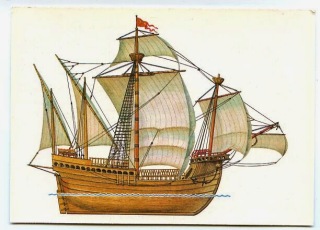

Venetian carrack

Bernard Doumerc

By the beginning of the sixteenth century, the reconciliation of economic policy with the constitution as well as with the defence of a colonial empire was no longer appropriate. Then, it was said, ‘the whole navy is devoured by the army’ and numerous voyages of merchant galleys cancelled at the last moment or diverted from their course put an end to the trust of the Venetian merchant partners.31 Henceforth, the fleet of the state, giving priority to the defence of empire, could no longer play a leading role in trade. Venice remained the maritime power that it had always been, but was no longer a first-rank naval power. One after another the sailing routes closed at the turn of the sixteenth century: the Barbary Coast, then Aigues Mortes, and finally Flanders.32 Only the Levant routes continued to be active but even those suffered long interruptions in their traffic. The disaster of 1484 was fresh in everyone’s mind; in that year, French pirates had attacked the muda of Flanders. The consequences were dreadful. The galleys had been captured after a hard fight. A hundred and thirty sailors were killed, three hundred wounded, and, of course, their cargos had been confiscated by King Charles VIII’s representative. A few months later, a major incident provoked a panic around the Rialto, the financial centre of the city. To save the last bit of the Languedoc spice import market, the Senate demanded that the Aigues Mortes convoy depart, knowing that another interruption in shipping would sound the death knell of any claim to trading in that region. It took six auctions before one was successful, and the patroni were able to extract important fiscal advantages from the government for the voyage including the payment of a 3500-ducat subsidy for each patrono and a 30 per cent increase in the charter rate. The voyage was an exceptionally long one because it included stops along the Barbary Coast. This course full of pitfalls made martyrs of the sailors and merchants. When they had returned, the accounts told the story. The cost of stopping for forty-five days to defend Zara, which was besieged by the Turks, was estimated at 10,000 ducats per galley, due to expenditures for the supplementary purchase of victuals for the crews and the payment of higher wages than had been foreseen. The patroni also asked for 8000 ducats for the lack of profit on lost charters and unsold merchandise. All this added up to an indemnity of 25,000 ducats for each patrono who had been forced to make this voyage against his better judgement.33 The government faltered because, in a backhanded way, the difference of opinion at the heart of the system of managing the galley fleet was expressed virulently in debates at the meetings about the accounts.

A census of the naval forces undertaken in 1496 by the Ministers of the Marine (Savii ai Ordini) demonstrated the naval inferiority of the Republic ‘because there are too few armed ships at sea’. This explanation given by the chronicler, Marino Sanudo, is astonishing because, he adds, ‘there are few ships because, until now, we had no fear of the Turks’.34 The result was that the obligations imposed upon the captains of the mude increased continually. In 1496, for example, the galleys of the Barbary Coast convoy participated in a massive counter-attack, launched to limit the audacious actions of the Barbary pirates.

Two dramatic episodes permit an evaluation of the interventionist role of the Venetian government in the management of the fleet. The first concerns the conflict involving the kingdom of Naples during the Italian Wars. In 1495, a league including Venice, the Duke of Milan, the Pope, and the king of Aragon, wanted to oppose the plan of the French king, Charles VIII, to annex a part of southern Italy. The Senate issued a general requisition order ‘to retain all ships and large merchant galleys’. The Captain General of the Sea, Marco Trevisan, could, with great effort, assemble a war fleet of only about twenty galleys. That is why the contribution of eleven merchant galleys was absolutely necessary, so he waited for the arrival of galleys from the Dalmatian cities. The second episode, with more tragic consequences, was that of the Battle of Zonchio in 1499. The animosity between Antonio Grimani, the Captain General and the patroni of the merchant galleys led to a catastrophe in which the disheartened crews’ weariness and the merchants’ rebellion caused a military disaster. Some months later, outside the port of Modon, which was besieged by the Turks, the patroni of the galere da mercato, by their unforgivable refusal to fight, caused the loss of the city. Despite sensational court proceedings and some sentences based on principle, the patroni were absolved since the state was willing to acknowledge its share of the blame because of the incompetence of its representatives in the battle.35 Naval battles in the following years offered further proof of the problem. During the spring of 1500 off the island of Cephalonia Captain General Marco Trevisan, warned by Grimani’s unhappy experience, considered sending back the merchant galleys that he had received as reinforcements because they seemed poorly equipped to fight, and the patroni were outspokenly critical of their mission.36 The weariness of the demoralised crews and the condemnation of the patroni of the merchant galleys, little involved as they were in safeguarding the stato da mar, heralded the end of an exemplary system. The redefinition of the specific role of the muda del mercato had not taken place because of the lack of a clearly expressed political will. Contrary to what had happened in the middle of the Trecento, this crisis of confidence in the Cinquecento quickly turned into open opposition.

In this way it is possible to discern the main lines of power that lead the Republic of Venice to dominate a large portion of the Mediterranean. The senatorial nobility, uniting the most important investors and committed merchants in the maritime economy, patiently forged a tool without equal among the rival nations and competitors: the system of regular navigation routes plied by convoys of merchant galleys. The modest ship-owners, nobles or not, were discouraged by the regulatory and fiscal obstacles that favoured the mude and by the permanent insecurity of sea-borne commerce, but were powerless to compete efficiently against the mixed private and public management of the naval potential. This was all the more true when raison d’État generated an indisputable argument for the use of these convoys, at times in the form of five galleys with 1200 men in each crew ready to intervene quickly in any zone on missions in the public interest. At the end of the fifteenth century and especially at the beginning of the following century, this senatorial nobility, united into the ‘Party of the Sea’, even after having gained considerable advantages, often in violation of the law, was no longer able, considering the circumstances, to protect their essential prerogatives. The nation, threatened by sea and by land, no longer gave priority to this system which for two hundred years had given glory and fortune to those who lived around the lagoon. This was the beginning of the downfall of the Venetian colonial empire in the Mediterranean and, at the same time, of this unique and long-effective system of operating the merchant marine.

31 Girolamo Priuli, Diarii (diario veneto), ed. A. Segre, in Rerum Italicarum Scriptores 24, 2nd edn (Citta di Castello, 1912–1941), 39.

32 Sanudo, Diarii., I, column 302.

33 Priuli, Diarii, 273.

34 Sanudo, Diarii, I, column 30.

35 Ibid., IV, columns 337, 360.

36 B. Doumerc, ‘De l’incompétence à la trahison: les commandants de galères vénitiens face aux Turcs (1499–1500)’, in Félonie, trahison, reniements au Moyen Âge, Les Cahiers du Crisima, 3 (Montpellier, 1997), 613–34, and F. C. Lane, ‘Naval Actions and Fleet Organization (1499–1502)’, in J. R. Hale, ed., Renaissance Venice (London, 1973), 146–73.