The Main Offensive

He returned to Lugdunum in the spring of 10 BCE. The Tres Galliae continued to function as expected and there were no reports of unrest. His legates, meantime, had wasted no time in Germania. The Lippe River was now being lined with forts and logistics depots to relay supplies along the river delivered from Vetera. Work on Oberaden continued. A new supply depot to support the fortress was established a few kilometers downstream at Beckinghausen. Discovered in 1911 on a steep slope falling towards the river, it was subsequently excavated and an oval shaped encampment was uncovered measuring 185 meters (606.9 feet) by 88 metres (288.7 feet), encompassing an area of approximately 1.56 hectares, although the landing place for loading and unloading rivercraft has yet to be found. The main campaign this year would not, however, be driven along the Lippe River. Drusus now shifted the tactical thrust into Germania from a base further up the Rhine. A few weeks later he arrived with his entourage in Mogontiacum eager to launch an offensive to the Elbe via the River Main (Moenus or Menus). There were two legions at the camp, XIV Gemina and XVI Gallica. They may have been joined by vexillations of other legions from Fectio, Oppidum Ubiorum, Novaesium and Vetera. Detachments of these already made up at least two garrisons inside Germania. They would have been under orders to engage in simultaneous operations to drive deeper thrusts of their own into the territories building on the previous two campaign seasons; and to consolidate their gains with the construction of new forts, watch towers and roads. A skeleton crew would also have to be left at Mogontiacum (and the other Rhine fortresses) to guard it and manage the supply chain of provisions going to the front. Thus in practice the force for the new invasion along the Main River might have numbered as few as 10,000 men plus cohorts of auxiliaries.

A new fort may have been established at Frankfurt-am-Main-Höchst at the confluence of the Nidda and Main Rivers. As in the previous campaigns, Drusus used rivers to ferry much of the supplies his invading force needed by boat. The Main River is 524 kilometres (325.6 miles) long and a major tributary of the Rhine, with its source near Kulmbach, which is in turn fed by two minor tributaries the Red Main and White Main. The invasion plan was conceived with the usual Roman attention to detail, and logistics in particular. A supply depot was established at Rödgen near Bad Nauheim on the east bank of the Wetter River close by its source, about 60 kilometres (37.3 miles) east of the Rhine. It was polygonal in shape with a double ditch, 3 metres (9.8 feet) deep and wood-and-earth rampart structure 3 metres (9.8 feet) high and 3 metres (9.8 feet) wide at the base, enclosing an area of 3.3 hectares. Archaeologists found that the gateway, flanked by substantial towers, was wide enough for two wagons to pass through. These would have delivered corn and fresh produce brought up from Mogontiacum for storage in the warehouses and granaries inside the compound. There was also a well-equipped workshop. In the centre of the fortified camp was a principia, praetorium and barrack blocks sufficient for about 1,000 men but the size of the storage capacity meant it would feed many more mouths than its garrison. The nearby fort at Friedburg may have been connected with it.

The invasion route took them headlong into conflict with the Chatti who were a strong opponent. Unlike the previous campaign season, they had finally formed an alliance with the Sugambri and combined forces, having abandoned their own country, which the Romans had apparently given them. The Chatti were tough fighters and the ensuing conflict with the Romans was bloody and brutal. On the far northeastern edge of Chatti territory the Roman army established a major summer camp at Hedemünden near modern Göttingen, some 240 kilometres (149.1 miles) northest of Mogontiacum. Military surveyors laid out a narrow oval fortress taking full advantage of the Burgberg, a hill overlooking a bend on the Werra River, which is a tributary of the Weser. The defensive enclosure measured 320 metres (1,049.9 feet) long by 150 metres (492.1 feet) wide encompassing an area of 3.215 hectares. The 760 metre (2,493.4 feet) long circuit of wall measuring 5–6 metres (16.4–19.7 feet) at the base with a ditch outside was pierced by one gateway on each of the west and south sides, two on the east side with a curved but ungated northern end on the crest of the hill. There was an adjoining annex, also surrounded by a protective wall and ditch, which swept down to the riverside and may have been used for animals and supplies. The site, which has been partly excavated, has already produced over 1,500 iron objects carried by Roman troops, including exceptionally well preserved dolabra and pugiones, flat bladed spear points, the bent metal shank of a pilum, pyramid-shaped catapult bolts, nails, chain, hooks and even tent pegs with rings for tying the leather straps to. More personal items were also found such as iron hobnails – 600 in all – from caligae and a bronze phallic good luck charm. That the Romans were in the area on active campaign and taking prisoners is attested by an exquisitely nasty set of iron fetters. Shaped like the letter P the loop fitted around the neck and the hands were locked in two cuffs attached to the shaft. The short length of the shaft meant the captive wearer had to keep his arms up high across his chest – where they could be clearly seen by the guards – to avoid discomfort to the neck.

Anticipating his people might suffer a similar fate, one tribal leader took proactive steps to avoid conflict with the invaders. That year an enterprising noble from the Marcomanni nation named Marboduus or Marabodus, who was educated at Rome and once enjoyed Augustus’ patronage, returned to his people – or perhaps was taken there under Roman escort – and became their leader. He took back with him ideas about how the Marcomanni might introduce Roman-style law, government and military science. He had come to know the Romans well and understood what motivated them. Rather than challenge Rome or be subjugated by her, Marboduus decided upon a radical strategy. In a remarkable move, he convinced his tribe to relocate far from Roman temptation. Joining his people on the migration to a new homeland in Bohemia (Bohaemium) were the Lugii, Zumi, Butones (or Gutones), Mugilones and Sibini nations, a combined force of some 70,000 men on foot and 4,000 horse.

For those standing in Drusus’ path, the choice was ally with him or be prepared to fight. While the invading Roman army continued to attack and defeat any opposition as it progressed through the country, Drusus engaged in dazzling displays of single combat.

Spoils of War

Waging war was a central defining characteristic of Roman culture. There was prestige and profit to be had in a successful campaign and to advance in politics meant showing courage and ability on the battlefield. Fifty-three years earlier Cicero had exhorted

preëminence in military skill excels all other virtues. It is this which has procured its name for the glory of the Roman people; it is this which has procured eternal glory for this city; it is this which has compelled the whole world to submit to our dominion; all domestic affairs, all these illustrious pursuits of ours, and our forensic renown, and our industry, are safe under the protection of military valour. The highest dignity is in those men who excel in military glory.

One way a commander could prove his worth was to engage his opponent in face-to-face combat, defeat him and strip his body bare of its arms, armour and personal effects. These rich spoils were called the spolia opima. They were then hung decoratively from an oak tree trunk as a trophy (tropaea) and the victor brought the display back to Rome and presented it as victor to the shrine of Iupiter Feretrius on the Capitoline Hill. Their exalted place in the Roman psyche was due to their extreme rarity. Legend had it that the first spoils were taken by Romulus from Acro, king of the Caeninenses in 752 BCE following the incident in which the Sabine women were raped. The second spolia were those of Lars Tolumnius, king of the Veientes, taken by A. Cornelius Crossus. The decaying linen cuirass and accompanying inscription were still in existence in Augustus’ time and they actually came to light during the renovation of the temple of Iupiter Feretrius at the request of the princeps.

The last recorded Roman commander to be recognised for wrenching the spoils from his fallen adversary was M. Claudius Marcellus (c.268–208 BCE). He was a distant relative of Drusus and as a child he would have heard the thrilling story, which is preserved by Plutarch, of how he captured them in 222 BCE. Day and night, the story went, Marcellus pursued the Gaesatae, a Gallic tribe, which had invaded the Lombardy region of northern Italy to assist their allies, the Insubres. He finally intercepted 10,000 of them at Clastidium. Unfortunately, Marcellus had with him just 600 lightly armed troops, as well as a contingent of heavy infantry and some cavalry. Viridomarus, king of the Insubres, thinking that his side had the advantage of greater numbers and proven skill in horsemanship, set out to squash the Roman invader without delay. The Gauls were now heading en masse at speed towards Marcellus’ forces. Fearing he would be overwhelmed, the consul deployed his men into longer, thinner lines with the cavalry placed at the wings. His own horse, however, was terrified by the ululations of the advancing Gauls and turned tail, carrying Marcellus back in the direction of the Roman lines. This did not look at all good in front of his own men, so thinking quickly on his feet, he made as if he was praying to the gods and promised to Iupiter Feretrius the choicest of the Gallic king’s weapons and armour. Meanwhile, Viridomarus standing in his war chariot and wearing his striped trousers had spotted Marcellus by the splendour of his kit and charged out to slay him. Seeing the gleaming silver and gold of the Gaul’s armour and the elaborate coloured fabrics of his tunic and cloak, and recalling his vow to the Roman god, Marcellus now charged atViridomarus.The adversaries raced closer and closer together. Marcellus saw an opportunity but he had to act quickly. With all his might, he hurled his spear. The slender iron tipped weapon sliced through the sky and found its prey. The blade pierced the Gallic king’s cuirass and the force of the impact thrust him off his chariot and crashing to the ground. Marcellus charged up on his steed and dismounted. With two or three stabs, Marcellus dispatched the man.145 He hacked off the dead man’s head, removed the torc from his severed neck in the manner of the Celts, and stripped the dead man of his splendid gear. Lifting them skywards Marcellus proclaimed,

“O Iupiter Feretrius, who observest the deeds of great warriors and generals in battle, I now call thee to witness, that I am the third Roman consul and general who have, with my own hands slain a general and a king! To thee I consecrate the most excellent spoils. Do thou grant us equal success in the prosecution of this war”.

The Roman cavalry then charged the Gallic horse and infantry and won a great victory, made all the more so on account of the small number of Marcellus’ force and the greater odds it faced. The Gaesatae withdrew and surrendered Mediolanum (Milan) and other cities under their control and sued for terms. The senate awarded Marcellus a triumph in which the spoils were prominently displayed to cheers from the spectators. The sight of Marcellus carrying the trophy adorned with Viridomarus’ spectacular armour to the temple of Iupiter Feretrius was “the most agreeable and most uncommon spectacle”, writes Plutarch. Some 175 years later a descendant of Marcellus who was a tresvir monetalis used his position to commemorate the event on a special denarius.

There was another ancestor on Drusus’ mother’s side whose story probably inspired the young commander to uncommon acts of bravery on the battlefield. That was the story of how his family acquired its cognomen Drusus. One of his ancestors had dueled a Gallic chieftain named Drausus and by killing him “procured for himself and his posterity” the name.

These tales of heroism and glorious deeds evidently left a deep impression on the young Claudian. The German War provided Drusus with numerous opportunites to win his own rich spoils. Suetonius remarks that he was eager for glory and “frequently marked out the German chiefs in the midst of their army, and encountered them in single combat, at the utmost hazard of his life”. Drusus may have been successful in his quest, “for besides his victories”, writes the biographer of the Caesars, “he gained from the enemy the spolia opima”. If indeed Drusus was successful – when and against which opponent is not recorded in the surviving accounts – this was an extraordinary honour. The last person to claim the honour was M. Licinius Crassus (the grandson of the triumvir) who had defeated an opponent in Macedonia in 29 BCE. His achievement was downplayed, however. Politics got in the way of him collecting his trophy. The honour was deemed too distracting to Octavianus’ efforts to consolidate his political power. Crassus was denied his eternal glory and fobbed off with a triumph. By the time Drusus had taken the rich spoils from his Germanic enemy Augustus’ power base was more solid and he could afford to allow his young stepson the public recognition. Indeed, it would have been first rate propaganda for here was a member of his own household who had achieved what only three other illustrious men had in the entire course of Roman history.

Family Matters

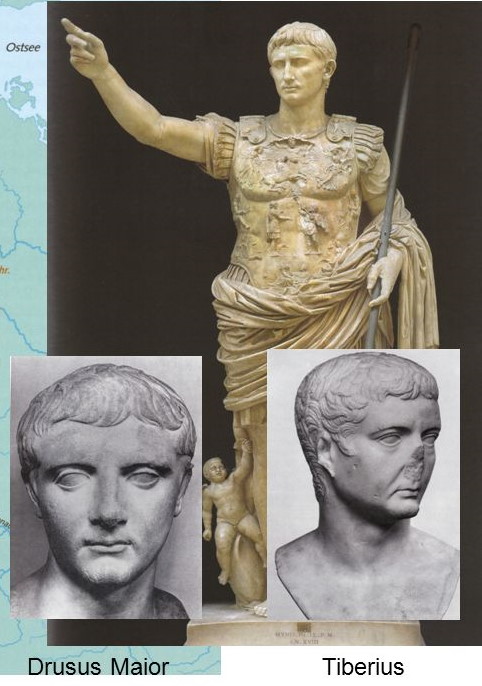

While Drusus was fighting in Germania, his brother was into the second year of a bitter campaign in Illyricum and Pannonia.157 It was not a war of conquest, for that had already been undertaken several years before, but the less glamorous burden of suppressing a rebellion. In 10 BCE Tiberius had yet to celebrate his first official triumph. Was Tiberius jealous of his younger brother’s high profile successes across the Rhine? Was Tiberius suspicious that his brother had become Augustus’ favourite? There is certainly a suggestion in the Latin literature of sibling rivalry and deeper resentments. Suetonius uses the word odium, ‘hatred’, to describe Tiberius’ feelings towards his younger brother at an undisclosed time in their relationship. As the only evidence for it he cites that Drusus had written a letter (epistula) to his elder brother in which he proposed they strongly urge Augustus to resign and for him to restore the institutions of the res publica. Tiberius “produced the letter”, presumably handing it over to Augustus himself. The consequences of this alleged action are not recorded, but Drusus’ preference for the old form of government was apparently well known, so it is hard to see how this could be damaging to him – unless it was this letter that revealed his true feelings and it was the first time Augustus learned of them. The letter does, however, strongly suggest that Drusus would have been opposed to a hereditary succession – including his own.

It was now summer and Drusus had to leave the campaign in the capable hands of his legates. There was a matter of provincial importance that required his return to Lugdunum. On 1 August the concilium Galliarum was to gather at the pagus Condate for the official opening of the sanctuary. The date chosen for the inauguration was significant on several counts. For the Gallic nations on this day they celebrated the start of the Lughnasa, the festival of Lug, the god of war and craft who had come to be associated with the Roman Mercurius. For the Romans, 1 August was the “natal day” of the temples of Victoria and Victoria Virgo on the Palatine Hill and on this day, Augustus had taken Alexandria from Kleopatra in 30 BCE and Drusus had taken the oppidum of the Genauni fifteen years later.

The sanctuary complex commissioned by Drusus was a spectacular expression in stone, marble and gilt bronze of the burgeoning ‘theology of victory’ that legitimized Augustus’ vision for an expansionistic Roman commonwealth and of the place of Tres Galliae in it. The creation of a cult centre shared between three provinces was unprecedented anywhere in the Empire but relates back to the reorganization of the Tres Galliae under Augustus between 16–13 BCE and the need to create a common bond between its diverse civitates. It was appropriately grand. Visitors to the complex crossed from Lugdunum via a bridge over the Saône River. They first saw the amphitheatre, which dominated their field of view. An elaborate wooden one- or two-storey superstructure supported rows of seats for some 1,800 spectators who sat around an oval-shaped sand-covered arena measuring 67.6 metres (221.8 feet) by 42 metres (137.8 feet).