Map of the American Naval Operations in Korea, 1871.

The largest-scale combat in which Leathernecks participated in the three decades following the Civil War was the Korean Expedition of 1871. On 23 May of that year, five vessels of Rear Admiral John Rodgers’s Asiatic Fleet—the frigate Colorado, sloops Alaska and Benicia, and gunboats Monocacy and Palos—entered Roze Roads on the west coast of Korea not far from Chemulpo (modern-day Inchon). Aboard Admiral Rodgers’s flagship, the Colorado, was Frederick F. Low, the U.S. minister to China, who had been sent to open diplomatic relations with the hermit kingdom of Korea. Contact was made with the local inhabitants, and on the 31st a small delegation of third- and fifth-rank Korean officials appeared. Low refused to receive them, directing his secretary to explain that the presence of first-rank officials qualified to conduct negotiations was required. In the meantime, the Koreans were informed, the Americans desired to chart the Salee River, as the channel of the Han River between Kanghwa-do (island) and the Kumpo Peninsula was then called. As the Han leads to the capital city of Seoul, the Koreans might have been expected to consider such an act provocative, American assurances of goodwill notwithstanding, but they raised no objections. Twenty-four hours were allotted for them to notify the appropriate authorities.

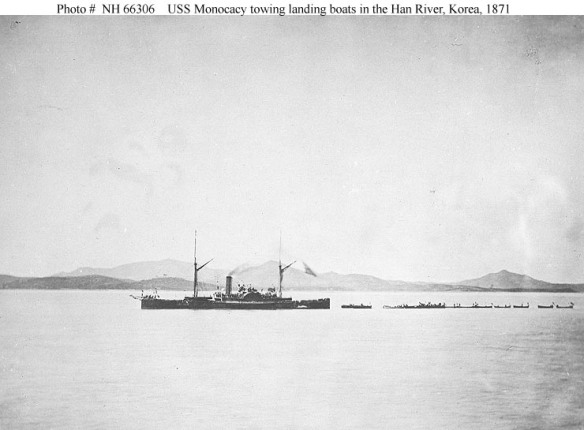

Accordingly, at noon on 1 June, four steam launches followed by the Monocacy and Palos set out to begin the survey. As they came abreast of the fortifications on the heights of Kanghwa-do, the Koreans opened fire. The surveying party replied with gusto, shelling the forts into silence, and returned to the fleet’s anchorage. American casualties were two men wounded.

Admiral Rodgers waited nine days for an apology or better tides. The former was not forthcoming, and on 10 June a punitive expedition entered the river with the mission of capturing and destroying the errant forts. The landing force numbered 686 officers and men, including 109 Marines organized into two little companies and a naval battery of seven 12-pounder howitzers. Fire support would be provided by the gunboats and four steam launches mounting 12-pounders in their bows. Commander L. A. Kimberly was placed in command of the landing force; Captain McLane Tilton led its Leathernecks. Tilton was one of those unconventional characters for whom the Corps has always seemed to exercise an attraction. (Writing his wife from a Mediterranean deployment, he reported that when he first went on deck each day, “If anyone asks me how are you old fellow, I reply, ‘I don’t feel very well; no gentleman is ever well in the morning.’”)

Three forts, each with a walled water-battery, overlooked the shore of Kanghwa-do. In the course of the operation, the Americans christened them the Marine Redoubt, Fort Monocacy, and The Citadel. The Monocacy took the first two under fire shortly after noon. Both had been silenced by the time the Palos appeared with the landing party’s boats in tow about an hour later. The boats cast off half a mile below the nearest fort, and at 1345 that afternoon the Bluejackets and Marines began struggling ashore across a broad, knee-deep mudflat “crossed by deep sluices,” a disgusted Tilton noted, “filled with softer and still deeper mud.” Some men left their shoes, socks, leggings, and even trouser legs behind, and the howitzers bogged down to their barrels. Fortunately, the Koreans did not attempt to oppose the landing.

The Leathernecks had been selected to serve as the expedition’s advance guard. Tilton deployed them into a skirmish line as soon as they left the boats. Once both companies reached firm ground, Commander Kimberly ordered Tilton to lead his Marines toward the fort, an elliptical stone redoubt with 12-foot walls. Most of the sailors remained behind to manhandle the guns out of the muck. On the Marines’ approach, the fort’s white-robed defenders fled, firing a few parting shots. The work mounted 54 guns, but all except two were insignificant brass breechloaders. Tilton halted his men until the main body came up, “when we were again ordered to push forward,” he wrote, “which we did, scouring the fields as far as practicable from the left of the line of march, the river being on our right, and took a position on a wooded knoll . . . commanding a fine view of the beautiful hills and inundated rice fields immediately around us.” At this point he received orders to hold for the night. It was 1630 before the guns had been dragged ashore, and too few hours of daylight remained to demolish the captured fort and tackle the next. The seamen bivouacked half a mile to the rear.

The landing force moved out at 0530 the next morning. Its fire support had been reduced by the withdrawal of the Palos, which had hurt herself on an uncharted rock while the landing was in progress, but that available from the Monocacy and the launches would prove more than sufficient. The second fort, a chipped granite structure about 90 feet square, stood on a bluff a mile upstream. Tilton’s men found it deserted. While a Marine bugler amused himself by rolling 33 little brass cannon over the bluff into the river, other members of the expedition spiked the fort’s four big guns and tore down two of its walls. The march was then resumed.

The track between the first two forts had been relatively easy going, but beyond the second it became extremely difficult, “the topography of the country being indescribable,” Tilton reported, “resembling a sort of ‘chopped sea’ of immense hills and deep ravines lying in every conceivable position.” Presently the column came under long-range musket fire from a Korean force estimated to number from 2,000 to 5,000 among some hills beyond the Americans’ left flank. Five guns supported by three companies of seamen were deployed to hold this body in check, and the remainder of the party continued its advance. On two occasions the Koreans made a rush toward the detachment, but a few artillery shells turned them back each time.

The last and strongest of the Korean fortifications, The Citadel, was a stone redoubt crowning a steep, conical hill on a peninsula some two miles upstream from its neighbor. The Monocacy and the steam launches opened fire on the Citadel at about 1100. At noon, Commander Kimberly halted his command 600 yards from the fort to give the men a breather. By that time, the parties of Koreans seen falling back on The Citadel and the forest of flags in and around it left no doubt that the position would be defended.

After signaling the Monocacy to cease fire, the storming party, 350 seamen and Marines with fixed bayonets, dashed forward to occupy a ridgeline only 120 yards from the fort. Although Tilton’s men were still armed with the model 1861 muzzle-loading Springfield rifle musket (in his words “a blasted old ‘Muzzle-Fuzzel’”), they quickly established fire superiority over the fort’s defenders, who were armed with matchlocks, a firearm that had disappeared from Western arsenals 200 years before. “The firing continued for only a few minutes, say four,” Tilton wrote, “amidst the melancholy songs of the enemy, their bearing being courageous in the extreme.”

At 1230 Lieutenant Commander Silas Casey, commanding the Bluejacket battalion, gave the order to charge. “[A]nd as little parties of our forces advanced closer and closer down the deep ravine between us,” Tilton continued, “some of [the Koreans] mounted the parapet and threw stones etc., at us, uttering the while exclamations seemingly of defiance.” The first American into The Citadel, Navy Lieutenant Hugh W. McKee, fell mortally wounded by a musket ball in the groin and a spear thrust in the side. The spearman also stabbed at Lieutenant Commander Winfield Scott Schley, who had followed close behind McKee. The point passed between Schley’s left arm and his chest, pinning his sleeve to his coat, and he shot the man dead.

Tilton was among half a dozen officers who led their men into the fort moments later. The Koreans stood their ground, and the fighting became hand to hand. Clambering over the parapet, Private Michael McNamara encountered an enemy soldier pointing a matchlock at him. He wrenched the gun from the Korean’s hands and clubbed him to death with it. Private James Dougherty closed with and killed the man the Americans identified as the commander of the Korean forces. Tilton, Private Hugh Purvis, and Corporal Charles Brown converged on The Citadel’s principal standard, a 12-foot-square yellow cotton banner emblazoned with black characters signifying “commanding general.” For five minutes the fort’s interior was a scene of desperate combat. Then the remaining defenders fled downhill toward the river, under fire from the Marines, a company of seamen, and the two howitzers that had accompanied the attackers.

A total of 143 Korean dead and wounded were counted in and around the Citadel, and Lieutenant Commander Schley, the landing force’s adjutant, estimated that another 100 had been killed in flight. Forty-seven flags and 481 pieces of ordnance, most quite small but including 27 sizable pieces—20-pounders and upward—were captured. The storming party lost three men killed and ten wounded, with a Marine private in each category. Captain Tilton was pleasantly surprised by his survival. In a letter home a few days later, he wrote, “I never expected to see my wife and baby any more, and if it hadn’t been that the Coreans [sic] can’t shoot true, I never should.” He retired as a lieutenant colonel in 1897. Nine sailors and six Marines were awarded the Medal of Honor. Among the latter were Corporal Brown and Private Purvis, who had rendezvoused with Tilton at the Citadel’s flagstaff.

The landing force reembarked early the next morning, leaving The Citadel in ruins. “Thus,” wrote Admiral Rodgers, “was a treacherous attack upon our people and an insult to our flag redressed.” Successful as it had been from a military standpoint, however, the operation was not a masterstroke of diplomacy. Subsequent communications with Korean authorities, conducted by messages tied to a pole on an island near the anchorage, were entirely unproductive, and on 3 July the fleet withdrew. A treaty with Korea was not negotiated until 1882.

Marine Amphibious Landing in Korea, 1871