At the Casablanca Conference in January 1943 it had been determined that the threat of large-scale cross-Channel operations must be maintained against the Germans in order to give relief to Allied operations in Italy and to the Russian Front, by keeping as large a German force in France and the Low Countries as possible.

In the spring of 1943 Lt Gen Frederick Morgan, newly- appointed Chief of Staff to the Supreme Allied Commander, and his team planned a three-phase deception programme. Two of these planned deceptions were aimed at Norway and Brittany; the third was a threatened amphibious landing in the Pas de Calais, to be known as Operation ‘Starkey’.

Although essentially a ruse, the ‘Starkey’ plan was initially constructed so that it could become a real landing should conditions become favourable. The landing areas chosen were the beaches flanking Boulogne, endowing the possibility of a breakout to take the ports of Calais and Antwerp. However, a Joint Planning Staff meeting in July made it clear that ‘Starkey’ would be limited to deceptive measures, with no plans for invading the Continent. The aims of the Operation were to act as a rehearsal for the real invasion (already planned for May 1944), to deceive the enemy into thinking that invasion was imminent, and to inflict the greatest possible damage on the Luftwaffe. As the major offensive operations would be carried out by the Allied Air Forces, command of ‘Starkey’ was given to the AOC, Fighter Command, Air Chief Marshal Sir Trafford Leigh-Mallory (who would subsequently also be appointed C-in-C, AEAF).

The date chosen for this amphibious feint was 8 September 1943, but before that a large-scale movement of land forces into the embarkation areas along the South Coast took place, and landing craft and merchant ships congregated in the ports between Southampton and Dover. The Air Plan consisted of three main phases:

1. The reinforcement of 11 Group and intensification of the air offensive in the Pas de Calais (16-24 August).

2. The intensive reconnaissance and bombing of enemy airfields, military and industrial targets in the Pas de Calais (25 August-7 September).

3. a) The night bombing of the long-range coastal guns to the north and south of Boulogne on 6n and 7/8 September, followed by daylight bombing of the same targets early on 8 September.

b) Attacks on enemy airfields and communications on 8 September by heavy, medium and fighter- bombers.

c) Air umbrella over the Naval Assault Force and escorts to the bombers

It was expected that all this activity would draw the Luftwaffe into battle, much as it had at Dieppe the previous year. The air objectives were therefore the destruction of the maximum number of enemy aircraft in the air and on the ground, and the establishment of air superiority to facilitate subsequent operations against the occupied coast.

Phases 1 and 2 went much according to plan. 11 Group was reinforced by squadrons from 10, 12 and 13 Groups; the TAF transferred 83 and 84 Groups to 11 Group control, together with the five squadrons of 2 Group medium bombers which moved their bases in Norfolk to Dunsfold and Hartford Bridge. Three squadrons of anti-shipping Beaufighters also moved south, bringing total squadrons available to no fewer than 86.

Bomber Command allocated Wellingtons and Stirlings from the main force, plus OTU Wellingtons, to the night bombing campaign, while daylight raids were carried out by US Eighth Air Force B-17s and B-24s, and by the B-26 medium bombers of the 3rd Bomb Wing.

Weather conditions delayed Phase 3 by one day – ‘D-Day’ would now be 9 September, and at 0700 hours on that day 355 ships gathered off Dungeness and set course for Boulogne. Shortly before the French coast was reached, the whole convoy made a U-turn and headed back for England under the protection of smoke – partly generated by 88 Squadron’s Bostons. Not a shot was fired nor an enemy sortie flown against them. Other TAF units played their part, bombing the guns and airfields, and providing escorts.

At the end of the operation little success had been gained against the Luftwaffe, despite the huge effort – 11 Group squadrons flew more than 2,000 sorties on 9 September alone. Only a dozen German aircraft were claimed destroyed. The TAF units involved claimed two probables and a damaged for the loss of one Spitfire and its pilot, and one Typhoon was damaged.

So where was the Luftwaffe? During all the air activity it had remained virtually dormant, the only raids which it intercepted being Eighth Air Force attacks in the Beauvais and Paris areas. German fighters had been airborne during raids on Lille and St Omer, but had declined to intercept. The only other apparent reaction had been a precautionary movement of fighters from Holland and Belgium, where they were in a position to intervene if required. It seemed that the Germans had not considered the operation a serious threat (for whatever reason); neither did they wish to engage a force vastly superior in numbers, preferring to conserve their hard-pressed fighter force for defence against daylight raids on their homeland.

Valuable practice for the real invasion, just nine months away, had been undertaken and useful lessons learned. Telephone and radio communications would have to be improved and changes in strategic and tactical reconnaissance procedures were recommended. Bombing of airfields, marshalling yards and guns by the ‘heavies’ was thought to have been effective; in fact the latter targets were little damaged and the attacks had cost the lives of nearly 500 French civilians.

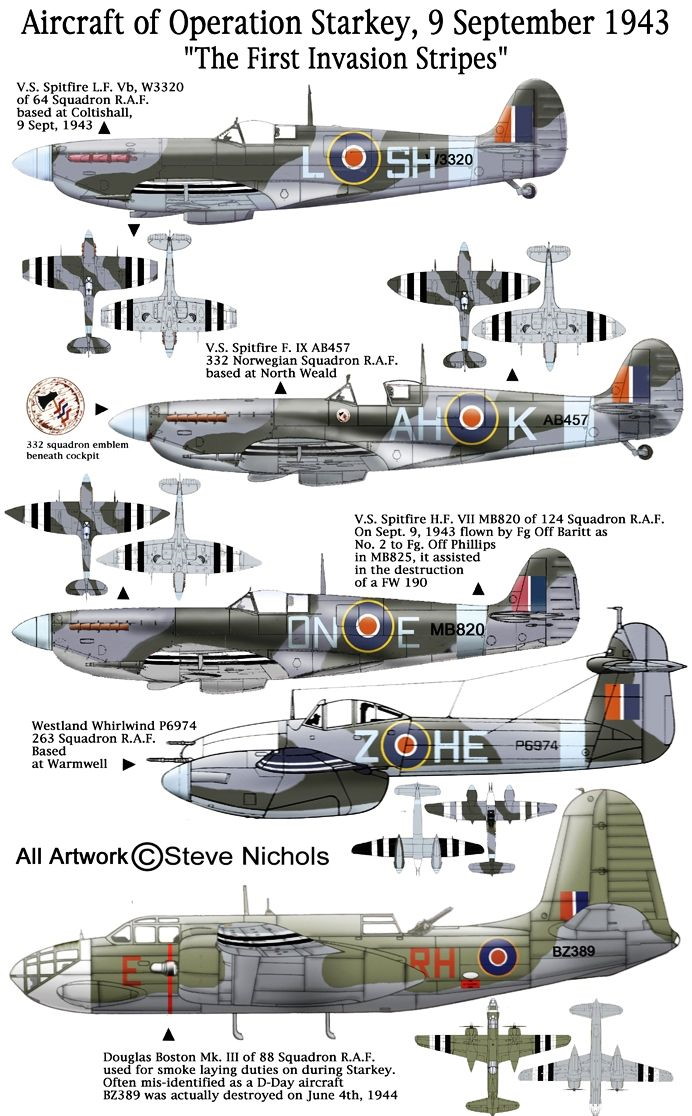

Aircraft which were undertaking low-level sorties on 9 September were required to carry special black and white markings on the wings (see diagrams overleaf). These proved very successful and were reported as ‘excellent’ by the Naval Force commander. With some modification and extension to the aircrafts’ fuselages, they would be seen again in nine months – on a considerably greater scale.

25 August 1943

In England, the US Eighth Air Force is assigned to the role of bombing important Luftwaffe targets in Operation STARKEY, designed to contain enemy forces in the west to prevent their transfer to the Eastern Front, and to serve as a dress rehearsal in the Pas de Calais, France area for the invasion of western Europe. The Allies hope to provoke the Luftwaffe into a prolonged air battle. The VIII Air Support Command flies Missions 34A & 34B against two targets in France. (1) 21 B-26B Marauders bomb the power station at Rouen at 1832 hours and (2) 31 B-26s attack Tricqueville Airfield at 1834 hours; they claim 1-8-5 Luftwaffe aircraft.

9 September 1943

On D-day for Operation STARKEY (a rehearsal for the invasion of France), the US Eighth Air Force in England dispatches a record number of 330 heavy bombers against various targets in France. (1) 20 B-17s bomb the industrial area at Paris, at 0903 hours and 48 others hit the secondary target, the Beaumont Suroise Airfield; they claim 16-2-9 Luftwaffe aircraft; 2 B-17s are lost; (2) 59 B-17 bomb Tille Airfield at Beauvais at 0816-0819 hours; (3) 37 B-17s attack Nord Airfield at Lille at 0830-0833 hours; (4) 52 B-17s bomb Vendeville Airfield at Lille at 0830-0840 hours; (5) 51 B-17s hit Vitry-en-Artois Airfield at 0837-0840; (6) 28 B-24s bomb Ft Rouge and Longuenesse Airfields at St Omer; and (7) 35 B-24s attack Drucat Airfield at Abbeville. All missions except (7) above are escorted by 215 P-47 Thunderbolts that claim 1-0-0 Luftwaffe aircraft; 2 P-47’s are lost. Operation STARKEY is a disappointment as the Luftwaffe refuses to commit fighter defenses on a large scale, thus preventing possible destruction of many of their aircraft, which Allied air forces hoped to accomplish. The US VIII Air Support Command flies Mission 55 against coastal defenses around Boulogne, France; 202 B-26Bs hit the targets at 0745-0915 hours; 3 B-26’s are lost.