Launching a Maurice Farman two-seater from the Wakamiya during the

Siege of Tsingtau.

“Plüschow in front of the city wall of Haizhou in

the province of Jiangsu, on November 6, 1914. On that day he had escaped the

besieged Tsingtao by his plane, and after a flight of ca. 200 km to the

southwest, landed at Haizhou, because the plane had no fuel anymore.”

Both sides had elements of an air component; the Japanese

Navy had the Wakamiya Maru with its complement of four Maurice Farman

floatplanes, whilst the army detachment, initially consisting of three

machines, deployed from an improvised airstrip near Tsimo on 21 September.

Japanese aviation was, as was the case in every other nation, a recent

phenomenon in terms of powered aircraft. Previous interest in aeronautics had

centred on the use of balloons for reconnaissance, the first Japanese military

balloons were sent aloft in May 1877, and an advanced kite type was designed

and constructed in 1900 and successfully used during the Russo-Japanese War. A

joint committee, with army, navy and civil input, was created on 30 July 1909

to investigate and research the techniques and equipment associated with

ballooning; the Provisional Military Balloon Research Association or PMBRA.

Nominated by the Japanese Army to serve on the PMBRA were

two officers with the rank of captain, Tokugawa Yoshitoshi and Hino Kumazo.

Both had some experience with aviation. Hino designed and constructed a pusher

type monoplane with an 8hp engine that he unsuccessfully, the engine was

underpowered, attempted to get off the ground on 18 March 1910. Tokugawa was a

member of the balloon establishment during the Russo-Japanese War. Both were

sent to Europe in April 1910 to learn to fly at the Blériot Flying School at

Étampes, France. Having passed the rudimentary course, they purchased two

aeroplanes each and had them shipped to Japan; Tokugawa obtained a Farman III

and a Blériot XI-2bis in France whilst Hino purchased one of Hans Grade’s

machines and a Wright aircraft in Germany.

The first flights of powered aeroplanes in Japan occurred on

19 December 1910 at Yoyogi Park in Tokyo. Tokugawa flew the Farman III, powered

by a 50hp Gnome engine, for 3 minutes over a distance of some 3000m at a height

of 70m. Hino followed him immediately afterwards in the Grade machine, powered

by a 24hp Grade engine, which flew for just over a minute and covered a

distance of 1000m at a height of 20m.

A naval member of the PMBRA, Narahara Sanji, started on

designing and constructing an aeroplane, with a bamboo airframe and a 25hp

engine, during March 1910. Because of the low powered engine the machine failed

to lift off when this was attempted on 24 October 1910, but with a second

machine, the ‘Narahara Type 2’ powered by a Gnome engine similar to that used

in the Farman III, he managed a 60m flight at an altitude of 4m on 5 May 1911.

This flight, at Tokorozawa, in Saitama near Tokyo, the site of Japan’s first

airfield, is considered to be the first Japanese civilian flight as Narahara

had left the navy when he made it. It was also the first flight by a

Japanese-manufactured aeroplane.

The first military flight by a Japanese-manufactured machine

took place on 13 October 1911, when Tokugawa flew in a ‘PMBRA Type (Kaisiki) 1’

of his own design, based on the Farman III at Tokorozawa. These pioneers,

whilst they had made astonishing progress, did not however possess the

necessary research and technological resources to take Japanese aviation

further. Because of this the Japanese decided to import aviation technology

from Europe, though the navy established the Naval Aeronautical Research

Committee in 1912 to provide facilities to test and copy foreign aircraft and

train Japanese engineers in the necessary skills. Via this system, the

foundations of a Japanese aviation industry were being laid; in July 1913 a

naval Lieutenant, Nakajima Chikuhei, produced an improved version of the Farman

floatplane for naval use. Nakajima Aircraft Industries, founded in 1917 after

Nakajima resigned from the navy, went on to massive success.

The French were the world leaders in military aviation, with

260 aircraft in service by 1913, whilst the Russians had 100, Germany 48, the

UK 29, Italy 26 and Japan 14. The US deployed 6.55 It comes as no surprise then

to note that during the campaign against Tsingtau all the aeroplanes deployed

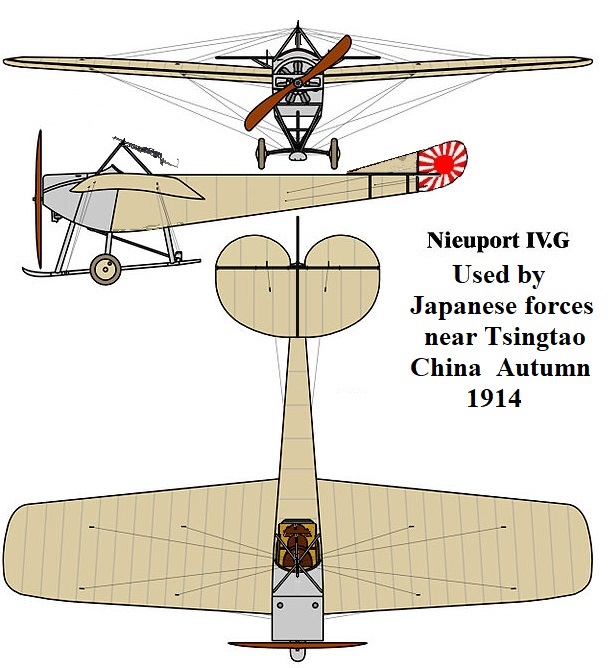

by both Japanese services were French. Four Maurice-Farman MF7 biplanes and one

Nieuport 6M monoplane formed the Army’s Provisional Air Corps, flying

eighty-six sorties between them, whilst the navy deployed one Maurice-Farman

MF7 floatplane and three Henri-Farman HF7 floatplanes. The navy planes flew 49

sorties and dropped 199 bombs.

A floatplane from the Wakamiya Maru flew over Tsingtau on 5

September, causing something of a surprise to the defenders, on a

reconnaissance and bombing mission, releasing three bombs that caused no harm.

It wasn’t the first aerial bombing ever – that had taken place during the

1911–12 Italo-Ottoman War – but it was a total surprise to the defenders. The

reconnaissance element of the mission was more useful, being able to ascertain

that Emden was not in harbour but that there were several other warships

present. It was to be the first of several visits by both army and navy

aeroplanes, against which the Germans could offer little defence, though the

fact that the defenders had their own air ‘component’ was to result in what was

probably (there are other contenders) the first air-to-air combat in history.

Indeed, despite the remoteness of the campaign from the main theatre, this was

only one of a number of such ‘firsts’.

Aviation on the German side was represented by one man and

one machine; Kapitänleutnant Gunther Plüschow and his Rumpler Taube. Plüschow

had served in the East Asiatic Cruiser Squadron, at the time under the command

of Vice Admiral Carl Coerper, as a junior officer aboard SMS Fürst Bismarck in

1908. Assigned to the Naval Flying Service in autumn 1913, he arrived on 2

January 1914 at Johannisthal Air Field near Berlin to commence pilot training,

and, having first taken to the air only two days previously, acquired his

licence on 3 February 1914. The Naval Air Service, which had been created in

1912 and divided between aeroplane and airship sections the following year,

was, in 1914, something of a misnomer; naval aviation was in a greatly

underdeveloped state with sole assets consisting of two Zeppelin airships, four

floatplanes and two landplanes. This was largely due to Tirpitz, who, despite

his later assertions that, prior to 1914, he saw the aeroplane as the weapon of

the future as against the airship, was not prepared to, as he saw it, divert

funds from the battle-fleet in order to develop the technologies and techniques

required.

Having not seen it for some six years Plüschow arrived in

Tsingtau by train on 13 June – an extremely long and undoubtedly tedious

journey across the Siberian steppe – whilst two Rumpler Taube aeroplanes with

100hp engines, especially constructed for service in China, travelled by sea

arriving in mid-July 1914. The second machine was to be piloted by an army

officer assigned to the III Naval Battalion, Lieutenant Friedrich

Müllerskowski, and the arrival of the two aviators and their machines took the

total ‘air force’ available in the territory to three men and aircraft. The

third aviator was Franz Oster, a former naval officer who had settled in

Tsingtau in 1899, but returned to Germany in 1911 and learned to fly. He returned

to the territory in 1912, via Ceylon (Sri Lanka) complete with a Rumpler Taube

equipped with a 60hp engine. During his sojourn in Ceylon he attempted a flight

at Colombo Racecourse in a Blériot Monoplane on 30 December 1911 that ended in

near disaster; the machine was wrecked and Oster was hurt. He nevertheless,

after having returned to the territory and replaced the engine in his Taube

with a 70hp Mercedes unit, made a series of flights from the Tsingtau

racecourse, the first being on 9 July 1913.

Plüschow and Müllerskowski took charge of reassembling the

two aeroplanes delivered by sea and the former successfully made several

flights from the extremely small and dangerous landing ground at the racecourse

on 29 July 1914. A further two days were needed to get the second aeroplane

constructed, and on the afternoon of 31 July Müllerskowski set off on his first

flight. It ended in disaster; after only a few seconds in flight, and from an

altitude estimated to be 50m, the machine lost control and plunged over a cliff

onto the rocks below. Müllerskowski was seriously, though not mortally, wounded

and the Taube completely wrecked.

Whether it was just bad luck or whether there were

atmospheric conditions pertaining at the time that made flying problematical we

cannot know, but it would seem to have been a combination of the two that

afflicted Plüschow on 3 August. Having taken off successfully and flown a

reconnaissance mission over the territory, his first ‘important’ sortie, he was

experiencing difficulty in attempting to land when his engine failed and he

crash-landed into a small wood. He was unhurt but the Taube was badly damaged

and, upon accessing the spare wings and propellers sent out with the

aeroplanes, he discovered that the replacement parts had rotted away or

suffered moistureinduced damage during the voyage. He was fortunate that the

engine, for which replacement parts could only have been extemporised with

difficulty, was still serviceable and that there were skilled Chinese craftsmen

available; the latter fashioned him a new composite propeller from oak. Despite

this device having to be repaired after every flight, having been assembled

with ordinary carpenter’s glue it exhibited a disconcerting tendency to revert

to its component parts under the strain of operational usage, it remained

serviceable throughout the rest of the campaign.

Plüschow’s machine was out of action until 12 August, but on

the 22 August an attempt was made to augment it with Oster’s aeroplane; he

attempted to lift off from the racecourse in his older craft but stalled and

crashed, occasioning damage necessitating several days of repair though

remaining unhurt personally. Another attempt was made on 27 August with the

same result, though this time the damage was more severe with the aeroplane

‘completely destroyed’ to such an extent that ‘reconstruction was no longer

viable’. It seems however that Oster did not concur as the diary entry for 13

October 1914 made by the missionary Carl Joseph Voskamp, records Oster once

again, and apparently finally, attempting and failing to take off, and notes

that this might be due to unfavourable atmospheric conditions.

Plüschow and his Taube, by default the sole representatives of German aviation, could not of course provide anything much in the way of air defence against the Japanese. Nor could they achieve a great deal in the way of keeping open communications with the world outside the Kiautschou Territory. What was possible though, within the operational capabilities of man and machine, was reconnaissance, and the clearing up somewhat of the weather on 11 September allowed an aerial sortie to take place two days later. Plüschow flew northwestwards to investigate rumours of the Japanese landing and advance, and discovered their forces in some strength at Pingdu; the marching elements of the Japanese force reached Pingdu between 11 and 14 September. He also received his ‘baptism of fire’ from the infantry, returning with around ten bullet holes in his plane and resolving not to fly below 2000m in future in order to preserve his engine and propeller.

#

Reconnaissance duties devolved then on to the air component,

represented by Plüschow and his Taube. There was also a balloon detachment

consisting of two observation-balloon envelopes and the necessary ground

infrastructure. The German observation balloons of 1914 were known as Drachen,

a name commonly adopted for all sausage-shaped kite-balloons, and had been

developed by Parseval-Sigsfeld. Adopted for use in 1893, they represented a

significant investment in terms of equipment and manpower for the Tsingtau

garrison, the standardised balloon section in 1914 consisting of 1 balloon

(plus 1 spare envelope), 4 observers, 177 enlisted ranks, 123 horses, 12 gas

wagons, 2 equipment wagons, a winch wagon and a telephone wagon. The balloon

had made several ascents from Tsingtau during the course of the conflict, but

the observer had been unable to see anything of value. In order to attempt to

remedy this the device was moved closer to the front and another ascent made on

5 October. It was to be the last such, as the Japanese artillery immediately

found its range with shrapnel shell and holed it in several places. A ruse

involving the spare balloon was then tried; it was sent up to draw the

attackers’ fire and so reveal the position of their guns. According to Alfred

Brace:

It contained a dummy looking fixedly at the landscape below

through a pair of paste-board glasses. But there happened to arise a strong

wind which set the balloon revolving and finally broke it loose and sent it

pirouetting off over the Yellow Sea, the whole exploit, I learned afterwards, being

a great puzzle to the British and Japanese observers outside.

Plüschow flew reconnaissance flights every day that the

weather, and his propeller, permitted, sketching the enemy positions and making

detailed notes. He achieved this by setting the engine so as to maintain a safe

altitude of over 2000m, and then steering with his feet, the Taube had no

rudder and horizontal control was achieved by warping the wings, whilst peering

over the side of his cockpit. The Japanese had extemporised a contingent of

antiaircraft-artillery – the ‘Field-Gun Platoon for High Angle Fire’, with the

necessary angle achieved by dropping the gun-trail into a pit behind the weapon

– and although the shrapnel barrage thus discharged proved ineffective it was

deemed by Plüschow to be troublesome nevertheless. Where he was at his most

vulnerable was on landing, and a battery of Japanese artillery was tasked

specifically with destroying the Taube as it descended to the racecourse, which

of course was a fixed point at a known range. Little more than good luck, and

what he called ‘ruses’ such as shutting off the engine and swooping sharply to

earth, saw him through these experiences, but remarkably both man and machine

came through without serious injury.

Whatever inconveniences Plüschow and the fortress artillery

might inflict upon the force massing to their front, they could do nothing to

prevent the landing of men and materiel at Wang-ko-chuang and Schatsykou, nor

could they prevent the deployment of these once landed. The previous efforts by

the navy in terms of minelaying did though still pay dividends, as when the

Japanese ‘aircraft carrier’ was badly damaged. As the report from the British

Naval Attaché to Japan put it in his report of 30 November:

[…] a few minutes after

8 a.m. [on 30 September] the ‘Wakamiya Maru’ struck a mine in the entrance of

Lo Shan Harbour, and had to be beached to prevent her sinking; her engines were

disabled owing to breaking of steam pipes, No. 3 hold full, and one man killed

– fortunately no damage done to aeroplanes though it is feared that a spare

engine may be injured. […] As the Aeroplane establishment is all being moved

ashore at this place this accident will not affect the efficiency of the

Aeroplane Corps.

#

In order to achieve the enormous amount of digging that the

plan required, the organic engineering component of the 18th Division, the 18th

Battalion of Engineers, was augmented by two more battalions; the 1st Battalion

of Independent Engineers (Lieutenant Colonel Koga) and the 4th Battalion of

Independent Engineers (Lieutenant Colonel Sugiyama). The infantry that would

man the siege works were also provided with weaponry specifically suited to

trench warfare; two light platoons and one heavy detachment of bomb-guns

(mortars).

In order to gain detailed knowledge of the defences the

naval and army air components were tasked with flying reconnaissance missions

over the German positions. They also flew bombing missions, which caused little

damage, and attempted to discourage their single opponent (though they were

initially uncertain how many German aircraft they faced) from emulating them;

the latter with some degree of success. Plüschow records that he was provided

with extemporised ‘bombs’ made of tin boxes filled with dynamite and improvised

shrapnel, but that these devices were largely ineffectual. He claimed to have

hit a Japanese vessel with one, which failed to explode, and to have succeeded

in killing thirty soldiers with another one that did. It was during this period

that he became engaged in air-to-air combat, of a type, with the enemy

aeroplanes. Indeed, if Plüschow is to be believed, he succeeded in shooting

down one of the Japanese aeroplanes with his pistol, having fired thirty shots.

It would appear however that even if he did engage in aerial jousting of the

kind he mentions the result was not as he claimed; no aircraft were lost during

the campaign. The Japanese did however do their utmost to prevent him

reconnoitring their positions, as they were in the process of emplacing the

siege batteries and, if the positions became known, they could expect intense

efforts from the defenders to disrupt this process. Experience showed the

Japanese that the time delay between aerial reconnaissance being carried out

and artillery fire being concentrated on the area so reconnoitred was around

two hours.

Indeed Watanabe insisted that his batteries were emplaced

during the hours of darkness, despite the inconvenience this caused, and

carefully camouflaged to prevent discovery. That the threat from Plüschow,

albeit indirect, was very real had been illustrated on 29 September; he had

overflown an area where the British were camped and noted their tents, which

were of a different pattern to the Japanese versions. This had resulted in heavy

shelling, causing the camp to be moved the next day to the reverse slopes of a

hill about 1.5km east of the former position. He also posed a direct threat

though perhaps of lesser import; on 10 October he dropped one of his homemade

bombs on the British. It failed to explode, but the unit concerned moved

position immediately – such an option was not available to 36-tonne howitzers

that required semi-permanent emplacement.

#

The Japanese Navy began sending in vessels to shell the city

and defences again. On 25 October the Iwami approached, though staying outside

the range of Hui tsch’en Huk. By listing the ship to increase the range of her

main armament, Iwami was able to fire some thirty 305mm shells at Hui tsch’en

Huk, Iltis Battery and Infantry Work I. The next day the vessel returned in

company with Suwo and the two vessels bombarded the same targets. On 27 October

Tango and Okinoshima replaced them, and the same ships returned the next day to

continue the assault. Because of the distance involved, some 14.5km, this fire

was inaccurate in terms of damaging the specific installations in question, but

nevertheless was destructive of the nerves of the trapped garrison. It was

particularly frustrating in terms of the gunners at Hui tsch’en Huk who were

unable to effectively reply.

In addition to this display of naval force, Japanese air

power had been much in evidence over the period, their operational activity

increasing with sorties over the German lines and rear areas.

Almost every day these craft, announcing their approach by a

distant humming, came overhead, glinting and shining in the sun as they sailed

above the forts and city. At first they were greeted by a fusillade of shots

from all parts of the garrison. Machine guns pumped bullets a hundred a minute

at them and every man with a rifle handy let fire. As these bullets came

raining back upon the city without any effect but to send Chinese coolies

scampering under cover, it was soon realised that rifle and machinegun fire was

altogether ineffective. Then special guns were rigged and the aeroplanes were

subjected to shrapnel, which seemed to come nearer to its sailing mark each day

but which never brought one of the daring bird-men down. One day I saw a

biplane drop down a notch after a shell had exploded directly in front of it. I

looked for a volplane [glide with engine off] to earth, but the aviator’s loss

of control was only momentary, evidently caused by the disturbance of the air.

During the bombardment these craft circled over the forts like birds of prey.

They were constantly dropping bombs, trying to hit the ammunition depots, the

signal station, the Austrian cruiser Kaiserin Elizabeth, the electric light

plant, and the forts. But […] these bombs were not accurate or powerful enough

to do much damage. A few Chinese were killed, a German soldier wounded, tops of

houses knocked in, and holes gouged in the streets, but that was all. The bombs

fell with an ominous swish as of escaping steam, and it was decidedly

uncomfortable to be in the open with a Japanese aeroplane overhead. We are more

or less like the ostrich who finds peace and comfort with his head in the sand:

In the streets of Tsingtau I have seen a man pull the top of a jinrickisha over

his head on the approach of a hostile aeroplane and have noticed Chinese

clustering under the top of a tree.

They also managed an aviation first on the night of 28–9

October when they bombed the defenders’ positions during the hours of darkness.

Attempts to keep Plüschow from effectively reconnoitring were largely

successful, even though the efforts to dispose of him or his machine

permanently were ineffective. However, because problems with the Taube’s

homemade propeller kept him grounded on occasion, and because the Japanese

positions were worked on tirelessly, when he did take to the air he found the changes

in the enemy arrangements – ‘this tangle of trenches, zigzags and new

positions’ – somewhat bewildering and difficult to record accurately. Precision

in this regard was not assisted by the Japanese attempts to shoot him down or

otherwise obstruct him.

The artillery coordinating position on Prinz-Heinrich-Berg

reported itself ready for action on 29 October and Kato sent four warships in

to continue the naval bombardment whilst acting under its direction. Between

09:30hr and 16:30hr Suwo, Tango, Okinoshima and Triumph bombarded the Tsingtau

defences, adjusting their aim according to the feedback received from the

position via radio. They withdrew after discharging some 197 projectiles from

their main guns, following which SMS Tiger was scuttled during the hours of

darkness.

Plüschow managed to get airborne on the morning of 30

October and was able to over-fly the Japanese positions before the enemy air

force could rise to deter him. This might have been lucky for him as one of the

aeroplanes sent up had been fitted with a machine gun. He was able to report

the largescale and advanced preparations of the besieging force, information

that the defence used to direct its artillery fire. This was repaid when Kato’s

bombarding division returned at 09:00hr to recommence their previous day’s

work. Despite the communication channel working perfectly, and the absence of

effective return fire from Hui tsch’en Huk – they had established the maximum

range of this battery was 14.13km and accordingly stayed just beyond its reach

– the firing of 240 heavy shells again did little damage.

The 31 October was, as the defenders knew well, the birthday

of the Japanese Emperor and by way of celebration Kamio’s command undertook a

brief ceremony before, at about 06:00hr, Watanabe gave the order for the siege

train to commence firing, or, as one of the correspondents of The Times put it:

‘daylight saw the royal salute being fired with live shell at Tsingtau’. The

Japanese fire plan was relatively simple.

On the first and second days, in addition to bombardment of

the enemy warships, all efforts would be made to silence the enemy’s artillery

so as to assist the construction and occupation of the first parallel.

From the third day up until the occupation of the second

parallel (about the fifth day) the enemy artillery would be suppressed, his

works destroyed and the Boxer Line swept with fire in order to assist in the

construction of the second parallel.

Following the occupation of the second parallel, the

majority of the artillery fire would be employed in destroying the enemy’s

works, whilst the remainder kept down hostile infantry and artillery that

attempted to obstruct offensive movement in preparing, and then assaulting

from, the third parallel.

After the Boxer Line had been captured, the artillery would

support the friendly troops in securing it from counter-attack and then bombard

his second line; Iltiss, Moltke and Bismarck Hills.

There were, roughly, twenty-three Japanese artillery tubes

per kilometre of front, a density that was comparable to that attained during

the initial stages of the war on the Western Front, though soon to be dwarfed

as artillery assumed the dominant role in positional warfare. The land-based

artillery was augmented, from about 09:00hr, by the naval contribution as Kato

once again sent his heavy ships into action.

The combined barrage soon silenced any German return fire

because, even though they had refrained from pre-registering their siege

batteries, the Japanese knew where the fixed defensive positions were and

shortly found their range; fire was also brought to bear on any targets of

opportunity. The German batteries were suppressed less by direct hits than by

their positions being submerged in debris from near misses. This was to prove

of some importance for the defenders were able in several cases to return their

weapons to service, largely due to the relative antiquity and thus lack of

sophistication of much of the ordnance, without the need for extensive repairs.

Indeed, despite the crushing superiority enjoyed by the attackers, the

defensive fire was to continue to some degree throughout the day and into the

night. The most obvious sign of the effects of the bombardment, at least to

those observing from a distance, were the huge plumes of smoke caused by hits

on the oil storage tanks adjacent to the Large Harbour. Two of these, owned by

the Asiatic Petroleum Company – the first Royal Dutch/Shell joint venture – and

Standard Oil respectively, had been set afire early on and their contents in

turn caused other fires as they flowed around the installations, these proving

beyond the capacity of the local fire brigade to control. In fact the

destruction of the Standard Oil installations was accidental. The General Staff

History records that a note had been received via the Japanese Foreign Office

from the US government asking that they be spared. Accordingly the objective

was struck out of the plan but to apparently no effect, perhaps demonstrating

the relative inaccuracy of the fire.

There were a number of independent observers of the

operations at this stage; correspondents from various journals and foreign

military observers had arrived in the theatre in late October. Though the

Japanese were intensely secretive they could not conceal the fact of their

bombardment or the plainly visible results.

The thunder of the great guns broke suddenly upon that

stillness which only dawn knows, and their discharges flashed readily on the

darkling slopes. The Japanese shooting, it is related, displayed remarkable

accuracy, some of the first projectiles bursting upon the enormous oil tanks of

the Standard Oil Company and the Asiatic Petroleum Company. A blaze roared

skywards, and for many hours the heavens were darkened by an immense cloud of

black petroleum smoke which hung like a pall over the town. Shells passing over

these fires drew up columns of flame to a great height. Chinese coolies could

be seen running before the spreading and burning oil. Fires broke out also on

the wharves of the outer harbour.

Many of the Japanese shells, no doubt due to the lack of

pre-registration, were over-range and landed in Tapatau and Tsingtau, though

the former received the worst of it. It has been estimated that at least 100

Chinese were killed during this period and a deliberate targeting exercise

carried out later in the day on the urban areas. The bombardment continued with

varying levels of frequency throughout the daylight hours of 31 October, and at

nightfall the Japanese gunners switched to shrapnel – by bursting shrapnel

shell over the defenders’ positions they made it difficult, if not impossible,

for repairs to be carried out. Such fire also covered the forward movement of

the Japanese engineers as they extended their saps towards the Boxer Line and

began constructing the parallel works some 300m ahead of the advanced

investment line.

At daylight on 1 November the high-explosive barrage

resumed, again concentrating primarily on the German artillery positions though

many of these were now out of action. The secondary targets were the defences

in the Boxer Line, particularly the infantry works and the extemporised

defences between them. The ferro-concrete redoubts withstood the bombardment

without any serious damage, and, though they were scarred and badly battered externally,

none of the projectiles penetrated any vital interior position. The

communication trenches and other intermediate field works were however

obliterated and this, together with the destruction of much of the telephone

system, isolated the personnel manning the works, both from each other and from

the command further back. The targeting of the signal station further hindered

communication of every kind, and with the bringing down of the radio antenna

even one-way communication from the outside world was terminated. Shutting this

down was probably a secondary objective; the primary reason for targeting the

signal station was to prevent it jamming and otherwise interfering with

Japanese wireless communications which had become a problem.

After nightfall the sappers returned to their task of

advancing the siege works whilst infantry patrols went forward to reconnoitre

and probe the defences. One such probe crossed the Haipo and a four-man party

entered the ditch near Infantry Work 4, which was under the command of Captain

von Stranz, and began cutting the wire. They remained undetected for some time,

indicating the lack of awareness of the defenders who stayed under cover, but

were eventually heard and forced to retire with the loss of one man after machine-gun

fire was directed at them. A second patrol took their place a little later and,

under the very noses of the defence, completed the wire-cutting task before

they too were detected.

The defenders conceived that an assault in strength was

under way and called down artillery fire in support from Iltis Battery and

moved a reserve formation made up of naval personnel, whose ships had been

scuttled, towards the front. The Japanese patrol withdrew, leaving the

defenders under the erroneous impression that they had defeated a serious

attempt at breaching the line, rather than, as was the case, an opportunistic

foray. However, what the probe had revealed to the attackers was that the

defenders were remaining largely inside the concrete works, leaving the gaps

between them vulnerable to infiltration. This was confirmed by the experiences

of a separate patrol that reconnoitred near Infantry Work 3, also known as the

‘Central Fort’ to the Japanese; the knowledge gained being of some potential

worth. Also of value was an understanding of the nature of the barbed-wire

obstacles. These were permanent fixtures, with extra heavy wire holding barbs

‘so closely together that it would be difficult to get a pair of pliers in a

position to cut it’. It did prove possible to cut the wire, but the stakes it

was strung on, made from heavy duty angle-iron secured to a square baseplate

some 300mm per side and sunk into the ground to a depth of about half a metre,

proved almost impossible to dislodge. Initial intelligence had indicated that

the wire was charged with 30,000 volts, but direct examination showed this not

to be the case.

Apart from repelling the Japanese attack, as they thought,

the defenders spent the night of 1–2 November destroying further equipment that

might be of use to the besiegers. Chief amongst this was Kaiserin Elisabeth;

shortly after midnight, having fired off her remaining ammunition in the

general direction of the Japanese, the vessel was moved into deep water in

Kiautschou Bay and scuttled. Explosive charges extemporised from torpedo

warheads ensured that the ship was beyond salvage even if the wreck was

located. The Austro-Hungarian cruiser was only one of several vessels scuttled

that night, including the floating dock, which was seen to have disappeared the

next morning. Only the Jaguar remained afloat at sunrise at which point the

rapid rate of advance of the attackers, up to the edge of the Haipo River

between Kiautschou Bay and the area in front of Infantry Work 3, was revealed

to the Germans.

Revealed to the Japanese, by their action during the hours

of darkness, was the precise position of the Iltis Battery and this was

promptly targeted and put out of action by counter-battery fire. The

remorseless battering by the siege train also resumed, and the German inability

to respond effectively due to the accuracy of Japanese return fire began to be

exacerbated by a shortage of ammunition. The Japanese bombardment, though

intense, was perhaps not as destructive as it could have been. What seems to

have mitigated the effect to some extent was the high rate of dud shells. One

press correspondent that entered Tsingtau after the conclusion of operations

noted the proliferation of ‘giant shells, some three feet long and a foot in

diameter, [that] were lying about on side-walk and street still unexploded’.

Burdick, working from contemporary German estimates, calculates that between 10

and 25 per cent of the Japanese ordnance failed to explode. This shortcoming,

being attributable to faulty manufacture, played a major role in sparing the

defenders a worse ordeal than they had to endure anyway.

Also sparing the defenders to some extent on 2 November was

the onset of rain, which affected the assailants more than the defence inasmuch

as the attackers’ diggings became waterlogged and collapsed in some cases.

Further alleviation was attributable to the reduction of the rate of fire of

the 280mm howitzers. Their temporary emplacements suffered from the immense

recoil and had the potential to render firing both dangerous and inaccurate.

The remainder of the siege train concentrated its fire on the Boxer Line,

particularly in an attempt to destroy the wire and obstacles in the trench and

thus mitigate the need to resort to manual methods with their inevitable human

cost. The power station was also targeted, with the result that the chimney was

brought down in the evening, thus rendering the city dependent on primitive

forms of lighting.

The 3 and 4 November saw further progress in the advancement

of the siege works and continuing bombardment, though useful targets for this

were now at a premium as little of the defences remained other than the

concrete Infantry Works. The defenders had begun destroying their batteries on

2 November as they ran out of ammunition, and in any event returning the

Japanese fire was a hazardous business due to the rapidity and accuracy of the

response. The lack of defensive fire allowed some reorganisation of the siege

artillery and several of the batteries were moved forward and swiftly

re-emplaced with the minimum of disruption. On the far right of the Japanese

line the sappers attached to 67th Infantry Regiment had advanced their works to

within a short distance of the Haipo River, and thus close to the city’s water

pumping station situated on the eastern bank. The decision was taken by 29th

Infantry Brigade to attempt to take the station on the evening of 4 November

and a company sized unit, comprising infantry and engineers, was assembled. It

had not been bombarded by the siege artillery; the idea seemingly being to

preserve it for future use by the occupying force. So the engineers cut through

the defensive wire with Bangalore Torpedoes, thus allowing the infantry to

surround the place, whilst a box artillery barrage insulated it from any

attempted relief.

Despite its relative isolation the pumping station was

actually a wellfortified strongpoint. The machinery rooms, stores and personnel

quarters were located underground and well protected by ferro-concrete. The

whole was surrounded by a bank of earth some 6m in height, itself protected by

a ditch, about 12m wide and 2m deep at the counterscarp, that was filled with

barbed-wire obstacles. The leader of the platoon investigating the area, 2nd

Lieutenant Yokokura, later reported that the personnel manning the station had

locked themselves inside behind ‘iron doors’ and were still working the pumps,

but when they realised that the enemy were upon them they opened the doors and

surrendered. The haul amounted to one sergeant major, twenty rank and file, two

water works engineers and five Chinese, together with twenty-five rifles. The

station was immediately fortified against any counter-attack and with its loss

Tsingtau was without a mains water supply and thus dependent on the several,

somewhat brackish, wells within the city.

Elsewhere along the line the nocturnal ‘mole warfare’

techniques advanced the saps and trenches ever nearer to the ditch in order to

construct the third parallel – the final assault line. This progressed

everywhere apart from the British sector of front, where enemy fire prevented

the final approach being made. As Barnardison reported:

On 5 November I was

ordered to prepare a Third Position of attack on the left bank of the river.

This line was to a great extent enfiladed on both flanks by No. 1 and 2

Redoubts, especially the latter, from which annoying machine-gun fire was

experienced. The bed of the river […] had also to be crossed, and in doing so

the working parties of the 2nd Battalion South Wales Borderers suffered

somewhat severely, losing 8 non-commissioned officers and men killed and 24

wounded. The 36th Sikhs had only slight losses. Notwithstanding this a good

deal of work was done, especially on the right flank. I considered it my duty

to represent to the Japanese Commander-in-Chief the untenable nature, for

permanent occupation, of the portion of the Third Position in my front, but

received a reply that it was necessary for it to be held in order to fit in

with the general scheme of assault.

Though most diplomatically phrased, it is possible to

distinguish in the final sentence of this quotation a hint of asperity in the

relations between the Allies. Indeed, though suppressed for political reasons

at the time, the British military contribution did not impress the Japanese in

any way, shape or form. Reports from the front revealed the perception that the

British were reluctant to get involved in the fighting and ‘hard to trust’.

More brutal opinions had it that they were no more than ‘baggage’ and ‘decoration’

on the battlefield. The nature of these observations filtered through to the

Japanese press, one report stating that: ‘Only when nothing happened were

British soldiers wonderful and it was like taking a lady on a trip. However,

such a lady can be a burden and lead to total disaster for a force when the

enemy appears.’

Daylight on 5 November saw three Japanese aeroplanes overfly

the German positions dropping not explosive devices, as might have been

expected, but rather bundles of leaflets carrying a message from the besiegers:

To the Respected

Officers and Men of the Fortress.

It would act against

the will of God as well as humanity if one were to destroy the still useful

weapons, ships, and other structures without tactical justification and only

because of the envious view that they might fall into the hands of the enemy.

Although we are certain in the belief that, in the case of

the chivalrous officers and men, they would not put into effect such

thoughtlessness, we nevertheless would like to emphasise the above as our point

of view.

On the face of it this message seemed to clearly indicate

that the besiegers, perceiving that they would shortly be in occupation of the

city, desired that as much of it be preserved as was possible. If so they

adopted a rather contradictory attitude inasmuch as shortly after dispensing it

a naval barrage, delivered by Mishima, Tango, Okinoshina and Iwami from Hai hsi

Bay to the west of Cape Jaeschke, was directed onto the urban area of Tsingtau.

Backed by the land batteries, this bombardment caused great damage to the city,

though one shot, apparently misaimed, struck one of the 240mm gun positions at

Hui tsch’en Huk, destroying the gun and killing seven of the crew. Without a

mains water supply the possibility of fire-fighting in Tsingtau was greatly reduced

and several buildings were burned down, though because of the relative

spaciousness of the city fires did not jump easily from building to building

and so there was no major conflagration. Tapatau, the Chinese quarter, was not

constructed on such generous proportions, though the relatively smaller size of

the dwellings and their less robust structural strength meant they collapsed

rather than burned, and it too was spared an inferno. Because the German

artillery was now virtually silent the sapping work continued during daylight

hours without fear of interruption, and the third parallel was completed during

the day close up to the defensive ditch. Unable to effectively counter these

moves the defenders, also ignoring the Japanese plea as contained in their

airdropped leaflet, began putting their coastal artillery batteries out of

action, which in any event, other than Hui tsch’en Huk, had proved mostly

ineffective. It was clear to all that the end was not far off, and only the

ferro-concrete infantry works remained as anything like effective defensive

positions, though a report from one to Meyer-Waldeck ‘reflected the universal

condition’:

The entire work is shot to pieces, a hill of fragments,

without any defences. The entire trench system is knocked out; the redoubt

still holds together, but everything else, including the explosives storage

room, is destroyed. Only a single observation post is in use. I shall hold the

redoubt as long as possible.

Given the impossibility of offering effective resistance to

the besiegers, Meyer-Waldeck was under no illusions as to the length of time

left to the defence force. Evidence for this may be adduced from his ordering

Plüschow to make a getaway attempt the following day. He was to carry away

papers relating to the course of the siege and several symbolic items such as

the fastenings from the flagpole, as well as private letters from members of

the garrison.

The attackers saw the elusive Taube take to the air the next

morning, and, according to Plüschow himself, make a last circuit of Tsingtau

before setting off southwards; ‘never,’ as the Japanese General Staff history

put it, ‘to come back’. Though the Japanese artillery made what was to turn out

to be their final efforts to shoot him down, hostile aircraft did not attempt

to follow and he made good his escape towards neutral China, eventually

reaching Tientsin where he was reunited with the crew of S-90. As he left his

ground crew destroyed any remaining equipment, but his place over the city was

soon taken by the Japanese aeroplanes who sortied in force, dropping numerous

bombs onto the defenders’ positions, as a less than effective adjunct to the

efforts of the artillery. As the bombardment from land and air went on the

Japanese infantry began to move into their final assault positions in the third

parallel. The British however, still troubled by the fire from the German

machine guns, only occupied their sector with a thin outpost line. The

Governor, noting the proximity of the attackers and expecting an imminent assault,

ordered a general alert for the afternoon.

Kamio now had all his infantry where he wanted them, with

the exception of the British contingent, and all his equipment in place. His

orders for the night of 6–7 November did not however call for a general

assault, but rather stipulated small scale, though aggressive, probing of the

Boxer Line to test for weak spots, together with the usual artillery barrage.

He emphasised flexibility and the exploitation of success. As darkness fell the

sappers dug forward from the third parallel and, using mining techniques,

burrowed through the counterscarp before blowing several breaches in it. This

allowed the infantry direct access to the ditch without the need to leave the

entrenchments. It was also discovered that the ditch in front of Infantry Works

1 and 2 differed somewhat from the saw-tooth version already noted, being a

conventional channel in section. It was also found to be subject to flanking

fire from the Central Fort (Infantry Work 3).

Wire that had remained intact following the previous

attention of the artillery was cut or covered, allowing more or less

unrestricted access within the ditch, and patrols moved across it and out onto

the German side as darkness fell. At around 23:00hr a firefight broke out around

Infantry Work 2 as a patrol from the 56th Infantry Regiment attempted to

infiltrate and bypass it. The defenders were more alert than they had been on 1

November and sallied out to meet them. Eventually, after about an hour of

fighting, the Japanese retreated and called down an artillery barrage onto the

defenders for their pains.

More or less concurrently Infantry Work 3 (Central Fort)

under the command of Captain Lancelle was the object of similar tactics. The

results were however rather different. Engineers from the 4th Independent

Battalion, preceding units from the 56th Infantry Regiment, discovered that

they met with no resistance whatsoever when they began cutting two ‘roads’

through the entanglements in both the inner and outer ditches in front of the

fortification. Accordingly this work was completed expeditiously, and the

information on the apparent passivity of the defenders in that sector passed up

the chain of command. Major General Yamada, commander of the 2nd Central Force,

immediately decided to attempt an assault to take the work, but sought the

sanction of Kamio before so doing. The division commander concurred, so a

company sized unit under Lieutenant Nakamura Jekizo of the 56th Infantry

Regiment crossed the ditch at about 01:00hr.

The plan required some courage on the part of the

participants, who were all volunteers. They comprised twenty engineers and six

infantry NCOs who were armed with hand grenades, whilst further infantry units,

complete with mortars, stood ready in immediate support. The whole regiment was

also awaiting developments and was ready to advance at a few minutes’ notice.

Formed into two detachments, the raiders used ladders to climb into the ditch

away from the breach and, unseen, safely reached the German parapet which they

scaled before moving to reform. The plan called for a stealthy advance until

the occupants of the redoubt opened up on them, and then a charge forward

throwing the grenades in an attempt to disable the defenders and damage the

machine guns. This procedure was modified when it became apparent that the

fortification was, effectively, unguarded and Nakamura instead sent his men

left and right around it to the rear (or ‘gorge’ in fortification terms) where

they occupied the shelter trenches.

Detailing ten grenadiers and an NCO to resist any German

potential counter-attack, he used the rest of his men to block the redoubt’s

exits and then sent for reinforcements. Before these could arrive however the

Japanese were detected by defence posts on the flanks of the fortification,

whereby a hot fire with machine guns was opened. Several volleys of grenades

stemmed that, and in the meantime the redoubt’s telephone wires were cut and

access was forced into the signal room where, after the occupants were overcome,

the power was cut. This plunged the whole work into darkness and prevented any

further telephoning or signalling.

By this time two platoons of reinforcements had begun to

arrive; half of them formed a defensive line behind the redoubt whilst the rest

broke into it. It was claimed that they found the occupants in bed, but

whatever the truth of the matter Lancelle immediately surrendered the work

complete with its complement of about 200 men to Nakamura. It had taken forty

minutes and been, to quote Burdick’s words, ‘ridiculously easy’. It was

undoubtedly a famous and daring victory, and Nakamura was awarded the Order of

the Golden Kite (4th class) which he undoubtedly deserved.

In practical terms however, there was now a large and

growing gap in the very centre of the Boxer Line, and word quickly got to

Meyer-Waldeck who ordered his reserves to counter-attack under cover of a

German barrage. Whilst such a move was theoretically sound, it was,

practically, almost impossible. There was simply not enough artillery left to

provide an effective bombardment, and precious little manpower, particularly in

comparison with that available to the attackers, to seal the breach. The effort

was made, but the counter-attackers, including a contingent of Austro-Hungarian

sailors landed from Kaiserin Elisabeth, were simply too weak to throw back the

rapidly reinforcing Japanese.

The Boxer Line, being a linear defence, was vulnerable to

being ‘rolled up’ from the flanks once breached at a given point. The Japanese

having made the breach now proceeded to widen it by moving against Infantry

Works 2 and 4 on either side. Both works held out for some hours, assisted by

the Jaguar, the last German warship afloat, which fired away her remaining

ordnance in support. The outcome however could be in no doubt and both works

surrendered after about three hours of resistance. The Boxer Line was now

useless, for with no defence in depth the penetration meant the route to

Tsingtau was now as good as wide open. The Japanese infantry surged through the

gap and began a general advance on Tsingtau and various strategic points, such

as Iltis and Bismarck Hills. The batteries on the former fought the attackers

for a time before surrendering, whereas the artillerymen on the latter, having

fired away the last of their ammunition, set charges to destroy their guns and

vacated the position at about 05:00hr. This final destruction of land-based

artillery had its counterpart on the water; Jaguar, after attempting to repulse

the infantry attack, had been scuttled in Kiautschou Bay.

At 06:00hr Meyer-Waldeck held a meeting at his headquarters

in the Bismarck Hill Command Post where the latest information was assimilated.

It had long been an unwritten rule of siege warfare that a garrison could

honourably surrender following a ‘practical breach’ being made in their

defences. The Japanese, using classic siege warfare methodology, had now

achieved just such a breach. Whether the Governor was aware of the ‘rule’ is

unknown, but he had now only two options; surrender or a fanatical ‘fight to

the last man and last bullet’ scenario. Meyer-Waldeck was no fanatic. Brace put

it thus:

If the governor had

permitted the unequal struggle to go on his men would have lasted only a few

hours longer. It would be an Alamo, and the name of the German garrison would

be heralded throughout history as the heroic band of whites who stood against

the yellow invasion until the last man. On the other hand the governor had with

him a large part of the German commercial community of the Far East which

Germany had built up with such painstaking care.

The Governor ordered the white flag hoisted on the signal

station and over the German positions and composed a message to Kamio: ‘Since

my defensive measures are exhausted I am now ready to enter into surrender

negotiations for the now open city. […] I request you to appoint

plenipotentiaries to the discussions, as well as to set time and place for the

meeting of the respective plenipotentiaries. […]’ The carrier of this message

was Major Georg von Kayser, adjutant to Meyer-Waldeck’s Chief-of-Staff, naval

Captain Ludwig Saxer – the latter being the Governor’s appointee as German

plenipotentiary. Despite Barnardiston’s contention that all firing ceased at

07:00hr Kayser had difficulty getting through the lines in safety, but he was

eventually allowed to proceed under his flag of truce to the village of

Tungwutschiatsun, some 4km behind the Japanese front line, more or less

opposite the celebrated Central Fort (Infantry Work 3).81 It was agreed that a

general armistice would come into play immediately, and that formal

negotiations for the capitulation would commence that afternoon at 16:00hr in

Moltke Barracks.