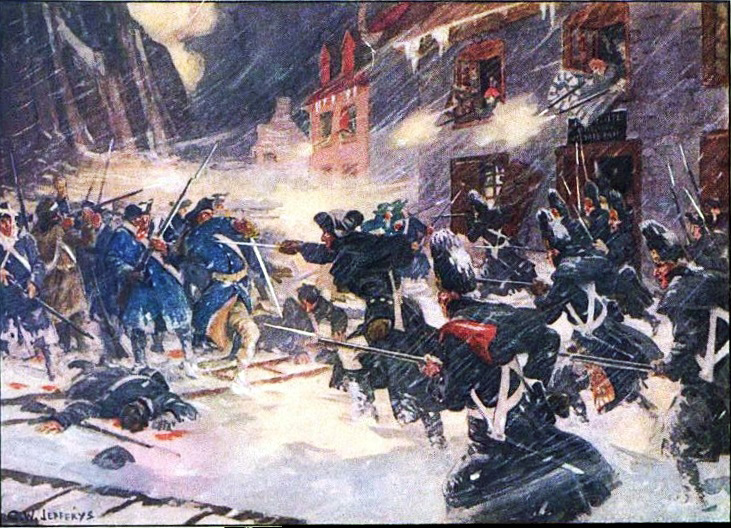

British and Canadian forces attacking Arnold’s column

in the Sault-au-Matelot painting by C. W. Jefferys

Invasion routes of Montgomery and Arnold.

In 1775, five years before Karl von Clausewitz was born, the

Second Continental Congress was already applying the Prussian’s dictum that war

is only a continuation of national policy by other means. Early in that session

the Congress made two commitments that were to change the colonies’ form of

resistance from rebellion to all-out war. The first was to appoint a committee

to draw up the organization of a Continental army. Then, on 15 June, George

Washington was named “to command all the Continental forces, raised or to be

raised, for the defense of American liberty.” At the same time it appointed

Washington general in chief of the army, Congress appointed other officers.

Four were named major generals: Artemas Ward, Israel Putnam, Charles Lee, and

Philip Schuyler.

Washington assumed command of the army when he arrived at

Boston on 3 July. By then the action at Bunker Hill had established in

everyone’s mind the idea that pitched battles were to be the realities of the

future, so Washington set about preparing the army for that type of warfare.

That meant instilling discipline, an uphill fight in the face of the conviction

so endemic to New Englanders that any man was as good as another. This concept,

inspiring as it may have been in a town meeting, had an opposite effect on

Washington’s efforts to build a force that would stand up in battle. Organizing

a disciplined army occupied Washington’s attention for a long time after his

arrival.

Long before the French and Indian War (1754-63), one word

had always spelled trouble for the more northern settlements of New

England—Canada. From there, for generations, had come the war parties, led or

encouraged by the French, that had savaged the frontier and the interior with

tomahawk and torch. The treaty of 1763 brought peace, but relief for the

colonies was short-lived. The Quebec Act of 1774 that recognized the rights of

the Canadian French had an alarming effect on Virginia, Connecticut, and

Massachusetts, because a provision of the act extended Canada’s boundaries to

the Ohio River, thus giving back to Canadians lands already being settled by

Americans in regions like the Ohio Valley.

In 1775 the Continental Congress sought a peaceful solution

to the threat of British-occupied Canada. On 29 May it appealed in a letter “to

the oppressed Inhabitants of Canada” to join “with us in the defense of our

common liberty.” Like many such ideal solutions, this one didn’t work. The

Canadians turned a deaf ear. There were those in Congress, however, who felt

that if the Canadians were of a mind to stay loyal to Britain, they might be

more responsive to things like invasion and occupation. For the moment cooler

heads prevailed, and on 1 June Congress went so far as to resolve that “no

expedition or incursion ought to be undertaken . . . against or into Canada.”

The impasse was not to last.

Earlier, on 10 May 1775, Ethan Allen and eighty-three of his

Green Mountain Boys, accompanied by a Massachusetts-commissioned colonel named

Benedict Arnold, “stormed” half-ruined Fort Ticonderoga on Lake Champlain,

forcing its commander to surrender its half-invalid garrison to Allen “in the

name of the great Jehovah and the Continental Congress!” Congress did nothing

at first to follow up the success. Though Arnold and Allen had their personal

differences, both were convinced that Canada was vulnerable to invasion. Arnold

made a written report to that effect on 13 June, and ten days later Allen, on

the floor of Congress in Philadelphia, presumably agreed. In any case, Congress

revised its policy toward Canada on 27 June. General Philip Schuyler was

directed “to take possession of St. Johns, Montreal, and . . . other parts of

the country.”

Schuyler’s orders sounded more like permission—”if General

Schuyler finds it practicable, and that it will not be too disagreeable to the

Canadians”—and were in keeping with the lack of a strategy for invasion. Though

Congress did not produce a grand strategic plan, it did develop, in piecemeal

fashion, two expeditions, each with a logical objective: in the west it was Montreal,

in the east Quebec. By taking these two objectives and defeating the weak and

scattered British forces, the “fourteenth colony” could be brought to terms. It

was not an unsound strategy, and it could have succeeded. That it did not may

be attributed mainly to three factors: unexpectedly rough terrain, the forces

of nature, and the abilities of General Guy Carleton, governor of Canada and

commander of the British forces.

After much delay in preparations, the expedition in the west

began on 25 August 1775 when Brigadier General Richard Montgomery, in place of

the ailing Schuyler, advanced northward up Lake Champlain. At age thirty-seven

Montgomery was a leader possessed of the essential qualities that Schuyler

lacked: aggressiveness, decisiveness, personal magnetism, physical and moral

courage, and the strength to endure the hardships of a wilderness campaign. He

had been born the son of a baronet in Ireland, had been educated at Trinity

College, Dublin, and at seventeen had taken up a military career. He had fought

with the British army at Louisbourg in 1753, and under Geoffrey Amherst at

Ticonderoga, Crown Point, and Montreal. In 1772 he resigned his commission,

moved his home to America, settled down as a gentleman farmer near Kings

Bridge, New York, and married Janet Livingston, daughter of a prominent New

York family. In June 1775 he accepted a commission as a brigadier general in

the Continental army, left his young wife on her estate, and went to join

Schuyler.

From the outset Montgomery might well have concluded that

the luck of the Irish had abandoned him. The expedition consisted of about

1,700 Connecticut and New York militia, untrained, undisciplined, and likely to

flee upon hearing the word “ambush”—as they had done on one occasion already. By

16 September, however, Montgomery had reasserted control and headed for Fort

Saint Johns, his first objective. This small outpost, together with Chambly,

ten miles to the north, commanded the Richelieu River and thus the approaches between

Lake Champlain and Sorel on the Saint Lawrence. In spite of its strategic

importance, Saint Johns (Saint Jean in French) had been only a frontier outpost

with a couple of brick buildings and a storehouse until British General

Carleton had reinforced the garrison to a total of 725 regulars and militia and

ordered the commander, Major Charles Preston, to construct two redoubts, which

made it a formidable fort.

Montgomery moved his makeshift flotilla of a schooner, a

sloop, and a collection of “gondolas, bateaux, row-galleys, pirauguas, and

canoes” northward past Ile Aux Noix, and disembarked his force to take Saint

Johns. He sent out detachments to cut the road to Montreal, twenty-five miles

to the north, and to forage.

When Montgomery had assessed the situation, it was clear

that his motley force, now reduced by sickness to 1,100 effectives, could not

take Saint Johns by assault. He therefore began to entrench, emplacing his two

guns and some small mortars. The conditions for the besiegers were difficult.

The ground everywhere was swampy and entrenchments quickly filled with

knee-deep water. It was early October, and the cold rains were becoming

intolerable. In a letter Montgomery wrote that “we have been like half-drowned

rats crawling through a swamp.” Supplies, both food and ammunition, were

running out. To make things worse, the British in their fort were holding out

steadfastly in spite of incoming artillery rounds.

For General Guy Carleton, the reinforcement and

fortification of Saint Johns had been his first priority. Earlier, however, he

had discovered to his dismay that his French subjects were more neutral than

loyal. He had counted on the Quebec Act (which he had sponsored) to win over

the French Canadians, but in 1775 he had found them generally unwilling to

enlist in the British forces. Moreover, Carleton had sent all but 800 of his

regulars to Boston. In June 1775, realizing his precarious position, he declared

martial law and began to mobilize all the British and Scots he could muster. He

was a competent general as well as an excellent administrator. After

strengthening Saint Johns, he personally took over in Montreal and began to

rally what forces he could in the west.

By 18 October, when things were looking bleak for the

Americans, a near-miracle occurred. The night before, two American bateaux

mounting nine-pounder guns had sneaked past the defenses of Chambly and had

reported to Montgomery. Montgomery therefore decided to take Chambly, the

weaker garrison, first. With their guns in position, Montgomery’s detachment of

50 Americans and 300 Canadian allies was able to surround the fort at Chambly.

After a few artillery rounds had penetrated the walls, the British commander

surrendered. Among the stores captured were six tons of powder, 6,500 musket

cartridges, and 125 muskets. Of no less importance were eighty barrels of flour

and 272 barrels of foodstuffs.

The captured stores enabled Montgomery to lift the spirits

of his men enough to make the maneuver he needed to push the siege of Saint

Johns itself. On 25 October he got a battery of twelve-pounders and lighter

artillery into position on a hill that dominated the fort. The British

commander, Major Preston, continued to hold out for a while, but Canadian

prisoners, released by Montgomery, convinced him that his situation was

hopeless. Preston surrendered Saint Johns on 2 November, having held out for

fifty-five days. The garrison laid down its arms, and officers and men were

paroled; the Canadians went home, and the British regulars were sent to a port

where they could sail for England.

Three days later, Montgomery took up his slow march to

Montreal, where Carleton awaited him with a tiny force of 150 regulars and

militia. On 11 November Montgomery began to surround Montreal by landing a

detachment north of it. On the same day Carleton, recognizing the town to be

indefensible, set sail down the Saint Lawrence, carrying with him all that he

could of the military stores. He almost failed to make it. Near Sorel, adverse

winds and American shore batteries brought his little flotilla to bay, and

Carleton’s ship, the brigantine Gaspe’e, had to surrender. Carleton escaped in

civilian clothes with two of his officers. Montreal was surrendered to

Montgomery by its citizens on 13 November.

In late summer of 1775 newly appointed General Washington

had come to realize that the western expedition to take Montreal was only half

a strategy: Quebec would still command the Saint Lawrence River, gateway to

Montreal and inner Canada. Moreover, so he reasoned, an invasion in the east

against Quebec, if timed in coordination with that of Montgomery against

Montreal, would force Carleton to fight on two fronts, with all the embarrassment

that went with it.

Washington soon became convinced that the most promising

invasion route was a waterway, specifically up the Kennebec River, thence to

the Chaudière River, which emptied into the Saint Lawrence not far from Quebec.

Much of the route had been mapped and described in his journal by Captain John

Montresor, a British army engineer, in 1761. Montesor’s map turned out to be

incomplete, however, and the consequences of relying on it would later prove

nearly disastrous. Nevertheless Washington had no alternative, for in 1775 huge

areas of the Maine and Canadian wilderness were not mapped at all. Washington

was aware of the hazards of the expedition, but he had confidence in the

commander he had selected, Benedict Arnold, to whom he offered a commission as

a colonel in the Continental army and the command of the eastern expedition to

take Quebec. Arnold jumped at the opportunity.

Who was this Benedict Arnold who caught Washington’s eye at

the right time? In the first place he was a born leader. One of his soldiers

voiced what all believed: “He was our fighting general [at Saratoga]. . . . It

was ‘Come on boys!’ twarn’t ‘Go boys.’ He was as brave a man as ever lived.” He

had an eye for sizing up a tactical situation, and he was as skillful in planning

as he was bold in executing his plans. He was strong-willed, a quality which

made him resolute in adversity. In sum, he showed most of the soldierly

virtues, and it was mainly the fatal flaws of excessive ambition,

hypersensitivity, and love of glory that would eventually bring him to ruin.

In 1775 Arnold, from a well-to-do Connecticut family, was

thirty-four years old. He had gone adventuring in the French and Indian War.

Later, he settled down in business after selling the family property. As a merchant

he had sailed his own ships to the West Indies and Canada, and he later sold

horses in Montreal and Quebec. At the outbreak of rebellion he was prosperous,

“the possessor of an elegant house, storehouses, wharves, and vessels. . . .

Rather a short man, he seemed, but stocky and athletic, and very quick in his

movements. Raven-black hair, a high, hot complexion, a long, keen nose, a

domineering chin, persuasive, smiling lips, haughty brows, and the boldest eyes

man ever saw, completed him” (Justin Smith, Our Struggle for the Fourteenth

Colony). Completed him indeed! Benedict Arnold was not a man easily overlooked.

Small wonder that the man and his reputation had come to Washington’s

attention.

In August Arnold had already been dealing with Reuben Colburn,

a Kennebec boat-builder, to have two hundred bateaux built. On 3 September

Washington approved an order for the boats and stores of provisions, and two

days later the organization of the expedition was announced in army orders. The

detachment was to consist of two battalions of five companies each, the men to

be volunteers who should be “active woodsmen well acquainted with batteaus.”

That specification was never filled; with the exception of riflemen, the

volunteers assigned were from New England regiments which they had joined from

their farms. The detachment also included three companies of riflemen: Captain

Daniel Morgan’s company of Virginians and two companies from Pennsylvania under

Captains Matthew Smith and William Hendricks, 250 riflemen in all. The total

strength of Arnold’s force came to about 1,100, counting miscellaneous troops,

which included 6 “unattached volunteers,” one of whom was nineteen-year-old

Aaron Burr.

One leader among the riflemen had already achieved a

reputation for bravery and ability: Captain Dan Morgan, a dyed-in-the-wool

product of the frontier wars. Over six feet tall, broad-shouldered, with a

solidly muscled body, he was renowned for his strength (exerted in his youth in

scores of tavern brawls) and woodcraft, learned the hard way from the Indians.

He had been a wagoner in Braddock’s expedition, and the story of his laying out

a British officer with his fist for striking him with his sword was a

well-known frontier tale. Flogged by the British for that military offense, he

bore a bitter hatred for them. The “Old Wagoner,” as Morgan was called, was a

natural leader, and his grasp of tactics was phenomenal. He was admired by his

men—he could lick any one of them—and they would follow him anywhere. He was

further noted for his blunt speech and quick temper, both of which covered a

kindly nature and a rough-hewn sense of humor.

When Arnold reached Gardinerston on 22 September, he found

to his dismay that the two hundred bateaux—flat-bottomed boats with flared

sides and tapered ends, propelled by oars or paddles in deep water and pushed

by poles in rough or shallow water—had been hastily made of green lumber. They

would be heavy and clumsy craft for portaging, and difficult to handle in white

water. But Arnold was stuck with them, and even had to order twenty more. On 25

September the expedition left Fort Western—today’s Augusta, Maine. Arnold

divided his force into four divisions. The first division was composed of the

three companies of riflemen commanded by Captain Morgan. Morgan’s riflemen were

preceded by two scouting parties, led by Lieutenants Steele and Church. The

other three divisions followed Morgan’s between 26 and 28 September, departing

in numerical order. Arnold went ahead of the main body, and he seems to have

been ubiquitous, showing up anywhere his command presence was needed.

Thereafter matters developed as follows:

30 September 1775: After passing Fort Halifax the divisions

had to make their first portage around Ticonic Falls, shoulder carrying a

hundred tons of boats and supplies.

3 October: Main body had to pass through a “chute” of

vertical rock banks to get past Showhegan Falls. Bateaux had to be pushed and

carried through.

4-8 October: After the passage of the Bombazee Rips (rapids)

the divisions faced the dreaded Norridgewock Falls with its three “pitches”

each separated by a half mile. The bateaux began to give out. Seams were

wrenched open and water poured through the cracks. Colburn and his artificers

came up, and “the seams had a fresh calking, and the bottoms were repaired as

well as possible.” The provisions casks had also been split open and washed

through with water. “The salt had been washed out of the dried fish . . . and

all of it had spoiled. The casks of dried peas and biscuit had burst and been lost.

. . while the salt beef, cured in hot weather, proved unfit for use.”

9-10 October: Curritunk Falls—cold rains set in.

11-17 October: The Great Carry Place, with its three ponds

and four portages. The Kennebec River was left behind. Fierce winds and snow

squalls. Ponds choked with roots, forests filled with bogs, men up to their

knees. Lieutenants Steele and Church reported in. Steele’s last five men

staggered in, starving wretches at life’s end. The divisions reached Bog Brook,

which flows into Dead River.

19-24 October: Thirty miles on the Dead River. Unaccountably

Greene’s division (commanded by Lt. Col. Christopher Greene, a distant kinsman

of Nathanael Green) passed Morgan’s riflemen, who stole their food. On 21-22

October a hurricane-spawned rainstorm turned the river into a raging flood.

Whole country under water. Many bateaux lost. A conference was held to

determine if march should continue; Arnold’s eloquence and show of determined

courage made them decide to go on.

25 October: Enos’s fourth division elected to turn back, and

would not yield its flour to Greene’s starving men, who were subsisting on

candles mixed in flour gruel. Expedition was reduced to seven hundred men out

of original eleven hundred. [Enos was later court-martialed for desertion.]

25-28 October: Height of Land, “prodigious high mountains,”

the divide where streams flow north to the Saint Lawrence, south to the

Kennebec. South of Lake Megantic, Arnold’s men were betrayed by Montresor’s

map, which didn’t show Rush Lake, Spider Lake, or False Mouths of Seven-Mile

Stream (Arnold River). They tried to skirt the two lakes and wandered among

swamps until they almost perished.

1-3 November: Starving men ate soap, hair grease, boiled

moccasins, shot pouches, a company commander’s dog. Men staggered on, supported

by their muskets. On 3 November a miracle: a herd of cattle arrived, driven by

men dispatched by Arnold, who had gone ahead to scour the country. The cattle

were manhandled to slaughter, roasted, torn to bits, and eaten “as a hungry dog

would tear a haunch of meat.”

4 November: Reached Sartigan, the wilderness left behind

them. Arnold’s provisions, left there for them, gobbled up so fast that men

became ill, and three died.

5 November: Left the Chaudière below Saint Mary, headed for

Point Levis, across the Saint Lawrence from Quebec.

On 9 November 1775 Canadians at the Saint Lawrence were

astounded to see a ragtag column of six hundred survivors hobbling toward the

river, “ghosts with firelocks on their shoulders.” As they streamed from the

woods they at first spread alarm, though that soon turned into admiration when

Canadians learned of the conditions of the heroic march.

Arnold’s march has been compared to Xenophon’s march to the

sea and Hannibal’s crossing the Alps. Yet what did this band of heroes find to

greet them after enduring such incredible hardships? An indefatigable Arnold

was busily rounding up boats, canoes, and scaling ladders so that they could

cross the Saint Lawrence—under the very guns of the frigate Lizard, the

sloop-of-war Hunter, and four other armed craft—and storm the walls of Quebec!

Hector Cramahé, Carleton’s lieutenant governor and governor

of Quebec City, had seen to it that the Point Levis shores of the Saint

Lawrence across from Quebec had been swept clean of any boats the Americans

might use to cross the river. But Arnold, as usual, was equal to the emergency.

His scrounging parties, with the help of friendly Indians, soon assembled a

mixed flotilla of about forty canoes and dugouts. By 10 November he was ready

to make a night crossing, his only chance to get by the British warships in the

river. A heavy gale came up, however, which made the river impassable for

Arnold’s light craft, and he had to wait until 9:00 P.M. on the thirteenth for

the storm to subside. Then Arnold ferried his men over in shifts, slipping

silently past the anchored British ships to land in Wolfe’s Cove, where in 1759

the British General James Wolfe had landed in his successful operation against

Quebec. Arnold got all his force across except for 150 men who remained on the

Point Levis side until the next night.

Having led his men way up to the Plains of Abraham on the

road Wolfe had used sixteen years before, Arnold halted them a mile and a half

from the city’s walls. There they took shelter until daylight. Unknown to

Arnold, however, the firebrand Allan MacLean had brought eighty of his Royal

Highland Emigrants to Quebec and had taken over military command. The garrison

was an improvised force of about 1,200 men, including militia and sailors and

marines from the ships. The city MacLean had to defend has been described as rising

grandly from a majestic river, the vast rock towers high and broad. On the

north were plains between the promontory and the Saint Charles River, which

flowed into the Saint Lawrence east of town. Along the Saint Lawrence, slopes

tapered off from the rocky sides to the river, affording passage to the Lower

Town, which was guarded by double palisades and, behind them, a blockhouse. On

the south side Cape Diamond rose 300 feet above the river. In the Lower Town

itself there were wooden barriers blocking the Sault au Matelot, a narrow

street which led to steep passages to the Upper Town. The latter dominated the

greater part of the city. It was protected by a 30-foot wall along its whole

western and northern sides. There were six bastions with artillery and three

main gates: on the north the Palace, in the center Saint John’s, in the south

Saint Louis.