Malta had already become an offensive base for the Fleet Air Arm and the Royal Air Force; in 1941 it became a base for submarines. This was not without its difficulties, since most of the necessary supplies had been taken to Alexandria, but submarines operated from Gibraltar to Malta overloaded with torpedoes and other equipment until stocks were built up. Submarines were also set to become an important link in the attempts to supply Malta.

Throughout 1941, Malta continued to develop its offensive capability, helped in February by the arrival of the first of a new class of submarines, the U-class, while Grand Harbour also was the base for four destroyers. The destroyers were more powerful ships than earlier classes, marking the continuing evolution of the destroyer from the relatively small torpedo-boat destroyer of the early years of the century to a ship with broader potential, and included the ‘J’-class fleet destroyers, HMS Janus and Jervis, and the Tribal-class fleet destroyers Mohawk and Nubian.

The clear waters of the Mediterranean had proved fatal for larger submarines, but the new U-class of smaller submarines was better suited to the Mediterranean, and of these, nine were deployed to Malta; Undaunted, Union, Upholder, Upright, Utmost, Unique, Urge, Ursula and Usk. The first two, Usk and Undaunted, nevertheless, did not survive long, but their place was soon taken by others of the same class. In addition to attacking Axis convoys and warships, these submarines were also ideal for landing raiding parties on the Italian coast, and on one occasion wrecked a railway line along which trains carrying munitions for the Luftwaffe bases in Sicily travelled.

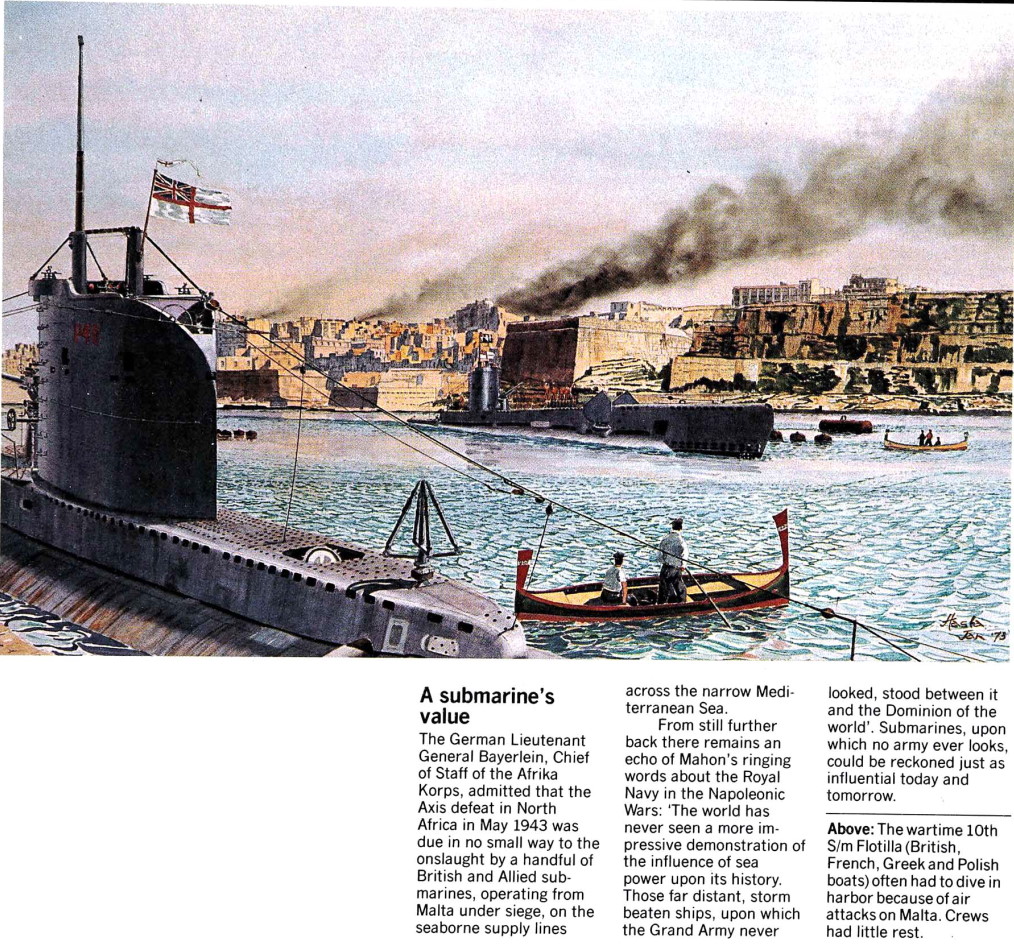

The submarines were based at Manoel Island, which lay in the Marsamxett Harbour and was approached by a causeway just off the main road to Sliema, the island effectively dividing Sliema Creek from Lazzaretto Creek. Originally a fort designed to protect the outskirts of Valletta, which towered over the other side of the harbour, Manoel Island was now a naval base, with workshops and accommodation for resting submariners and for the artificers, the Royal Navy’s skilled tradesmen. The submarines were moored alongside. Substantial AA defences were placed on Manoel Island, but being on the other side of Valletta from Grand Harbour did not spare the base from heavy aerial attack, and at the worst of the raids, the submarines found it safer to rest on the bottom, fully submerged.

The Malta-based submarines and Swordfish embarked on a campaign to sever the Axis supply lines between Italy and North Africa. The favoured hunting ground for the submarine commanders was the area off the Kerkenah Bank, even though it was heavily mined and contained many natural hazards to safe navigation. On the plus side, the Italians could only listen using hydrophones, but had nothing as effective as the British sonar, known at the time as Asdic, and also lacked radar. The campaign started in February 1941 with offensive patrols by Unique, Upright and Utmost. The first significant operation was in late February, when Upright, commanded by Lieutenant E. D. Norman, sunk the Italian cruiser Armando Diaz, one of two cruisers escorting a large German convoy. No doubt the Italians had committed two cruisers to this role to put on a show for their allies, but there were no major British warships in the area, and the cruiser, which posed no threat at all to a submarine, proved an ideal target. The effect on British and Maltese morale can be imagined!

Reconnaissance reports of large-scale shipping movements, received on 8 March, resulted in these three boats being sent to sea, even though Utmost, commanded by Lieutenant Commander C. D. Caylet, had only been in harbour for twenty-four hours. Despite this, the following day, Utmost found and sank the Italian merchantman Capo Vita. On 10 March, Unique sank another merchantman, the Fenicia. Later in the month, these submarines were at sea again, with Utmost finding a convoy of five ships on 28 March, and torpedoing and sinking the Heraklia while the Ruhr had to be towed into port. The return voyage for the depleted convoy was no less eventful, when Upright torpedoed and severely damaged the Galilea, reported as being a straggler.

April saw Upholder join the flotilla, and for almost a year she, and her commander, Lieutenant Commander Malcolm Wanklyn, played havoc with the Axis convoys. From April 1941 to March 1942, this one submarine accounted for three large troop-carrying liners each of more than 18,000 tons, seven other merchant ships, a destroyer and two German U-boats, as well as damaging a further cruiser and three merchant ships. The first two troop-carrying liners had been in a convoy of three approached by Wanklyn steering on the surface, who then skilfully fired a spread of four torpedoes at the ships. Two of the troopships managed to zigzag into the path of the torpedoes, with one sinking immediately, leaving the other to be finished off by Wanklyn when he returned the following morning. Ursula missed the third troopship, which managed to reach Tripoli safely. For his time in the Mediterranean, Wanklyn was awarded both the Victoria Cross, the highest British service decoration, and the DSO. It was a sad day when Upholder was lost off Tripoli with all of her crew in April 1942.

For a period of about a year, the Malta-based submariners exacted a high price from the enemy, but opportunities could be missed. Probably more than any other type of warship, submarines need to practise ‘deconfliction’, largely because of the difficulty of recognizing other submarines. ‘Deconfliction’ is the deliberate separation of friendly forces. In British submarine practice, this meant placing submarines to operate independently within designated patrol zones known as billets, and any other submarine found in that area was to be regarded as hostile. Yet, off Malta there were often so many British submarines that it was necessary to impose an embargo on night attacks on other submarines because of the difficulty in accurate recognition.

During the early hours of one morning in 1942, HMS Upright was on the surface when her lookouts spotted another larger submarine on a reciprocal course, and it was not until they passed that they realized that the other submarine was a large U-boat. A missed opportunity! Of course, there were many U-boats off Malta at the time, and no one will ever know if the Germans were working to the same rules, or whether their lookouts failed to spot the smaller British submarine!

The Magic Carpet

The idea of using submarines to carry supplies was not new – it dated from the First World War when the Germans had established a company to operate merchant submarines to bring much needed strategic materials from the United States and bypass the increasingly effective British blockade of German ports. The siege of Malta presented an opportunity for British submarines to show what they could do, carrying supplies on what became known as ‘Magic Carpet’ runs. At first the Axis grip on Malta was relatively light, and losses on the early convoys were few and far between, but by 1941, the situation was increasingly difficult, and it became the practice for every submarine heading to Malta from both Gibraltar and Alexandria to attempt to carry at least some items of stores in addition to their usual torpedoes or mines. The ‘Magic Carpet’ submarines, however, were the larger submarines, and included the minelaying submarines Rorqual and Cachalot, the fleet submarine Clyde and the larger boats of the O, P and R classes. The tragedy was that had not an unfortunate accident deprived the Royal Navy of its sole aircraft carrying submarine, M2, some years before the war, that boat’s hangar would have made an ideal cargo hold. In fact, the Royal Navy could have used the French submarine Surcouf, a large 2,800 ton boat also with a hangar, but never did so even though she was with the Free French rather than Vichy forces. Some have surmised that doubts over the reliability of her crew might have been behind this failure, but it is more likely to have been a failure of the imagination, since the crew could have been taken off and a British one installed – but in any event, Surcouf was lost in the Caribbean.

The Porpoise-class minelayers and Clyde were especially effective as supply ships, with plenty of room between their casing and the pressure hull for stores while sometimes one of the batteries would be removed to provide extra space as happened on Clyde on at least one occasion, and the mine stowage tunnel was a good cargo space. Rorqual on one occasion carried twenty-four personnel, 147 bags of mail, two tons of medical stores, sixty-two tons of aviation spirit and forty-five tons of kerosene. Inevitably, there was much unofficial cargo, a favourite being gin for the wardrooms and messes in Malta, and even Lord Gort, Dobbie’s successor as governor, was not above having a small consignment of gramophone records brought out to him in this way. Cargo was sometimes carried externally in containers welded to the casing.

The operation was not without its problems and the size of cargo that could be carried, while impressive in itself, could never compare with that of an average merchant ship, at this period around 7,500 tons. This was a measure of the desperation of Malta’s plight! For the submariners, there were problems with buoyancy. On one occasion Cachalot had so much sea water absorbed by wooden packing cases stowed in her casing that her first lieutenant had to pump out 1,000 gallons of water from her internal tanks to compensate. Fuel was another hazard. In July 1941, Talisman carried 5,500 gallons in cans stowed beneath her casing, and on other occasions fuel could be carried in external fuel tanks. When carrying petrol in cans, submarines were not allowed to dive below sixty-five feet, while aviation fuel in the external tanks meant that fumes venting in the usual way constituted a fire hazard, so smoking was banned on the bridge and pyrotechnic recognition signals were also banned. Another problem was that the Mediterranean favoured smaller rather than larger submarines, with its clear waters and the lack of great depths, although, of course, these submarines were always too close to the surface anyway.

One disadvantage of the convoy system is that ships come in bunches, like London buses, rather than one or two at a time when port facilities can cope easily. The submarines were free of this inconvenience, the case of feast and famine, and made supply runs once every twelve days or so.

In addition to flying her ‘Jolly Roger’ at the end of a successful patrol, HMS Porpoise added a second flag flown beneath the Jolly Roger’s tally of ships sunk – this was marked PCS for ‘Porpoise Carrier Service’, with a white bar for each successful supply run, and there were at least four for this one boat alone.

The ‘Magic Carpet’ submarines did not confine themselves to their supply runs. After unloading in Malta, they would take mines from the underground stores and proceeded north to lay them off the main Italian ports, such as Palermo, before returning to Egypt. On a number of occasions, these submarines also found and torpedoed Axis shipping, with one torpedoing and sinking an Italian submarine and then torpedoing an Italian merchantman, which stubbornly refused to sink until the submarine surfaced and sank her with gunfire.

Meagre though the capacity of the submarines might have been compared with that of cargo ships and tankers, the steady trickle of supplies did at least stave off defeat. Their work was augmented by a tenuous air link with Gibraltar, operated by the newly-formed British Overseas Airways Corporation, formed in 1940 on the merger of Imperial Airways with its lively competitor, British Airways, which operated ex-RAF Armstrong-Whitworth Whitley bombers, modified to carry supplies.