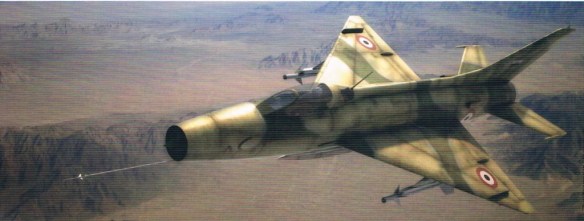

Egyptian MiG-21

Fighter aircraft and their ability to secure air superiority were of decisive importance to the course and outcome of the Arab-Israeli wars. Initially, Israel and the Arabs employed surplus World War II fighters, but both sides quickly sought modern jets. Israel bought fighters mainly from Britain and France until 1967 and then afterward from the United States. The Arabs principally obtained their fighters from Britain until 1955 and thereafter from the Soviet Union.

Arab and Israeli fighter technology largely depended on the willingness of external suppliers-Britain, France, the United States, and the Soviet Union-to provide their clients with the latest systems. Airframes, engines, avionics, sensors, and weapons improved continuously over the course of the Arab-Israeli wars. Initial jet aircraft such as the Meteor, Ouragan, and Vampire were straight-winged aircraft aerodynamically similar to propeller-driven fighters. They operated at high subsonic speeds with optical gunsights and mechanical control systems. The next development was the sweptwing transonic fighter-such as the MiG-15/17, Mystere, and Hunter-that operated close to the speed of sound.

These were quickly superseded by fighters such as the Super Mystere and MiG- 19 that were capable of level supersonic flight. Next appeared the truly supersonic fighters, such as the Mirage III and the MiG-21, typically armed with air-to-air missiles. Then, supersonic fighters such as the Phantom, Mirage V, MiG-23, and the later model MiG-21 appeared with greatly improved avionics, sensors, heads-up displays, and a wide range of air-to-air and air-to-surface munitions. The final generation consisted of agile supersonic fighters such as the F-15 and F-16, which were capable of both great speed and high maneuverability. These aircraft had advanced radars and flight controls and employed diverse precision air-to-surface weapons.

Fighter technology, though not unimportant, was less critical to Israeli success in air combat than superior leadership, organization, training, and individual initiative. Israeli pilots continuously practiced their close-quarters air-to-air combat skills (dogfighting), and that training repeatedly proved its value.

Egyptian Fighters

In the early 1950s, Egypt transitioned from propeller-driven to jet fighters. Britain sold some Gloster Meteors and de Havilland Vampires to Egypt, but Britain and the United States refused to sell Egypt advanced weapons. Egyptian president Gamal Abdel Nasser then turned to the Soviet bloc. In 1955, the Soviets agreed to supply Egypt with Mikoyan-Gurevich fighters and Ilyushin bombers, which were superior to anything in Israel’s arsenal. When the October 1956 Suez Crisis began, Egypt had 120 MiG-15s, some MiG-17s, 50 Il-28s, and 87 Meteors and Vampires. Egyptian MiG pilots were not yet fully trained, and the combined British, French, and Israeli Air Forces were superior in numbers and quality. Nasser decided to withhold his pilots from combat, and as a result, his air force was largely destroyed on the ground.

Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-15.

The swept-wing Soviet MiG-15 was still relatively new in 1956. It had excellent acceleration and rate of climb but poor control at high speed, poor stall characteristics, and an outmoded gunsight. Egypt operated the MiG-15 and MiG-15bis as well as the two-seat MiG-15UTI trainer from 1955 until 1982. A Soviet copy of the Rolls Royce Nene engine, provided by Britain to the Soviets in 1946, powered the MiG-15, which had a 688-mph maximum speed and a 50,900-foot ceiling. Range was 826 miles on internal fuel. The aircraft weighed 8,115 pounds empty and 11,861 pounds loaded. Originally designed to intercept American bombers, the MiG-15 was heavily armed with two 23-mm cannon and one 37-mm cannon. The MiG-15 (and its successors, the MiG-17 and MiG-19) rarely carried bombs

Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-17.

This was essentially an improved MiG-15 with better wings and more power. Extremely agile and with excellent turning abilities, the MiG-17 proved a tricky adversary for ostensibly superior U. S. aircraft such as the F-100, F-105, and F-4 over North Vietnam in the 1960s. Egypt operated MiG-17F and PF models from 1956 to 1982. The MiG-17F had a 710-mph maximum speed and a 54,500-foot ceiling. Range was 913 miles on external tanks. Armament consisted of two 23-mm cannon and one 37-mm cannon. The MiG-17 weighed 8,664 pounds empty and 11,773 pounds loaded. The MiG-17PF incorporated an afterburner and radar.

Egypt’s air force was destroyed during the Suez Crisis, but the Soviets quickly replaced it. In June 1967, Egypt had 120 MiG-21s, 80 MiG-19s, and 150 MiG-15/17s. Readiness was poor, however, with only about 60 percent of aircraft operational.

Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-19.

The MiG-19 was the first Soviet fighter capable of supersonic level flight. These aircraft were difficult to fly and prone to hydraulic failures and engine fires. During the Arab-Israeli wars, Egypt flew the MiG-19F, the MiG-19PF, the MiG-19S, and the MiG-19SF variants. Egypt received 80 in 1961 and another 50-60 after June 1967 (when they were apparently restricted to providing air defense over Egypt). Egypt bought 40 Chinese-built MiG-19 variants (the F-6) in the 1980s. The MiG-19S had a 903-mph maximum speed and a 56,145-foot ceiling. Range was 430 miles on internal fuel. Armament was three 30-mm cannon. The MiG-19 weighed 11,399 pounds empty and 19,470 pounds loaded.

Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21.

First flown in 1955 and extensively exported, the delta-wing Soviet MiG-21 was superior to anything in Israel’s inventory in 1967. High thrust-to-weight gave it good acceleration and rate of climb. The MiG-21 could not turn as tightly as the MiG-17, which some pilots preferred even though the MiG-17 was subsonic and the MiG-21 supersonic. Skillful Israeli pilots could beat the MiG-21 even while flying greatly inferior aircraft such as the Ouragan or Super Mystere. During the Arab-Israeli wars, Egypt operated hundreds of MiG-21F-13, MiG-21FL, MiG- 21M, MiG-21MF, MiG-21PF, and MiG-21PFM interceptors as well as training and reconnaissance versions. Egypt bought 100 Chinesebuilt MiG-21F-13 fighters (the F-7) in the 1980s. The MiG-21F-13 had a 1,350-mph maximum speed and a 50,000-foot ceiling. Range was 808 miles on internal fuel. Armament consisted of one 20-mm cannon and two Vympel K-13 air-to-air missiles (a Soviet copy of the American AIM-9 Sidewinder). The MiG-21 weighed 10,979 pounds empty and 19,014 pounds loaded.

The MiG-21PF had a 1,350-mph maximum speed and a 50,000- foot ceiling. Range was 963 miles on internal fuel. Armament was the same as the MiG-21F-13. The aircraft weighed 11,587 pounds empty and 20,018 pounds loaded.

Most Egyptian aircraft were destroyed on the ground in June 1967, but again the Soviets replaced them. By October 1973, Egypt had 210 MiG-21s, 100 MiG-17s, and 110 bomber and ground-attack aircraft, although many were unserviceable. After the Yom Kippur War, Egypt and Israel reached a peace agreement and have not met in aerial combat since then.

Syrian Fighters

During the Israeli War of Independence (1948-1949), Syria operated no fighters per se. It bought several dozen Fiat G. 55s, 10 Macchi C. 205s, 20 Supermarine Spitfires, and 23 Gloster Meteors (T. 7, F. 8, FR. 9, and NF. 13 models) in the 1950s. These never saw combat. After Egypt obtained Soviet arms in 1955, Syria requested Soviet military assistance. Syria operated the MiG-15bis from 1955 to 1976 as well as the two-seat MiG-15UTI trainer. Syria began receiving the MiG-17F in 1957, the MiG-17PF in 1967, and the MiG-19S and MiG- 19SF in 1963. Accidents and maintenance problems kept Syria’s operational inventory low.

Syria flew hundreds of MiG-21 interceptors during the Arab-Israeli wars. It received the MiG-21MF, the MiG-21F-13, and the MiG-21PF in the 1960s; the MiG-21PFM in the 1970s; and the MiG- 21SMT in 1983. It also operated training and reconnaissance versions. Syria still flies the MiG-21 today Syria had 36 MiG-21s, 90 MiG-15/17s, and some MiG-19s at the beginning of the Six-Day War. Few aircraft were operational, and few pilots were well trained. At least 58 Syrian fighters were destroyed, mostly on the ground. The Soviets quickly replaced these losses. Syria began the Yom Kippur War with 200 MiG-21s and 120 MiG-17s and lost 179 aircraft during 19 days of intense combat. After the war Syria remained Israel’s enemy, and again the Soviets replaced lost Syrian equipment. Prior to the final major clash with Israel in 1982, Syria received Soviet MiG-23 and MiG-25 fighters.

Jordanian Fighters

Jordan created its air force in 1955. Its first fighters were 20 British Vampires (10 FB. 9 and 7 F. 52 fighters and 3 T. 11 trainers), but they never saw combat. Before the Six-Day War, Jordan acquired British Hawker Hunters and had taken delivery of U. S. F-104 Lockheed Starfighters. However, the American F-104 pilots flew them to Turkey before the war began. After 1967, Jordan played no further direct role in Arab-Israeli air combat.

Hawker Hunter.

The Hunter, Britain’s first transonic fighter, first flew in 1951 and was widely exported to Middle Eastern air forces. Hunters had excellent flying qualities and were very agile and ruggedly built. From 1958 to 1968, Jordan bought 15 F. 6 interceptors, 16 FGA. 9, and 23 FGA. 73 ground-attack aircraft; 2 FR. 10 reconnaissance aircraft; and 3 T. 66 trainers. It retired them all by 1975. In June 1967, Jordan’s 22 Hunters were destroyed, after which Jordanian pilots flew Iraqi Hunters. The F. 6, with Rolls Royce Avon engines, had a 623-mph maximum speed and a 51,500-foot ceiling. Range was 1,840 miles with external tanks. Armament consisted of four 30-mm cannon and up to 7,400 pounds of ordnance on four pylons. Hunters could carry four air-to-air missiles, but Jordan did not have these weapons in 1967. Hunters weighed 14,122 pounds empty and 17,750 pounds loaded.

Iraqi Fighters

The Iraqi Air Force played a minor role in the Yom Kippur War. Four British-built Hawker Fury fighters flew a few armed reconnaissance sorties over Israel from Syria before hostilities ended. In the 1950s, Iraq obtained British Vampires, 12 FB. 52 fighters, and 10 T. 55 trainers. All were retired in 1966. Iraq began buying British Hawker Hunters in 1958 and ultimately obtained 15 F. 6 interceptors, 42 FGA. 59/59A ground-attack aircraft, 5 T. 69 trainers, and 4 FR. 59B reconnaissance aircraft. (The FGA. 59 and FR. 59B were F. 6 airframes modified for ground-attack and reconnaissance, respectively.)

In 1958, a postcoup Iraqi regime requested Soviet military assistance. As a result, Iraq received perhaps 20 MiG-15bis, 30 MiG- 15UTI trainers, and 20 MiG-17F in 1958-1959. Iraq also received 50 MiG-19S in 1960. Starting in 1963, Iraq received MiG-21F-13s, MiG-21PFs, MiG-21PFMs, MiG-21MFs, and MiG-21UTIs, although exact numbers are unclear. The Iraqi Air Force frequently led coup attempts from 1958 to 1973, and the resulting purges of its pilots reduced Iraqi Air Force effectiveness. An Iraqi pilot with his MiG- 21 defected to Israel in 1966, allowing the Israelis to analyze the aircraft’s capabilities.

Iraq had 88 fighters when the Six-Day War began but suffered from severe readiness problems. Iraq’s participation in the war was modest and involved a bombing raid launched against Israel. Hunters in western Iraq managed to shoot down 3 Israeli aircraft. In the 1973 Yom Kippur War, Iraq deployed 12 Hunters to Egypt along with 20 Hunters, 18 Sukhoi Su-7BMK attack aircraft, 18 MiG- 21PF, and 11 MiG-21MF fighters to Syria. Iraq lost 21 aircraft but shot down 3 Israeli aircraft.