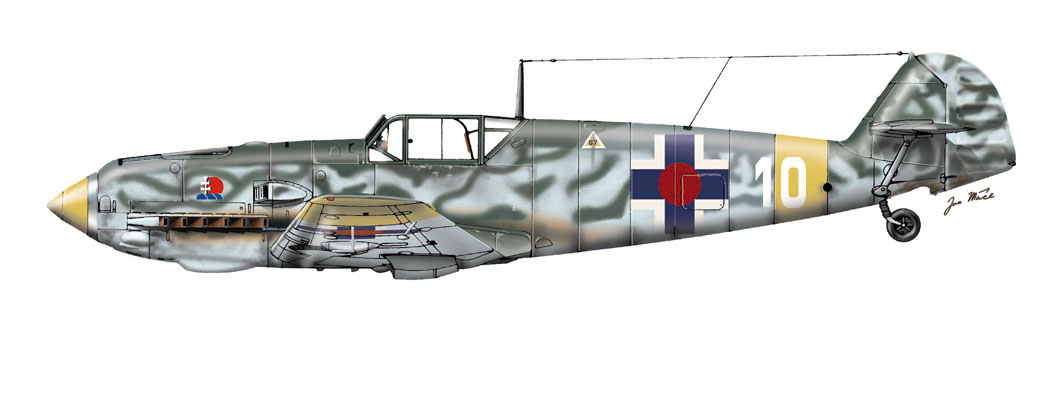

Messerschmitt Bf.109E-4 Unit: 13.Letka Eastern Front, December 1942.

Heinkel He.111H-10 Unit: 51.Dopravni letka Tri Duby, Slovakia, July

1943.

Praga E-39G The E-39G taking part in Training Courses of SVZ (Slovenske

Vzdusne Zbrane = Slovak Air Forces) based in Piestany in 1941. Note the yellow

painted fuselage bow and the yellow fuselage band in the same colour.

Messerschmitt Bf.109G-6/R3 Unit: 13 Letka Serial: 7 (W.Nr.161742) June

1944.

As some measure of the intense struggle for Kuban airspace,

13 (slow)IJG 52 doubled its total number of “kills” in little more

than a month. Aviation historian Rajlich writes that two pilots often managed

“to destroy as many as four aircraft each in a single day”6 They cite

the redoubtable Gerthofer, who shot down a pair of Lavochkins, one Shturmovik,

and a U.S. Boston medium-bomber, all on April 24. Five days later, four Yak-1

fighters fell one after the other under the guns of rotnik (staff sergeant) Izidor

Kovarik. These achievements were widely publicized back home, where the crews

were popularly revered as “the Tatra Eagles;’ after the high mountain

range bordering Poland.

Continuous Slovak and German air victories resulted in

unacceptable losses for the Soviets, who gradually relinquished their bid for

the Kuban, and the focal point of the Eastern Front gradually shifted away

toward a confluence of the Kur, Tuskar, and Seym Rivers around the city of

Kursk. As history’s greatest tank battle got under way there on July 4, a

Petlyakov bomber burst into flames under the accurate marksmanship of

nadporucik (first lieutenant) Vladimir Krisko. It was not only his ninth and

last success, but the final victory won by13 (slow)/ JG 52’s first team

members, who were sent home after a grueling eight months of combat. They were

relieved by crews whose average age was just 24 years old, although each pilot

benefited from more extensive training.

Their preparation was soon apparent in the 48 enemy aircraft

that fell under their guns during the first 12 weeks of engagement. Moreover,

the Soviets’ venerable Polikarpovs and Yaks were being replaced by American

Aircobras and British Spitfires, which could match the Messerschmitt-109 in

many particulars. It was especially to their credit then, that the airmen of 13

(slow)IJG 52 could celebrate their 2,000th combat mission on August 28. In

October, they moved to Bagerovo airfield, west of Kerch, where its strait

connects the Black Sea with the Sea of Azov, an area soon to be hotly contested

between the Wehrmacht and the Red Army.

But the Slovaks were more concerned for the immediate

protection of their homeland, which had recently come within striking

capabilities of long-range U.S. heavy-bombers after Allied forces occupied

airfields along the eastern Italian peninsula. Goering gave the Tatra Eagles

leave to dissolve 13 (slow)IJG 52 and return home, but not before a Lavochkin

La-5 fighter fell into the Kerch Channel under the guns of rotnik Frantisek

Hanovec, as a parting shot at the Soviets, and the last Slovak aerial victory

on the Eastern Front.

Since August 1941, the Slovaks accounted for 221 confirmed,

plus 29 unconfirmed “kills;’ in more than 2,600 sorties. These numbers are

aside from very many ground attack, anti-partisan, reconnaissance, and escort

duties additionally undertaken during some 16 months of combat. Their

achievement seems particularly remarkable when we learn that it was

accomplished by less than 100 pilots, only 4 of whom were killed. Seventeen

became aces, shooting down at least five enemies each. Such statistics speak to

the high skill and determination of the Slovak airmen, who usually fought

against opponents that not only outnumbered them, but flew warplanes, which,

later in the war, technologically matched their own.

As the Slovak veterans returned to their country, however,

they found conditions changed, and not for the better. During the previous two

years, Soviet intelligence had waged a concerted campaign to infiltrate

Slovakia with numerous covert operatives, who prepared the ground for revolt.

They found the general population, and especially the peasantry, still

favorably disposed to the Tiso regime, but made important allies among urban

residents and the aristocracy, which in large measure controlled the nation’s

armed forces. Importantly assisting the agents was Germany’s deteriorating

military situation, which certain SVZ commanders hoped to use for disengaging

Slovakia from the war.

Meanwhile, the former 13 (slow)IJG 52 crews were formed into

a new unit, the “Readiness Squadron;’ for homeland defense on January 31,

1944. It began with shining hopes for the future, and among the brightest was

its outstanding pilot, zastavnik (master sergeant) Izidor Kovarik, the nation’s

second-highest-scoring ace with 28 confirmed kills. In April, he transferred as

an instructor at the Tri Duby flying school, where he and his student died the

following July 11 in the crash of his Gotha Go 145 biplane trainer after the

structural failure of its upper wing. His loss was a terrible blow to the

entire SVZ and particularly to his comrades in the Readiness Squadron.

Their 11, aging Emils and three Avias were almost hopelessly

inadequate as interceptors, so Goering rushed 15 new Messerschmitt Me109G-6s

straight from their Regensburg factory to Piestany, plus the first of some 25

Stukas. A trio of Junker Ju-87Ds arrived in time for the Soviet spring

offensive against the Carpathian Mountains at the country’s eastern border. The

SVZ-flown Doras operated with three more Letov bombers out of Spisska Nova Ves

in numerous ground-attacks on the advancing Red Army.

In June, a dozen more dive-bombers were received-mostly

older B and D models (some unarmed for use as trainers)-plus five,

factory-fresh D-5s. A final 11 Doras arrived from Germany the following August.

But as the U.S. bomber streams overflew Slovakia, they went unopposed by

Readiness Squadron fighter pilots, who stayed well beyond firing range. They

were under secret orders by the treasonous Minister of National Defense (!) and

Chief of Staff of Land Forces to save themselves for an anti-German

insurrection in the making. A few commanding officers were briefed of these

plans; most pilots were not, but nonetheless forced to obey orders. Their

passive resistance to the enemy came to a head on June 16, when Bratislava was attacked

by Boeing B-17 Flying Fortresses and Consolidated B-24 Liberators for the first

time. The capital city suffered extensive damage, and 717 men, women, and

children were killed, with another 592 injured.

The Readiness Squadron pilots in their new Messerschmitts

had been eye-witnessed by too many civilians circling far out of harm’s way. A

pair of bombers destroyed by loyal anti-aircraft gunners were the only

intruders shot down. Popular reaction was outraged, with loud denunciations of

disloyalty hurled at the airmen. Luftwaffe observers condemned them as cowards.

Stung by these accusations, Deputy CO nadporucik Juraj Puskar ignored the

orders of his scheming superiors to lead a full-scale attack against the next

American bomber formation 10 days after the Bratislava raid. In what was to be

the greatest Axis aerial opposition over Slovakia, 203 Luftwaffe interceptors

were joined by 30 Hungarian fighters and 8 Tatra Eagles.

They arose to confront more than 500 Flying Fortresses and

Liberators protected by 290 P-38 Lightnings and P-51 Mustangs on their way to

strike oil refineries and depots in the vicinity of Vienna. Puskar and his

pilots dove into the air armada, but only rotnik Gustav Lang broke through its

ring of escorts to fire on a single B-24 that crashed at Most na Ostrove. His

Messerschmitt was immediately thereafter riddled with .50-caliber rounds fired

by USAAF fighters. Three of his remaining seven comrades were killed in short

order by overwhelming numbers of the enemy, another was gravely wounded, and

all their aircraft gunned down. The Readiness Squadron had been shattered.

In late August 1944, armed forces’ plotters made their move

to overturn the Tiso regime and expel German forces from Slovakia. Their

action, according to Milan S. Durica, Slovakia’s leading historian, was less

the “national uprising” portrayed by postwar Communist propaganda and

picked up by uncritical scholars in the West, than a collection of criminals

armed and organized by Soviet agents.’ In any case, after two months of chaos

during which Slovakian peasants were predominantly the defenseless victims of

murder and looting, it petered out, as much for lack of popular support, as for

the intervention of Wehrmacht troops, who were more often than not welcomed and

aided by the rural populace in hunting down the bandits. The revolt was chiefly

notable for one of the few combat successes achieved by the insurgents, when an

Avia flown by Frantisek Cyprich shot down a German Junkers Ju-52 transport

plane with Hungarian markings on September 2. The elderly trimotor was unarmed,

its crew unaware that any “national uprising” had taken place.

Earlier, on February 15, 1942, President Tiso’s Ministry of

Defense began organizing and recruiting for an airborne infantry aimed at striking

important targets not otherwise accessible deep behind enemy lines. These would

include Red Army headquarters, fuel and ammunition depots, and railway centers.

By October, the first volunteers had been selected for the Junior Air Cadets’

School at Trencianske Biskupice, commanded by 1st Lieutenant Juraj Mesko. His

men were trained as infantry sappers in close-quarter combat, sabotage,

demolitions, and field communications.

The pace of their instruction was slowed by lack of

sufficient aircraft and basic supplies, due to exigencies of the Eastern Front.

But June 12, 1943, Mesko and three top-scoring classmates-Jozef Lachky,

Ladislav Lenart, and Jozef Pisarcik-were provided officer training at the

Deutsche Fallshirmjagerschule II (German Paratrooper School-II), in

Wittstock-Dosse, 60 miles northwest of Berlin. There, they were familiarized

with equipment and tactics and learned the Fallschirmjager’s Ten Commandments:

1. You are the elite of the Wehrmacht. For you, combat shall

be fulfillment.

2. You shall seek it out and train yourself to stand any

test.

3. Cultivate true comradeship, for together with your

comrades you will triumph or die.

4. Be shy of speech and incorruptible. Men act, women

chatter. Chatter will bring you to the grave. Calm and caution, vigor and

determination, valor and a fanatical offensive spirit will make you superior in

attack.

5. In facing the foe, ammunition is the most precious thing.

He who shoots uselessly, merely to reassure himself, is a man without guts. He

is a weakling and does not deserve the title of paratrooper.

6. Never surrender. Your honor lies in Victory or Death.

7. Only with good weapons can you have success. So look

after them on the principle: First my weapons, then myself.

8. You must grasp the full meaning of an operation, so that,

should your leader fall by the way, you can carry it out with coolness and

caution.

9. Fight chivalrously against an honest foe; armed

irregulars deserve no quarter.

10. Keep your eyes wide open. Tune yourself to the top-most

pitch. Be nimble as a greyhound, as tough as leather, as hard as Krupp steel,

and so you shall be the Aryan warrior incarnate.’

After two months at Wittstock-Dosse, the young Slovaks

returned to their homeland and a new school in Banska Bystrica, at the Tri Duby

airport. The 34 cadets underwent intensive instruction, making their public

debut on October 30, when they jumped for the first time en masse from a pair

of German aircraft before President Tiso near the town of Zilina. The right

side of their helmets were then hand-painted (not decaled) with Slovakia’s

airpower insignia: a white patriarchal cross standing above three, blue hills

with a red sun rising in the background, the same emblem applied to engine

cowlings of aircraft operated by Slovak crews. The sleeve of their dress

uniform featured the image of a deployed chute on a blue patch encircled by a

white band.

During January 1944, the paratroopers pursued advanced

training, including night-time jumps-the first exercises of their kind in

military history, not even attempted by the German Fallschirmjagern. In

February, winter instruction took place near the village of Lieskovec. Before spring,

the unit experienced an influx of new members, so much so, they passed abreast

in review during Bratislava’s annual Armed Forces’ Day parade on March 14.

However, development had been hindered since the group’s inception by a dearth

of supplies and aircraft, virtually all of it eventually provided by Germany.

Short on supplies themselves, the Fallschirmjagern spared

what chutes, jump smocks, and helmets they could, and Goering dispatched

several medium-bombers modified to accommodate 16, fully equipped airborne

soldiers each. These were examples of the Heinkel He.111K-20/ R1, among the

last production variants of this famous warplane, having entered service when

the Slovaks were in need of just such an aircraft. Its spacious, ventral hatch

facilitated rapid jumps, and FuBI 2H blindlanding equipment aided night

operations in which the paratroopers specialized.

When the “national uprising” erupted in August,

some 80 Slovak paratroopers located at Banska Bystrica warded off all attacks

on the Tri Duby airport. They and the rest of their comrades later participated

in fierce fighting along the Zvolen-Kremnica railway and around the villages of

Gajdel, Jasenovo, and Svaty Kriz. A few of Lieutenant Mesko’s men deserted;

one, captured by the Germans, was executed, while another, severely wounded,

was killed when the truck in which he was being driven to a prisoner-of-war

camp infirmary was strafed by USAAF fighters.

After the insurgency was put down, Slovak paratroopers

continued to engage the invading Soviets, but with the loss of every Heinkel

and no prospect for re-supply, plus the seizure of most airfields by the enemy,

their unit’s further existence as an airborne organization was no longer

justified, and they disbanded in mid-November.

Although some SVZ pilots, for various reasons, joined the

insurgency, Slovakia’s most successful airmen did not. Jan Reznak, his

country’s leading ace with 32 confirmed and 3 unconfirmed “kills;’ refused

to switch sides. His comrade and friend, Jan Gerthofer (26 “kills”),

even though imprisoned by the Germans at Austria’s Stalag XVIIA prisoner-of-war

camp, until his release in February 1945, likewise remained loyal to the Tiso

regime.

After the war, both men enlisted in the newly reconstituted

Czechoslovak Air Force as flight instructors. But their past eventually caught

up with them. In 1948, Reznak was discharged for his “negative attitude

toward the People’s Democracy”‘ Three years later, he was grounded

permanently, when his pilot’s license was confiscated by the State Security

Police. By 1951, Gerthofer had become a civil transport pilot, but in June he,

too, was forbidden to fly for political reasons, and the highscoring ace was

forced to work as a manual laborer.

Critics of Prime Minister Tiso fault him for bringing his

country into World War II against even Adolf Hitler’s early advice. Yet,

neutrality would not have spared Slovakia from the Red Army that overran all of

Eastern Europe in 1945. So too, the Slovakian Air Force could not, alone,

fundamentally influence the course of events, due to its numerical

disadvantage. Yet, the achievement of its crews was all out of proportion to

its relatively small size, and they did, after all, significantly contribute to

events on the Eastern Front. As such, they secured an especially high position

for gallantry in the history of military aviation.