Chatti Germanic Tribe | Northern Germanic Tribes: Cherusci, Jutes, Saxons.

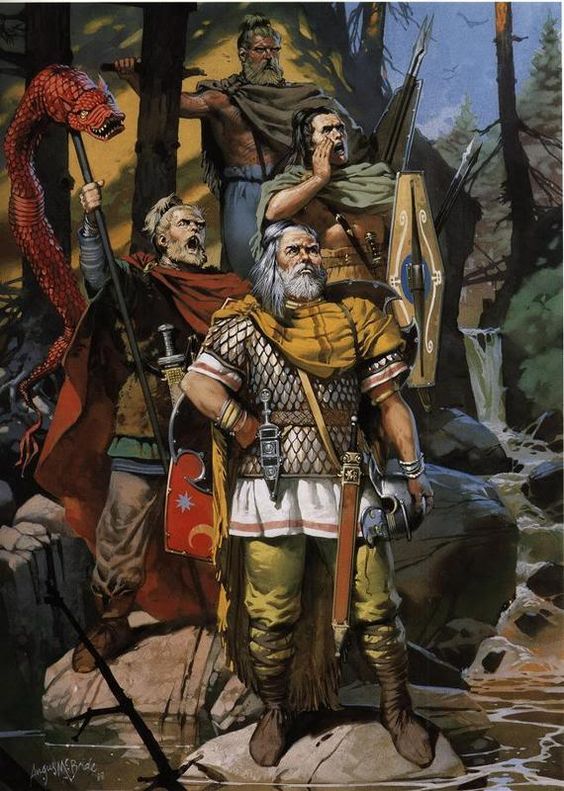

Early Germanic warriors either first century BC or AD. The Germans east of the Rhine had a fearsome reputation and constantly waged war on their Gallic neighbours. The Gauls who lived close to the German border were considered to be the most hardened of the Gallic peoples as a result.

Ambush at Arbalo

Drusus’ expeditionary army continued to progress through Cheruscan territory. The Cherusci, meanwhile, had been tracking the Romans from a distance. They had the tactical advantage, knowing where to hide and when to launch surprise attacks. Using stealth, concealment and deception, the Cherusci constantly assaulted Drusus’ troops with surprise hit-and-run attacks, but they proved ineffectual as Roman discipline held. However, at a place called Arbalo the Cherusci finally unleashed a major ambush that tested Roman resolve. Dio describes the place simply as “a narrow pass”, which is not much to go on in trying to identify the site today. Several attempts have been made and a consensus view has formed on the area around Hildesheim or Hameln.

Drusus’ army was at its most vulnerable on the march. It would have been in a defensive formation for marching in hostile country, but that still meant it was strung out over many kilometers with its impedimenta, the long baggage train, slowing down the pace. Once the bulk of Drusus’ men had entered the narrow pass, the Cherusci sprung their attack. They blocked both the Romans’ advance and their retreat. In this confined space Drusus and his army now found themselves trapped. It was the kind of battle Drusus did not want to fight. The Cherusci rained down their missiles – frameae, darts and slingshot – upon the cramped, snaking Roman lines. In marching order there was not much space between the men for them to deploy their weapons. Under the hail of missiles whistling through the air and unable to quickly deploy in their battle formations they were ‘sitting ducks’ at the mercy of their opponents. Each legionary carried not only his heavy arms and shield, which on the march was protected by a goat-skin cover, but he was weighed down by his personal gear and tools hanging from a pole over the left shoulder, which combined was not only heavy but swung awkwardly as he marched, especially over uneven ground. Tribunes and centurions screamed out orders to the rankers to drop their shoulder packs, to form defensive lines and hold their heavy covered shields up high. The baggage train was either drawn back into the line or abandoned, but inevitably the animals panicked and their handlers struggled to restrain them. Drusus’ men resisted fiercely as they took the shock of the Germanic charge, wielding their gladii as they tried to cut their way through the blockade at the front while fending off the onslaught from the sides. Under their helmets, sweat trickled down from their brows, stinging their eyes. Hands gripped tightly the inside of the bosses of heavy shields, which suddenly felt lighter as adrenaline surged through the legionaries’ veins. It was a terrible situation that Drusus and his men were now in. Germanic wooden clubs struck Roman iron armour. The cries of attackers met the groans of wounded men. The living tried to avoid treading on the bodies of the dead.

Despite their valiant efforts the legionaries and auxiliaries began to sag under the continuing assault in this unfavourable terrain, and to tire under the weight of their equipment and the physicality of their exertions. It may have been during this action that the two military tribunes, Chumstinctus and Avectius, both young Nervii from Gallia Belgica, distinguished themselves with acts of gallantry – though precisely what they did which merited mention by Livy has been lost.

Then, inexplicably the German attack appeared to waver and some of the warriors even seemed to withdraw. Up to that point the Cherusci had had the upper hand during the struggle. In Dio’s account they did not press home their advantage out of “a contempt for them, as if they were already captured and needed only the finishing stroke”. The Cheruscan leadership, perhaps among them Segimer himself, seemed to have decided that defeating an enemy in this manner was not honourable. The change of heart, however, also broke the resolve of the main body of Cheruscan warriors and those who continued the fight found themselves unsupported by their brothers now hesitating from a distance behind. It was an amazing stroke of good luck for the desperate Romans and exactly the chance Drusus needed. Urging his men on, Drusus broke through the Cheruscan blockade. Against the odds, the Romans escaped. The Cherusci had also lost their one opportunity to deliver a knockout blow – perhaps one that might have ended Roman ambitions for taking Germania. Cheruscan scorn or indecision perhaps more than superior Roman arms and tactics had saved the day for Drusus.

How could it have happened? It seems someone had not been paying adequate attention to the surroundings. Had the advance Roman scouts simply been duped or failed in their duty? Or had Drusus disregarded the intelligence in an example of overconfidence or overeagerness? The ancient sources do not say, and although Roman casualties are not known, yet clearly Drusus had come perilously close to losing his army altogether that day. Nevertheless Pliny the Elder characterised Arbalo as “a brilliant victory”. He ridiculed the men who had misinterpreted the swarm of bees. Arbalo was “a proof, indeed, that the conjectures of soothsayers are not by any means infallible, seeing that they are of opinion that this is always of evil augury”.

In the eyes of the common soldiery too 26-year old Drusus had brought them a great victory. He was a soldier’s soldier. He maintained the love and goodwill of his men who now showed it by spontaneously acclaiming him with their right arms raised and loudly shouting the salutation ‘imperator!’ – meaning simply ‘commander’. It was in the gift of the soldiers to acclaim their commander on the field of battle in this manner in a tradition extending over hundreds of years. The concept of imperator had originally been used in a religious context but became a military honour when Scipio Africanus was acclaimed by his soldiers for his victory in Hispania which he ascribed to a special relationship he had with the father of the gods, Iupiter. The use of the title was encouraged by Marius, Sulla, Caesar and Augustus. Believing Drusus the commander would lead his battered army back to the safety of the winter camps on the Rhine, his soldiers cheered heartily; but Drusus was not content to simply abandon his hard won gains. To retain his stake and probably to signal that he intended to return the next year, Drusus decided to post garrisons inside Germanic territory. One fortified stronghold was erected provocatively in Cheruscan territory “at the point where the Lupia and the Eliso unite”. The location of the site has been debated for over a 150 years. The Eliso may have been the Alme River, and where it intercepts the Lippe River today is modern day Paderborn, some 60 kilometres (37.2 miles) east of the Rhine. This tends to support a case for the fort being at Haltern laying 54 kilometres (33.5 miles) from the Rhine and located on the course of the Old Lippe River. The site has been extensively excavated and the first structure that can be identified was a marching camp roughly square in shape covering an area of 36 hectares, which is large enough for two legions. A V-shaped ditch and turf rampart surrounded the camp, but no permanent structures have been identified suggesting it was a temporary structure and probably unsuitable for occupation in winter. Close to the riverbank, a triangular enclosure was erected around a steep hill-top which commands a view of the valley. Called the Annaberg Fort it was likely a stores compound. It was built later than the marching camp and has been tentatively dated to Drusus’ campaign period.

The other prime contender for the site of Aliso is Bergkammen-Oberaden situated northeast of Dortmund, 70 kilometres (43.5 miles) east of Vetera. A Roman camp was identified here in 1905 and timber finds have been precisely dated using dendrochronology to the autumn of 11 BCE, which is therefore the earliest date work on the fortress began. Roughly heptagonal in shape (map 8), at 57 hectares (840 metres by 680 metres; 2,755.9 feet by 2,230.9 feet) the fortress was large enough to accommodate up to three legions and auxiliaries. Its planners chose a hill-top for the base and constructed a formidable 2.7 kilometre (1.7 mile) long wooden curtain wall around it with a 3 metre (9.8 feet) wide rampart behind and towers spaced out at 25 metre (82.0 feet) intervals. In front of it, a 5 metre (16.4 feet) wide, 3 metre (9.8 feet) deep ditch was dug but on the northern side, the ditch was wider and narrower at 6.5 metres (21.3 feet) by 2.5 metres (8.2 feet), and staked with 300 sticks sharpened at both ends, one of which has survived and is on display at the Westfälisches Römermuseum in Haltern am See. An estimated 25,000 trees were felled to provide the timber for this massive encampment. The finds from the site suggest the fortress was built to be occupied all year round and its inhabitants seemingly suffered no discomforts during their stay. The principia, which was the office of the legate and his administrative staff, was finished with painted plaster, pieces of which were uncovered during excavations with the imprint of the wicker wall panel still on the reverse side. Wells were dug within the enclosed area to provide fresh drinking water, one of which was found inside the courtyard of what may have been one of the tribune’s residences. The well was notable for the wooden slats that lined it to a depth of 5 metres (16.4 feet) and the remains of a 1.26 metre (4.1 feet) long ladder found in it. Latrines fed with water tanks have been identified within the ramparts and examinations of the organic matter reclaimed from them have revealed evidence of the inhabitants’ diet. Among the staples of wheat, lentils and millet were seeds from apples, raspberries, figs and olives, as well as hazelnuts, and astonishingly, peppercorns that had been imported from India. Drusus’ commissariat had thought of everything.

The second fort Drusus ordered was erected on territory belonging to the Chatti, the location of which has also been the subject of long debate, but none has yet been identified in Hessen and confidently dated to 11 BCE. Wherever these two forts actually were, contingents of the Roman army now remained in Germania. It was the first time in recorded history that Roman troops spent a winter on the right bank of the Rhine. For the men continuing on to the Rhine, the march remained dangerous and the ambuscades and hit and run attacks did not let up. By now the Sugambri had withdrawn from their war against the Chatti and had returned to their homesteads. As the Romans entered and passed through their territory the Germans harried the unwelcome intruders. They too could have delivered a crippling blow, but did not. Exhausted by their inconclusive war with their neighbours, they still had to prepare for the winter ahead. Drusus’ luck held up and his men finally reached the Rhine River and made it to the safety of their camps.

Drusus now returned to Lugdunum. There he would have met with his princeps praetorii and received a full briefing on the situation in the Tres Galliae. In particular Drusus would have been concerned with the results of the census and the mood of the population following the measures taken the previous year to douse cold water on the smouldering embers of rebellion. That there is no further mention in the Roman historians of discontent among the Gallic nations during this time suggests their mood was one of acceptance, even if it was grudging. In one important respect, Drusus was now seen to be doing something definitive that would benefit all Gaul: he was dealing with the Germanic menace. The reports flowing back from across the Rhine of his military successes over the Germanic tribes would have helped boost confidence among the Gallic people that security in the homelands would improve. The fact that Romans were actually encamped in Germania during the winter of 11/10 BCE provided tangible evidence of progress in the war.

The return to Lugdunum also provided Drusus with a long overdue opportunity to be with his family again. He was still very much in love with Antonia. Drusus’ sexual fidelity to his wife was highlighted by Valerius Maximus in his Memorable Sayings and Doings as an example of abstinence (abstinentia) and continence (continentia). His eldest son was now four years old while his daughter was two. But it was a short stay. With winter setting in, and travel becoming more difficult as the weather deteriorated, they could not stay long in the Gallic capital. In November just before his departure from Lugdunum and his arrival in Rome, or somewhere in between, their next child was conceived.

On arriving in Rome, Drusus faced a full agenda. Augustus required a complete update on the second year of the war in Germania. With Agrippa dead Augustus now relied completely on Drusus and his brother to execute his military operations. While he was generally pleased with progress, however, he did not allow Drusus to accept the title of imperator that the men of the legions had bestowed upon him on the battlefield. As the acclaimed commander was entitled to add the honour after his name, perhaps Augustus felt this form of recognition was too high a profile for the young man so early in his career; or he may have preferred that he be the one to decide the moment when to grant use of the title. Neither was it the first time a commander had been blocked from accepting the title: in 29 BCE Crassus, proconsul of Macedonia, was granted a triumph, but Augustus alone took the salutation as imperator. In a repeat of this episode, Augustus took this latest acclamation again for himself to bolster his own military prestige and, just as eighteen years before, Augustus granted Drusus instead an ovatio, a lower grade of triumph in which he was permitted to ride on horseback through the city of Rome. This was tantamount to saying to Drusus that he still had work to do to earn a full triumph, but the ovatio would in the meantime give him deserved public recognition. If and when the ovation took place is not recorded. Nevertheless, Nero Claudius Drusus’ currency was rising.

Meanwhile, Tiberius had successfully subdued the rebellions in Illyricum and Pannonia. With peace breaking out across the world, it seemed an appropropriate time to shut the doors of the Temple of Ianus Geminus, an act only carried out when Roman arms were laid to rest. The last year it had happened, and that for only the third time in Roman history in fact, was after Actium when Augustus invoked the ancient ceremony on 11 January 29 BCE. The senate willingly voted and approved the motion. However, it was not to be. The pax Romana was not so easily won. The Dacians invaded Pannonia and the Illyrians rose up again in protest against the tribute imposed on them. Yet again, Augustus looked to Tiberius to fix the problem and he would spend the following year quelling them.

While in Rome, Drusus’ mother-in-law unexpectedly died. Octavia was 60, a respectably old age by Roman standards. Her body was laid in state with a curtain over her corpse at the Temple of Iulius in the Forum Romanum. Drusus gave the funeral oration from the rostrum just in front of the senate house on behalf of the family. He and his brother were pallbearers during the public funeral. Significantly Augustus did not agree to allow all the honours the senate voted her. Refusing honours as much as accepting them was one of the ways Augustus carefully managed the public image and reputation of his family in the eyes of the senate and Roman people.

For reasons good and bad, it had been a landmark year. Yet Drusus’ mind was on matters far from Rome. Perhaps inspired by the consuls of old or the lure of military glory, Drusus was intent on leaving the city at the earliest opportunity to continue the war.