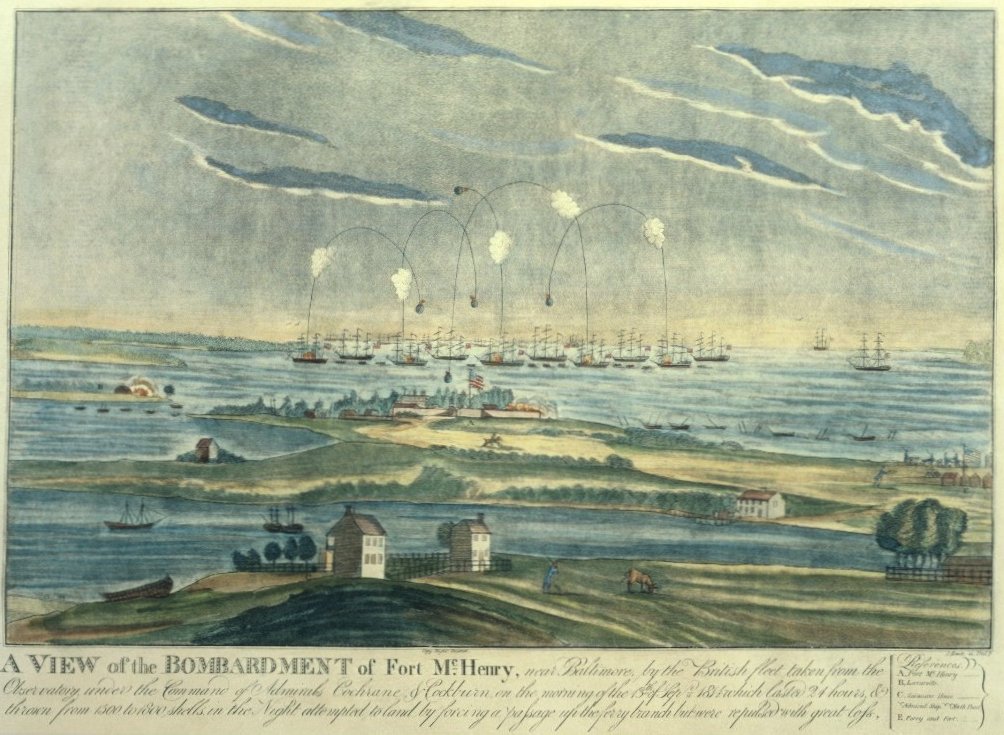

The caption reads “A VIEW of the BOMBARDMENT of Fort McHenry, near Baltimore, by the British fleet taken from the Observatory under the Command of Admirals Cochrane & Cockburn on the morning of the 13th of Sept 1814 which lasted 24 hours & thrown from 1500 to 1800 shells in the Night attempted to land by forcing a passage up the ferry branch but were repulsed with great loss.”

Although an attack on Baltimore had been under discussion

since the beginning of Vice Admiral Sir Alexander Cochrane’s Chesapeake Bay

campaign (April–September 1814), Cochrane waited for nearly two weeks after the

burning of Washington (24–25 August) before committing to the expedition.

The British were unaware that their reception at Baltimore

would differ greatly from what they had seen at their capture and occupation of

Hampton, Virginia (25–26 June 1813); at Washington; or at Alexandria, Virginia,

during Captain James Gordon’s raid on the Potomac River (17 August–6 September

1814). From the spring of 1813, Major General Samuel Smith of the Maryland

Militia had been in command of preparations with the full support of the city,

state, and federal governments.

The city lay at the base of the harbor, which was on the

Northwest Branch of the Patapsco. The entrance to this narrow inlet was blocked

by a boom, sunken hulks, and up to 11 barges (two guns each) of Captain Joshua

Barney’s flotilla with about 350 USN personnel. On the west point of the

entrance stood Fort McHenry, which held 36 French 42-pdr long guns (lg) and a

garrison of nearly 1,000 men (Corps of Artillery; Twelfth, Thirty-sixth, and

Thirty-eighth U.S. Regiments of Infantry; Maryland Militia; and some Sea

Fencibles) under Lieutenant Colonel George Armistead, while to the east was the

Lazaretto Battery with three guns manned by men from Barney’s flotilla. To

prevent a landing west of Fort McHenry via the Ferry Branch (the south branch

of the river), there was Fort Babcock (six 18-pdr lg), Fort Covington (up to 10

heavy guns), and Fort Lookout (seven guns) and one more small battery. The

first three were held by seamen from Barney’s flotilla and the USS Guerriere,

and some Virginia Militia held the fourth. Just before the arrival of the

British, the command of this part of the city, except for the naval parties,

was given to Brigadier General William Winder, who was greatly dissatisfied

with having to serve under Smith; Commodore John Rodgers commanded all naval

detachments.

In the days immediately before the British arrived, a

massive military and civilian force (including a proportion of slave labor) had

fortified Hempstead Hill on the city’s east side. This consisted of nearly a

mile and a half of trenches on the ridge joining eight batteries, which held 62

guns. These were manned by seamen and U.S. Marines from the Guerriere and a

regiment of Maryland Militia artillery. Infantry support came from elements of

two brigades of Maryland Militia, a battalion of Pennsylvania Militia, and some

U.S. Marines. Tentative plans had even been made to fortify buildings in the

city if necessary.

General Smith used Baltimore’s “City Brigade,” the Third

Maryland Brigade (about 3,200 men in five regiments of infantry and smaller

units of cavalry, rifles, and artillery), as his advance. On 11 September,

Brigadier General John Stricker, its commander, took up a position about four

miles east of Hempstead Hill at a narrow point on Patapsco Neck. He placed his

infantry here and sent part of his cavalry and rifles forward to watch the

British.

After arriving at the Patapsco River on 10 September with a

fleet of about 50 warships, the British began landing about 4:00 A.M. on 12

September at North Point, near the tip of Patapsco Neck. Led by Major General

Robert Ross, with Rear Admiral George Cockburn in attendance, the 1/85th

Regiment of Foot and the light companies of the 1/4th, 1/21st, and 1/44th

Regiments of Foot followed in time by the rest of these latter units and detachments

of the Royal Regiment of Artillery and the Royal Sappers and Miners; they

totaled about 2,500 men. About 1,350 men also landed from the 2nd and 3rd

Battalions of Royal Marines, the Royal Marine Artillery (and presumably men of

the Rocket Corps and the Rocket Troop) and RN officers and seamen. To provide a

diversion to the land force, Cochrane sent some of the smaller warships up the

river toward Baltimore.

While the landing was still under way, Ross advanced

westward with the light infantry around 8:00 A.M., covering about four miles

before halting; the heat and humidity were oppressive and took its toll on the

troops. About 10:00, the column advanced, and shortly thereafter the opposing

light infantry began skirmishing. About 2:00 P.M., with a guard of about 50

men, Ross and Cockburn rode up to inspect the action, and Ross was hit by a

rifle bullet and soon died. Command now devolved on Colonel Arthur Brooke (44th

Foot), who hurried to the scene and pushed the column forward where it engaged

more infantry and artillery sent forward by Stricker.

Stricker succeeded in enticing the British to his position.

With one of his units in reserve, he formed a line of his entire force behind a

fence just inside Godley Wood, spanning the width of Patapsco Neck. Before them

lay an old field about 500 yards wide, and here Brooke arrived and deployed his

skirmishers and main line under American artillery fire, which he returned with

guns and rockets. Brooke sent the 4th Foot to flank Stricker’s left, for which

Stricker made adjustments. With part of the remaining units in line and some

behind, waiting to deploy as they reached the field, Brooke ordered a slow

advance about 3:50.

Stricker’s left had difficulty deploying, and under their

first fire a portion of the units broke and ran. The rest of the line delivered

volleys and independent fire, but Brooke ordered a quickened advance, and as

the British rushed forward, Stricker’s line withered and broke. Brooke declared

that the action, which became known as the battle of North Point (or the battle

of Godley Wood among some authorities), lasted about 15 minutes. Some of the

British referred to it as a second “Bladensburg Races.” It had been a bloody

affair, however; the British reported 38 dead, 251 wounded, and 50 missing,

while Stricker claimed 24 dead, 139 wounded, and 50 captured.

Stricker was able to congregate his units and withdraw

toward Hampstead Hill, where Smith positioned him to the left, and outside, of

the fortifications; Smith also ordered Winder to this place with part of his

brigade of regulars and militia. Brooke camped on the battlefield, where his

men suffered without cover during a night of rain.

On 13 September, Brooke advanced and came within sight of

Hampstead Hill around 11:00 A.M. He was surprised at the strength of the

American position and soon heard rumors that 20,000 men stood ready to repel

him.

Meanwhile, the famous naval bombardment of Fort McHenry had

begun that morning around 8:00. Sixteen of Cochrane’s shallower draft warships

were within five miles of the city by late on 12 September. By the next

morning, five bomb vessels and the rocket ship Erebus moved to within two miles

of Fort McHenry and opened fire. The Americans returned this, and Cochrane

pulled his vessels back just out of range and resumed a tremendous bombardment

with mortars, guns, and rockets that lasted until early the next morning. It is

said the British fired between 1,500 and 1,800 rounds of mortars alone and that

400 of them fell on Fort McHenry, although surprisingly few casualties were

reported. It was during this remarkably explosive display that Francis Scott

Key formed the idea for his famous “Star Spangled Banner.” Around 3:00 A.M. on

14 September, Cochrane ordered a 1,200-man boat assault on the shore west of McHenry,

but this never made shore because of the fire of the auxiliary forts.

While the bombardment was going on, Brooke was retreating.

Cochrane had sent Cockburn a note questioning the value of attacking Hampstead

Hill. Cockburn showed it to Brooke, who called a council of war from which

Cockburn excused himself, not wanting, presumably, to “encourage” Brooke into

action as it was suggested he had done with Ross during the march to

Washington. After exchanging prisoners and wounded with the Americans, the British

marched back to North Point and were all embarked by mid-afternoon on 15

September.

The defense of Baltimore was unprecedented. It reestablished

American confidence and was used as a bargaining chip in peace negotiations.

The attack was a black eye for Cochrane and the military, although Brooke’s

decision to withdraw in the face of such formidable fortifications was probably

the right one.

THE CAMPAIGNS OF 1814 AND 1815

The new year of 1814 dawned with a fresh possibility for an

end to the war. After refusing to allow Russia to mediate matters, the British

offered to begin direct negotiations late in 1813, and in January, Madison

nominated Henry Clay and Jonathan Russell to form a five-man commission with

Adams, Bayard, and Gallatin at Gothenburg, Sweden; they arrived there in April.

Little action was taken in Washington during the winter to

plan new campaigns. Recruitment continued in new and old regiments, and there

were some changes made in their organization. Armstrong ordered Wilkinson to

break up his camp at French Mills, sending part of it to Sackets Harbor under

now–Major General Jacob Brown of the U.S. Army and the rest to Plattsburgh.

From there, Wilkinson made a halfhearted attempt to invade LC in March, but

this came to grief in a battle at La-colle, LC, on 30 March. By that time,

Armstrong had already recalled the erratic general to face an inquiry into his

St. Lawrence River campaign; Major General George Izard was given command of

the Right Division of the northern army at Plattsburgh, while Brown commanded

the Left Division. Secretary Jones gave Chauncey permission to construct four

new ships at Sackets Harbor and allowed Macdonough to build a warship and

gunboats at Vergennes, Vermont. Jones also divided Chauncey’s command by putting

Captain Arthur Sinclair in charge of Perry’s former squadron at Erie.

The British were building two frigates and a 100-gun ship at

Kingston and debating plans for regaining control of the upper lakes. Drummond

and Yeo proposed an ambitious attack on Sackets, but Prevost vetoed this,

making it known that he was expecting an armistice to be called shortly.

Nothing of the kind was to happen because, on 6 April,

Napoleon abdicated his authority, bringing an end (temporarily) to the great

European struggle. The British government now resolved to send some of its best

regiments and officers to America to settle the matter with force; these

numbers were added to reinforcements already on their way, eventually raising

British military strength to nearly 50,000 on all fronts.

Meanwhile, Drummond and Yeo modified their plans and

launched, on 5–6 May, an amphibious attack on Oswego, Chauncey’s key

transshipment point for heavy materiel sent from New York City. At the cost of

heavy casualties, the assault netted some guns, ammunition, rigging, and

stores, and Yeo followed it up by blockading the Lake Ontario shore between

Oswego and Sackets. Chauncey’s building had started late and an early thaw left

his supply trains bogged down in mud across New York, so the assault and

blockade worsened his dilemma. However, on 30 May, a small number of naval,

military, and native personnel guarding a supply convoy of bateaux headed from

Oswego lured nearly 200 seamen and marines from Yeo’s squadron into an ambush,

and captured or killed them all. Yeo soon lifted his blockade and returned to

Kingston with his larger ships after deploying four of his small vessels to

supply Drummond’s army on the Niagara Peninsula.

The Americans had started a campaign on the peninsula almost

by accident. Madison’s cabinet did not set its campaign goals until the first

week of June, and by that time Armstrong had sent Brown conflicting orders

until the general ended up at Buffalo preparing for an invasion of UC. This

scheme was pared down when the cabinet committed Sinclair’s squadron and a

military contingent for an expedition on the upper lakes instead of to support

Brown. “To give immediate occupation to your troops,” Armstrong suggested to

Brown, instead, why not capture Fort Erie?

Chippewa, Upper Canada, 5 July 1814. The British commander watched the advancing American line contemptuously, for its men wore the rough gray coats issued those untrained levies he had easily whipped before. As the ranks advanced steadily through murderous grapeshot he realized his mistake: “Those are regulars, by God!” It was Winfield Scott’s brigade of infantry, drilled through the previous winter into a crack outfit. It drove the British from the battlefield; better still, after two years of seemingly endless failures, it renewed the American soldier’s faith in himself.

Brown’s army, numbering about 5,000 men in the early phase,

captured Fort Erie on 3 July and then beat the British army under Major General

Phineas Riall at Chippawa on 5 July; Brigadier General Winfield Scott’s brigade

played a key role in this unprecedented American victory. Brown then advanced

to the vicinity of Fort George, where, he had been led to believe, Chauncey would

arrive with siege weapons and support. Chauncey’s squadron did not sail until

late in the month, and Brown ended up withdrawing to Chippawa and then engaging

Drummond in the bloody battle of Lundy’s Lane on 25 July.

The Americans withdrew to Fort Erie, which they enlarged and

improved, and Drummond soon followed to lay a siege. This period saw the most

intense fighting of the war on the Niagara Peninsula with the failed assault on

the fort on 15 August followed by weeks of skirmishing and sniping and culminating

in the face-to-face combat in a rainstorm during Brown’s sortie on 17

September. Drummond was lifting his siege at this point and fell back to

Chippawa, where Izard soon arrived, having been sent with his division from

Plattsburgh by Armstrong. Apart from a skirmish at Cook’s Mills, Izard

accomplished no more than Brown could, and when he retreated to Buffalo after

blowing up Fort Erie on 5 November, the last shots had been fired in anger on

the shores of the Niagara.

Had Madison’s cabinet kept its first intentions, Sinclair

would have transported Brown’s army to the Grand River, where the army would

have gone overland to attack the British at Burlington Heights. But

Michilimackinac continued to distract Madison and his advisers even though their

victory at Moraviantown had broken the back of Tecumseh’s native resistance so

that only a few of the “Western Indians” remained with the British, while many

of their people had gone home and would sign a treaty with Harrison in July.

Probably more interested in securing the fur trade than

native alliances, the administration sent Sinclair with 750 regulars and

militia volunteers to recapture the fur fort and destroy an RN dockyard rumored

to be under development in Georgian Bay. After numerous delays, the force

entered Lake Huron on 14 July, burned the abandoned British posts at St. Joseph

Island and at St. Mary, destroyed one merchantman and captured another, and

arrived off Michilimackinac on 26 July. The attack was made on 4 August and

ended in failure. Sinclair sent some of his vessels back to Lake Erie with

casualties and proceeded into Georgian Bay, but there was no dockyard to be

found. He had to content himself with destroying another merchantman before

heading for home, after leaving two schooners to intercept the British supply

route to Michilimackinac. Soon after his return to Erie, Sinclair was dismayed

to hear that a small band of RN seamen, infantry, natives, and traders had

captured both his schooners, giving the British a stronger upper hand on Lake

Huron and beyond.

While Sinclair pursued his mission, the American army on the

Detroit River made no effort to establish an American presence throughout

southwestern UC other then deploying several raiding parties into the Thames

River valley. These resulted in minor actions with British militia and

regulars, such as the skirmish at McCrea’s Farm (15 December 1813) and the

violent clash at the Longwoods (4 March 1814). Brigadier General Duncan

McArthur began a raid near the end of October with 1,000 men in support of

Brown’s army on the Niagara Peninsula, but he got no further than the

rain-swollen Grand River, burned some barns and homes, and routed the local

militia at Malcolm’s Mills (6 November 1814) before returning to Detroit. The

British did not try to reclaim this territory, choosing instead to patrol the

area and keep a reserve at Burlington.

For the first time since the Fort Dearborn massacre in

August 1812, action occurred west of the lakes. At St. Louis, Governor William

Clark of Missouri Territory (Meriwether Lewis’s partner in exploration) feared

a British invasion down the Mississippi from their fur-trade post at Prairie du

Chien in modern-day Wisconsin. In a preemptive strike, Clark captured the

village on 2 June 1814 with a company each of militia and regulars. He left a

detachment behind to build Fort Shelby and returned to St. Louis. News of the

occupation reached Lieutenant Colonel Robert McDouall at Michilimackinac, and

he quickly sent a force of regulars, fur traders, and natives to retake the

place, which they accomplished after a brief siege (17–20 July). The next day,

a relief force from St. Louis was attacked by Fox, Kickapoo, and Sac warriors

at the Rock Island rapids 100 miles south of Prairie du Chien. This prompted

Clark to send a second relief force, but it came to grief at the same place on

5 September. The village and the renamed Fort McKay remained in British hands.

The eastern flank of the northern border saw its major

action in 1814. Having launched and fitted out his new warship by early May,

Commander Pring attempted to interrupt Macdonough’s shipbuilding at Vergennes,

Vermont, but was repelled in the skirmish at Otter Creek (14 May). The

Americans sailed two weeks later with a stronger squadron, forcing Pring to withdraw

to Isle-aux-Noix. There was skirmishing along the border through the spring and

summer, but General Izard did not use his division to invade Canada. Instead,

Armstrong sent him in August to join Brown, leaving Brigadier General Alexander

Macomb in charge of about 3,500 regulars (many of whom were ill) at

Plattsburgh.

The regiments from Europe began arriving at Quebec early in

the summer, and with them came orders for Prevost to make an incursion into the

United States in coordination with other operations in Maine and Chesapeake

Bay. To this end, he formed an 8,100-man army in three infantry brigades, plus

dragoons, artillery, and natives. Prevost’s intention was to capture

Plattsburgh and, perhaps, advance farther south, but his scheme rested on the

RN squadron at Isle-aux-Noix defeating Macdonough. This was impractical since

the vessels were not fitted out fully, especially the newly launched frigate

Confiance, and were manned mainly with soldiers. Prevost arrived at Plattsburgh

on 6 September and impatiently called for the navy to join him. Under Captain

George Downie, the squadron sailed before it was properly prepared and suffered

an ignominious defeat at Macdonough’s hands on 11 September. Prevost had just

started his land attack (later than planned) when he heard of Downie’s defeat

and promptly called off the attack. The next day, the army returned to LC,

where Prevost was roundly criticized and eventually summoned home to face

charges brought against him by Commodore Yeo, who claimed he had goaded Downie

into action. The American victory was complete, and Macdonough and Macomb

became heroes.

Nearly 300 miles due east, the British had enjoyed much

greater success after a nearly bloodless campaign to occupy the easternmost

portion of Maine. Because the boundary between the territory and Canada had

long been disputed, the British government ordered Lieutenant General Sir John

Sherbrooke to seize the territory from the Penobscot River to New Brunswick as

part of its escalation of the war. With one regiment and several warships, the

British captured Eastport, Maine, on 11 July without a fight. In September,

Sherbrooke was at the head of four regiments in a large squadron that captured

Castine on the Penobscot River on 1 September and took Hampden and Bangor two

days later. Very little fighting occurred, and because of some judicious

administration, the subsequent occupation of the area (which lasted until April

1815) was conducted in an amicable way. Although swords rattled in Boston and

plans were discussed in Washington, no effort was made to regain the captured

territory.

The administration was too busy anyway with more immediate

problems at Washington. The plans discussed by Vice Admiral Sir Alexander

Cochrane and the British government before he left England were wide ranging,

and he had latitude to choose specific campaign goals. After taking command of

the North America Station at Bermuda in April 1814, Cochrane assessed the

situation and decided to center on the Chesapeake Bay region first. To that

end, he sent Rear Admiral Cockburn to establish a base at Tangier Island and

begin raids while he waited for regiments to arrive from Europe.

Cockburn resumed his aggressive activities, which included

stopping the advance of a gunboat flotilla under Captain Joshua Barney, USN,

and trapping it in the Patuxent River. When Cochrane finally arrived in August

with Major General Robert Ross and an army of 4,500, Cockburn recommended an

expedition up the Patuxent toward Washington. This led to the British victory

at Bladensburg (24 August) and the brief occupation and burning of Washington

over the next day. As a diversion, Captain James Gordon sailed a squadron up

the Potomac River to Alexandria, which surrendered without a fight. Despite the

effort of naval heroes John Rodgers, David Porter, and Oliver Perry to stop

Gordon with fireships and shore batteries, he soon rejoined Cochrane’s fleet.

These events humiliated the administration and threw it into

chaos. Armstrong was forced to resign, and James Monroe took his place as

secretary of war. After hesitating, Cochrane decided to attack Baltimore, but

Major General Samuel Smith of the Maryland Militia commanded there and had

greatly improved its defenses. Cochrane landed Ross early on 12 September to

attack the city’s flank, but the general was killed by a sniper a few hours

later. Smith’s advance force broke at the battle of North Point that afternoon,

but the extent of the fortifications and the determined resistance maintained

during the bombardment of the harbor and Fort McHenry on 13–14 September

convinced Cochrane to withdraw. The successful defense of Baltimore nearly made

up for the destruction of Washington.

Cochrane left a small force to blockade and raid the

Chesapeake and turned his attention toward the Gulf coast. In the spring, he

had sent naval and Royal Marine officers to form an alliance with the Creek

nation in preparation for an attack on New Orleans. The events of the Creek War

(1813–1814) and the competence of Brigadier General Andrew Jackson depleted the

strength of the Creek “Red Sticks,” and by September they could offer the

British little assistance. Not fully aware of this situation, Cochrane proceeded

with a plan that dedicated an army of 10,000 to the campaign.

Cochrane reached the staging point at Jamaica in November

and hurried on to the British base in western Florida, where he learned that

the Americans controlled Mobile, blocking the overland route to New Orleans. As

a result, he and Major General John Keane decided to approach the city by water

from the east, resulting in a slow and fatiguing transfer of men from ships to

shore. After a small USN flotilla made a brave but unsuccessful stand at the

battle of Lake Borgne (14 December), the British pushed on and gained their

beachhead at the Villeré plantation below New Orleans on 23 December.

Jackson had effectively coordinated the defense of New

Orleans and ordered an attack on the British the night they arrived. He failed

to push them off but set the pattern for what was to come. Even when Major

General Sir Edward Packenham arrived with most of the rest of the army, he was

not able to penetrate Jackson’s defenses, as he learned in actions on 28

December and 1 January 1815. His grand assault on 8 January quickly turned into

the sharpest British defeat of the war, with nearly 2,000 men killed, wounded,

and captured. Packenham and his second in command died of their wounds, and his

successor, Major General John Lambert, and Cochrane decided to pull out.

Jackson held his lines firm, expecting another attack. His brilliant

generalship made him the foremost hero of the age.

Lambert and Cochrane landed their troops on Dauphine Island

off Mobile to recuperate and then captured nearby Fort Bowyer on 12 February.

They might have been contemplating another attempt on New Orleans, but the

matter was soon nullified when news of peace arrived.

Cochrane had sent Cockburn to Cumberland Island on the border

of Georgia and Florida to begin a campaign that would potentially unite with

his own, but this did not get under way until January 1815, and it accomplished

little until halted in February.

Cochrane had extended the blockade to the entire American

coast, though the deployment of much of his force for the various campaigns

limited the blockade’s overall success. Still, merchants in both nations

complained loudly about lost capital (especially at the hands of privateers)

and gradually pushed their governments toward peace.

On the oceans, the opposing navies fought to a near draw in

1814 and the last ship-to-ship actions in 1815, with six victories for the RN

and seven for the USN. The British ended the cruise of the Essex at Valparaiso,

Chile, on 28 March 1814 and captured the USS President off New York on 15

January 1815. The smaller American cruisers, however, continued to show their

advantages over RN sloops sent to catch them, and the USS Constitution capped

its fighting record with the capture of two warships off Madeira on 20

February.

After innumerable delays, peace negotiations had finally

started on 8 August 1814 at Ghent in Dutch Flanders. They dragged on for four

months as the opposing commissions presented proposals and counterproposals on

wide-ranging topics. News of the burning of Washington set the American cause

back, but reports of the successful defense of Baltimore and Prevost’s failure

at Plattsburgh gave them an advantage. The British representatives had to refer

every item to officials in London, while the American delegates argued among

themselves. In the end, the British government decided to get out of the war,

fearing that the uneasy peace in Europe following Napoleon’s abdication was

about to collapse. On 24 December, the delegates signed the Treaty of Ghent,

which essentially ordered a return to a status quo ante bellum.