SURPRISE WAS IMPOSSIBLE in the bitterly contested Gavutu-Tanambogo landings as depicted in this overprint. The photograph itself was taken by Japanese aircraft early in 1942 prior to enemy seizure of the Tulagi-Guadalcanal area.

Landings on and fighting across Tulagi.

Landings on Gavutu and Tanambogo.

The amphibious assault on Guadalcanal and Tulagi was the first U. S. ground offensive of World War II. Designated Operation Watchtower, the hastily thrown together plan called for the 1st Marine Division, about 19,000 men, supported by American and Australian warships and transport vessels, 82 ships of all types, to make the seaborne assault. The Allied armada assembled near Fiji on July 26. A poorly planned and executed rehearsal, Operation Dovetail, was held on Koro Island in the Fijis, after which the fleet sailed for its objectives on the 31st.

As the Allied fleet neared Guadalcanal, it split: the Guadalcanal Group, made up of Combat Group A composed of the 1st and 5th Marine Regiments, the divisional artillery, and support units (11,300 men), under 1st Marine Division commander Maj. Gen. Alexander A. Vandegrift, headed for Lunga Point on Guadalcanal. The Northern Group, built around four Marine infantry rifle battalions (2,400 troops), led by assistant division commander Brig. Gen. William H. Rupertus, steered for Tulagi, Florida, Gavutu, and Tanambogo.

At 9:10 AM, August 7, 1942, the first wave of Marines of Combat Group A scrambled ashore on Guadalcanal between Koli Point and Lunga Point, quickly establishing a 2,000-yard-long, 600-yard-deep beachhead. Their surprise arrival met no organized Japanese ground resistance. Approximately 2,500 laborers, mostly Korean, of the 11th and 13th Construction Unit along with the few dozen regular Japanese soldiers melted into the island’s hinterland as the Americans came ashore. The only threats to the leathernecks that day came from a number of mostly ineffective Japanese air raids launched from Rabaul. By nightfall the Americans had carved out a mile-deep toehold on Guadalcanal. They halted for the night about 1,000 yards from the unfinished Japanese airfield near Lunga Point. The next day, August 8, the Marines, meeting only sporadic enemy resistance, advanced to the Lunga River and at 4 PM captured the airdrome.

The main Marine force that came ashore on Guadalcanal encountered more difficulty with the island’s foreboding jungle terrain, oppressively hot weather, and the confusion the inexperienced Americans had with offloading men and supplies than it did with the Japanese. It was a different and deadly story for General Rupertus’s command, which hit the beaches at Tulagi, Gavutu, and Tanambogo that same day.

At 6:52 AM on the morning of August 7, 1942, Japanese troops on Tulagi began to send a flood of radio transmissions in the clear reporting 20 enemy ships shelling the island accompanied by air attacks and seaborne forces. At 8:05 AM, Tulagi signaled that the island’s defenders were destroying their papers and equipment and signed off with the message, “Enemy troop strength is overwhelming. We pray for enduring fortunes of war,” and pledged to fight “to the last man.”

The Japanese garrison on Tulagi consisted of a 350-man detachment of the 3rd Kure SNLF under Commander Masaaki Suzuki, 536 naval members of the Yokohama Air Group, and some Japanese and Korean civilians from the 14th Construction Unit. About 900 soldiers under the supervision of Captain Shigetoshi Miyazaki, commander of the seaplane-equipped Yokohama Air Group, were in residence on Gavutu and Tanambogo. Making good on their promise, the Japanese on Tulagi did fight almost to the last man while exacting a heavy price on their American opponents.

The Marines assaulting Tulagi were carried to their objective by Transport Group Yoke, consisting of three troop transports, four Navy transport-destroyers, and one cargo ship. The landing force was made up of the 1st Raider Battalion; 1st Battalion, 2nd Marine Regiment; 2nd Battalion, 5th Marine Regiment; and 1st Parachute Battalion. These were the best trained units in the division and expected a tough fight. That assumption, which proved to be spot on, was based on prebattle intelligence assessments that Tulagi and the other islands were held by several hundred elite Japanese SNLF personnel of proven fighting ability who were well dug in.

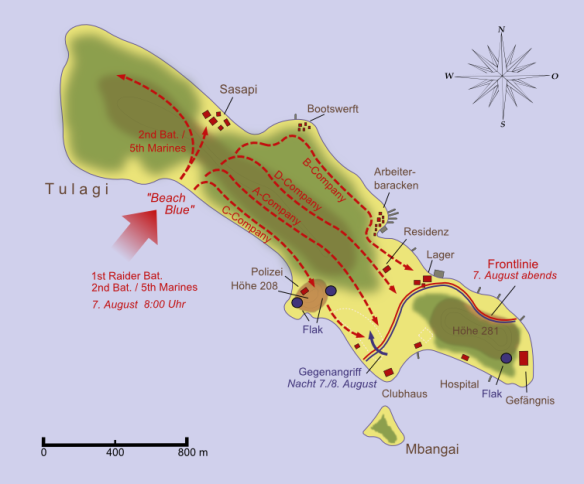

Preinvasion aerial reconnaissance revealed that the strongest defenses on Tulagi fronted the northeast and southeast shorelines. Therefore, the Marines selected a 500-yard stretch of beach (named Beach Blue) midway on the southwest side of the island for the landing. The invasion plan called for elements of the 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines to secure flanking positions on Florida Island followed by the 1st Raiders and then the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines going ashore on Tulagi. The idea was to make the first American amphibious assault of the war against natural obstacles instead of enemy firepower.

Four hours after American troops hit the beach on Tulagi, the parachutists were to have gained control of Gavutu and Tanambogo. Lt. Col. Merritt A. “Red Mike” Edson, chief of the Raider Battalion, offered to make a reconnaissance of the objectives on Tulagi prior to the operation, but the idea was rejected since it might alert the Japanese to the impending landing. As a result, the Marines would be landing with little concrete information on Japanese dispositions and strength.

At 7:40 AM, Company B, 1st Battalion, 2nd Marines, under Captain Edward J. Crane, made an unopposed landing near Haleta on Florida Island guided by three Australians, all former colonial officials who were familiar with the area. The rest of Company B’s parent unit, led by Lt. Col. Robert E. Hill, waded ashore on Florida’s Halavo peninsula east of Gavutu and Tanambogo. Both parties secured the high ground overlooking Blue Beach on Tulagi, and neither encountered any opposing forces.

At 8 AM, Edson’s 1st Raider Battalion grounded on an undetected coral reef 100 yards from Tulagi’s shoreline, forcing them to wade that distance to reach the beach. No enemy resistance was met at first since the Japanese garrison on the island believed that the naval bombardment and air attacks only signaled a hit-and-run raid and took shelter in caves. A solid defense was not mounted until later on the afternoon of the 7th.

In the meantime, the battalion’s leading companies pushed across the island and crested its spine. Company B then wheeled to the right while Company D moved right of Company B. Company A soon tied in with Company B, while Company C extended the entire Marine line to the island’s southwest shore. At around noon the Raiders swept down the island to their preinvasion designated Phase Line A, where Company C met the first enemy resistance from the Japanese outpost line.

Brief firefights eliminated these pockets of resistance, but not before the death of a Marine doctor and the wounding of Company C’s commander, Major Kenneth D. Bailey. Meanwhile, at 9:16 AM, Lt. Col. Harold E. Rosecrans’s 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines landed at Blue Beach, relieving Edson’s Company E, which was guarding the landing zone. The newly arrived 5th Marines then combed the northwest end of the island but found no Japanese.

Close to dusk, as the Raiders attempted to move beyond Phase Line A, Company C ran into heavy Japanese machine-gun fire near Hill 208. Commander Suzuki had formed his forward tripwire line on the hill’s steep slopes, which ran down to a ravine on its western edge. Farther to the east, he had set up his main line of resistance running from Hill 281 on the northeast coast of Tulagi through flat land that had been used as a cricket field in peaceful times to the southeast tip of the island.

Cunningly constructed dugouts and tunnels carved into the hill’s limestone cliffs and covered by machine-gun pits protected by sandbags made up this strong and well-concealed Japanese defensive position. The Japanese subsequently employed tactics that became hallmarks of their savage defense of Pacific island strongholds, including ambushes, the plentiful use of snipers, savage nocturnal counterattacks, and stealthy infiltration of American lines by small groups of Japanese soldiers.

During the afternoon and evening, Marines rooted out stubborn Japanese defenders with small arms and hand grenades. The Americans at this point in the war did not possess flamethrowers or purpose-built explosive devices, so they had to improvise, and that took time and cost lives. After disposing of the enemy’s forward defense line, Companies C and A moved a little farther to the east. The gathering darkness precluded a Marine attempt to clear the apparently strong and unidentified enemy positions of the main defensive line, so the Raiders dug in for the night.

About 10 PM , the Japanese mounted a fierce counterattack, driving a wedge between Company C and Company A, almost isolating the former from the rest of the battalion. Savage assaults against Company A’s exposed flank were were fended off. A second banzai attack, which might have successfully exploited the initial thrust, fell on the front of Company A and was bloodily repulsed.

The Japanese reverted to using infiltration tactics. Throughout the remainder of the night they slipped individuals and small groups into the rear of the American lines. They attacked the aid station and the command post of the 2nd Battalion, 5th Marines on Blue Beach. In addition, during the early hours of the 8th, Japanese infiltrators made five separate attacks on and near Raider battalion headquarters at the governor’s residence. The attackers were wiped out in hand to hand fighting. During the desperate fighting near the battalion command post, Colonel Edson tried to summon reinforcements, but his radio communications were out.

Later that morning, reinforced by Company’s E and F, 5th Marines, which landed on the north shore above Hill 281, and by 2nd Battalion, 2nd Marines, which reinforced the main U. S. line moving east along Tulagi, the leathernecks surrounded Hill 281 and the ravine sheltering their foe. After delivering lengthy barrages of 60mm and 81mm mortar fire, they used improvised TNT explosive devices to eliminate the numerous Japanese positions. By 3 PM, the tenacious and often suicidal Japanese resistance on Tulagi was broken. The battle had cost the Marines 45 dead and 76 wounded. The Japanese suffered 347 killed and just three captured. Japanese prisoners reported that about 40 to 70 Japanese soldiers had escaped Tulagi by swimming to Florida Island. Over the next two months, they were hunted down by Marines and native patrols.