lieutenant Gortz, who had been sentenced to four years’ imprisonment for espionage.

In February 1939, the Abwehr-I agent Oskar Pfaus met with the ‘Army Executive Board’ of the IRA. With his help, in the autumn, after the outbreak of war, radio communication was established between German intelligence and the IRA. In February 1940, the submarine U-37 (Korvettenkapitän Werner Hartmann) delivered a German agent, Ernst Weber-Drohl, to Donegal Bay on the west coast of Ireland to assess the possibilities of cooperation with the IRA. But during the landing, he dropped his radio into the water and was unable to communicate with his superiors. By April, Weber-Drohl had been arrested by MI5 and quickly agreed to work for the British, becoming a double agent.

British counterintelligence acted very energetically and effectively. By the beginning of 1940, almost all Abwehr agents in the UK, who were controlled by Hauptmann Herbert Wichmann, were working for the British. Thirty-nine spies were arrested and turned. One of the most valuable agents – the Welshman Alfred Owens, who had the Abwehr code name ‘Johnny – had actually been working for MI5 since the late 1930s. The British gave him the code name ‘Snow’ and, using his radio transmitter, supplied the Germans with misinformation.

In order to land their agents as close as possible to their destination, Abwehr-I used the aircraft of the 2nd Staffel of Aufkl.Gr.Ob.d.L. Its commander was Oberleutnant Karl-Edmund Gartenfeld, who was considered an expert in these delicate matters. He was born on 27 July 1899 in Aachen and began his military career during the Great War. After flight training, he, like Rowehl, served in naval aviation. After the surrender of Germany, he was demobilized and subsequently worked for Deutsche Lufthansa. In 1936, Karl-Edmund Gartenfeld joined the Luftwaffe and was assigned to Fliegerstaffel z.b.V., and then in 1939 was appointed commander of the newly-formed 2.(F)/Aufkl.Gr.Ob.d.L.

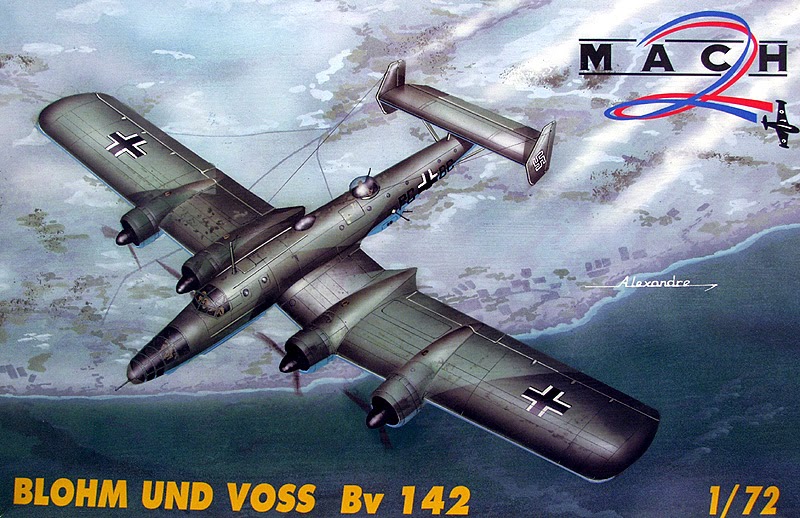

Secret missions to drop agents into enemy or neutral countries required flying in unfavourable conditions, i.e. at night and with heavy cloud cover. He 111, BV 142 and Fw 200 aircraft were commonly used for these missions. The skill of the pilots and navigators of the Gartenfeld squadron allowed airdrops of agents within no more than 8km of the target area. But on some occasions they made significant navigational errors.

On the night of 6 May 1940 Oberleutnant Gartenfeld was assigned to deliver the next Abwehr agent to Ireland, in the Dublin area. The agent was again Lieutenant Gortz, who had served his sentence in an English prison, returned to Germany and ‘again took up his old ways’. Now he was to create an illegal organization for sabotage and sabotage in Ireland, controlled by Abwehr and independent from the unreliable IRA. The Germans didn’t trust the rebels very much because they had a lot of internal conflicts.

The German navigator made a mistake, and the plane crossed the east coast of Ireland about 80km north of Dublin. Gartenfeld mistook the lights of the port of Dundalk to his left for the lights of the Irish capital and he continued his flight into the depths of ‘neutral Ireland’. As a result, when Gortz parachuted to the ground, in the morning he realized with horror that he was in Armagh in Northern Ireland, that is, on British soil. With great difficulty, the agent was able to get to Dublin, where he met with the chief of staff of IRA Stephen Hayes. But his mission in Ireland ended in failure. Having taken all the money Gortz had with him, the IRA actually gave him up to the authorities. In November 1940, the agent was arrested and imprisoned, where he was to be repatriated to Germany. A few months later, fearing that the Irish authorities wanted to hand him over to the British, Gortz committed suicide.

In early 1940, Abwehr-II, in charge of the organization of subversion and sabotage, created the first special unit for sabotage and reconnaissance operations behind enemy lines. In order to maintain secrecy, it received the name Lehr und Bau Bataillon z.b.V. 800 (800th Special Purpose Training and Construction Battalion) and was based in the city of Breslau (now Wroclaw, Poland). The battalion’s airborne training was held at the airfield in Oranienburg, where 2.(F)/Ob.d.L. under Karl-Edmund Gartenfeld was based. Its personnel initially acted as instructors and later delivered their former cadets to their destinations.

On 28 May 1940 everything seemed normal. A group of Abwehr agents had gone up in a single-engined Junkers W.34, piloted by Gartenfeld himself, for practice parachute jumps. Everything was going fine until it was the turn of Leutnant Loebner. Due to the excitement he pulled the ripcord prematurely, and his parachute caught on the tail of the aircraft. This was a critical situation. Gartenfeld could not land on the runway with Loebner caught on the tail, so he decided to set the plane down in water. He so carefully planted his Ju W.34 on the surface of the Teltow canal, passing through the southern part of Berlin that Loebner escaped with only a slight concussion. For his actions, on 25 July Oberleutnant Karl-Edmund Gartenfeld was awarded the Rettungsmedallie (Lifesaving Medal).

The Abwehr continued it attempts to play the ‘Irish card’. If nothing else, Ireland seemed to the Germans a convenient ‘back door’ for dropping off their agents into the UK. In early May, German intelligence organized a visit from the neutral United States to Germany of two famous Irish dissidents – the former chief of staff of the IRA Sean Russell and Frank Ryan. The Germans hoped that these two could make the IRA play a more active role in sabotage and subversion in Britain. The operation to deliver them to Ireland was codenamed ‘Taube’ (‘Dove’). In early August, Russell and Ryan boarded the submarine U-65 (Korvettenkapitän Hans-Geritt von Stockhausen), which was to land them on their home coast. However, the operation failed before it began. During the voyage Russell suddenly died of a perforated gastric ulcer, and the submarine returned when it was only half-way to Ireland. In June an aircraft of 2.(F)/Ob.d.L. delivered a new agent, Wilhelm Preetz, to Ireland, but he was soon arrested.

The intelligence services of the Third Reich sometimes formulated quite adventurous plans involving Ireland. One such example was Operation ‘Kathleen’. The Germans knew that the Irish government was afraid that Britain might invade their territory to seize it and use the most important ports and airfields for their own purposes. Therefore, the idea arose to offer the Irish ‘help’ to protect themselves from possible aggression by ‘the peaceful’ landing of German troops in Ireland. It was planned that German ships with soldiers on board would leave the French Atlantic ports and then come to Ireland from the west disguised as ships under the Irish flags coming from the United States. In Oranienburg the 1st Special Unit SS was formed for this mission, whose members, in order to disguise its true purpose, were allegedly preparing for a raid on the Suez Canal.

The plan for Operation ‘Kathleen’ was presented to Reich Foreign Minister von Ribbentrop, who transmitted a proposal to the Irish Prime Minister, Eamonn De Valera. The government of Ireland initially expressed interest in the ‘noble care’ of the Germans, but after a long discussion on 17 December 1940 gave a negative answer. The reason for the refusal lay in the fact that, no less than the British themselves, the Irish government was afraid of strengthening the radical IRA!

After a successful campaign in Western Europe in May–June 1940 and the surrender of France, Hitler hoped that England would make a peace offer itself. He tried to make it clear that he was ready to negotiate and even compromise. But Prime Minister Winston Churchill was not going to stop the war and make peace with the Nazis. In response to Churchill’s ‘stubbornness’, on 16 July the ‘offended’ Führer signed Operational Directive No. 16, which stated the need to prepare a landing operation for the occupation of England. At the same time, the deadline for its start was set for mid-September.’

OKW had developed a plan for this operation under the code name ‘Seelowe’ (‘Sealion’). Twenty-five Wehrmacht divisions were to cross the English Channel, land between Dover and Portsmouth and then move on to attack London. But German strategists were faced with a shortage of tactical intelligence about the forces and means at the disposal of the British. Therefore, the Abwehr was given the task to fill this deficit. This could only be done by sending a large number of new agents to England. Operation ‘Lena’, as the training and insertion of these agents was code-named, received the highest priority. In practice, this meant that preparation of agents was carried out hurriedly at the most basic level. Many of them, recruited from countries occupied by the Third Reich, spoke little English. But the Abwehr did not attach much importance to this, because they believed that the ‘lifetime’ of such agents before the invasion would be short.

These experts were right, but they had no idea quite how short their agents’ ‘lifetimes’ would actually be. Failures plagued Operation ‘Lena’ from the very beginning. On 3 September, several agents were dropped by parachute from a 2./Aufkl.Gr.Ob.d.L. aircraft, and almost simultaneously another group of four Dutch agents landed on the Kent coast from a fishing boat. Less than 36 hours after disembarkation, they were all arrested by the British. In December, three of the Dutchmen who refused to cooperate with MI5 were executed as saboteurs.

Late in the evening of 5 September another He 111 from Gartenfeld’s staffel took off from the airfield at Chartres in France. On board was agent No. 3719 – Gösta Caroli – who had a Swedish passport, a British identity card and a German radio set. He landed by parachute west of Northampton. Three days later Caroli was arrested and agreed to work for the British. He received the MI5 alias ‘Summer’ and until the end of the year regularly passed ‘information’ to the Abwehr, which he received from the British, but Caroli tried to escape from the safe house where MI5 kept him, but was caught and remained in prison until the end of the war.

On the night of 19 September, agent No. 3725 – Wulf Schmidt – parachuted from an He 111 piloted by Hauptmann Gartenfeld. He landed near the village of Willingham, 13km north-west of Cambridge. He was arrested within the first day, and he also quickly agreed to cooperate with the British. Schmidt received the alias ‘Tate’. Thanks to the ‘help’ of MI5 he was considered by the Abwehr to be one of their most valuable agents in the UK! ‘Tate’s’ merits were appreciated by both sides: the Germans awarded him the Iron Cross, and the British gave him British citizenship after the war!

At the end of September, Abwehr began to employ other Luftwaffe units for the delivery of agents. On the night of 30 September, an He 115 seaplane from Ku.Fl.Gr.906 took off from Sula in Norway. It brought three agents to the coast of Northern Scotland, two men and one woman. In a rubber dinghy they reached the shore near the town of Banff. The landing went unnoticed, but despite this, the whole group was soon caught. This happened because the woman – Vera de Witte – was actually already a double agent working for MI5. Two other agents – Theodor Druge and the Swiss Werner Waelti – were executed in 1941 after refusing to cooperate with British Intelligence. On 25 October, another group of three Abwehr agents were landed on the coast of the Moray Firth, near the city of Nairn, again from an He 115. It included the German Otto Joost and two Norwegians – Gunnar Edvardssen and Legwald Lund. Their mission was also ‘impossible’.

The stories of Abwehr agents who were delivered to the UK by sea and air differed only in dates and minor details. According to British sources, all of them were identified and arrested. Some spies were sentenced to death, others to prison, but most were employed as double agents. However, there is evidence that several agents had managed to evade the watchful eye of MI5.

So, at the end of October near the town of Amersham (20km north-west of London), the Dutch agent Jan Willen ter Baak was dropped from a 2.(F)/Ob.d.L. aircraft. His parachute was found in a deserted area by the British on 3 November, but they couldn’t find the agent. Baak regularly made radio contact with the Abwehr-I sub-group ‘Hamburg’, in charge of intelligence in England. On 1 April 1941 the agent was found in one of the bomb shelters in Cambridge with a bullet in the head. According to the official version, he committed suicide. But now we can say that it was not so. The Dutchman was a double agent, but he did not work for MI5, but for Soviet intelligence. Probably one of the parties just punished Jan Willen ter Baak for the betrayal. Whether he was killed by Russians or Germans is still unknown!

On the night of 15 November another Do 217 from the Rowehl Group was over the south of England. On board, in addition to the crew – Oberleutnant Siegfried Knemeyer and Leutnant Rhunke – were two Abwehr agents and Hauptmann Gartenfeld. He had to control the delivery. Nothing is known about the tasks of the agents, but two circumstances pointed to their particular importance. First, the plane had an ‘extra’ passenger – the commander of 2.(F)/Aufkl.Gr.Ob.d.L., which was very unusual. Second, the night chosen for the drop was the night when the Luftwaffe bombers made the infamous massive raid on Coventry, and the British air defences couldn’t track a single plane. Knemeyer later recalled: ‘Everything over southern England was illuminated by searchlights looking for our bombers. Near Bristol we encountered heavy anti-aircraft fire and for a long time were in searchlights.’ However, the Do 217 avoided being hit and delivered the first agent – a Norwegian – to Birmingham. The second – a student from South Africa – was dropped in the Dartmoor area. To date, there is no evidence that the British were able to detect them.

Operation ‘Seelowe’, scheduled for mid-September, never began. On 13 September, Hitler, taking into account the results of the air campaign against England conducted by the Luftwaffe, ordered it to be postponed until the end of the month. Then, in October, it became clear that Göring would not be able to fulfil his boast to destroy the RAF and ensure Luftwaffe’s complete air supremacy over the English Channel and southern England. The date of the beginning of the operation was postponed several times until on 9 January 1941 Hitler finally gave the order to cancel all preparations.

From mid-October, the preparations for ‘Seelowe’ was in fact only a screen and a cover for another military operation long conceived by Hitler. This was the plan ‘Fritz’, which soon received a new name – Operation ‘Barbarossa’. Under this name it went down in history. It was a plan for an attack on Russia …

Gradually, the Abwehr curtailed its operation for the large-scale delivery of agents to the UK. This was facilitated not only by the success of MI5, but, by the end of 1940, by increased RAF night fighter activity. Flights at low and medium altitudes over the English Channel and the North Sea had become extremely risky. As a result, in the first half of 1941 only two agents were dropped by parachute in England, Josef Jakobs on 31 January and Karl Richard Richter on 14 May. They were arrested, refused to cooperate with MI5 and were executed the same year.

In fact, for the special staffel of the Luftwaffe the operations to deliver agents to Ireland and England were really just exercises. The Germans did not know that the war would last for many years, and that they would have to deliver thousands of agents behind enemy lines!