Major surface operations in the Adriatic became

progressively infrequent during the last two years of the war. The increased

use of mines and the larger number of submarines operating in the sea made it

an inhospitable environment for capital ships. Minefields restricted the

Austrians’ ability not only to deploy the battlefleet but also to undertake

training. Dwindling resources and the death of the fleet commander Admiral Haus

in February 1917 only compounded this. During the war the Austrians laid around

6,000 mines. Two thirds were in defensive fields, mostly covering the

approaches to the main base at Pola. The remainder were laid off the Albanian

coast and Venice. The Italians laid around 12,000 mines in defensive fields off

the major ports, among the Dalmatian Islands and off Istria.

The loss of a significant number of battleships, the

inability to inflict a decisive defeat on the fleet and the problems in

protecting the Italian coastline led many in Italy to question the utility of

the navy. However, in the north the forces based at Venice were crucial in

protecting the seaward flank during the Austro-Hungarian offensive in the

autumn of 1917.

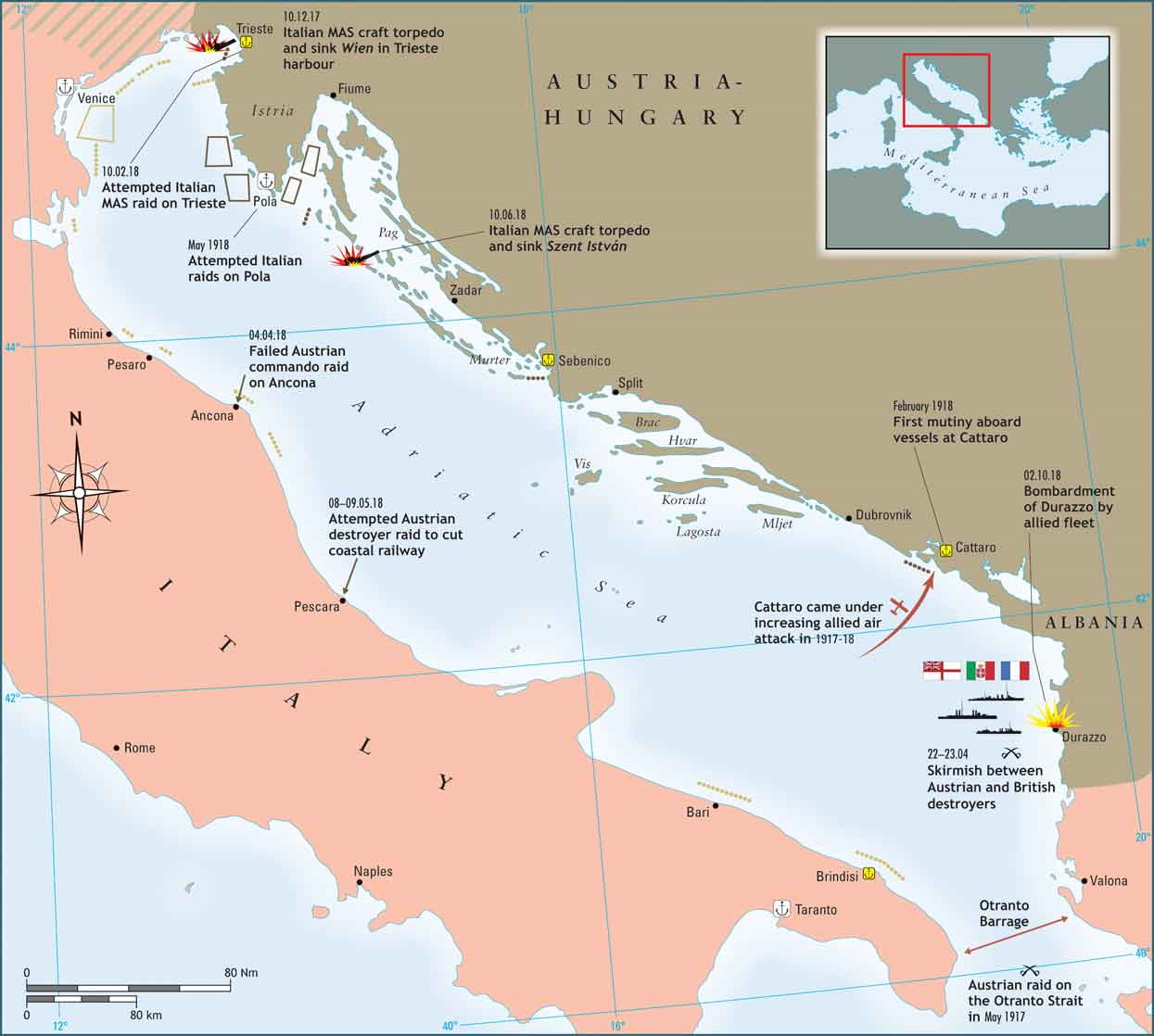

The focus of naval operations rotated around the allied defences in the Strait of Otranto. Austrian light forces repeatedly tried to interfere with these and achieved the greatest success of the war with the surprise raid on 14–15 May 1917. A few minor skirmishes between destroyers occurred throughout the spring of 1918, then a large raid involving the four modern battleships was planned for June 1918. However, as forces were assembling Szent István was torpedoed by an Italian MAS motor torpedo boat. The final allied operation of the war was a massive naval bombardment of Durazzo by a force of more than fifty warships.

#

In the autumn of 1915 the entry of Bulgaria into the war led

to a concerted Austrian-German-Bulgarian offensive that overran Serbia. The

Allied effort to assist, too little and too late, led to the establishment of

the Salonika front. The supply of this new front eventually became an onerous

responsibility because the route through the Mediterranean was exposed to the

depredations of submarines. The remnants of the Serbian army made an epic

retreat over the Albanian mountains to the coast, where, in an evacuation

similar to that of Dunkirk during World War II, they were taken to Corfu,

reorganized, and eventually brought to the Salonika front to resume the

struggle.

The Austrian navy made no serious attempt to disrupt the

evacuation although, on 29 December 1915, its ships raided the Albanian port of

Durazzo. It lost two precious modern destroyers to mines and was lucky to

escape from the superior Allied forces based at Brindisi that attempted to cut

it off. This was one of the few surface actions of any size in the Adriatic. A

stronger effort by the Austrians in the ensuing weeks might have disrupted the

evacuation, but no such attempt was made. Haus preferred to preserve his big

ships as a “fleet in being,” raising the potential cost of any Allied operation

against the Austrian coast. Action in the Adriatic remained limited to light

forces.

The Allies attempted to close the Straits of Otranto. This

took the form of a barrage established by British drifters, gradually expanded

and eventually including a fixed mine-net obstruction. It was mostly

ineffective, although in May 1917 the Austrians raided the barrage, sinking a

number of drifters. Once again a running battle ensued in which the Austrians

were lucky to escape in what was the most prolonged surface encounter in the

Adriatic during the war. In June 1918 the new and aggressive Austrian commander

Rear Admiral Miklós Horthy de Nagybána planned a raid employing the Austrian

dreadnoughts in support. It was aborted after part of his force ran into

Italian MAS (motor torpedo) boats on their way south during the night, and the

dreadnought Szent István was sunk.