American forces in the Pacific and Asia did not have the

advantage of an ally like the British with extensive experience and advanced

equipment to carry the night defense load until US units were trained and

equipped for battle. The Japanese army and navy air forces dominated the day

skies in 1941 and 1942, however, and had no need to seek the night’s

protection. Only when the United States seized daylight air superiority after

January 1943 did Japanese night missions become the rule. To cope with this

growing problem, until the specially trained night fighter squadrons were

ready, the AAF redesignated the Hawaii-based 6th Pursuit Squadron a night

fighter unit. While the core of the unit remained in Hawaii to defend US

installations, in February 1943 one detachment deployed to Port Moresby, New

Guinea, and another to Guadalcanal with six P-70s each to help ground forces

struggling to defend those areas against enemy attacks. The crew members of

these units had no formal night training.

Equipped with SCR–540 airborne radar (equivalent to the

British Mark IV) and lacking superchargers, these first US night fighters

performed poorly. Most Japanese bombers flew above twenty thousand feet, while

P-70s struggled to reach that altitude and operated best under ten thousand

feet. Initially, the Americans lacked ground control radar, relying only on

vague reports of penetrating aircraft from coastwatchers. Crews had to develop

the techniques of ground controllers and antiaircraft artillery coordination in

combat. Against these obstacles, Pilot Capt. Earl C. Bennett and R/O TSgt.

Raymond P. Mooney of Detachment B on Guadalcanal claimed the first US

radar-directed (using the SCR–540, Mark IV airborne radar) night kill on April

19, 1943, though searchlights illuminated the enemy aircraft until radar

contact had been made. Pilot 1st Lt. Burnell W. Adams and R/O Flight Officer

Paul DiLabbio claimed the only kill for Detachment A at New Guinea in May.

Although three squadrons eventually flew P-70s in the Pacific theater, they

claimed only two victims. Eventually, the P-70s were withdrawn from night

combat altogether and used for attacks on shipping.

To make up for the technical shortcomings of the P-70, the

6th NFS acquired a few P-38 day fighters with the speed and altitude to

intercept enemy aircraft. Loitering at thirty thousand feet over Guadalcanal,

the P-38s had to wait for ground-based searchlights to illuminate enemy

bombers. This reliance on searchlights limited them to one night kill in May

1943. Later attempts to free the P-38s from this dependence by equipping them

with Navy AN/APS–4 airborne radars ultimately failed because of the excessive

workload imposed on the lone pilot.

The initial experience of the United States with night

fighters in the Pacific was not stellar. On March 20/21, 1943, Detachment B’s

P-70s failed to stop Japanese night bombers from damaging fifteen of the 307th

Bomb Group’s B–24s and five of the 5th Bomb Group’s B–17s on the ground at

Guadalcanal. Eight months later, in November, enemy night bombers sank one and

damaged three Allied ships at Bougainville. The AAF concluded from this initial

experiment in night fighting that “it proved impossible to prevent the Japanese

from inflicting some damage” on US ground and surface forces. In November 1943,

the AAF ordered the newly formed 419th NFS to Guadalcanal to rectify the

situation. Equipped with ground control radar, but lacking aircraft, the 419th

absorbed Detachment B of the 6th NFS. Demoralized by flying worn-out aircraft,

the new squadron flew only three night patrols, six scrambles, four intruder

missions, and four daylight sorties by the end of the year, claiming no enemy

aircraft at a cost of five aircraft and four dead crewmen. It was hardly an

auspicious beginning for Pacific-based US night fighters.

The 419th NFS, like all US night fighter units sent to the

Pacific, suffered from the low priorities of the Pacific war. The ten night

fighter squadrons that fought there had to make do with obsolescent ground

radars, including the 3-meter SCR–270 and 1.5-meter SCR–527, as the Microwave

Early Warning radar did not appear in the Pacific theater until late in the

war. Even this vintage equipment was too few in number, as priority went to

European operations. Spare parts, difficult to find in Europe, proved

impossible to secure in the Pacific. Also, the terrain of Pacific battlefields

sometimes interfered with night fighter operations, allowing Japanese intruders

to sneak in, shielded by mountains and hills. Ground radars were both

susceptible to severe echoing from ground returns and easily jammed. Optimally,

they had to be located in a flat area at least one-half mile in

diameter—difficult to find on the Pacific islands. Erecting radars near the

shore provided some relief.

Inexperienced radar operators only made matters worse. In

January 1944, for example, the 418th NFS’s fighter controller scrambled a P-70

to intercept a bogey, which was in fact another P-70 already on patrol against

Japanese intruders. Ground control then vectored the patrolling P-70 to

intercept the one just launched. While orchestrating a merry chase, the

inexperienced controller directed both P-70s into a US antiaircraft artillery

zone, where they received heavy ground fire. Fortunately no one was hurt,

though important lessons were learned about proper airground control and

communication.

Many of the enemy sorties US night fighters had to defend

against most often were not coordinated raids, but individual attacks by

“Bed-Check Charlie”—a nickname given to all such single flights, which seemed

to come at the same time each night. More nuisance than threat, the attacks

nevertheless affected morale and had to be stopped. Many chroniclers of combat

in World War II write with near reverence for these solitary visitors, even

recording remorse when night defenses downed a “Bed-Check Charlie.”

The 418th NFS joined the 419th at Guadalcanal late in 1943,

and its experience was typical of all the early squadrons in the Pacific. Its

P-70s, unsuccessful in intercepting Japanese bombers over Guadalcanal, were

ordered to switch to night intruder work. From Guadalcanal, the 418th

accompanied MacArthur’s drive toward the Philippines and Japan, moving to

Dobodura, then to Cape Croisilles, Karkar, Finschhafen, and to Hollandia, New

Guinea. In May 1944 the squadron converted to B–25s, allowing it to carry more

ordnance on night intruder missions and have a better range for sea sweeps.

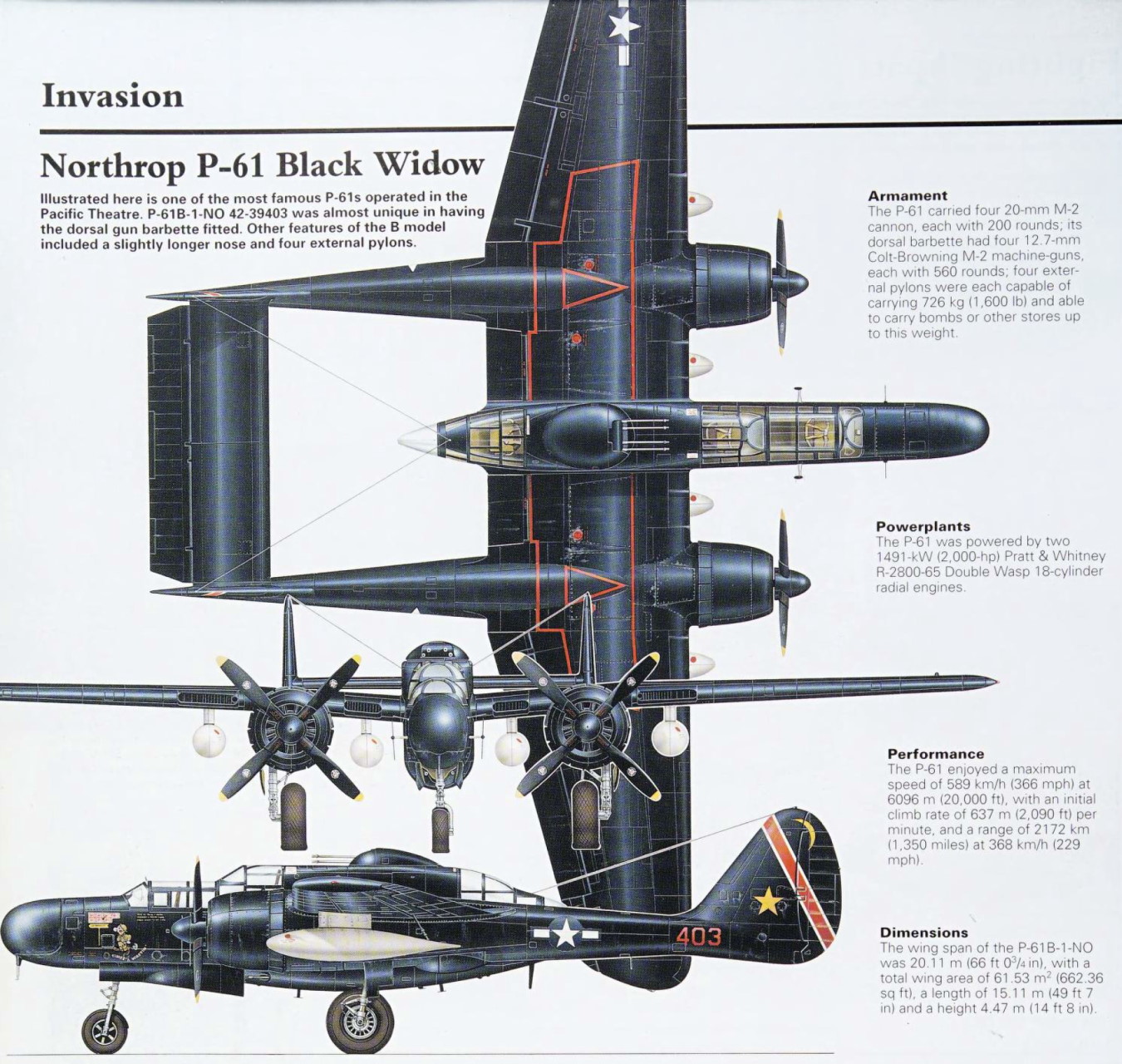

In August 1944 P-61s became available in the Pacific

theater, and the 418th, equipped with them, converted back to defensive

patrols, scoring four kills on Morotai and five from Mindoro during the Luzon

campaign. In the thirteen nights following December 27, 1944, the 418th gained

twelve of its eighteen victories of the war. Piloting a Black Widow, Maj.

Carroll C. Smith became the highest scoring night ace of the war, achieving

four kills on two missions on the night of December 29/30. Altogether, Smith racked

up eight kills, though three of them came during the day. His R/O for the five

night victories was 1st Lt. Philip B. Porter.

Meanwhile, the failure of B–24 night intruder missions over

Luzon forced the 418th NFS to postpone its night fighter operations and return

to night harassment and interdiction missions in support of MacArthur’s forces.

From the Philippines the unit went to Okinawa in July 1945, starting intruder

missions against Japanese airfields on the home island of Kyushu. Pilot 2d Lt.

Curtis R. Griffitts and R/O 2d Lt. Myron G. Bigler claimed the last night

fighter kill of the war during these operations.

At Wakde, the 421st NFS got its first kill on July 7, 1944,

after seven months of fruitless night patrols with P-70s and P-38s, and then

scored five more kills on Owi Island, four of them on the night of November 28

alone. It was on Owi that the “Mad Rabbiteers” of the 421st claimed the most

unusual night kill of the war. Pilot Lt. David T. Corts, hard on the tail of a

Japanese bomber, put his P-61 into a sharp turn when R/O Lt. Alexander Berg and

gunner SSgt. Millard Braxton warned him of an enemy fighter on their own tail.

Just as Corts pulled away, the fighter opened fire and shot down the enemy

bomber; Corts and his crew did not receive official credit for the kill.

Against aircraft that could reach their altitude, Japanese attackers resorted

to the heavy use of window/chaff, which proved generally ineffective against

the P-61’s SCR–720 radar. On some missions the enemy used fighters at low altitudes

to draw Black Widow patrols away from high-flying bombers.

According to the AAF, the “defense of Morotai [an island halfway

between New Guinea and the Philippines] was probably the most difficult task

undertaken by American night fighters during World War II.” Because of

MacArthur’s island-hopping strategy, Japanese air bases at Mindanao, Borneo,

Halmaheras, and the Palaus and Celebes Islands surrounded Morotai. Mountainous

terrain caused permanent echoes on early warning and ground control radars,

creating blind spots through which Japanese bombers could penetrate without

being detected. Sixty-three separate raids took place between October 8, 1944,

and January 11, 1945. The defenders had P-38s orbit over their airfields at

25,000 feet, while antiaircraft artillery with its shells fused at 20,000 feet

fired at the intruders. If searchlights illuminated a target, the ground fire

stopped while the P-38s pounced on the now-visible enemy. Meanwhile, the P-61s

of the 418th and 419th Squadrons orbited outside the ring of antiaircraft

artillery fire, waiting for orders from the ground control radar fighter

controller to vector them to a target. The defenders made sixty-one

interceptions with their airborne radar, claiming five kills.

At Leyte in the Philippines, US daylight air power proved so

deadly that enemy forces converted to night-time attacks almost immediately

after the invasion. The arrival of the 421st NFS on October 31, 1944, promised

to parry these blows, but the P-61 Black Widow lacked the speed advantage to

intercept fast high-altitude Japanese aircraft that used water-injection to

increase engine power. Crewmen of the 421st nevertheless proved what efficient

coordination between ground control radar and the P-61 could accomplish,

downing seven intruders before being relieved by Marine single-engine night

fighters. These seven kills included four on the night of November 28. Joined

by the 547th, the 421st spent the remainder of the war flying night convoy

cover, PT boat escort, and long-range intruder missions against the Japanese

home island of Kyushu. The thirteen kills of the 421st NFS and six of the 547th

stood in stark contrast to the last US night fighter squadron to arrive in the

Pacific, the 550th. It flew in combat for eight months with P-38s by day and

P-61s by night, without aerial success.

In 1944 Japanese night bombers launched a major effort to

disrupt the construction of US airfields on Saipan needed for the B–29 campaign

against the home islands. Flying P-61s, the 6th NFS began defensive operations

nine days after the Marines’ June 15 landing. Enemy attackers held the

initiative until new Microwave Early Warning radars linked to SCR–615 and

AN/TPS–10 “Li’l Abner” height-finder radars made three Japanese sorties one-way

trips. In thirty-seven attempts at interception from June 24 to July 21, the

defense made twenty-seven airborne radar contacts and claimed three kills. It

was on Saipan that a Pacific-based P-61 Black Widow snared its first victim on

June 30, 1944.

A typical Japanese aerial assault force consisted of a dozen

Mitsubishi G4M Betty bombers flying twenty miles apart. P-61 crews discovered

that if they could shoot down the lead bomber, the others would jettison their

bombs and flee. Black Widows from the 6th NFS and the 548th NFS downed five

additional enemy intruders before the attacks stopped in January 1945.

Thereafter, boredom set in for the crews of the 6th defending Saipan.

Occasionally success alleviated the boredom. Ground control

radar vectored the 6th Squadron’s “Bluegrass 56” over Saipan for five minutes,

until R/O Flight Officer Raymond P. Mooney picked up the bogey on his airborne

radar. He reported that

the Bogey was traveling very slowly and after closing to

400 feet our craft held position for 3 minutes and finally got visual contact.

Bogey was a Japanese single-engine dive-bomber (Kate). 90 rounds of 20-mm was

fired point blank into the enemy plane. The fire was plainly seen to enter the

right wing and fuselage. By accident cockpit lights flashed on in our craft

blinding pilot and preventing further observation.

The fighter controller notified Pilot 2d Lt. Jerome M.

Hansen that the bogey had disappeared from the ground control radar scope just

as Hansen had reported opening fire. The kill had to be listed as a probable,

though Hansen and Mooney received the Air Medal for their efforts. Mooney was

the 6th’s lone ace, with five kills to his credit.

The fighter controller notified Pilot 2d Lt. Jerome M.

Hansen that the bogey had disappeared from the ground control radar scope just

as Hansen had reported opening fire. The kill had to be listed as a probable,

though Hansen and Mooney received the Air Medal for their efforts. Mooney was

the 6th’s lone ace, with five kills to his credit. his second pass, the ground

controller reported the bogey was friendly The overeager P-61 crew from Saipan

had already put six large holes in the US Navy PBM patrol aircraft, a near

tragedy. The PBM had to be beached after landing to prevent it from sinking.

Though uttering a few choice, but not repeatable phrases, the Navy reported no

injuries. The rules of visual engagement were perfectly clear; unfortunately,

the humans who executed them were not perfect.

Saipan was also the site of the United States’ first effort

at airborne warning and control. Two B–24s of the 27th Bombardment Group

equipped with radar sets were to vector P-38s to intercept Japanese aircraft.

Unfortunately, the system was never used in combat.

On Iwo Jima the AAF combined the SCR–527 and SCR–270 radars

for early warning acquisition and the AN/APS–10 for ground control of

interception operations to stop the two or three Japanese bombers attacking

Allied forces on this island each night. Early warning radar would detect the

bombers’ presence at around 140 miles, between seven thousand and fifteen

thousand feet high. At fifty-seven miles, the “Li’l Abner” ground control would

make contact and begin vectoring defending P-61s of the 548th and 549th to

intercept them. Usually, the Japanese intruders would drop window/chaff at

thirty miles, blocking the older metric early warning radars, but the microwave

3-centimeter AN/TPS–10 kept working. Within ten miles of the Iwo ground radar,

the night fighters would break contact, and antiaircraft artillery would take

over. Eventually, after May 1945, there were few intruders to attack, and the

two night fighter squadrons soon shifted focus to intruder work in the Bonin

Islands.

Night intruder work to cut off Japanese garrisons on

scattered islands proved critical in the Pacific war. Generally this involved

attacks on enemy shipping. Because P-70s were ineffective in the night

interception role, commanders pressed them into intrusion work as early as

October 1943. When P-61 night interceptors began arriving in the early summer

of 1944, night intrusion work stopped until the spring of 1945. Soon, Allied

victories left few Japanese bombers to attract night fighter attention, and US

night crews returned to intruder operations.

Preparing for the invasion of Bougainville, Detachment B of

the 6th NFS from Guadalcanal began bombing Japanese airfields there in October

1943. Squadrons such as the 418th switched from P-70s to B–25s to improve the

efficiency of their night intruder missions. Bigger bombers meant bigger bomb

loads and longer range. For its part, the 418th NFS developed an innovative way

of attacking enemy positions in cooperation with PT boats patrolling near

Japanese-held islands. As guns onshore opened fire on the decoy boats, the

B–25s attacked the muzzle flashes so visible at night. Commanders also used

night fighters to suppress night artillery, a job reportedly much appreciated

by Marine and Army units struggling against stubborn Japanese defenders.

Night flyers quickly found that skip-bombing attacks on

enemy shipping, so effective by day, were also possible at night. Without

radar, airmen had trouble seeing ships at night, but soon discovered their

wakes were a dead giveaway. Flying at 250 feet, fighters and bombers, including

B–17s and –24s, dropped their bombs about sixty to one hundred feet short of

the target, allowing the bombs to skip into the side of the targeted vessel.

Some four-engine B–24 bombers were equipped with SCR–717 air-to-surface radars

for finding targets at night and AN/APQ–5 low altitude radars for bomb aiming.

Called “Snoopers,” three squadrons of about forty B–24s serving with Fifth,

Thirteenth, and Fourteenth Air Forces claimed to have sunk 344 enemy ships,

barges, and sampans at night, with 62 more probably destroyed and 446 damaged.

Missions in the China-Burma-India Theater

The P-61s of the 426th NFS went to China in November 1944 to

protect B–29 bases from Japanese intruders. As elsewhere, the night fighters

found the hunting poor, claiming only four kills by February 1945. Though

shifted to primarily night intruder work, P-61 crews also attacked enemy

personnel attending signal fires that guided Japanese night bombers to US

bases.

Within the CBI, the greatest success in night intruder work

occurred in Burma, largely because the Japanese were forced to use a single net

of north-south roads, one railroad, and the Irrawaddy River. Day fighters again

drove the enemy to operate mainly at night, creating attractive targets for the

P-61s of the 427th NFS and the B–25 Mitchells of the 12th Bombardment Group and

the 490th Bombardment Squadron. Flying at 1,500 feet, these aircraft followed

preassigned roads until they spotted truck lights. Diving to 150 feet, they

swept down the road with guns blazing. Standard procedure called for a return

twenty minutes later to restrafe burning vehicles and hamper the enemy’s

recovery efforts.