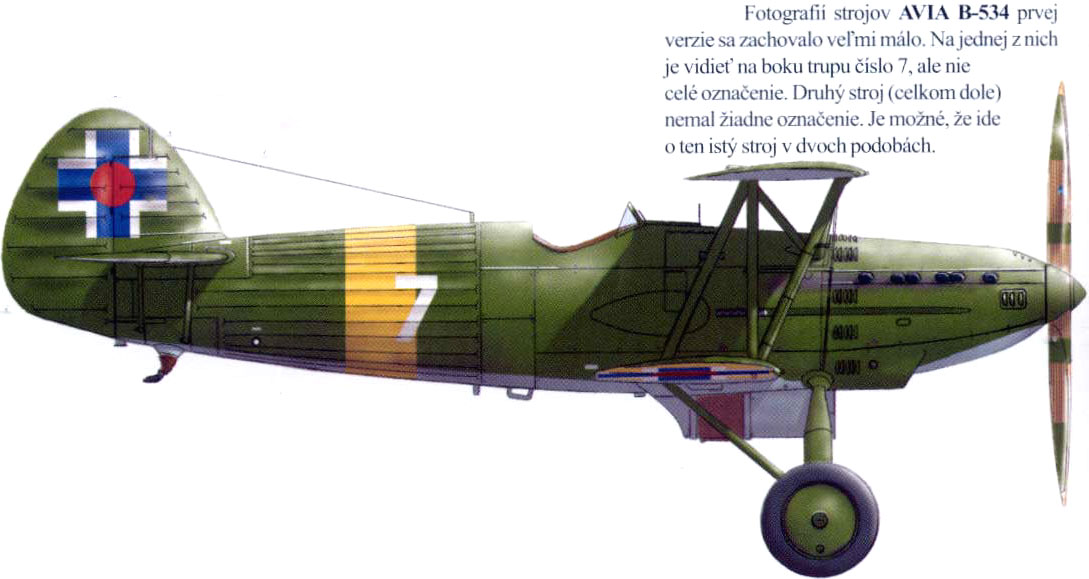

Avia B.534-I There exist only a few photos of B.534-I series. On one of

them we can see this B-534 with number 7 on the fuselage, but this marking is

not complete.

Letov S-328 of rising air force during Slovak National Rising (against Germans in 1944). Czechoslovak national insignia, completed with silhouettes of three mountains with Slovak cross.

The 2.8 million Sudeten Germans freed by Czechoslovakia’s

disintegration, beginning in September 1938, triggered the liberation of other

minorities stranded for nearly 20 years behind the borders of that artificial

state. Teschen, with its predominantly Polish population, went back to Poland;

and Hungarians in Ruthenia, at Czechoslovakia’s extreme eastern section,

declared independence on March 14,1939. During the afternoon of that same day,

the Slovak people proclaimed their own state, which the Romanian government in

Budapest officially recognized 24 hours later.

The Hungarians were likewise determined to reclaim the rest of their fellow countrymen, who made up a majority population in northeastern Slovakia, where they had been stranded since passage of the Versailles Treaty following World War I. On March 23, Honvedseg troops stormed across a border as ill-defined as it was ill-defended. Unprepared troops of the Slovak Army were routed, then rallied, but were ultimately unable to contain the invaders. Hardly less auspicious was the fledgling Slovenske vzdušné zbrane, the Slovak Air Force, really nothing more than the former 3rd Czech Air Regiment. Although the Letecky pluk 3 still possessed 230 aircraft, there were only 80 pilots and observers to man them.

They nonetheless seized the initiative on the opening day of

hostilities, when their open-cockpit biplanes struck the Hungarian-occupied

cities of Mukacheve, Roznava, and Uzhorod. One of the Letov bombers was brought

down by flak, which additionally destroyed two fighters and inflicted damage on

four more, plus another bomber. Undaunted, the Slovaks returned 24 hours later

for their first aerial combat. They flew the Czech-designed and -manufactured

Avia B-534, among the last of the great biplane fighters, such as Britain’s

Gloster Gladiator, Italy’s Falco, and Russia’s Chaika.

Powered by an 850-hp Hispano-Suiza HS 12Y drs 112-cylinder,

Vee piston engine, the Avia could achieve a maximum speed of 245 mph at 12,435

feet, with a service ceiling of 34,775 feet, and a 360mile range. These

qualities won laurels for the rugged aircraft at 1937’s International Flying

Meet in Zurich, where it proved at least equal to all competition and

out-performed Germany’s own biplane fighter, the Heinkel-51. The B-534 was not

envisioned strictly as a fighter, however, and made to serve a ground-attack

role. As such, four Model 30, 7.92-mm machine-guns installed in the sides of

the fuselage were synchronized to fire through the propeller, or, alternately

(as the Bk 534), a single, 20-mm cannon firing from the nose was supplemented

by a pair of 7.92-mm machine-guns at the sides. Provision was also made for six

44-pound bombs. It was in this mode that three Avias tangled with an equal

number of Hungarian-flown Italian fighters in the early morning of March 23.

The Avia owned a 12-mph speed advantage over the Fiat CR.32, but better-trained Magyar Legier pilots prevailed. The 264-pound payload aboard CO podporučík (second lieutenant) Jan Prhacek’s aircraft was hit and exploded, atomizing his aircraft and killing him instantly, but desiatnik (corporal) Cyril Martis dropped his bombs before crash-landing upside down in a swamp. With the sudden loss of his commanding officer and comrade, and faced by three-to-one odds, slobodnik (lance corporal) Michal Karas out-maneuvered his opponents, escaping unscathed to the base at Spisska Nova Ves. Shortly after his escape, two of three Avias attempting to attack enemy tanks advancing on Tibava a Sobrance were brought down by ground-fire.

Three more B-534s returned to the same general area escorting a trio of Letovs, but were met this time by nine Fiats. Although the observer, podporučík Ferdinand Svento, parachuted from a bomber falling in flames, his body was riddled with 18 rounds of machine-gun fire, as he hung helpless in his harness. Another Letov was shot down outside the village of Strazske, but one survived the carnage to return to base. All three Avias were destroyed without cost to the Hungarians. Later that same day, 10 Junkers Ju. 86K-2 bombers purchased by the Hungarians from Germany before the advent of hostilities struck Spisska Nova Ves in the first raid of its kind on Slovakian soil. A dozen soldiers and civilians perished, with almost 100 injured, but the base did not suffer crippling damage.

A flight of seven Avias attempted retaliation by diving on advancing enemy troop concentrations in the vicinity of Paloc, but nine defending Fiat CR.32s claimed all the Slovak fighters at no loss to themselves. By then, the Hungarians had achieved limited objectives on the ground and sued for peace. In what the Slovaks referred to as Mali Vojn, “The Little War,” they lost 58 dead (22 soldiers and 36 civilians) against 23 Hungarian fatalities (8 soldiers and 15 civilians) during a week and a day of fighting. They were determined to learn from this premature baptism of fire, however, and initiated a serious reorganization of their armed forces, with special attention given to pilot training in the SVZ.

The Slovaks inherited a broad variety of aircraft from the

Czechs, but many were worn out or hopelessly obsolete. These were either

scrapped or consigned to student pilot squadrons, while frontline machines were

refurbished almost entirely by innovative mechanics, because Slovakia did not

possess a modern aviation industry. The already small SVZ was downsized still

further, but its organizational structure tightened up, and a parachute brigade

established. Just five months after the conclusion of the Little War, the

Slovakian Air Force was a noticeably improved, although far from perfected

service, when a much larger war broke out on September 1, 1939.

Joining Hitler’s Blitzkrieg against Poland were 35,000

Slovak troops set in motion by their Prime Minister, Jozef Tiso. Their limited

objectives were recovery of original Slovak territories in Javorina, Orava, and

Spis seized by the Poles during 1920, 1924, and 1938. Slovak participation in

the Campaign was not entirely self-serving, however, because Tiso was himself a

convinced Fascist and trusted friend of the Germans. They had informed him of

the up-coming invasion as early as August 28, when he arranged for part of the

their attack to be launched from Slovak areas bordering Poland. Beyond the

recapture of former regions, he put his air force at the disposal of the

Wehrmacht.

To the SVZ warplanes’ national insignia (a red disc with blue twin-cross outlined in white) were added black-and-white Luftwaffe Balkenkreuzen (“Balkan Crosses;’ Iron Crosses) on either side of fuselages and wing surfaces. Tiso dispatched 20 Letov S.328s and as many Avias to scout for his advancing troops, but even after they took Javorina, Orava, and Spis, the fighters stayed on in Poland to escort German Stukas dive-bombing enemy railroad yards around Drogobytch and Lvov. During one of these attacks, on September 9, anti-aircraft fire brought down an Avia flown by čatár (sergeant) Viliam Grun. He was captured and became a prisoner of war, but shortly thereafter made good his escape to rejoin his unit, Number 12 Squadron.

Three days earlier, a lone, unidentified aircraft flew over military installations inside Slovakia. A trio of Avias scrambled to investigate and intercepted a Lublin R-XIII (not a RWD-XVII aerobatic trainer, as sometimes reported),’ the Polish Army’s standard liaison-spotter. Forty-nine of the Polish parasol observation and liaison planes had been organized into eskadra obserwacyjna, or special observation squadrons, for long-range photographic missions. The Lublin was a versatile workhorse. Its tough construction and remarkably short takeoff run of just 204 feet were likewise ideally suited to field operations of all kinds, including courier and ambulance duties.

One R-XIII had tried to attack an enemy vessel on when the

elderly Schleswig-Holstein-a pre-dreadnought battleship from 1908-was

mercilessly pounding Polish defenders at Danzig with an unremitting, hours-long

fusillade of 11-inch shells fired at virtually point-blank range. Unable to

find his target, the pilot dropped a stick of 55-pound bombs on a German

residential neighborhood instead. But a single 7.7.-mm Lewis machine-gun

operated by the observer was inadequate defense against the three Avias, which

handily shot down the reconnaissance plane in flames. Its destruction signified

the young SVZ’s only kill of the Campaign and its first-ever aerial victory.

These were not the only Slovakian warplanes operating over

Poland, however. When the brunt of Luftwaffe aircraft was thrown into the siege

of Warsaw, and Wehrmacht ground forces in the south suddenly lost their eyes in

the sky, the Slovaks volunteered their open cockpit, two-place biplanes. The

Czech-built Hispano-Suiza Vr-36 engine could only provide 740 hp for a maximum

speed of 170 mph, but when the Aero A.100 was not shooting photographs of enemy

troop movements, it fired four 7.92-mm wz.29 machine-guns or dropped 1,300

pounds of bombs, thereby offering German ground forces much-needed air cover

they would have otherwise missed.

The territories Tiso’s soldiers reclaimed during 1939s

conquest of Poland more than compensated for regional losses to the Hungarians

earlier that year and brought closer ties with the Third Reich. Yet, less than

two years later, Hitler did not include the Slovaks in his original plan to

invade the USSR, and even tried to dissuade them from participating, because he

believed too many of Tiso’s people would side with their fellow Slavs in

Russia. But the President argued persuasively on behalf of his fellow

countrymen’s loyalty, and Slovakia was eventually allowed to join Germany’s

other allies in their combined assault on the citadel of Communism.

However, he was disappointed to learn from the SVZ commander

in chief, General Anton Pulanich, that just 33 Avias and 30 Letovs were in

fully operable condition. Moreover, they could only be fueled with a unique

alcohol-benzene-gasoline mixture not employed by any other aircraft on the

Eastern Front. Supplies of this singular concoction needed to be constantly

brought up from Slovakia, a process made increasingly difficult, as operations

moved further away into the East. Despite these drawbacks, three fighter

squadrons (the 11th, 12th, and 13th Letky) joined as many bomber-reconnaissance

squadrons (the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd Letky) in western Ukraine by July 7, 1941.

Only then did General Pulanich realize that the homeland had

been left without enough interceptors to defend against attack and re-assigned

the 11th Letky to Piestany. His already small armada was now down to only 20

fighters. These were inadequately supplemented by 10 former Czech elementary

trainers pressed into service for reconnaissance duties, for which the Praga

E-39-with its 150-hp, nine-cylinder Walter Gemma, air-cooled, radial engine-had

never been designed.

With a top peed of just 106 mph, the rugged little biplanes were surprisingly effective, flying cover and observation for Slovakian ground forces in the conquest of Lvov, Kiev, and Rostov. Fortunately for the defenseless Pragas, skies above these cities had already been mostly swept clear of Soviet machines by the Luftwaffe, making aerial combat unlikely. But Red Army anti-aircraft fire remained dangerous, and čatár Frantisek Brezina’s Avia B-534 was the first Slovak to fall to Russian flak on July 25, while in the act of flying escort for a German Henschel Hs.126 observation plane.

Forced into an emergency landing far behind enemy lines, he came under fire from approaching troops. These were strafed by his squadron comrade, čatár Stefan Martis, who then landed as close as possible to Brezina, enabling him to jump aboard the lower, port wing. More Russian soldiers fired on the Avia, as it took off with the rescued pilot clinging to a strut for dear life. Although Martis was shot in the leg and his fuel tank holed by gunfire, he managed to safely reach the SVZ airfield at Tulczyn with a badly wind-blown, but otherwise sound Brezina.

The incident was important, because it for the first time

won the favorable attention of Luftwaffe brass, who awarded Martis the Iron

Cross Second Class, in addition to the Silver Medal for Heroism he received

from his own country. When, merely five days later, another downed flyer was

rescued in an identical fashion by a SVZ pilot, Slovak courage featured

prominently in the German press.

Still, more than a month was to pass before General

Pulanich’s airmen finally confronted the Red Army Air Force on July 29, with

inconclusive results, neither side claiming any “kills:” In August,

however, fighters of the 12th Letky destroyed three Polikarpov I-16s near Kiev

without loss to themselves. While these numbers are not high, the Slovak

achievement was nonetheless significant, because the Soviets’ low-wing

monoplane Rata was more than 80 mph faster than the Avia double-deckers.

The fighting around Kiev spilled into early September, when

10 B234s attacked 9 of the markedly superior Polikarpovs, shooting down two of

them without suffering casualties. A third Rata was destroyed 24 hours later,

during a patrol of three Avias above the Dniepr bridge. While no Slovaks had

been killed yet on the Eastern Front, their equipment was so badly worn out,

continued operations were no longer feasible, and all squadrons were reassigned

to the homeland before the close of 1941. Thus ended the purely Slovakian phase

of the SVZ’s involvement in World War II. But Hermann Goering had been

impressed by these doughty crews, winning victories with patently obsolete

aircraft, and offered to provide them pilot instruction for an all-Slovak

squadron. Designated 13 (slow)/JG 52, it would be attached to a Luftwaffe unit

(II. JG 52) with its own Messerschmitt-109s.

Accordingly, 19 Slovakian students arrived at Karup airfield

in occupied Denmark on February 25, 1942, to complete their conversion training

some four months later, when they were transferred on behalf of advanced combat

instruction in Piestany. They finally left during October for their new

operational base at Maikop, where they awaited the arrival of their fighters.

The aircraft were something of a disappointment: outdated Messerschmitt-109Es,

scarred veterans of the Battle of Britain. Some, in fact, were repaired crash

victims. Undeterred, the Slovaks were committed to proving themselves and

dressed their seasoned Emits in the new national insignia of a dark blue cross

outlined in white with a red disc at the center.

On November 29, just two 13 (slow)IJG 52 Messerschmitts took

on nine Polikarpov Chaikas, shooting down three of them, suffering no losses of

their own. During the weeks that followed, the Slovaks escorted Luftwaffe

Junkers-88 and Heinkel-111 bombers, and undertook ground attacks against enemy

transportation. They were rewarded by Goering in mid-December when he replaced

their used-up Emits with the much-improved Messerschmitt Me-109F-4. The Slovak

pilots immediately took to this more up-to-date model, as evidenced by their

escalating number of kills. The Friedrichs came just in time, because the

Soviets were replacing their out-moded Chaikas and Ratas with far better Yaks,

Migs, and Lavochkins. It was at the controls of 109Fs that the first Slovakian

aces began to make their impact on the Eastern Front during early 1943.

While flying Avia biplanes, they were fortunate to get a

crack at the enemy. Now, pilots such as Jan Reznak, Jan Gerthofer, and Jozef

Jancovic were competing among themselves for the position of Top Gun. As

testimony to the desperate measures undertaken by Red flyers to destroy their

Slovak opponents, Jancovic returned to base after a memorable encounter on

January 20, when a Polikarpov 1-16 left part of its wing embedded in his own

aircraft! The Rata pilot had attempted to ram Jancovic head on.

A rapidly growing tally of successful sorties collected by the Slovaks yet again caught Hermann Goering’s eye, and he re-equipped their squadron with the latest Messerschmitt Me-109G-4s. These state-of-the-art warplanes and their crews were soon put to the test when they were moved from Maikop to an airfield on the Taman Peninsula. According to CO stotnik (captain) Jozef Palenicek, “In the sector to which the squadron has been assigned, enemy air activity has increased to such an extent that pilots-mainly on escort flights-have to engage with forces up to nine times more numerous”‘

The Red Army Air Force mounted a maximum effort for undisputed ascendancy over the Kuban, a region of southern Russia surrounding the Kuban River on the Black Sea between the Don Steppe, Volga Delta, and Caucasus. It was here that Stavka, the Soviet high command, intended to break the Axis on the Eastern Front. Never before had the Slovak airmen been caught up in such ferocious and relentless engagements, which intensified throughout March, when one of their leading aces, čatár “Jozo” Jancovic, was killed. Reznak likened him to “a bird of prey, who never took any account of his own safety in air combat;’ a recklessness that prevented him from noticing a Lavochkin interceptor while attacking Shturmovik bombers.’ Although pulled from his crashed landing, Jancovic died of his injuries soon after at a Zaporoshskaya field hospital.

He had at least lived long enough to celebrate his squadron’s 50th confirmed victory on March 21, when podporučík Gerthofer splashed a Petlyakov Pe-2 into the Black Sea. This victory was also the first Peshka dive-bomber claimed by 13 a success that drew widespread congratulations, including a personal telegram from Reichsmarshal Goering. His chief of the air department at the Deutsche Luftwaffenmission in der Slowakei, Oberleutnant Ignacius Weh, reported after inspecting the Taman base, “the Slovak fighter squadron is delighted to fight:”