By the time General Vasily Chuikov, the previous deputy commander of the 64th Army positioned south of Stalingrad, was appointed as commander of the 62nd Army, the 62nd Army had lost half of its men. For some, the Volga appeared to be the best means of escaping certain death. Chuikov knew that the situation was desperate and that the only options for him and his men were to save Stalingrad or die in the attempt. Defeat or surrender was not even to be considered.

The city’s defenders learned that secret police were stationed all along the Volga; anyone who attempted to cross the river without permission would be shot on sight. But the Volga was also bringing reinforcements of fresh troops and elite units. Crossing the river under German fire meant that the crossing itself was a death sentence—the typical life expectancy of a soldier arriving to reinforce the city was twenty-four hours—but the carnage allowed Chuikov to maintain a hold on part of the city.

The elite 13th Guard Division saw 30% of its 10,000 men killed in the first twenty-four of arrival, with a mere 320 surviving the battle for a 97% death rate. The risk of death was so imminent that even Chuikov was obliged to keep moving his command post from place to place at the last minute, to avoid being a casualty of the intense fighting that saw attacks staged along a front line that was sometimes less than a mile wide.

But the deadly dimensions of the battle were part of Chuikov’s strategy. By keeping the gap between Russian and German positions as narrow as possible, Chuikov reasoned that the German air campaign had to exercise caution in their bombing or risk killing their men when they dropped bombs on the Soviet line.

Starving soldiers are desperate men and because crossing the Volga was so dangerous, food was not entering the city, only more soldiers. The Russians weren’t the only ones suffering the lack of food, an issue which would become a dominant factor for the Germans as the battle continued. The fighting took its toll on the Germans, as they saw their initial advantage with their tanks and dive bombers come to be matched by Russian artillery reinforcements and anti-aircraft guns from east of the Volga River, out of range of the German tanks and the Stuka dive bombers. With trial-by-fire training, the Russian Air Force was able to be more offensive in its attacks, thanks to its increased aircraft.

Life in Stalingrad was a nightmare for the soldiers and civilians as the city was reduced to rubble. Bodies rotted, and the smell of decomposing corpses hung over the city. Disease became rampant. The noise from the Stuka dive bombers and Katyusha rockets created a grim orchestra of war. It was a scenario that challenged the stamina and even the sanity of all who endured it because there was no escaping the daunting consequences.

Generalleutnant Fiebig’s Fliegerkorps VIII, meanwhile, provided the army with effective air support. It struck enemy troops, vehicles, guns and fortified positions on the battlefield, as well as logistics and mobilization centres and road, rail and river traffic behind the front.

Throughout September, Fiebig’s corps directed most of its attacks against Stalingrad itself, the main targets being the Lazur chemical factory inside the “tennis racket” (a huge rail loop), the Krasnyi Oktyabr (Red October) metallurgical works, the Barrikady (Barricade) gun factory and the Dzherzhinski tractor factory. The corps pounded those targets most days, except when aircraft were urgently needed to support an Axis advance or stem a Soviet counter-attack in the region north of the city. On 18 September, for example, Lieutenant-General Chuikov noticed that the German aircraft crowding the sky above Stalingrad suddenly departed, giving Sixty-Second Army a much-needed “breathing space”. Fiebig had hastily called them away, he realized, in order to deploy them in the region north of the city, where they were urgently needed to counter a surprise attack by the Stalingrad Front. Six hours later, Chuikov noted with disappointment, “it was clear that the [Soviet] attack was over: hundreds of Junkers had reappeared.”

Chuikov quickly noticed that the Luftwaffe carried out surprisingly few raids at night. He could not work out, therefore, why the Stalingrad Front attempted its attacks during the day, “when we had no way of neutralizing or compensating for the enemy’s superiority in the air, and not at night (when the Luftwaffe did not operate with any strength).” The city’s defenders did not make the same mistake, he added later in his memoirs: “The enemy could not fight at night, but we learned to do so out of bitter necessity; by day the enemy’s planes hung over our troops, preventing them from raising their heads. At night we need have no fear of the Luftwaffe”. This was certainly true: at Stalingrad, as at Sevastopol, the Luftwaffe conducted almost no night missions to speak of. Its aircraft lacked the specialized night navigation and bomb-aiming equipment necessary for situations like this, when opposing forces battled in close proximity. Also, its airfields, with a few exceptions, were poorly equipped for night operations.

Fiebig’s air corps also bombed and strafed any Soviet forces seen among the broken buildings and piles of rubble. Chuikov recalled that “the Luftwaffe literally hammered anything they saw in the streets into the ground”. In his detailed memoirs, he also quotes the situation report of a young lieutenant, whose company came under severe air attacks on 18 September. “From morning till noon,” Lieutenant A. Kuzmich Dragan wrote,

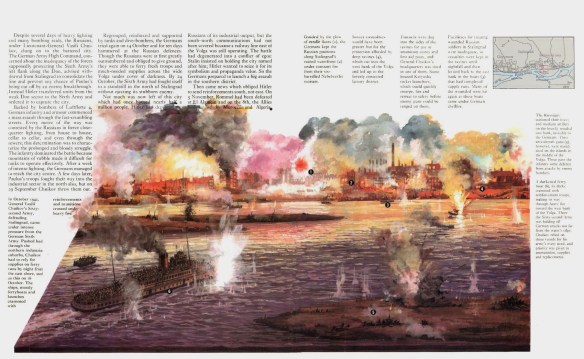

clusters of German planes hung in the sky over the city. Some of them would break away from their formations, dive and riddle the streets and ruins of houses with bullets from ground level; others would fly over the city with sirens wailing, in an attempt to sow panic. They dropped high explosives and incendiaries. The city was in flames.

Determined to support German troops now fighting for every house and building by stopping the steady trickle of Soviet reinforcements entering the city from the eastern bank of the kilometre-wide Volga river, Fiebig’s corps also directed attacks against the river crossing facilities. Rear-Admiral Rogachev’s Volga Fleet used numerous crossing points, but mainly “Crossing 62”, its moorings at the Krasnyi Oktyabr and Barrikady factories. The small fleet ferried substantial numbers of men and large quantities of rations and ammunition across the river to the desperate Sixty-Second Army. These courageous sailors, Chuikov maintained, “rendered an incalculable service…. Every trip across the Volga involved a tremendous risk, but no boat or steamer ever lingered with its cargo on the other bank.” Had it not been for them, he concluded, the Sixty-Second Army would almost certainly have perished in September.

Alan Clark, British author of a now-outdated popular account of the war in Russia, maintained that, if the Luftwaffe “had been employed with single-minded persistence in an “interdiction” role … the Volga ferries might have been knocked out.” Clark was clearly unaware of Luftflotte IV’s poor state when he wrote these words. Von Richthofen had no aircraft available for a proper interdiction campaign against the Volga crossings. As noted above, by 20 September his air fleet had already lost half its total strength and, because of a drop in serviceability levels, had a mere 516 air-worthy planes (when Blau began, it had 1,155). Moreover, 120 of those were reconnaissance and sea planes, leaving him with only 396 operational combat aircraft. With this small force, he was already extremely hard-pressed to fulfil his army-support obligations. Having stripped Pflugbeil’s Fliegerkorps IV to the bones in order to concentrate an acceptable number of aircraft at Stalingrad, he had left the two German armies in the Caucasus with very little air support and could only increase it during times of crisis by returning units temporarily from the Stalingrad region. Thus, he could spare no aircraft for a systematic interdiction campaign against Volga crossings.

Fliegerkorps VIII did not ignore the crossings, of course. Both Fiebig and von Richthofen realized that, if Paulus’ men were going to destroy the enemy troops fighting fanatically in the ruined city, they had to sever their supply and reinforcement lines. Although they lacked aircraft for a proper interdiction campaign, they continually threw as many bombers and dive-bombers as they could spare each day against the railway lines carrying men and materiel to the eastern bank of the Volga, against the exposed and poorly-defended loading and landing platforms and against any barges and steamers seen crossing the river. Fiebig often managed to keep aircraft continuously above the crossing points. As Chuikov remembered: “From dawn till dusk enemy dive-bombers circled over the Volga” Likewise, Lieutenant-Colonel Vladimirov noted in 1943:

The enemy bombers, operating in groups of 10 to 50, ceaselessly bombed our troops, the eastern part of the city and the crossings on the Volga…. The Germans relied on their aircraft to crush the fire system of our defence [that is, the artillery], paralyze our organization, prevent the arrival of reinforcements, and disrupt the movements of supplies.

German aircraft hunted down each boat and barge, but, as the discussion of air attacks on Black Sea shipping revealed, sinking ships from the air was extremely difficult. The relatively small size of Volga barges and ferries made them difficult targets. As a result, Fiebig’s dive-bombers proved far more successful against rail-heads and ferry landing platforms than they did against the vessels themselves.

The doomed Germans soldiers fought on bravely as best they could given their weakened physical conditions and lack of supplies; they had little choice. The Soviet offensive named Operation Saturn got underway on December 16 1942 with the purpose of bringing the final stage of the battle to its conclusion as relief efforts were made impossible and the trapped Germans were contained in a shrinking position. General Winter had frozen the Volga River allowing soldiers and supplies to travel over the ice into the city.

20160510 Grau – River Flotillas in Support of Defensive Ground Operations The Soviet Experience