The Battle

Glaring silently at each other across the burning sands of a

lonely seaside plain near Raphia, two of the most powerful kings on earth,

Antiochos III and Ptolemy IV, each waited tensely for the other to make the

first move. The rival armies stood poised for action, separated by only a few

hundred yards of barren terrain as the withering afternoon sun beat down on

them.

In the Seleukid phalanx, frontline soldiers tipped back

their helmets and nervously shifted their sarissai from hand to hand as

officers paced back and forth, continually glancing off toward the far right,

where their young king was positioned with his royal guard. Across the field,

the common soldiers of the Ptolemaic phalanx waited impatiently in their

tightly-packed formation as drifting sand blew fitfully through their sweating

ranks. Then, in an instant, almost before either army knew what was happening,

the blast of a distant trumpet rang out and the great battle began.

Intending to crush Ptolemy with his strongest units before

the pharaoh’s superiority in heavy infantry could be brought to bear, the

impetuous Antiochos decided to stake his chances of victory on a risky

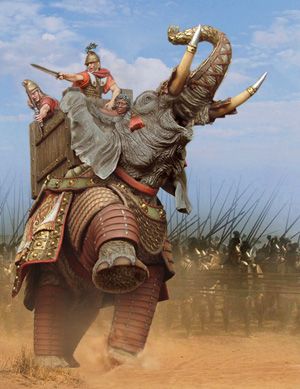

manoeuvre. On his command, the sixty war elephants guarding his right wing

surged powerfully toward the Ptolemaic line. Storming forward carrying towers

manned by phalangites and missile troops, the Seleukid beasts were a terrifying

sight to behold. From his position directly opposite this onslaught, Ptolemy

observed the great clouds of dust rising from the pounding feet of the

approaching enemy beasts and calmly ordered his response. In a matter of

seconds an answering charge of the pharaoh’s forty left-wing elephants pressed

forward. All across the battlefield, the eyes of soldiers and officers were

drawn toward the spectacle unfolding on the seaward flank as the opposing lines

of war elephants charged toward each other.

Meanwhile, a less conspicuous manoeuvre was also underway as

Antiochos ordered the rest of his right-wing units to advance toward the

Ptolemaic lines behind the elephant screen. The king then personally took

command of his 4,000 cavalry and led them in a wide arc off his right flank.

This movement was important not merely to place Antiochos in a flanking

position but also to help the Seleukid king skirt the chaos that was sure to

ensue as the lines of charging elephants closed between the two opposing wings.

Keeping an eye on his elephants’ advance while he prepared

the rest of his wing to receive Antiochos’ attack, Ptolemy soon noticed a

worrisome sign of weakness from his mahouts, who seemed to be having a

difficult time goading all their animals into the assault. Some of the

elephants had turned aside, intimidated by the size and rapid onset of so many

Seleukid beasts, while others were startled by the noise of battle and the

sting of the arrows launched by Antiochos’ Cretans, who had moved up in direct

support of the Seleukid elephants. By the time the two corps met, Antiochos’

menacing approach had caused Ptolemy’s counter-attack to stall, sputtering into

an ineffective piecemeal advance. Nevertheless, the struggle between the two

lines was extraordinarily fierce when they finally came to blows.

Trumpeting loudly as they crashed into one another, the

ranks of Seleukid and Ptolemaic animals quickly became confused as friend and

foe mingled in a disorganized mass of jostling bodies, gouging tusks and

crushing feet. Slamming together with tremendous force, some of the smaller

beasts were knocked off their feet immediately in the brutal shoving match,

throwing the soldiers in their towers to a certain death amidst the furiously

churning feet below. As the animals locked their tusks together and attempted

to force their way bodily through one another, it was immediately obvious that

Ptolemy’s side could not win such a lopsided struggle. Outnumbered in elephants

as well as in Cretan archers, which both sides employed in relatively large

numbers and which now joined the fight in support, the elephant battle began to

shift drastically in Antiochos’ favour. Unable to do much to remedy the

deteriorating situation, Ptolemy could only send word to his stray mahouts,

urging them to join the struggle in a desperate attempt to stem the Seleukid

tide.

Antiochos, meanwhile, continued to move his cavalry out

around the flank of the fighting. Trotting along at a slow, measured pace, the

young king patiently watched and waited for his chance to strike.

With the rest of the Seleukid right wing forces now

approaching, the fighting that enveloped Ptolemy’s elephants became

increasingly desperate. Pikemen lunged and stabbed at their foes from atop

their towers while mercenary Cretans dashed here and there, loosing arrows and

dispatching fallen riders with deadly efficiency. All the while the air was

rent with the unearthly bellowing and roar of clashing elephants as well as the

pitiful cries of those wounded beasts which lay gored and slashed on the bloody

sand. Before long the Seleukid commander ordered his uncommitted riders to

deliver a final charge to break their foes. As they thundered into the line of

wavering enemy, the terror of facing still more Seleukid elephants proved too

much for the fragile morale of the Ptolemaic elephants, who could do little but

flee.

As the pharaoh watched in alarm from his position amongst

cavalry, the Ptolemaic elephant screen collapsed in a flood of terrified

animals and fleeing soldiers. Through this mass of panicked men and beasts,

Antiochos’ great Indian elephants burst, trampling dozens of foot soldiers

caught in their path and tossing their massive heads back and forth, goring and

flinging the scattering Cretans like broken rag dolls. With his screen in

headlong flight, dozens of war elephants now charged unobstructed toward the

Egyptian king’s exposed left wing.

Acting quickly, Ptolemy seized hold of an aide and began

reeling off orders for immediate dispatch to his commanders. Before the young

king could finish speaking, however, a cry went up from the men to his left,

who had spotted through the rolling clouds of dust and sand a powerful force of

enemy cavalry moving quickly off their left flank. Realizing the dual peril his

cavalry was in, Ptolemy judged that his men stood a better chance against

Antiochos’ horsemen than against his rampaging elephants. Ordering his troopers

to wheel to their left and meet the Seleukid cavalry charge head-on, Ptolemy

spurred his horse away from his disintegrating left wing. Behind him, the

enemy’s stampeding beasts closed in on the unfortunate soldiers of his royal

guard unit. Though it grieved him to leave his men to their fate, at the moment

the pharaoh had more pressing concerns bearing down on him in the form of

Antiochos and 4,000 Seleukid cavalry.

Unable to work their mounts up to full charge speed before

Antiochos’ men were upon them, some of Ptolemy’s troopers were completely

unhorsed by the force of the collision. Others found themselves isolated

amongst hundreds of enemy horsemen whose impetus carried them far into the

Ptolemaic formation. Though some of Ptolemy’s cavalry held their ground and

fought back ferociously, the sheer momentum of Antiochos’ onset cracked not

only the Ptolemaic formation, but also its morale. Though the 700 elite

guardsmen surrounding the young pharaoh performed heroically, beating back any

attempted inroads, Ptolemy could see from this area of isolated success that

his men elsewhere were faring far worse. Already the flanks of his formation

had begun to fray as panicked and wounded troopers fled to the rear in the face

of Antiochos’ numerically superior cavalry.

While the cavalry battle raged on the flank, the attention

of the men of the royal guard infantry was riveted on the scene unfolding to

their front as the ground began to tremble under their feet. Overwhelmed by the

number and strength of Antiochos’ Indian elephants, the surviving beasts of

Ptolemy’s mangled screening force fled back toward the safety of their left

wing. Preceding them, a cloud of frantic Cretan archers raced to escape the

crushing feet of their own side’s animals as well as those of the enemy. On the

heels of this exodus, dozens of towering Seleukid elephants charged forward

trumpeting furiously. As the guardsmen began to flee the deadly press, the

Ptolemaic elephants, riderless, blind with fear or maddened by wounds, crashed

back through their ranks. Unable to stand up to this kind of punishment, the

unit broke, dissolving into a mass of scrambling fugitives who flung away

shields and weapons in their desperate bid for safety.

As the rampaging animals ploughed into the fleeing

guardsmen, Antiochos’ Greek mercenaries, who had been slowly advancing toward

Ptolemy’s peltasts, suddenly launched their own assault. Slamming into the

disorganized peltasts, whose position next to the guards ensured that they had

not escaped the elephant onslaught unscathed or unshaken, the mercenaries made

short work of the already-collapsing infantrymen, who quickly panicked. As

these troops joined the rest of Ptolemy’s left wing infantry in headlong

flight, the pharaoh’s cavalry, disturbed to see virtually the entire wing in

retreat, began to break contact, galloping toward the rear with all the speed

they could muster from their tiring horses. Once begun, this domino effect

could not be stopped and soon even Ptolemy’s redoubtable bodyguard cavalry were

thrown back in disarray, forcing the young pharaoh to flee for his life.

Across the field, Echekrates, commander of the Ptolemaic right wing, squinted into the distance, trying to make out what was happening on the pharaoh’s wing. The messages he had been receiving indicated that a stiffly-contested elephant engagement was underway, but information had not reached him in some time. Resolving not to act until the situation on the left was clarified, Echekrates turned back to his front where he noticed with concern a flurry of movement from the Seleukid elephant line opposite his position. In minutes his fears were confirmed as dust plumes rose ominously into the air behind the line of advancing animals. Realizing he could no longer afford to remain inactive, Echekrates ordered his screening force of thirty-three elephants forward to meet the approaching enemy. Almost immediately, however, the commander saw that something was wrong. Though their advance began well, as soon as his elephants caught sight of Antiochos’ forty-two elephants, they shied away and could not be made to advance any further. Frustrated at this setback, Echekrates was forced to improvise.

He quickly ordered the 8,000 Greek mercenaries covering the

right flank of the Egyptian phalanx to advance against the Arab troops opposite

them. To prevent any interference, Echekrates left his skittish elephant screen

in place, hoping that their presence would at least temporarily block the

Seleukid animals from flanking the Ptolemaic phalanx while he moved his

right-wing troops ahead around them. Turning to the left, Echekrates cast one

final glance back toward his king’s position, but what he saw was not

encouraging. Beyond the massed lines of Ptolemy’s stationary phalanx, the

pharaoh’s entire left wing had disappeared, enveloped in a dense cloud of dust

and sand that seemed to be trailing off to the rear. Despairing at the fate of

his king, but determined to try to restore the situation, Echekrates ordered

his men to attack.

Ignoring the elephant stand-off near their flank, the

general’s Greek mercenaries pushed forward until they could clearly see their

opponents, a force of 10,000 Arab light infantry which Antiochos had placed to

guard the flank of the Seleukid settler phalanx. In the distance, Echekrates

had assumed direct command of the rest of the wing, including the Gallic and

Thracian infantry as well as the 2,000 cavalry on the extreme right, and had

carefully swung out around the right side of the advancing elephants. Having

apparently gambled everything on the success of the forty-two animals of his

elephant corps, the Seleukid wing commander had left his men fatally exposed to

Echekrates’ attack.

Dashing past the lumbering beasts, Echekrates led his Greek

and mercenary horsemen in a wide arc around the 2,000 Seleukid cavalry that capped

the enemy line. Following in the general’s wake around the flank were 6,000

Gallic and Thracian infantry, who suddenly broke away from the path of the

cavalry and veered straight toward the Seleukid line. Though it was a

calculated risk, Echekrates was forced to make it, as he had to pin down the

enemy cavalry before he could deliver his decisive blow. Racing away to the

right, the general could see that his infantry were taking casualties from the

deadly fire of Persian and Agrianian archers and slingers stationed next to the

Seleukid horsemen. Kicking his heels into his mount, Echekrates shouted for his

men to follow him as he tore across the sandy ground at full speed.

The Gauls and Thracians, meanwhile, were advancing quickly

toward the enemy through a hail of sling stones and arrows. Unencumbered by the

heavy armour and bulky weaponry of the phalangites, these men, formerly foes of

Macedon, were now highly sought-after in Hellenistic armies, and for good

reason. Not only were they masters of close combat, charging home with

frightening speed and force, but they had time and again proven their

usefulness, versatility and dependability on the battlefield. Now it was their

discipline and resolve that was being tested to the limit, as they sprinted toward

the daunting Seleukid line.

Whipping around the enemy flank, Echekrates suddenly wheeled

his troopers hard to the left, slamming them into the flank and rear of the

confused enemy. Just as the Thessalian officer’s cavalry crashed into the

scrambling Seleukid horsemen, the Greek mercenaries surged forward in a

powerful charge against the lightly-armed Arabs. These soldiers, though

admirably suited for skirmishing and ranged warfare, were not equipped or

trained to fight hand-to-hand in the frontline against battle-hardened

mercenaries. Inevitably, as the men in front began to fall at an intolerable

pace, those to the rear wavered and eventually took to their heels by the

hundreds. While this was going on, a cacophony of screaming and shouting

erupted off to the right. There the Gallic and Thracian troops, enraged by the

damaging missile fire they were taking as they neared the Seleukid line, raised

their war cry in deafening unison and flung themselves into the enemy archers

and slingers with suicidal abandon. Though some of the missile troops attempted

to fend off their attackers, untold numbers of them fell at the first shock as

the fierce Gauls and Thracians hacked into their ranks. With this shattering

blow, the entire Seleukid left wing broke and fled, pursued hotly by the

Ptolemaic troops, especially Echekrates, who drove his cavalry through their

broken ranks, cutting down hundreds.

While the battle still raged on both wings, the great

Seleukid and Ptolemaic phalanxes sat stationary in the centre, watching

uneasily as the struggle on their flanks unfolded. Inexperience and the

rashness of youth had robbed these men of their leaders, who were now too

preoccupied to issue the orders for them to engage. With Antiochos fading into

a cloud of dust on the rear horizon, Ptolemy lost in the chaotic pursuit and

both sides winning and losing on the wings, the officers of both phalanxes were

unsure of what course to take. Just at this moment, however, with the majority

of his left retreating in disorder and his right driving Antiochos’ left wing

before it, Ptolemy reappeared at the front of his phalanx to the ecstatic

cheers of the men. Though many had given him up for dead, Ptolemy managed to

escape the collapse of his left wing with a handful of bodyguards and race back

to the safety of his phalanx just in time to see the success of his right.

Knowing he had to seize his chance before it slipped away, the pharaoh rode out

in front of the men where his miraculous reappearance thrilled and

reinvigorated his centre and further disheartened the enemy, who now looked

vainly for the return of Antiochos. Without a moment to lose, Ptolemy ordered

forward his emboldened centre, which lurched ahead, eager to crush its

adversaries.

As the two massive phalanxes locked together, a fierce

struggle developed all along the line in which, to the surprise of many, not

the least of whom was Ptolemy, the Egyptian phalangites more than held their

own against Antiochos’ klerouchoi phalanx. Having been previously shorn of its

flank protection and now threatened with the looming prospect of an attack on

its exposed side, the morale of Antiochos’ military settlers plummeted. With

Ptolemy’s Greek mercenaries, Gauls and Thracians moving to the attack, it

should come as no surprise that the phalangites decided to flee from the pikes

of the Egyptians rather than suffer the slaughter that would surely occur if

they remained. Sadly for them, the spectre of dreadful slaughter appeared

regardless, for as panic spread down the Seleukid line and collapse followed

shortly behind, Echekrates and his cavalry thundered back onto the scene to aid

in the ghastly pursuit.

At the other end of the field, on the seaward flank of the

Seleukid army, panic eventually spread to the Silver Shields, who had fought

Ptolemy’s best phalanx soldiers to a standstill. Abandoned by their comrades,

the Silver Shields had no choice but to withdraw While the retreat was carried

out with discipline and order in some places, in others it had already devolved

into a mad dash for safety in which thousands were trampled or ridden down by

the enemy.

Having left his army to fend for itself, Antiochos, now far

to the rear, continued his pursuit of the exhausted Ptolemaic left, convinced

that the death of Ptolemy would deliver Egypt into his hands. Foolishly

rejecting all calls for him to turn back, it was only when one of his senior

officers drew the impetuous king’s attention to the great clouds of dust rising

from the distant battlefield that he realized his terrible mistake. Squinting into

the distance, Antiochos could make out dense plumes of dust rising thickly from

the field and leading toward the Seleukid camp. Though he knew well enough that

the rest of his army had already been defeated, an enraged Antiochos

nevertheless turned his winded royal squadron back toward the struggle. By the

time he reached the battlefield, however, nothing remained but the mangled

bodies of men, horses and elephants lying where they fell or dying where they

lay. With his forces now retreating off the field beyond recall, Antiochos

admitted defeat and sent word for his remaining soldiers to retire to Raphia.

There the king sullenly brooded on the idea that although he had been

victorious, the cowardice of his men secured his defeat.

Aftermath

It should come as no surprise that two young and

inexperienced kings were able to mismanage the handling of one of the largest

battles of antiquity. Handicapped by the uncertainty with which he viewed his

men, Ptolemy was from the start hesitant to seize the advantage which his

numerical superiority offered him. As it turned out, the resource which he felt

no hesitance in employing, his African war elephants, proved to be not only

completely ineffectual, but also dangerous to his own men.

On the other hand Antiochos, outnumbered by his more

powerful foe, may have subscribed too literally to Alexander’s hell-for-leather

principles of warfare. After all, Alexander was fighting mere Persians while

the young Seleukid king had a fellow Macedonian phalanx with which to contend. Thanks

to his overly-aggressive tactics and virtually non-existent contingency plan

for the rest of his men, a resounding success for Antiochos early on was later

transformed into the main cause of his abysmal defeat.

In all, Antiochos lost some 10,000 infantry and more than

300 cavalry, with 4,000 captured. Three of his elephants are said to have died

in the battle and two more from their wounds afterwards. As was often the case

in ancient warfare, Ptolemy escaped with the relatively light losses of only 1,500

infantry, 700 cavalry and 16 elephants. Though Polybios mistakenly states that

the rest of the pharaoh’s beasts were captured, such an outcome makes no sense

and is contradicted by a contemporary inscription which reveals that it was

Antiochos’ elephants that were captured.

Retreating northward, Antiochos decided to temporarily

forsake Koile Syria in order to focus his attention on regaining Asia Minor

from his rebellious general Achaios. According to the terms of a treaty signed

with Ptolemy, Antiochos evacuated all his conquests in Syria except for

Seleukia. Despite this momentary pause, Antiochos still considered Syria an

occupied part of the Seleukid Empire and would again roll the dice of war to

try to achieve its conquest. While the kings of Alexander’s former realm

squabbled in the east, a new power was rising in the west that would soon burst

forth to challenge the great Macedonians not for foreign conquests or Persian

gold, but for their very survival.