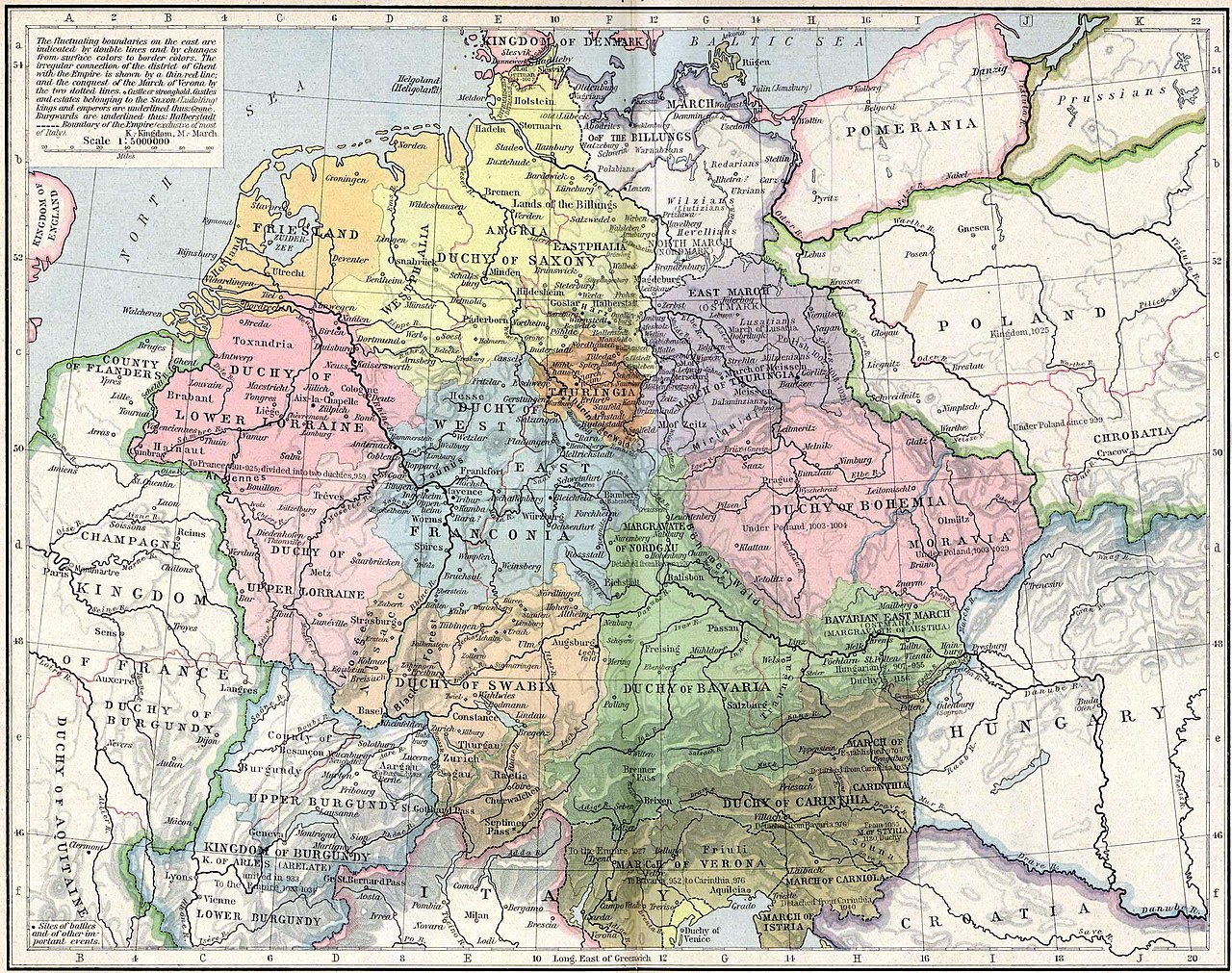

Central Europe, 919–1125. The Kingdom of Germany included the duchies of Saxony (yellow), Franconia (blue), Bavaria (green), Swabia (orange) and Lorraine (pink left). Various dukes rebelled against Otto’s rule in 937 and again in 939.

It will have been seen that Otto’s cherished policy with

regard to the duchies had been a miserable failure. He had hoped to found a

patriarchal state, as it were, and to bring the highest temporal offices into

the hands of his own relatives. The result had been a civil war. Otto’s son,

Liudolf, and his son-in-law, Conrad, had allowed no ties of blood or of

marriage to stand in their way. The people of the duchies, too, had, in more

than one case, shown their impatience under the yoke of dukes foreign to their

stem.

Otto now gave up the plan of uniting local interests through

a network of family ties. On his brother Henry’s death, in 955, he gave Bavaria

to a grandson of the old Duke Arnulf. Hermann Billung was made duke of Eastern

Saxony, and native nobles held office in Swabia and Lorraine.

It was, however, almost necessary to the existence of the

crown that it should be supported by a strong party, and Otto was led into a

step which, however advantageous at first, was fraught with dire consequences

for the German people. He made the Church that which the duchies should have

been, the prop and stay of the kingly power. He encouraged new ecclesiastical

foundations, and made rich gifts of lands and exemptions to the clergy, hoping

in this way to bind them more closely to himself. His first care was to fill

all the archbishoprics with friends and faithful servants.

William, Otto’s own bastard son, received Mayence, Bruno was

established in Cologne, and a pupil of his in Treves. For more than a century

now the history of the German Church and of the German kingdom were to become

almost identical. The government assumes a churchly character, church rule

becomes a matter of politics. The result was to be that when in the next

century the struggle with the popes began it was no longer possible for the

princely ecclesiastics to render unto Caesar that which was Caesar’s, and thus

to avoid the conflict of nationality versus the Church universal.

So long as the right of choosing the bishops remained with

the king, the latter was able to constitute a body of men whose interests were

identical with his own. The bishops were simply officials; they left no heirs,

being not allowed to marry, and at their deaths their sees reverted to the

crown. They made a splendid counterpoise to the power of the nobles, who were

already beginning to claim that their fiefs were hereditary. Estates, honours,

and riches could safely be given to such men, and the crown lands yet suffer no

diminution.

Great were the services demanded of the clergy in return. As

fief holders they furnished regularly their quota of vassals to the king’s

army, and often took the field in person. All the business of the court, all

the charter writing, all the correspondence, was in their hands.

And Otto ruled them like a second Charlemagne. No council

might be called, no decree of the clergy passed, without his consent. Of his

own accord he founded bishoprics, and set up bishops, judged the clergy, and

disposed of church funds. The canon laws indeed, and not only the forged ones,

directly negatived such proceedings, but as yet there was no one to call

attention to such discrepancies.

The immediate result of the union of the crown with the

clergy was to raise the prestige of Germany, and to pave the way for the

renewal of the holy Roman Empire. A time was to come, however, when the

interests that joined the two were to be sundered, and the bonds that bound

them loosed. The result was to be destructive indeed. The glory of the empire

was to be tarnished, and German unity to be trodden under foot.

For a hundred years now the crown of the empire had been a

mere bauble, the disposal of which had been for the most part in the hands of

the popes. Neither Charles the Bald nor Charles the Fat, Arnulf, nor Berengar

I., nor any of the other rulers of Italy seem to have regarded it as more than

an empty honour. Alberic, the ruler of Rome, had not cared for the title, and

had thwarted the plans of those who did. During his time, therefore — after wielding

the sceptre for twenty years, he had died in 954 — it remained in abeyance.

Alberic’s mantle, as head of Rome, descended upon his son

Octavian, a mere boy. Octavian, in spite of his youth, however, was soon made

Pope under the name of John XII., thus combining in his person the sovereignty

of Rome and the spiritual headship of Christendom. His great ambition was to

increase his temporal power in Italy, but in this he was thwarted by Otto’s old

enemy and vassal Berengar. At this time Berengar and his son Adalbert were in

possession of the Exarchate of Ravenna, and the dukes of Tuscany, to which the

pope also laid claim, did them homage.

Pope John looked around for allies, and, finally, fixed his

hopes on the German King. Otto had again broken with Berengar, and in 956 had

sent his son Liudolf to Italy, promising him the crown of that fair land if he

could win it. Liudolf within two years had subjected nearly the whole of the

so-called Italian kingdom — the present Tuscany and Lombardy. The “path was open

to Olympus,” as a monk of the time has expressed it, when the heir to the

German throne was attacked by fever and died. All the advantages won over

Berengar were lost, and the Pope once more trembled before him. He felt himself

insecure even in his own Eternal City.

It was then that John decided to summon Otto’s aid and to

dazzle him with the prospect of the imperial crown. Otto was won by the lure,

and the first steps were taken towards that union with Italy that was to cost

the nation so dear. Otto made hasty preparations for his expedition. His son

Otto was elected and crowned co-regent, Bruno was to uphold the royal rights in

Lorraine, and William of Mayence to transact the daily business of the realm.

In the autumn of 961, the king crossed the Brenner.

Berenger had raised an army of 60,000 men, but at the

decisive moment his troops refused obedience. Otto was able to enter Pavia

unmolested and to pursue his way to Rome. In February, 962, he received the

crown in St. Peter’s from the Pope’s hand.

It was not altogether without fear that Otto had entered

Rome. His sword-bearer had orders to watch while the king knelt before the

grave of the apostle, and to hold his weapon in readiness. The fickleness of

the Romans was well known to Otto, also, to some extent, the character of the

Pope. John was obliged to swear by the holy bones of St. Peter that he would

never make common cause with Otto’s enemies, Berengar and Adalbert.

The price to be paid to the Pope for Otto’s new dignity was

to be the provinces held by the two Italians. These were as yet unconquered,

but a deed of gift was drawn up concerning them which is still extant. Written

upon purple parchment in letters of gold, it has withstood the ravages of time.

Its genuineness, long doubted, has been re-vindicated in our own day.

The “Holy Roman Empire of the German Nation” as founded by

Otto the Great, was to continue for eight hundred and forty four years. Only

for short intervals was the throne ever to be vacant, although in the sixteenth

century the Pope’s influence in the matter of its disposal was to fall into

abeyance. In the time of our own grandfathers it came to an end, and the

Austrian Empire, the anomalous kingdoms of Napoleon, and the North German

Confederation rose on its ruins.

For two weeks after Otto’s coronation harmony lasted between

the heads of Christendom. The Pope approved of the emperor’s plan of changing

Madgeburg into an archbishopric with many suffragan bishoprics. The details of

the matter were arranged in a Roman synod and made known to the German clergy

by a papal bull. But John soon found that Otto was playing by far too important

a role in Italy, was winning over the bishops by rich donations, and was

treating the provinces that he conquered completely as his own.

The Pope did not hesitate to commence negotiations with

Berengar and Adalbert. The same messengers who brought news of this turn of

affairs had much to say about John’s ungodly manner of life. Otto was little

affected by either of these communications, and is said to have remarked with

regard to the charges of immorality: “He is a boy, the examples of good men

will improve him.”

But one day papal ambassadors were arrested at Capua with

letters to the Greek Emperor and to the Hungarians. John confessed his

treasonable intents in part, but made counter-charges against Otto which the

latter condescended to explain away. The crisis, however, was not long in

coming. Adalbert was received within the walls of Rome and warmly welcomed by

the Pope. Otto marched against the city, which he took without difficulty. The

Pope fled with Adalbert.

The Romans were made to give hostages and to swear never

again to install anyone as pope whose election should not have been confirmed

by the emperor and his son. Such an influence as this did Otto win over the

Roman Church! The popes became his creatures and he their judge.

A synod was summoned over which Otto presided. It was well

attended. Three archbishops and thirty-eight bishops came together in St. Peter’s.

All the clergy of Rome and the officials of the Lateran were present, also many

nobles and the Roman soldiery.

Otto refrained at first from bringing his own causes of

complaint before the synod. He wished John’s ruin, but the Pope’s daily manner

of living was enough to condemn him. A long list of sins was brought up against

him, and his contempt for the canons of the Church was clearly proven. He had

drunk the devil’s health, and had invoked heathen gods while playing dice. He

had chosen a ten year old boy as bishop of Todi and had given a deacon his

consecration in a horse’s stall. He had lived like a robber-chief, and an

impure and unchaste one at that.

The synod summoned John to answer the charges against him.

He replied by banning the bishops who had taken part in the proceedings. A second

summons was likewise disregarded.

At the third session of the synod Otto came forward as

accuser and declared the pope a perjured traitor, who had conspired with the

enemies of the empire. John’s deposition was agreed upon and a new pope

elected, but it was some months before the matter came to a settlement. John

had found adherents in the city, but died just as Otto was preparing to crush

him.

The Romans disregarded Otto’s pope, Leo, and elected the

cardinal deacon, Benedict. The result was a siege of Rome, famine in the city,

and a capitulation. Again a synod and again a triumph for the emperor. Benedict

appeared before the assembly and begged for mercy. Clad in the papal robes and

holding the bishop’s staff he had come to the synod. He left it stripped of his

pallium, his staff in pieces, himself a prisoner. He was to die in captivity at

Hamburg. The last hopes for the Romans of freeing the papacy had proved in

vain. One German after another now ascended the throne of Peter.

Otto’s last years were spent partly in administering the

affairs in his own land, partly in trying to preserve quiet and to increase his

power in Italy. On Margrave Gero’s death, in 966, in order that no one man

should again have such a preponderating influence in Saxony, his district was

divided into six parts with each a separate margrave. Lorraine, too, was

divided into an upper and a lower duchy, and these parts were not again to be

reunited.

Otto’s mere reappearance in Rome sufficed to quell an

insurrection against his pope. He then proceeded to fulfil the promise once

made to Pope John XII. All of its earlier possessions were restored to the

chair of Peter, although the imperial rights in the ceded districts seemed to

have been preserved. Otto, for instance, built a palace near Ravenna, where he

often held his court.

Otto now made an effort to reap lasting fruits from all of

his untiring labours. He wished to secure the empire to his son, to unite the

latter by bonds of marriage to the still influential court of Constantinople, and,

finally, to rid Italy of the Arabs who had been infesting it for a hundred

years. The last of these desires was not to be accomplished either in his own

or in his son’s reign. The consent to the imperial coronation was easily

obtained from an obsequious pope, and the ceremony took place in St. Peter’s on

Christmas day, 967.

The union with the Eastern Empire was only brought about

after endless negotiations and some bloodshed. Otto, determined to exert

pressure on the Greeks, invaded their possessions in Apulia and Calabria and

besieged Bari. He soon withdrew, however, and sent Bishop Luitprand of Cremona

at the head of a large embassy to Constantinople. Luitprand was a man of

letters and a skilful diplomat, but somewhat rash and fiery of temper. To him we

owe most of our knowledge of these times; and among his other works is a

detailed report, addressed to Otto, of his mission. It is one of the most

attractive writings of the middle ages.

Luitprand found Nicephorus one of the haughtiest and most

insolent of men, living in a style of great magnificence and utterly refusing

to believe that any power in the world could equal his own. He demanded Rome

and Ravenna as the price for the hand of a royal princess, and offered an

alliance without the marriage if Otto would make Rome free.

While Luitprand was detained at the court of Nicephorus,

Pope John XIII. sent an embassy to the “Greek emperor.” Only the low degree of

the envoys saved them from instant death, for Nicephorus considered himself the

emperor of the Romans, and the only one.

Luitprand’s mission was a failure. He met with insults and

taunts from the Greeks, and repaid them in kind. He was absent so long,

virtually a prisoner, that Otto renewed hostilities without awaiting his

return. But soon a revolution took place in Constantinople. At the instigation

of the empress Nicephorus was murdered, and John Zimisces succeeded to his bed

and to his throne. Zimisces, surrounded by enemies at home, was quite willing

to give the hand of a Grecian princess in return for peace in Italy. Theophano,

the niece of Zimisces, reached Rome in April, 972, and was wedded to Otto II.

in St. Peter’s. She was a gifted creature, and was destined to play a very great

part in German affairs.

A number of provinces and estates were settled on the young

bride, and the original of the deed of transfer, drawn up in purple and gold,

is extant to-day.

In 968 Otto’s favourite project of making Magdeburg an

archbishopric, a project which had met with some opposition in Germany itself,

was at last realized. The bishoprics of Brandenburg, Havelberg, and Meissen

were subordinated to the new creation, also two new sees, Zeiz and Merseburg,

to which, later, Posen was to be added. A grand centre for carrying on the

conversion of the Slavonians was at last won.

Otto’s life-work was nearly done. Few German emperors have

been able to end their days amid such general prosperity and rejoicing. He was

able to take part, in 973, in a series of feasts and processions in Saxony, but

died at Memleben before the year was out. He had reigned thirty-seven years,

and had reached the age of sixty-two. His bones rest in the cathedral of

Magdeburg.

It remains to say a few words about the social and intellectual

life in the reign of Otto the Great, and it must be membered in this connection

that different parts of Germany differed much from each other in the degree of

their culture and civilization. There was no general state organization in our

sense of the word, and the duchies enjoyed a great degree of independence. The

king might demand certain services of the dukes, but he could not interfere

with the administration of their duchies. Here they were absolute masters,

except when held in check by their local diets.

One such assembly in Saxony dared to oppose the wishes of

Otto himself, although, he represented king and duke in his own august person.

It is questionable whether at any time in the tenth century a royal or imperial

command which was contrary to a local law would have been obeyed. The people at

this time, as during the next two hundred years, were devotedly true to their

dukes. How easily could one of them raise an army for his own purposes, and how

many of the old German songs centre about the beloved person of a duke who, as

likely as not, had been a traitor to his king!

We must remember at every turn how different the people of a

thousand years ago were from ourselves. Cities as centres of trade and commerce

had scarcely as yet come into being, and the use of money was extremely

restricted. If taxes or tolls had to be paid they were paid in kind. This or

that proportion of grain or cloth was subtracted from the rest and reserved for

the treasury of the king. Even the produce of the rich estates belonging to the

crown was not sold. We know now why it was that the kings of the tenth century

moved so frequently with their huge followings from place to place. It was

necessary to consume the products of the soil, for they were perishable and not

convertible. A modern historian likens the royal household to a ruminating

animal that grazes up one pasture after another.

Family life, to turn to a special phase of social existence,

was a far different conception from what it is now. Among the Saxons, Thuringians,

and Frisians, marriage seems to have been purely a business transaction, which

was carried on independently of the wishes of at least one of the parties

concerned. Fathers could dispose of their daughters at will, and regularly sold

them to their future lords. The husband was master of his household in the strictest

sense of the word, and the women were kept in complete subjection. Conjugal

fidelity was a one-sided affair, and the marriage vows were binding only on the

wife. The father had a right — how much use he made of it we shall never know —

to kill his children or to sell them into captivity.

It is possible that religious considerations tempered the

brutality of the laws. We know that Otto the Great’s age was one of great

piety, not to say superstition. The king himself, especially after the death of

his first queen, Edith, which event was considered by him a warning to call him

to good works, was untiring in furthering missions. His mother had founded

several monasteries, and his daughter herself became abbess of Quedlinburg.

Otto’s brother Bruno, who was his chancellor and

archchaplain, instituted a far-reaching reform in the church affairs of

Lorraine. He summoned clergy of blameless life from all parts of Germany.

Monasteries which had sunk into decay were purged and regenerated. Old schools

were bettered and new ones founded. The Lorraine clergy were models for Europe

in education, as well as in the proper performance of their duties. Bishops

without number were chosen from their midst, and Rheims raised two men from

Lorraine in succession on her archiepiscopal throne. A century later Rome

herself was to choose a pope from this rich nursery of prelates.

The religious life of Otto the Great’s age was not without

its anomalies. A stiff formalism pervaded this as every other phase of

existence. Humility in those chosen to a high position in the Church consisted

in a routine of refusing to accept the dignity, of fleeing behind the altar, of

weeping copious tears, of self-deprecation. Not once but a hundred times do

such performances meet us in the chronicles, and one case is known of a regular

formula for the proper conduct on such occasions. Piety and charitable intent

were often measured by the power to shed tears less or more copiously.

The strange belief was almost universal that the end

justified the means. We read of housebreakings and robberies, of forgeries and

other crimes committed for the sake of obtaining the relics of this or that

saint, and in all the literature of the time we hear no disapproval of such

acts except from the side of the injured parties. On the contrary, biographers

frequently praise their heroes for just such performances.

An excessive saint worship and an extreme credulity went

hand in hand with such moral ideas. Miracles were thoroughly believed in, not

as now merely by the ignorant, but by the best intellects of the time. The more

a man could believe the higher was his piety reckoned.

In art and literature, Otto’s court was the scene of a

veritable renaissance. Countless miniatures or book illustrations of his time

are still preserved. In St. Grail, Treves, Regensburg, and elsewhere, were

famous schools for such ornamental work, and the colours used were most

brilliant and enduring. Strangely enough they were used without any sense for

the real fitness of things. Scarlet eagles fly through cherry clouds, yellow

asses pasture in blue fields, and red oxen draw golden ploughs. Towards the end

of the century the taste changed and more sombre hues crept in. It has been suggested

that ascetic views, such as those which were so diligently fostered by Otto

III., were responsible for the transformation.

Otto the Great, although personally, as far as we know,

without literary tastes, did everything to foster and encourage a revival of

classical learning. We hear of an Italian who at his instigation brought a

hundred manuscripts over the Alps. Virgil, Horace, Ovid, Terence, Cicero and

Sallust arose from the dead as it were to a new life in Germany. They found

their way into the monasteries and even into the nunneries.

Who has not heard of Roswitha, Abbess of Gandersheim, who

wrote comedies in the style of Terence, but with the outspoken object of

maintaining the field against him? Her aim was “that the praiseworthy chastity

of holy virgins should be celebrated in the same poetic strain in which

hitherto the loathsome incest of voluptuous women has been narrated.” Her works

have been published in our own day, and fill a respectable volume.