The fall of Constantinople in 1453 (only 3 years before the

Ottoman siege at Belgrade) sent panic and fear throughout Europe and the

Christian world. The loss of Constantinople was regarded as a calamitous

setback for Christian Europe and the crusades. The victorious Sultan Mehmet II,

encouraged by his momentous victory at Constantinople, began an advance into the

Balkans and northward in the hopes of defeating Hungary and reaching Western

Europe. Mehmed II would take Serbia in 1454-55; and the following year with an

army estimated to be 70,000 strong (other historians have estimated that

Mehmed’s army may have been between 100,000-300,000 men), he launched what

would be a long and arduous march to Belgrade.

Belgrade (Nándorfehérvár) was a key stronghold of the

southern defense system of medieval Hungary. The epic battle between the

Ottoman Empire and Hungary would come to significantly influence the subsequent

history of Europe and the spread of Ottoman domination in the Balkans. János

(John) Hunyadi, an influential and famous Hungarian military commander,

politician and noble, took the responsibility for coordinating and controlling

the defensive operations along the southern borders of Hungary (a position he

was appointed to in 1441). Hunyadi, knowing of the Ottoman advance in the

Balkans, left 7,000 of his soldiers in Belgrade to build and strengthen its

defensive capabilities in May of 1456. In the buildup to the Ottoman siege,

John of Capistrano, a Franciscan monk appointed by the pope to recruit as many

troops as it was possible, crisscrossed the Kingdom of Hungary and Western

European powers to raise a volunteer force. By June, 1456 Capistrano’s army and

the Hungarian forces (numbering approximately 45,000-50,000 in total) arrived

in Belgrade and began to take up their defensive positions north of the city.

Hunyadi was able to maintain his pre-eminent position for

several years to a considerable degree due to the ever-present Ottoman menace.

The defeat of Kosovo Polje was followed by a pause in hostilities. Sultan

Murad, who had business to look after elsewhere, signed a treaty with the

Hungarians in 1450 and this was confirmed by his successor, Mehmed II

(1451-1481). However, it was soon apparent that the accession of Mehmed meant

the beginning of a new phase of Ottoman expansion, which was to be much more

successful than the previous ones. The first waves of this resurgent military

threat soon reached Hungary. Constantinople fell in 1453, and Mehmed

immediately transferred his residence from Adrianople to the newly conquered city.

In 1454, when the peace of Oradea expired, he attacked Serbia and laid siege to

Smederevo, Brankovi.’s capital. In the following year he renewed his attack,

this time occupying the whole of Serbia with the exception of Smederevo. As the

expedition of 1456 was to be directed against Belgrade, it was not surprising

that Hunyadi would once again be pushed to the forefront of events as the

potential saviour of the kingdom. His reputation may have been shaken by his

defeats since 1444, but he was indisputably the only man capable of

successfully opposing the Ottomans.

The preparations for a counter-attack began as early as

1453. Immediately after the fall of Constantinople, Pope Nicholas V proclaimed

a crusade. The war against the Ottomans frequently emerged as a subject for

discussion at the imperial diets in Germany in 1454-1455, although no

definitive decision was made. Not surprisingly, Hungary was swept by a wave of

panic, and the diet that assembled in January 1454 at Buda consented to

large-scale measures in order to mobilise a national army. It proclaimed the

general levy of the nobility, and renewed the institution of the militia

portalis. Four cavalrymen and two archers were to be equipped by every 100

peasant holdings, a demand that surpassed all previous recruiting measures. But

the projected offensive never took place; all that happened was that in the

autumn of 1454 Hunyadi marched into Serbia at the head of a small army and

defeated the forces left behind by the sultan at Krusevac. Planning continued

in 1455 and the diet levied an extraordinary tax, but that was all that took

place. The cause of the anti-Ottoman war was given renewed impetus by the new

Pope, Calixtus III (1455-1458), who tried to mobilize the whole power of the

Church in order to launch a new crusade. Although the princes of Europe turned

a deaf ear to the Pope’s request, he nevertheless aroused enthusiasm among the

common people in several places. He received much help from the Franciscans,

who deployed the skills of their popular preachers in the service of the `holy

war’. As a result of their unremitting zeal, by the summer of 1456 a huge

crusading army, consisting mainly of Germans and Bohemians, had assembled in

the area around Vienna, ready to march against the `infidels’.

However, this host never confronted the sultan, who began

the siege of Belgrade on 4 July with an army which modern scholars have put at

60,000 to 70,000 men. Hunyadi, assisted by the Franciscan Giovanni da

Capestrano, had successfully organised the castle’s defence and had assembled a

significant army in the vicinity. In the region of 25-30,000 crusaders,

`peasants, craftsmen and poor people’, rallied to Hunyadi’s camp under the

influence of Capestrano’s impressive sermons.

One of Belgrade’s greatest advantages was its geographic

location at the confluence of the Danube and Sava rivers. Mehmet would

similarly take advantage of Belgrade’s position by sailing over 200 ships up

the Danube river with canons, supplies, siege weapons and equipment. The

Ottomans would even establish founderies in Serbia to build and manufacture

canons to support the siege. Legend has it that the bells of Constantinople

were melted and used to manufacture the canons used against Belgrade in 1456.

With the Ottoman forces firmly in control of the river at this stage, the

Ottomans blocked Belgrade off from the Danube with a chain of ships, moored

upstream of the castle, and began placing their heavy guns outside the western

walls of the fortress. The bombardment of the fortress would began in July.

Hunyadi however anticipated this tactical move by Mehmed’s forces, and devised

a cunning attack to retake control of the river.

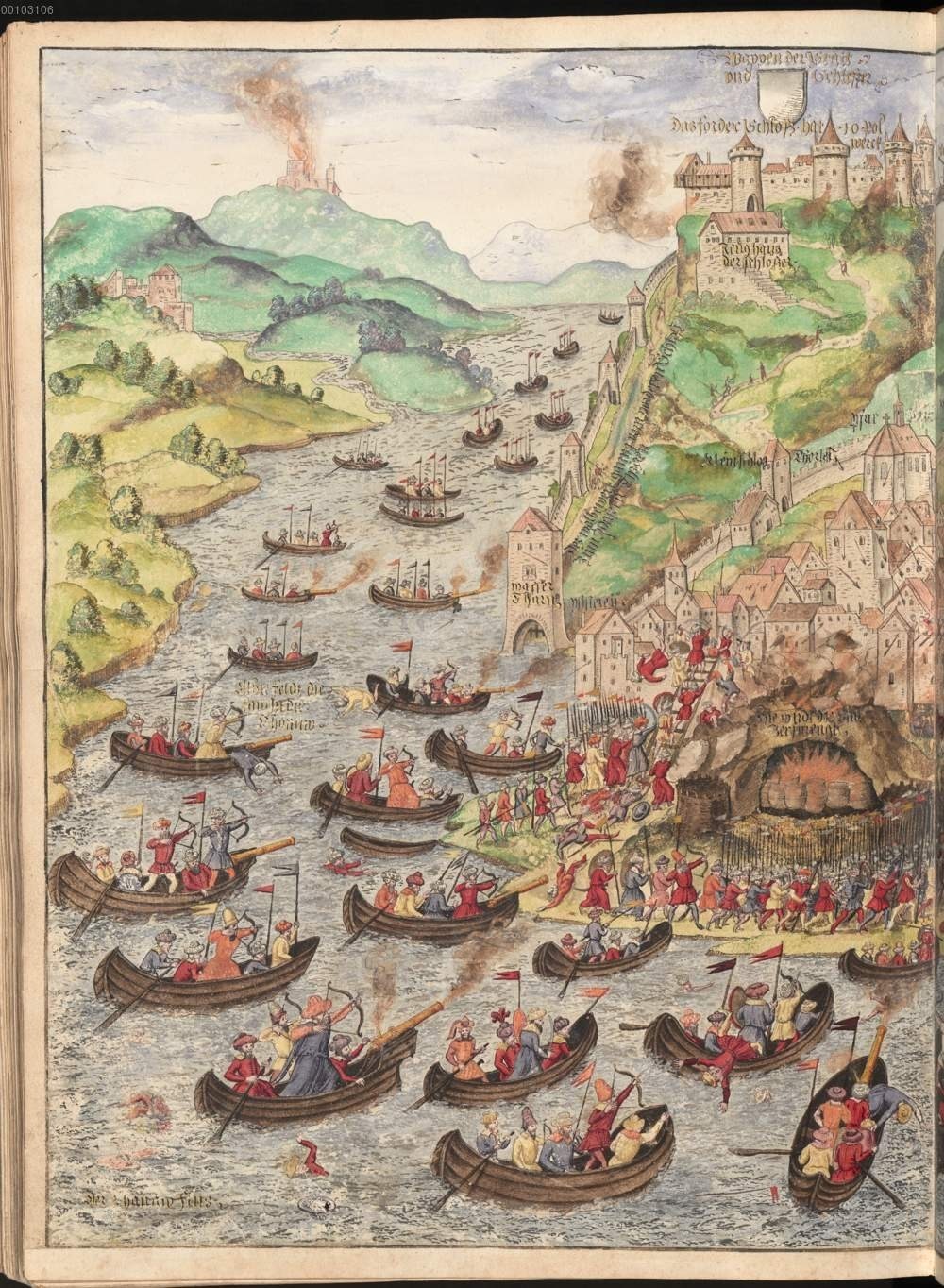

On July 13, 1456, a Hungarian fleet of vastly inferior

vessels broke the line of the Turkish fleet with the assistance of the fortress

commander, Mihaly Szilágyi. Both Hunyadi and Szilágyi (who was Hunyadi’s

brother-in-law), had river units that were anchored on the Sava River west of

Belgrade and further north on the Danube – and therefore out of reach by the

Ottoman forces. Both commander’s led a two-fronted attack against Mehmed II and

defeated the Ottoman river armada. With the defeat of the Ottoman fleet, the

Hungarians had control of the Danube again meaning the supply of needed

reinforcements to Belgrade could be provided uninhibited. Hunyadi could then

join his forces, camped about 30 kilometres north of Belgrade, with Szilágyi to

increase the defensive capability of the fortress.

The continued Ottoman siege against Belgrade proved

insufficient to deal a deciding blow to Hunyadi’s forces. Hunyadi was compelled

to lead a defensive fight due to the lack of enough calvary forces to attack

the Ottomans full-out. After almost ten days of unsuccessful sieges, on July

21, 1456 Mehmed ordered a full attack on the fortress. By the night of July 21

so many Ottoman attackers had been killed that chaos broke out among Mehmed’s

ranks. The next morning (July 22, 1456) Hunyadi rode out of the stronghold with

a small contingent and entered into hand to hand fighting with Medmed’s tired

and beleaguered army. The Sultan sent 6,000 fresh troops into combat, but these

troops could not defeat Hunyadi. Mehmed’s army experienced casualties in excess

of 50,000 men and, after the Sultan himself became wounded in battle, ordered a

general retreat to Sofia in Bulgaria.

The sultan withdrew with the remnants of his army and with

memories that prevented him and his successors from launching an attack of the

same dimensions for 65 years. News of this resounding victory soon reached the

West. The day on which the Pope received the news, 6 August, the day of the

Lord’s Transfiguration, was declared a general feast throughout the Christian

world. He had previously ordered that all the bells should be rung at noon to

encourage the soldiers, but his bull was not published until after the battle,

and thus the tradition, which continues in Hungary to this day, is generally

thought to be commemorative of the victory itself.

The victory presented an excellent opportunity for a

counter-attack, especially in view of the fact that considerable forces were

gathering in the heart of Hungary. But no offensive took place, because the

crusaders were already on the edge of open revolt. Anger against the

`powerful’, who had kept themselves far from the battle, had already been

growing during the fighting. Agitation became so intense after the victory that

Hunyadi and Capestrano decided to disband the army. Both of them soon died,

however. On 11 August, Hunyadi fell victim to the plague that had broken out in

the crusaders’ camp, and Capestrano followed him to the grave on 23 October.

Hunyadi was succeeded by his elder son, the 23 year-old

Ladislaus. He seems to have inherited his father’s ambition and slyness, but

apparently not his talent. Within a couple of days he found himself in conflict

with the king and Cilli, who demanded that the castles and revenues that had

been held by Hunyadi should be handed over. Cilli had himself appointed captain

general of the realm. Together with the king, and at the head of the foreign

crusaders who had recently arrived, he marched southwards with the aim of

taking possession of Belgrade and the other stipulated fortresses. To preserve

his position, the young Hunyadi decided upon an extremely hazardous course of

action. At the assembly of Futog he feigned submission and then enticed his

opponents into the castle of Belgrade. There, on 9 November 1456, he had Ulrich

murdered by his henchmen, and made himself master of the king’s person. Hunyadi

had himself appointed captain general, then took the king to Timisoara. Before

being set free, the king was made to swear that the death of Count Cilli would

never be avenged.

Ladislaus Hunyadi seems to have seriously miscalculated the

possible consequences of his actions. The unprecedented murder turned everyone

but his most determined followers against him: not only John Hunyadi’s enemies,

like Garai, but also his friends and supporters, like Ujlaki and Orszag, agreed

that Ladislaus should be bridled. Paying for perfidy with perfidy, they soon

made their opponent believe that he had nothing to fear; and the king too

showed himself a master of deception. On 14 March 1457, when Ladislaus was

staying at Buda with his brother Matthias, both were arrested, together with

their supporters. The royal council, functioning now in its capacity as supreme

court, convicted the Hunyadi brothers of high treason, and on 16 March

Ladislaus was beheaded in St George’s square in Buda. His supporters were

pardoned, but Matthias was held by the king, who immediately left Hungary for

Bohemia. The retaliation failed to bring about the desired consolidation,

however. Hunyadi’s partisans, in possession of his family’s immense and still

intact resources, reacted with open revolt. It was led by Matthias’s mother,

Elisabeth Szilagyi, together with her brother, Michael, while the royal troops

were commanded by Ujlaki and Jiskra. Fierce but indecisive fighting continued

for months, and was ended only by the news of Ladislaus V’s premature death in

Prague on 23 November 1457. Since the king had no lawful heir, the kingdom was

once again left without a ruler.