217 BC – During the Wars of the Diadochi at the Battle

of Raphia, Ptolemy IV Philopator of Egypt with 70,000 infantry, 5,000 cavalry,

and 73 war elephants fought the army of Antiochus III. The Antiochids suffered

just under 10,000 foot dead, about 300 horse and 5 elephants; 4,000 men were

taken prisoner. The Ptolemaic losses were 1,500 foot, 700 horse and 16

elephants. Most of the Antiochid elephants were taken by the Ptolemies.

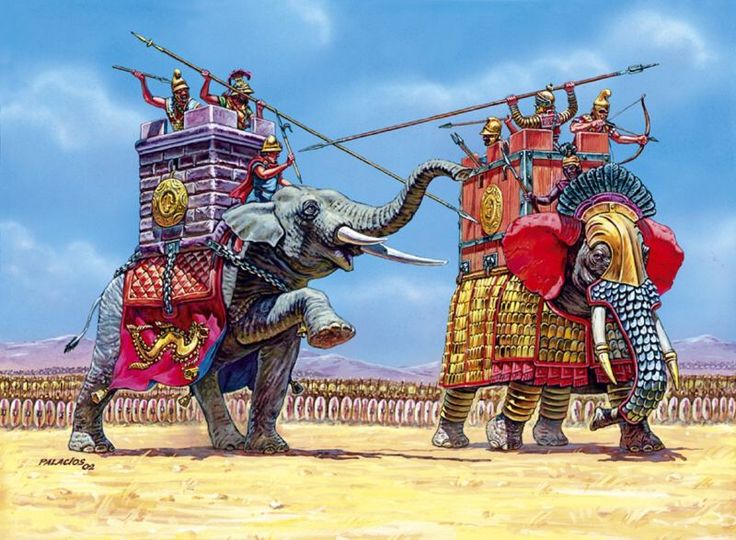

The soldiers in the howdahs maintained a brilliant fight,

lunging at and striking each other with crossed pikes. But the elephants

themselves fought still more brilliantly, using all their strength in the

encounter, and pushing against each other, forehead to forehead.

Polybios, 5.84

The Campaign

Despite the fact that Seleukos I owed his kingdom to the

extraordinary generosity of Ptolemy I, a disputed division of spoils after the

Battle of Ipsos erased any feelings of goodwill between the two leaders. The heart

of the problem was the allotment of Koile Syria to Seleukos instead of Ptolemy

during the apportionment of the Antigonid Empire. Ptolemy, who had worked to

capture Antigonid possessions in Syria in the weeks prior to the battle, was

tricked by Antigonos into retreating to Egypt, thereby missing the decisive

confrontation at Ipsos. Subsequently, when the victors met and Seleukos was

rewarded for his efforts in the battle with the province of Syria, a resentful

Ptolemy indignantly refused to withdraw his garrisons and vacate the territory.

Unwilling to press the issue at that time, Seleukos nevertheless laid the

groundwork for future conflicts by not relinquishing the Seleukid claim to the

region.

What followed, under less-tolerant leaders, was a century of

simmering resentment and outright hostility during which no fewer than three

wars were waged to resolve the question of which power would control the rich

Syrian coastlands. Often spilling over into Asia Minor, the Kyklades and

Europe, these conflicts frequently drew other regional powers into the struggle

with a chaotic web of shifting alliances as well as military and economic

support that did much to shape the bloody history of the eastern Mediterranean.

As the third century waned, however, a new generation of kings came to power in

Macedon, Egypt and Asia and a new age, the beginning of the end of the

Hellenistic world, began to unfold.

The clearest dividing line between the age of Macedonian

dominance and decline can be found in the last quarter of the third century.

With the accession of Antiochos III to the Seleukid throne in 223 and Philip V

and Ptolemy IV to the thrones of Macedon and Egypt just months apart in 221,

the governance of the three great monarchies of the day passed to three very young

and largely-untested kings. The successes and failures of these rulers would

prove decisive in the coming struggle for the survival of the Hellenistic

world.

After decades of warfare waged by Ptolemaic pharaohs and

Seleukid kings for the control of Syria, the newly-crowned Antiochos III

decided to settle the issue once and for all. Despite the fact that he had

inherited a realm riddled with internal problems, including smouldering

rebellions at both ends of his massive empire, Antiochos sought first to seize

control of Syria. By snatching this prize from an already militarily weak

Ptolemaic empire, Antiochos could further cripple his adversaries while laying

the groundwork for an eventual invasion of Egypt itself.

Having dispatched his top commander to the east with a large

army to deal with a rebellious general, a subsequent shortage of battle-ready

troops led Antiochos to advance on Ptolemaic Syria with only a modest-sized

force. Nevertheless, marching boldly into the region in the summer of 221, the young

king moved swiftly to try to catch his enemy off guard. His efforts were all in

vain, however, as Ptolemy’s commander in the province, an Aitolian general

named Theodotos, had been alerted beforehand to the Seleukid king’s designs and

was able to erect defences and stoutly garrison many of the region’s

strongholds. Unprepared for Theodotos’ spirited defence and unable, due to the

relatively small size of his force, to strategically pin and flank the

Ptolemaic positions, Antiochos eventually withdrew with some loss after a

series of reverses.

Having learned that the forces he sent east had been

defeated, Antiochos decided to secure his rear before again attempting to

subdue Syria. Taking command of the army himself, in early 220 Antiochos set

off toward Mesopotamia, where he met the rebels in battle. Decisively defeating

them and restoring the region to Seleukid control, he then turned his attention

back to the Mediterranean coast, where he seized the important port city of

Seleukia in the spring of 219. As the campaigning season rolled on and

Antiochos prepared his men for a further advance, an unexpected piece of good

fortune energized the king’s plans. Theodotos, alienated by the short-sighted

politics of the Egyptian court, decided that his future was brighter in the

Seleukid camp. He consequently sent word to Antiochos that he was prepared to

surrender his charge, an offer which the young king accepted with delight.

Advancing confidently southward, Antiochos was able to

occupy much of Syria, though some fortresses and cities remained obstinately

loyal to Ptolemy. Instead of barrelling on toward Egypt, however, Antiochos

decided to place the holdouts under siege in order to consolidate his control

of the region. While this was going on the pharaoh and his ministers were

scrambling to mitigate the disastrous effects of Theodotos’ betrayal. Having

depended almost entirely on that general and his forces to hold the Syrian

frontier, the leaders in Alexandria were now forced to take action to remedy a

deadly situation that had been developing unchecked for some years. With their

military strength centred chiefly on their powerful fleet, the Ptolemaic

government had over the years allowed their standing army to fall into such

disrepair that it was no longer a match for the veteran forces of Antiochos.

Desperate measures were now hastily put into place to recruit and train

thousands of troops to bolster the small, but effective, European core of the

royal army. In an attempt to match the experience and sheer number of men that

the Seleukid king could muster, recruiting officers were dispatched throughout

the eastern Mediterranean with plenty of that quintessentially Ptolemaic

problem-solver: gold.

To buy themselves some much-needed time for these measures

to take effect, the Egyptians approached Antiochos at the end of 219 with a

proposal for a four-month ceasefire. Unexpectedly, Antiochos agreed, probably

with the hope of bargaining from a position of strength and gaining all of

Syria without a fight. The Egyptians, however, strung the Seleukid monarch

along, using the time to frantically train and equip soldiers and contract

mercenaries, even going so far as to throw open their recruitment to native

Egyptians. After negotiations broke down over the winter, Antiochos resumed his

war in the spring of 218, though he spent the majority of the year pacifying

the remaining strongholds of Ptolemaic resistance in southern Syria.

Meanwhile, Ptolemy’s hurried campaign of improvement and

enrolment had been massively successful, supplying the pharaoh with a powerful

army of adequately trained soldiers. Led by some of the most experienced

officers he could recruit from throughout the Greek world, by the early summer

of 217 Ptolemy was finally prepared to take the fight to Antiochos. While the

Seleukid king moved his men through Koile Syria, stamping out the last remnants

of Ptolemaic resistance, he received the jarring news that Ptolemy had taken

the field with a monstrous force and was advancing with unexpected vigour

northward out of Egypt. Gathering together every available man, Antiochos

marched without delay to meet his foe; eventually finding him encamped along

the main north-south highway near Raphia in southern Syria. There the pharaoh

sat, defiantly barring the way south and directly challenging Antiochos, whose

claims on Ptolemaic Syria were about to be put to the ultimate test.

The Battlefield

The battlefield of Raphia, like so many battlefields of

antiquity, was located on or near a major regional highway. A vital goal of

Ptolemy’s campaign was to occupy this route, as it not only facilitated the

rapid movement of thousands of troops but also directly linked the largest and

most important cities of the area. Sitting astride the road, which led to the

Egyptian fortress-city of Pelusium, Ptolemy arranged his forces so as to block

the plain and prevent Antiochos from any further advance.

Though there is little mention of any obstacles or

significant geographic features in Polybios’ account of the battle, it has been

suggested that rising dunes and drifting sands may have flanked the

battlefield, then as today. This would have placed a definite limit on the

space available for cavalry manoeuvres, though from Polybios’ text, the

battlefield seems to have been an open desert plain near the sea coast.

Armies and Leaders

On 22 June 217, the armies of the Seleukid king, Antiochos

III, and the Ptolemaic pharaoh, Ptolemy IV, collided in a death struggle at

Raphia in southern Syria. With almost 150,000 soldiers taking part in the conflict,

not to mention some 175 elephants, Raphia would become one of the largest

battles of the pre-modern era. Just as important as the size of the engagement,

however, was the composition of the armies involved.

In the century since their creation, the kingdoms arising

from the eastern regions of Alexander’s empire were forced by their distance

from the manpower reserves of Europe to compromise in the construction of their

armies. Rather than rely solely on their relatively few Macedonian phalangites,

they instead made extensive use of conquered peoples. The Seleukids especially

found that an abundance of missile and light-armed troops conscripted from the

provinces of the former Persian Empire typically afforded their phalanx greater

protection and flexibility. The unique battlefield expertise of the different

troop types which Hellenistic leaders were able to recruit was proven time and

again to be invaluable. While this shift toward lighter native troops had

tactical implications on the battlefield, the large-scale conscription of

natives from across the broad Seleukid and Ptolemaic spheres of influence

presented a different kind of challenge for commanders. An idea of the

difficulties of manoeuvring these multinational forces can be found in the inspirational

pre-battle speech given to the troops by both Ptolemy and Antiochos, which had

to be relayed to each of the various nationalities through numerous different

interpreters and translators.

Despite such easy access to large numbers of native infantry,

virtually all eastern Hellenistic leaders shared a preoccupation with the

judicial utilization of any Greek and Macedonian settlers they could attract or

who had previously settled in the region. Known as klerouchoi, or military

settlers, these men traded military service for land and as a result were

soldiers of varying quality, especially in Ptolemaic Egypt. Apart from these

dilettantes, only a comparatively small group of professional soldiers formed

the core of either of the great armies that clashed at Raphia. Nevertheless,

the phalanx remained a crucial element of Hellenistic warfare in the east,

despite the increasingly non-professional character of its soldiers.

For several days the two forces camped some 5.5 miles apart

while intelligence and supplies were gathered, until Antiochos abruptly decided

to escalate matters. Seizing a chance to place his army in a more favourable

position, he thrust his men forward to within a half mile of Ptolemy’s camp.

From this dangerously close vantage point each force warily eyed the other as

skirmishing and raiding ensured that the situation remained tense. Such a

stand-off could not last forever, especially as the supplies of both sides

began to dwindle. It therefore came as no surprise to Antiochos when his officers

informed him one morning of movement in front of the Ptolemaic camp. By the

time the king was himself able to get a look at the suspicious activity it was

clear that Ptolemy was drawing his men up for battle. Antiochos quickly ordered

his men to do likewise.

Deploying across the entire breadth of the plain, the kings

spent the early morning hours of 22 June positioning their forces for maximum

effect. As the first to deploy, Ptolemy was confident in his men, and for good

reason. Thanks to the industry of his ministers and officers, the pharaoh

arrived at the battlefield with some 70,000 infantry, 5,000 cavalry and 73

elephants. Confident but not rash, Ptolemy knew he would need every man in his

gargantuan army in order to secure victory against the more experienced and

highly-trained troops of his foe.

Forming the extreme left of his line from 3,000 Libyan,

Egyptian and royal guard cavalry, Ptolemy took up position there, opposite

Antiochos. He then extended his line to the right by placing a force of 3,000

infantry known as the Royal Guard, followed by 2,000 peltasts adjoining a unit

of Libyans trained as phalangites. Following the time-honoured tradition in

Macedonian armies, Ptolemy placed his phalanx, a powerful block of 45,000

phalangites, in the centre of his line. Staggering in its size, the Ptolemaic

phalanx was unfortunately not the uniform fighting force it may have seemed.

While the mainstay of his entire line was a phalanx of 25,000 Macedonian and

Greek military settlers or mercenaries of adequate quality, the remaining

20,000 soldiers were a hastily-assembled and unpredictable force of native

Egyptians, as yet untested in battle. Though by no means untrained, these

troops lacked the experience of the mercenaries and the immediate warlike

tradition of the settlers.

The right wing of the Ptolemaic army, under the command of

the Thessalian mercenary officer Echekrates, was composed of 8,000 Greek

mercenaries adjoining 6,000 Gallic and Thracian soldiers. On the extreme right

end of the line was a superbly-trained force of 2,000 Greek and mercenary

cavalry. To secure his flanks, Ptolemy strung 40 elephants across the front of

his left wing, supported by 2,000 Cretan archers. His remaining 33 animals he

placed in front of the cavalry on his right wing.

Across the field, Antiochos’ deployment mimicked Ptolemy’s

in certain key ways. Taking up position amongst the right-wing cavalry,

directly facing the Egyptian monarch, Antiochos placed 2,000 cavalry at the

extreme end of his line flanked by an advance force of another 2,000 horsemen

positioned at an angle to his own unit. To the left of these he placed a band

of Greek mercenaries adjoining another unit of European mercenaries trained in

the Macedonian fashion. In his centre the Seleukid king positioned his most

dependable soldiers, a 10,000-man-strong unit of phalangites known as the

Silver Shields. Next to these were stationed a phalanx of 20,000 military

settlers.

On his left wing Antiochos was forced to extend his line,

placing many light units and even missile troops along his front. Adjoining the

klerouchoi phalanx was a motley collection of 10,000 Arab light infantry,

followed by a further assemblage of 5,000 light-armed troops from the eastern

provinces. Filling out the rest of the front were several thousand missile

troops before the line was finally capped by a force of 2,000 cavalry. Like

Ptolemy, Antiochos placed his elephants across his wings, with 60 animals

supported by 2,500 Cretans covering his right, while the remaining 42 screened part

of his left.

All told, the combatants’ dispositions at the outset of the

Battle of Raphia were fairly well-matched. Though Ptolemy comfortably

outnumbered Antiochos in phalanx infantry, almost half of those troops were the

Egyptian phalangites, a thoroughly unknown commodity. Despite this somewhat

tenuous advantage in heavy foot, Antiochos retained a slim superiority in

cavalry and a large one in elephants, outnumbering Ptolemy’s beasts 102 to 73.

As the struggle began on that sweltering afternoon in late June 217, success or

failure rested entirely with the two young kings who now stood poised to launch

the largest battle between Hellenistic monarchs since the great confrontation

at Ipsos more than eighty years earlier.