Expanding his navy was actually easier for Alexander than might have been expected. Because most of his recent conquests and alliances had involved maritime powers, his new friends were willing to contribute to his fleet-building efforts. According to Arrian, Cyprus sent 120 warships to Alexander, while both Sidon and Rhodes contributed some triremes, and “about 80 Phoenician ships joined him.”

Both Gerostratus and Enylus, the kings respectively of Aradus and Byblos, “ascertaining that their cities were in the possession of Alexander, deserted Autophradates and the fleet under his command, and came to Alexander with their naval force.”

Alexander also personally joined the naval attack on Tyre, sailing with the fleet as it embarked from Sidon. His own position was at the right wing of the armada, farthest from the coast. His initial strategy had been to lure the Tyrians into a battle in the open sea.

The Tyrians had been looking forward to such a fight on the basis of Alexander’s perceived naval inferiority, but when they observed Alexander’s fleet most remained in port rather than accepting the challenge. Alexander’s flotilla managed to sink three vessels, but aside from that they were at a stalemate.

Alexander for once had the superior numbers in a naval battle, but he could not lure out his enemy. If a fight took place, it would have to be in the tight confines of one of the island’s two harbors. It was like Issus, only on water—and at Issus, it was Darius who was in too tight a space to make full use of his superior numbers.

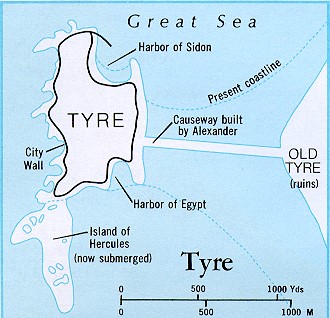

Alexander decided to blockade Tyre and wait. He assigned the Cypriot triremes to block the northern Tyrian port and dispatched the Phoenician fleet to block the southern port.

He then turned back to his land strategy, ordering the rapid construction of catapults and siege engines, including battering rams and protected towers for the transfer of troops. These were placed on ships for the final assault against Tyre’s fortifications. The Tyrians countered by building towers of their own in order to be higher than the Greco- Macedonian besiegers. It became a battle of fiery projectiles launched from higher and higher elevations.

Eventually feeling the pressure of the naval blockade, the Tyrians made an attempt to break out of the northern port using a force of seven triremes, three quadriremes and three quinqueremes. The ships moved silently so as not to alert the Cypriot blockade ships, but it would not have been necessary. The Cypriots were asleep at the tiller. Indeed, each ship was manned by a mere skeleton crew, with most hands having been quartered ashore. Catching the Cypriot fleet off guard, the Tyrians managed to sink or damage a number of vessels.

Roused from his tent—all of this happened in the heat of the summer afternoon as the officers were resting—Alexander ordered all available ships in the port on the mainland side of the channel to put to sea to prevent any additional Tyrian ships from reaching open seas. Alexander boarded a ship himself, intending as usual to lead from the front.

Despite calls from Tyrian lookouts that Alexander’s ships were pulling out from their moorings, ships continued to leave the port. Alexander’s fleet rallied, ramming and sinking a number of vessels, and capturing others.

Assault on Tyre

Finally, Alexander developed a tactical plan that called for a complex amphibious landing under fire that would be considered ambitious even by a modern combat force. In the northern part of the island, where the causeway had been built, Tyre’s walls were the most formidable and best defended, so Alexander moved to execute an unanticipated flanking maneuver by hitting a less well defended point in the southern end.

The attack would entail breaching the wall above sea level from the sea using siege engines aboard ships, and then using a portable bridge to push troops through this breach. Indeed, attacking a vertical wall above sea level is always much more difficult than putting troops across a sea-level beach using landing craft. With Tyrian defenses pierced, Alexander’s fleet would attack the two Tyrian ports simultaneously.

When his first attempt to execute the plan was quickly repulsed, Alexander withdrew, postponing a renewed attempt until a patch of stormy weather had blown through. On the third day following, the seas were quieter and Alexander resumed the assault.

After seven months, the siege finally reached its climax on the last day of the month of Hekatombaion, the same month that Alexander celebrated his twenty-fourth birthday (July 20, 332 BC). Plutarch tells that after consulting some omens, Aristander had declared confidently “that the city would certainly be captured during that month.” Because it was the last day of the month, and Tyre had held out for 200 days already, Aristander’s words “produced laughter and jesting.”

Arrian says that Alexander “led the ships containing the military engines up to the city. In the first place he shook down a large piece of the wall; and when the breach appeared to be sufficiently wide, he ordered the vessels conveying the military engines to retire, and brought up two others, which carried the bridges, which he intended to throw upon the breach in the wall. The shield bearing guards occupied one of these vessels, which he had put under the command of Admetus; and the other was occupied by the regiment of Coenus, called the foot Companions.”

When the siege engines pulled back, Alexander sent in triremes with archers and catapults to get as close as possible, even if it meant running aground, to support the infantry assault.

Again leading from the front, Alexander himself headed the assault force that went ashore. Admetus’s contingent was the first over the wall, but he was killed in action, struck by a spear. Alexander then led the Companion infantry in securing a section of wall and several towers. With Greco-Macedonian troops taking and holding a rapidly expanding beachhead, the defensive advantages of the fortified city began to evaporate.

Unfortunately for the Tyrians, their royal palace was in the southern part of the city, and it was one of the first major objectives to fall to Alexander’s invading troops. King Azemilcus, his senior bureaucrats and a delegation of Carthaginian dignitaries, who had been trapped in Tyre when Alexander’s fleet sealed the ports, were there but escaped to take refuge in the temple to Heracles. Ironically, this was the same temple at which Alexander had originally asked to be allowed to worship.

At the same time, Alexander’s fleet forced its way into the two harbors. Phoenician ships entered the southern harbor, the Port of Egypt, and the Cypriot ships breached the entrance to Tyre’s northern harbor, the Port of Sidon. Here at the Port of Sidon, the larger of the two anchorages, troops were able to get ashore inside the harbor. The defenders fell back to defensive positions at the Agenoreum, a temple to the mythical King Agenor, but were quickly routed. Alexander now had beachheads on either end of Tyre and the Tyrian defenders in a pincer.

Within a matter of hours, after a bloody siege of seven months, troops from both landings linked up in the northern part of the city. All of the defenses that had been erected on the causeway side were for naught.

According to Diodorus, immediately after his victory Alexander ordered the causeway broadened to an average width of nearly 200 feet and made permanent, using material from the damaged city walls as fill.

The causeway is still there, although it if you visited it, you would not notice it. Over the past 2,300 years, wave action and drifting sand have caused it to grow into a broad isthmus about a quarter of a mile wide. The part of Tyre that was an island in 332 BC has been connected to the mainland ever since Alexander’s day.

Alexander gave no quarter to those he captured, killing them on the spot or eventually selling them into slavery. According to Arrian, the defenders suffered about 8,000 killed or executed and 30,000 made slaves, while the Greco-Macedonian force lost 400 killed in action during the entire siege. Curtius reports 6,000 Tyrian troops killed inside the city walls, and 2,000 executed in the aftermath. While these numbers were probably stretched in favor of Alexander, many later scholars, including Botsford and Robinson, repeat them. There is no way of knowing for sure.

In any case, Alexander walked into the Temple of Heracles around sundown that day to make his long-postponed sacrifice. It was the afternoon of the last day of Hekatombaion. Of all those who had laughed at Aristander for his outlandish prediction, none were laughing now.

Alexander spared King Azemilcus and gave amnesty to all those hiding in the temple when it was captured. The sight of his city’s resounding defeat, and of Alexander standing in the temple that he had once asked to visit peacefully, was probably punishment enough for the king.

After the Battle of Issus and the siege of Tyre, Persia was no longer a Mediterranean superpower. Having had the heart ripped out of his army, and the bases ripped away from his navy, Darius would be unable to challenge Alexander significantly again until his army was deep inside the interior of the Persian Empire.