Fortifications and siege works. (American

Artillerist’s Companion)

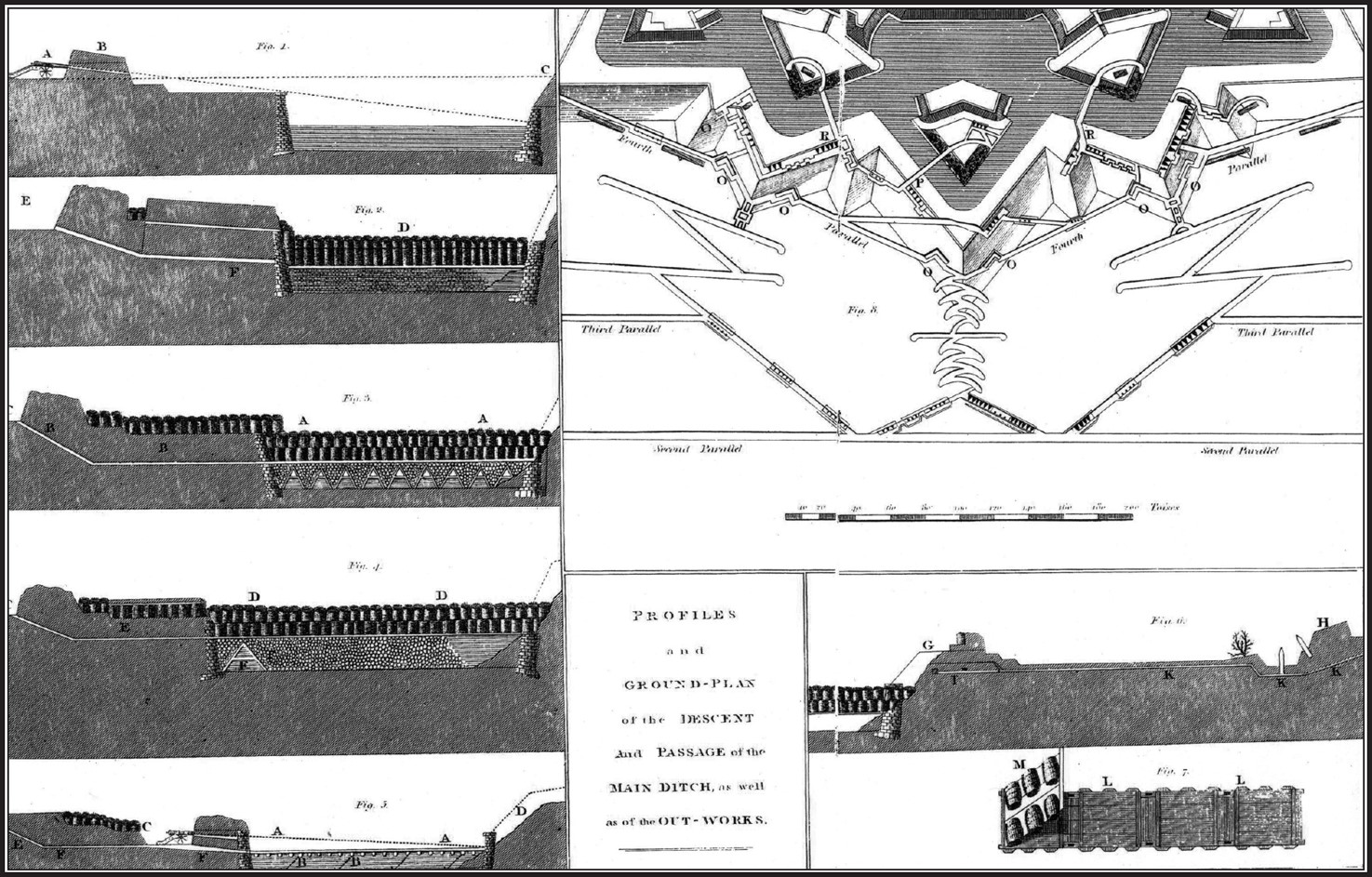

Construction of fortified bridgeheads (têtes du pont).

In the centre of the second row is an excellent representation of a horn work.

(American Artillerist’s Companion)

ESTIMATED REQUIREMENTS TO DEFEND FORTRESSES

When a man has committed no faults in war, he can only have been engaged in it but a short time.

Marshal Turenne

The ring of hammers and other blunt objects, heavy digging

of field fortifications, many times under fire, the building of gun platforms

in almost every type of terrain, including muddy, flooded ground, marked the

beginning of a siege of a fortress or a strongly fortified city or town.

Engineer officers would direct the beginnings of the siege with their templates

and instruments, calculating mathematically where to dig and, with their

brothers of the artillery, where to emplace the siege batteries to bring the

fortress under punishing fire.

Engineer troops, the sapeurs du génie and miners, would

prepare their work, the miners getting ready once again to sink their shafts

and begin their tunnels toward the fortress to their front and preparing the

mining charges that could bring down the curtain walls confronting them. The

sapeurs would don their blackened armour, cuirass and lobster helmet, that

might, or might not, protect them in the besiegers’ trenches against gunfire

from the defenders, and prepare to dig saps and parallels and perhaps lead the

infantry assaults.

With the initial saps and approaches dug, the first

batteries established with their wooden firing platforms and magazines, the

great guns would be brought into position by horse- and man-power, within range

of the opposing fortified positions to begin their relentless pounding of the

enemy positions both day and night. Siege guns, 16- and 24-pounders, coupled

with 8-inch howitzers, would blast the defenders and the great mortars, lofting

their deadly bombs over the fortress walls and into the interior would search

for the fortresses’ magazines for a lucky shot that might end the siege.

Last of all, but not nearly least, the infantry battalions,

when not engaged in digging the siege entrenchments in support of the

engineers, would wait until summoned to assault breaches made in the fortress

walls if the fortress did not capitulate before that was necessary. The ‘poor

bloody infantry’ would bear the burden, and pay the price in blood, for any

failure of the engineers, artillerymen, and the senior officers if the siege

had not been properly handled before the infantry were sent in.

With the advent of gunpowder artillery in Europe in the

fourteenth century, a balance was usually attempted, and many times achieved,

between firepower and mobility. Field artillery came into its own by the middle

of the fourth decade of the eighteenth century, pioneered by the Prussians,

with the Austrians making similar changes in the next decade. The French

followed in the mid-1760s after humiliating defeats in the Seven Years War that

clearly demonstrated the inferiority of the then-current Vallière System of

Artillery of 1732. Just about every other nation with an interest in artillery

followed suit, including the young United States upon declaring independence

from Great Britain in 1776.

Heavy artillery, however, was present from the dawn of the

arm, and that was a function both of technology, or lack of it, and the need to

have guns strong enough to punch through or partially demolish both permanent

and field fortifications. Heavy artillery is the main subject of this volume,

with its strength and lack of general mobility and inability to keep up with a

fast-moving field army being its main characteristics.

The main opponent of siege artillery was fortress or

garrison artillery, usually composed of the same guns as siege artillery, but

mounted on different gun carriages, designed to be operated inside

fortifications and to defend the position where they were emplaced.

Siege and fortress artillery also included howitzers and

mortars. The howitzers used in siege and fortress operations were of the same

general design as those assigned to the field artillery, but were larger and

heavier, with the same restrictions on movement as siege artillery guns.

Mortars were stationary artillery pieces, designed for the attack and defence

of fortified places, and ranged from small to large and generally speaking

fired explosive shell. Howitzers were something like smaller mortars, but

mounted on field carriages, and were somewhat more mobile than the mortars.

All siege artillery would be mounted in batteries supervised

and constructed by the engineers and artillery officers, and great wooden

platforms would be emplaced from which the artillery could fire from a stable

position.

Sieges were usually carefully undertaken, meticulously

planned, and were methodically carried out with the besiegers’ trenches and

batteries edging ever-closer to their targets and objective. While the

artillery rate of fire might be much slower than that of field artillery in

battle, it was relentless and would continue day and night until a breach was

made in the curtain wall or the defenders finally capitulated.

The initial siege works and artillery batteries and firing

positions completed, sweating gunners manhandled their large, awkward siege

pieces onto the firing platforms, managing to get the long gun tubes into the

embrasures cut into the field works without damaging the entrenchments.

Ammunition would be moved into the magazines constructed in the rear of each

siege battery position, dug in and protected from enemy artillery fire.

Artillery implements would be placed in each gun position, for the gun crews to

use in pointing, loading, and cleaning each piece. The gun crews were smaller

than those for field artillery, even though the heavy siege guns were both

physically larger than the field pieces, and the guns themselves were of larger

calibre.

Large mortars were emplaced in some of the siege battery

positions. Of larger calibre than even the largest of the siege guns, mortars would

lob bombs over the walls of a besieged fortress, town, or city. These were huge

compared to the ammunition fired by the siege guns – some weighing in at 200

pounds. Their crews were also smaller than those in the field artillery, as the

mortars were stationary weapons, the guns tubes emplaced in their ‘beds’ –

heavy, awkward mounts. Whereas the siege guns were on the familiar wheeled gun

carriages which could be moved as necessary, the huge-mouthed mortars would

have to be moved by specially constructed vehicles from place to place, and

then assembled in their prepared firing positions.

Together, the mortars and heavy siege guns, usually known as

‘battering pieces’ would concentrate their firepower against a pre-selected

point of the besieged place to prepare it for an infantry assault or to batter

the garrison into submission.

Fortress and Siege Fortifications and the Attack and

Defence of Places

The fate of a nation may depend sometimes upon the

position of a fortress.

Napoleon

13 October 1810, Sobral, Portugal

Chef de Bataillon Jean Jacques Pelet, first aide-de-camp to

Marshal André Massena, commander of the Army of Portugal, and his companion,

Capitaine Jean Richoux, made their way towards Sobral by taking a steep and

narrow road up to a position from where they could observe the British

fortifications that were becoming known as the Lines of Torres Vedras.

While the road had been repaired in places, it was a

difficult climb that was hard on the horses, and by the time they reached their

objective, only one of the dragoons remained and his mount had thrown a shoe.

Pelet and Richoux dismounted and were guided to the top of a hill by some

Portuguese peasants, who were, however, very closed-mouthed even as to the

names of the villages in the area.

Being an engineer, Pelet closely inspected the terrain and

noted that the French maps were inaccurate and needed to be updated. French

troops were occupying the area, and Pelet and Richoux picked up another escort,

this time of voltigeurs. These light infantrymen, often called kleine Manner

(‘little men’) in contemporary comments, were efficient and excellent escorts

for the type of terrain the two staff officers had to negotiate on their

reconnaissance.

The defences were extensive, and were manned by both

Portuguese and British troops, and they would definitely be a hard nut to crack

if Massena chose to assault them. A mixture of fortifications had been

constructed – redoubts, lunettes, redans and trenches criss-crossed the rough

terrain, and all of them appeared to be mutually supporting.

When he had seen enough, Pelet motioned for them to go, and

he and Captain Richoux with their escort of vigilant voltigeurs, made their way

back down to friendly territory. Massena would not like their report, but would

take it to heart and no doubt, as per his usual practice, he would make his own

reconnaissance. Massena was no fool. He was a good commander who could be

ruthless when need be, but he would not waste his troops in useless assaults

against what appeared to be an impregnable position.

Since the dawn of warfare, man has attempted to protect

himself and what is his with some type of fortification. Alexander and his

near-invincible Macedonians were successful in the attack of fortified

positions, be they temporary or permanent. The Romans were excellent military

engineers and understood in depth the defence and attack of places. In the

Middle Ages the fortified castle could sometimes withstand a siege, especially

if the garrison had enough provisions and access to a potable water supply. With

the introduction of gunpowder artillery in the fourteenth century, castles

could now be breached more easily, and it was gunpowder artillery manned by the

Ottoman Turks that finally defeated the walls of Constantinople in 1453,

arguably the most sophisticated defensive system up to that time, the Eastern

Romans being the capable inheritors of the Roman ability and flair for military

engineering.

Recognizing that modern artillery had rendered the older

systems of fortifications obsolete, such military engineers as Vauban and

Coehorn developed fortification systems that were lower, harder to breach, and

usually were organized and defended in depth.

There are generally speaking two types of fortifications –

permanent and temporary. Permanent fortifications usually took the form of the

large masonry defences of fortified cities and major fortresses. These required

constant maintenance because if left alone they would fall into disrepair.

Despite their imposing appearance and apparent strength and impression of

solidity, masonry and brick fortifications could be quite fragile. Temporary

fortifications took the form of earthworks, and these could be built for use on

a battlefield and take the shape of anything from a strong redoubt, to redans,

flèches, and lunettes that would be hastily constructed in a battery position

by artillery gun crews. Some temporary fortifications could be used as

semi-permanent structures, such as those used to fortify a bridgehead, or those

made in the breach of a besieged fortress after an artillery bombardment had

punched a hole in the curtain wall.

Interestingly, earthworks were also used in permanent

fortifications either to enhance the masonry works or to repair them. They were

also used to construct new defensive works during a siege to replace works that

had been breached or destroyed.

Siege works were also semi-permanent field fortifications

and were constructed of earth and wood. Siege batteries would be built of earth

reinforced with gabions or wood. Embrasures for the siege guns would be earth

reinforced with wood. and the gun platforms inside the works, essential for

stable firing positions for siege artillery, were constructed of wood.

Fortresses filled more roles than merely defensive

structures. They served as depots and magazines and would be filled with

supplies during a campaign, especially along an army’s line of communication.

They could be garrisoned by regular troops, but these would usually be

forwarded to the field army, and their place taken either by recruits or

conscripts who would then complete their training before being sent forward as

replacements when needed or requested.

Fortresses were usually ‘easy’ to defend against an

attacking or besieging army, and it was a long, tedious process for an army to

prepare to besiege a fortress, especially a fortress city. Just to invest and

surround a fortress took a large number of troops and units, and it also took

time to prepare the siege works. Many times defences had to be prepared by a

besieging army to protect itself from an army marching to relieve the siege.

Sometimes, sieges would be lifted by the besieging force having to march

against an enemy army intent on relieving the fortress, which was done during

one of the British sieges of Badajoz in 1811, resulting in the bloody battle of

Albuera between Marshal Soult’s French and British General Beresford’s British

and Portuguese.

The Fortress

When gunpowder weapons, especially artillery, were developed

in the late Middle Ages, all existing fortifications soon became obsolete. What

resulted was a new range of permanent and field fortifications which, if not

impervious to artillery fire, then at the very least made it more difficult for

artillery to breach permanent defences. The use of earthworks became more frequent

over the years, but permanent masonry fortifications were developed that would

give the defender at least a chance of withstanding modern artillery fire.

Overall, one of the best concepts of defensive works was to

construct them in depth which gave the attackers the problem of overcoming

defences in layers and in order to accomplish that mission they might incur

heavy enough casualties to cause the siege to fail.

The great objective of fortifications and the artillery that

one employs as the principal agent of their defence is to make one’s troops,

which are inferior in numbers, in morale, or in skill of manoeuvring, more able

to resist another’s troops which are superior in one or another of these

points. The success of the defence depends, therefore, on the ability of the

general, the strength of the fieldworks, the proper disposition of the troops,

and the effective use of the artillery.

Permanent defences would begin from the inside and be

constructed outward. Geometrical patterns were used to construct bastions along

the curtain wall which had interlocking fields of fire against any attacker. In

front of the curtain wall, redans would be constructed as outworks, not

attached to the bastions or curtain wall. A ditch, either dry or wet, would be

constructed in front of the curtain wall and the interlocking bastions. This

was designed to impede any infantry assault and would make the curtain wall

even taller to the assaulting infantry if they reached the ditch. The ditch

might have a palisade in the middle to impede any assault further. Inside the

main fortress, a citadel was usually constructed which was the last line refuge

for the garrison which they would fall back to if the curtain was breached and

the enemy infantry assault was successful.

How the available artillery was employed was critical to the

defence of the place:

In the case where one places the cannon at various points

in the entrenchments, it will be necessary, as much as possible, that they not

get in the way of the infantry, or diminish the execution of their fire. In the

entrenchments, as everywhere else, large batteries should not be made, because

the enemy can simply avoid them. They often lead to defeat, for they strengthen

one point of the line while weakening the rest, which can be all the more

dangerous if the number of pieces is very considerable.

Vauban also believed that artillery was critical for the

defence of a fortress and should be the main emphasis by the defenders. He also

pushed for the development and production of iron fortress pieces, as iron was

much less expensive than bronze, but his recommendations were ignored by the

Duc de Main, who was the Grand Master of the Artillery during that period.

Finally, it should be stressed that ‘The science of

fortification was by no means unknown and uncultivated long before … Vauban.’

The first publication describing a complete system of fortification was written

by Errard de Barleduc who served Henry IV, the first Bourbon king of France.

Subsequently, the Chevalier Antoine de Ville wrote a treatise of fortification

while serving Louis XIII as an engineer. De Ville’s methods were termed ‘the

French system’ and he was not only a theorist, but a practitioner. The ‘Dutch

system’ was developed by Samuel Marollois, whose writings influenced Maurice of

Nassau.

The Count de Pagan was Vauban’s ‘direct ancestor’ in the

science of siege warfare and probably served as a model for Vauban. Pagan was

both experienced and knowledgeable and his conduct of sieges during the reign

of Louis XIII was successful. Pagan’s system was ‘improved upon by Alain

Manesson Mallet, and his construction of fortification is … looked upon as the

most perfect’ and was little different from Vauban’s first system and was

probably the model for it.

Menno, Baron Coehorn, the great Dutch engineer and

contemporary of Vauban, has already been mentioned; he was at the same time

general of artillery and lieutenant general of infantry in the Dutch service.

He was also Director General ‘of all the fortified places belonging to the

United Provinces’. Coehorn was noted as being ‘intelligent and sagacious’, as

well as ‘thoroughly convinced, that, however expensively the rampart of a town

may be constructed, it could not long sustain the shock of heavy ordnance’ and

he ‘invented three different systems, by which he throws so many obstacles in

the way of a besieging enemy, that, although the place be not in reality

rendered impregnable, it is nevertheless so far secured as to make its conquest

a business of considerable hazard and expense’. It should also be noted that

Coehorn designed his systems to defend Holland, a country that is generally

flat and level and so could tailor his fortifications to that one reality.

Vauban did not have that luxury. When the two actually faced each other in the

attack and defence of places, at the siege of Namur in 1692, Vauban’s system

proved to be superior to Coehorn’s.

While fortresses were not the main focus of campaigns during

the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic periods, they were still useful in a

number of ways. Holding key fortresses in an occupied territory or country was

a constant reminder to the population at large that there was a garrison,

usually a large one, that could become hostile and a major problem in the event

of hostilities.

Occupying and maintaining fortresses in one’s own nation

provided a shield or covering force behind which the army could mobilize and

take the field. Well-garrisoned and provisioned fortresses supplied with enough

artillery could pose a major problem to an invading army, usually so much that

forces had to be left behind, or the enemy commander believed that they had to

be left behind, to invest the fortress and either nullify it or take it. This

could lead to the invading army’s strength being depleted to such a point as to

leave it too weak when it finally came up against the defending army.

Fortresses also provided a safe and sheltered environment

where recently conscripted units could complete their training before becoming

part of the field army. And those garrisons of conscripts could be a reassuring

reminder both for the native population and the enemy that the garrison could

become a hostile force if provoked. Napoleon used this approach during his

campaigns.

Coastal Defences

Coastal defences were necessary for the protection of naval

bases, ports, and other facilities deemed essential. The fortifications were

usually nothing out of the ordinary and generally followed the patterns

developed by inland fortifications other than that they also had to be able to

defend themselves against attacking ships if necessary.

One interesting development by the British was the Martello

Tower. Built on the coastline, these were round, two-storey masonry structures

with a flat roof, upon which would typically be placed one coastal defence

piece, either a naval long gun or a carronade. The piece was usually put on a

traversing gun carriage that could be pointed in any direction in a full

circle. They could be a standalone work, or be coordinated with other defensive

measures and they were built in Britain, Canada, and other places in the

British Empire. While small and usually armed with only one garrison piece,

they were quite innovative, easy to build and man, and if nothing else could

provide early warning of a naval or land attack.

Coastal defence ordnance was normally, but not always, of

the iron naval type. The gun carriages used with the ordnance could be of

several types, including the standard naval gun carriage of the truck type, the

traversing carriage, or the older slide carriage. Mortars could also be used in

the defence of ports and naval bases.