In his statement to us at Viazma in the middle of September, General Sokolovsky had made three important points: first, that despite terrible setbacks the Red Army was gradually “grinding down” the Wehrmacht; secondly that it was very likely that the Germans would make one last desperate attempt, or even “several last desperate attempts” to capture Moscow, but they would fail in this; and, thirdly, that the Red Army was well-clothed for a winter campaign.

The impression that the Russians were rapidly learning all kinds of lessons, were dismissing as useless some of the pre-war theories, which were wholly inapplicable to prevailing conditions, and that professional soldiers of the highest order were taking over the command from the Army “politicians” and the “civil war legends” like Budienny and Voroshilov was to be confirmed in the next few weeks. Some brilliant soldiers had survived the Army Purges of 1937–8, notably Zhukov and Shaposhnikov, and had continued at their posts during the worst time of the German invasion; Zhukov had literally saved Leningrad in the nick of time by taking over from Voroshilov when all seemed lost. Apart from him and Shaposhnikov, Timoshenko—a first-class staff officer who had started his career in the Tsar’s army—was almost the only one of the pre-war top brass to prove a man of ability and imagination.

The first months of the war had been a school of the greatest value to the officers of the Red Army, and it was above all those who had distinguished themselves in the operations of June to October 1941 who were to form that brilliant pléiade of generals and marshals the like of whom had not been seen since Napoleon’s Grande Armée. In the course of the summer and autumn important changes had been made in the organisation of the air force by General Novikov, and in the use of artillery by General Voronov; both Zhukov and Konev had played a leading role in holding up the Germans at Smolensk; Rokossovsky, Vatutin, Cherniakhovsky, Rotmistrov, Boldin, Malinovsky, Fedyuninsky, Govorov, Meretskov, Yeremenko, Belov, Lelushenko, Bagramian and numerous other men, who were to become famous during the Battle of Moscow or in other important battles in 1941, were men who had, as it were, won their spurs in the heavy fighting during the first months of the war. Distinction in the field now became Stalin’s criterion in making top army appointments. It is, indeed, perfectly true that “the summer and autumn battles had brought on a military purge, as opposed to a political purge of the military. There was a growing restlessness with the incompetent and the inept. The great and signal strength of the Soviet High Command was that it was able to produce that minimum of high calibre commanders capable of steering the Red Army out of total disaster”.

Undoubtedly some of the commanders had only a purely nominal Party affiliation, and some of the new men, such as Rokossovsky, had actually been victims of the Army Purges of 1937–8, and so could not have had any tender feelings for Stalin.

The Stavka, the General Headquarters of the Soviet High Command was set up on June 23, and a few days later the State Defence Committee (GKO), consisting of Stalin, Molotov, Voroshilov, Malenkov and Beria; on July 10 the “Stavka of the High Command” became the “Stavka of the Supreme Command”, with Stalin, Molotov, Voroshilov, Budienny, Shaposhnikov and General Zhukov, the Chief of Staff, as members. On July 19 Stalin became Defence Commissar and on August 7 Commander-in-Chief.

The Commissar system was greatly reinforced; the commissars, as “representatives of the Party and the government in the Red Army” were to watch over the officers’ and soldiers’ morale, and share with the commander full responsibility for the unit’s conduct in battle. They were also to report to the Supreme Command any cases of “unworthiness” amongst either officers or political personnel. This was a hangover from the civil war, and, indeed, from the much more recent period when the officer corps was suspected of unreliability. In practice, in 1941, the commissars proved, in the great majority of cases, to be either men who almost fully supported the officers, or were, at most, a minor technical nuisance; but inspired by the same lutte à outrance spirit, and, faced daily by pressing military tasks, the old political and personal differences between officer and commissar were now usually less harsh than in the past. Even so, the dual command had its drawbacks, and, at the time of Stalingrad, the commissars’ role was to be drastically modified.

Whether or not there was any serious need for giving the officer a “Party whip”, there was certainly even less need for the NKVD’s “rear security units” to check panic through the use of machine-gunners ready to keep the Red Army from any unauthorised withdrawals. “What initial fears there might have been that the troops would not fight were soon dispelled by the stubborn and bitter defence which the Red Army put up against the Germans, fighting, as Halder observed, ‘to the last man’, and employing ‘treacherous methods’ in which the Russian did not cease firing until he was dead”. These “rear security units” were a revival of a practice inherited from the Civil War, and proved wholly unnecessary in 1941, the Army itself dealing rigorously with any cases of cowardice and panic.

The role of the NKVD in actual military operations remains rather obscure, though it is known that, apart from the Frontier Guards, who were under NKVD jurisdiction, and who were the first to meet the German onslaught, there were to be some very important occasions in which NKVD troops fought as battle units—for example at Voronezh in June–July 1942, where they helped to prevent a particularly dangerous German breakthrough. But there was a much grimmer side to the NKVD’s connection with the Red Army; thus, not only Russian prisoners who had managed to escape from the Germans, but even whole Army units who—as so often happened in 1941—had broken out of German encirclement, were subjected as suspects to the most harsh and petty interrogation by the O.O. (Osoby Otdel—Special Department) run by the NKVD. In Simonov’s novel, The Living and the Dead, there is a particularly sickening episode based on actual fact, in which a large number of officers and soldiers break out of a German encirclement after many weeks’ fighting. They are promptly disarmed by the NKVD; but it so happens that at that very moment the Germans have started their offensive against Moscow, and as the disarmed men are being taken to a NKVD sorting station, they are trapped by the Germans, and simply massacred, unable to offer any resistance.

Apart from that, however, the NKVD interfered less than before with the Red Army; the border-line between the military and the “political” elements in the Army was vanishing, and Stalin himself presided over this development. Whatever he had done in the past to weaken the army by his purges and his constant political interference, he had learned his lesson from the summer and autumn of 1941. Voroshilov and Budienny were pushed into the background and the role of the NKVD bosses greatly reduced. The patriotic, nationalist and “1812” line was wholeheartedly taken up by all ranks of the army. All the military talent—discovered and tested in the first battles of the war and, in some cases, before that in the Far East—was assembled, all available reserves were thrown into battle, including some crack divisions from Central Asia and the Far East, a measure made possible by the Non-Aggression Pact concluded with the Japanese in 1939.

Whatever bad memories and reservations the generals may have had, Stalin had become the indispensable unifying factor in the patrie-en-danger atmosphere of October–November 1941. There was no alternative. The Germans were on the outskirts of Leningrad, were pushing through the Donbas on their way to Rostov, and on September 30 the “final” offensive against Moscow had started.

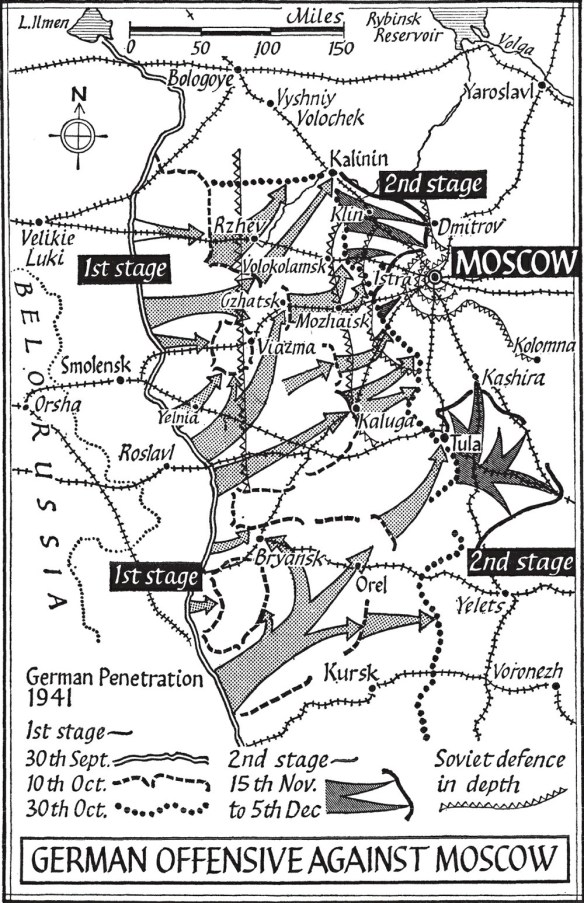

The Battle of Moscow falls, broadly, into three phases: the first German offensive from September 30 to nearly the end of October; the second German offensive from November 17 right up to December 5; and the Russian counter-offensive of December 6, which lasted till spring 1942.

On September 30 Guderian’s panzer units on the southern flank of Heeresgruppe Mitte (Army Group Centre) thrust against Glukhov and Orel, which fell on October 2, but were then held up by a tank group under Colonel Katyukov beyond Mtsensk, on the road to Tula. Other German forces launched full scale attacks from the south-west in the Bryansk area and from the west on the Smolensk-Moscow road. Large Soviet troop concentrations were encircled south of Bryansk and in the Viazma area due west of Moscow. The Germans had planned to contain Soviet troops surrounded in the Viazma area mainly by infantry, thus freeing their panzer and motorised divisions for a lightning advance on Moscow. But for more than a week, fighting a circular battle of extreme ferocity, the remnants of the 19th, 20th, 24th and 32nd Armies and the troops under General Boldin tied up most of the German 4th Army and of the 4th Tank Corps. This resistance enabled the Soviet Supreme Command to extricate and withdraw more of their front line troops from the encirclement to the Mozhaisk line and to bring up reserves from the rear.

By October 6 German tank units had broken through the Rzhev-Viazma defence line and were advancing towards the Mozhaisk line of fortified positions some fifty miles west of Moscow, which had been improvised and prepared during the summer of 1941, and ran from Kalinin (north-west of Moscow on the Moscow-Leningrad Railway line), to Kaluga (south-west of Moscow and half-way between Tula and Viazma), Maloyaroslavets and Tula. The few troops manning these defences could halt the advance units of the Heeresgruppe Mitte, but not the bulk of the German forces.

While reinforcements from the Far East and Central Asia were on their way to the Moscow Front, the GKO Headquarters threw in what reserves they could muster. The infantry of Generals Artemiev and Lelushenko and the tanks of General Kurkin which fought here were, by October 9, placed under the direct orders of the Soviet Supreme Command. On the following day Zhukov was appointed C. in C. of the whole front.

But the Germans bypassed the Mozhaisk line from the south and captured Kaluga on October 12. Two days later, outflanking the Mozhaisk line in the north, they broke into Kalinin. After heavy fighting Mozhaisk itself was abandoned on October 18. Already on the 14th fierce battles were raging in the Volokolamsk sector, midway between Mozhaisk and Kalinin, some fifty miles north-west of Moscow.

The situation was extremely serious. There was no continuous front any more. The German air force was master of the sky. German tank units, penetrating deep into the rear, were forcing the Red Army units to retreat to new positions to avoid encirclement. Together with the army, thousands of Soviet civilians were moving east. People on foot, or in horse carts, cattle, cars, were moving east in a continuous stream along all the roads, making troop movements even more difficult.

Despite stiff resistance everywhere, the Germans were closing in on Moscow from all directions. It was two days after the fall of Kalinin, and when the threat of a breakthrough from Volokolamsk to Istra and Moscow looked a near-certainty, that the “Moscow panic” reached its height. This was on October 16. To this day the story is current that, on that morning, two German tanks broke into Khimki, a northern suburb of Moscow, where they were promptly destroyed; that two such tanks ever existed, except in some frightened Muscovite’s imagination, is not confirmed by any serious source.

What happened in Moscow on October 16? Many have spoken of the big skedaddle (bolshoi drap) that took place that day. Although, as we shall see, this is an over-generalisation, October 16 in Moscow was certainly not a tale of the “unanimous heroism of the people of Moscow” as recorded in the official History.

It took the Moscow population several days to realise how serious the new German offensive was. During the last days of September and, indeed, for the first few days of October, all attention was centred on the big German offensive in the Ukraine, the news of the breakthrough into the Crimea, and the Beaverbrook visit, which had begun on September 29. At his press conference on September 28 Lozovsky had tried to sound very reassuring, saying that the Germans were losing “many tens of thousands dead” outside Leningrad, but that no matter how many more they lost, they still wouldn’t get into Leningrad; he also said that “communications continued to be maintained”, and that, although there was rationing in the city, there was no food shortage. He also said that there was heavy fighting “for the Crimea”, but denied that the Germans had as yet crossed the Perekop Isthmus. As for the German claim of having captured 500,000 or 600,000 prisoners in the Ukraine, after the loss of Kiev, he was much more cagey, saying that the battle was continuing, and that it was not in the Russian’s interest to give out information prematurely. However, he added the somewhat sinister phrase: “The farther east the Germans push, the nearer will they get to the grave of Nazi Germany.” He seemed to be prepared for the loss of Kharkov and the Donbas, though he did not say so.

It did not become clear until October 4 or 5 that an offensive against Moscow had started, and, even so, it was not clear how big it was. There was, needless to say, nothing in the Russian papers about Hitler’s speech of October 2 announcing his “final” drive against Moscow.

However, Lozovsky referred to it in his press conference of October 7. He looked slightly flustered, but said that Hitler’s speech only showed that the fellow was getting desperate.

“He knows he isn’t going to win the war, but he has to keep the Germans more or less contented during the winter, and he must therefore achieve some major success, which would suggest that a certain stage of the war has closed. The second reason why it is essential for Hitler to do something big is the Anglo-American-Soviet agreement, which has caused a feeling of despondency in Germany. The Germans could, at a pinch, swallow a ‘Bolshevik’ agreement with Britain, but a ‘Bolshevik’ agreement with America was more than the Germans had ever expected.” Lozovsky added that, anyway, the capture of this or that city would not affect the final outcome of the war. It was as if he was already preparing the press for the possible loss of Moscow. Yet he managed to end on a note of bravado: “If the Germans want to see a few hundred thousand more of their people killed, they’ll succeed in that—if in nothing else.”

The news on the night of the 7th was even worse, with the first official reference to “heavy fighting in the direction of Viazma”.

On the 8th, while Pravda and Izvestia were careful not to sound too alarmed (Pravda actually started with a routine article on “The Work of Women in War-Time”), the army paper, Red Star, looked extremely disquieting. It said that “the very existence of the Soviet State was in danger”, and that every man of the Red Army “must stand firm and fight to the last drop of blood”. It described the new German offensive as a last desperate fling:

Hitler has thrown into it everything he has got—even every old and obsolete tank, every midget tank the Germans have collected in Holland, France or Belgium has been thrown into this battle… The Soviet soldiers must at any price destroy these tanks, old and new, large or small. All the riff-raff armour of ruined Europe is being thrown against the Soviet Union.

Pravda sounded the alarm on the 9th, warning the people of Moscow against “careless complacency” and calling on them to “mobilise all their forces to repel the enemy’s offensive”. On the following day it called for “vigilance” saying that, in addition to advancing on Moscow, “the enemy is also trying, through the wide network of its agents, spies and agents-provocateurs, to disorganise the rear and to create panic”. On October 12, Pravda spoke of the “terrible danger” threatening the country.

Even without the help of enemy agents, there was enough in Pravda to spread the greatest alarm among the population of Moscow. Talk of evacuation had begun on the 8th, and foreign embassies as well as numerous Russian government offices and institutions were told to expect a decision on it very shortly. The atmosphere was becoming extremely tense. There was talk of Moscow as a “super-Madrid” among the braver, and feverish attempts to get away among the less brave.

By October 13, the situation in Moscow had become highly critical. Numerous German troops which had, for over a week, been held up by the “Viazma encirclement”, had become available for the final attack on Moscow. The “Western” Front, under the general command of General Zhukov, assisted by General Konev, and with General Sokolovsky as Chief of Staff, consisted of four sectors: Volokolamsk under Rokossovsky; Mozhaisk under Govorov, Maloyaroslavets under Golubev and Kaluga under Zakharkin. There was absolutely no certainty that a German breakthrough could be prevented, and on October 12, the State Defence Committee had decided to call upon the people of Moscow to build a defence line some distance outside Moscow, another one right along the city border, and two supplementary city lines along the outer and inner rings of boulevards within Moscow itself.

On the morning of October 13, Shcherbakov, Secretary of the Central Committee and of the Moscow Party Committee of the Communist Party, spoke at a meeting called by the Moscow Party Organisation: “Let us not shut our eyes. Moscow is in danger.” He appealed to the workers of the city to send all possible reserves to the front and to the defence lines both inside and outside the city; and to increase greatly the output of arms and munitions.

The resolution passed by the Moscow Organisation called for “iron discipline, a merciless struggle against even the slightest manifestations of panic, against cowards, deserters and rumour-mongers”. The resolution further decided that, within two or three days, each Moscow district should assemble a battalion of volunteers; these came to be known as Moscow’s “Communist Battalions” and were, like some of the opolcheniye regiments, to play an important role in the defence of Moscow by filling in “gaps”—at a very heavy cost in lives. Within three days, 12,000 such volunteers were formed into platoons and battalions, most of them with little military training and no fighting experience.

It was on October 12 and 13 that it was decided to evacuate immediately to Kuibyshev and other cities in the east a large number of government offices, including many People’s Commissariats, part of the Party organisations, and the entire diplomatic corps of Moscow. Moscow’s most important armaments works were to be evacuated as well. Practically all “scientific and cultural institutions” such as the Academy of Sciences, the University and the theatres were to be moved.

But the State Defence Committee, the Stavka of the Supreme Command, and a skeleton administration were to stay on in Moscow until further notice. The principal newspapers such as Pravda, Red Star, Izvestia, Komsomolskaya Pravda, and Trud, continued to be published in the capital.

The news of these evacuations was followed by the official communiqué published on the morning of October 16. It said: “During the night of October 14–15 the position on the Western Front became worse. The German-Fascist troops hurled against our troops large quantities of tanks and motorised infantry, and in one sector broke through our defences.”

In describing the great October crisis in Moscow it is important to distinguish between three factors. First, the Army, which fought on desperately against superior enemy forces, and yielded ground only very slowly, although owing to relatively poor maneuverability, it was unable to prevent some spectacular German local successes, such as the capture of Kaluga in the south on the 12th, of Kalinin in the north on the 14th, or that breakthrough in what was rather vaguely described as “the Volokolamsk sector” to which the “panic communiqué”, published on October 16, referred. Even long afterwards it was believed in Moscow that on the 15th the Germans had crashed through much further towards Moscow than is apparent today from any published record of the fighting. Only then, it was said, did Rokossovsky stop the rot by throwing in the last reserves, including scarcely-trained opolchentsy, and troops from Siberia as soon as they disembarked from the trains. There are countless stories of regular soldiers and even opolchentsy attacking German tanks with hand grenades and with “petrol bottles”, and of other “last ditch” exploits. The morale of the fighting forces certainly did not crack. The fact that fresh troops from the Far East and Central Asia were being thrown in all the time, though only in limited numbers, had a salutary effect in keeping up the spirit of the troops who had already fought without respite for over a fortnight.

Secondly, there was the Moscow working-class; most of them were ready to put in long hours of overtime in factories producing armaments and ammunition; to build defences; to fight the Germans inside Moscow should they break through, or, if all failed, to “follow the Red Army to the east”. However, there were different shades in the determination of the workers to “defend Moscow” at all costs. The very fact that not more than 12,000 should have volunteered for the “Communist brigades” at the height of the near-panic of October 13–16 seems indicative; was it because, to many, these improvised battalions seemed futile in this kind of war, or was it because, at the back of many workers’ minds, there was the idea that Russia was still vast, and that it might be more advantageous to fight the decisive battle somewhere east.

Thirdly, there was a large mass of Muscovites, difficult to classify, who were more responsible than the others for “the great skedaddle” of October 16. These included anybody from plain obyvateli, ready to run away from danger, to small, medium and even high Party or non-Party officials who felt that Moscow had become a job for the Army, and that there was not much that civilians could do. Among these people there was a genuine fear of finding themselves under German occupation, and, with regular passes, or with passes of sorts they had somehow wangled—or sometimes with no passes at all—people fled to the east, just as in Paris people had fled to the south in 1940 as the Germans approached the capital.

Later, many of these people were to be bitterly ashamed of having fled, of having overrated the might of the Germans, of having not had enough confidence in the Red Army. And yet, had not the Government shown the way, as it were, by frantically speeding up on all those evacuations from the 10th of October onwards?

Especially in 1942 the “big skedaddle” of October 16 continued to be a nasty memory with many. There were some grim jokes on the subject—especially in connection with the medal “For the Defence of Moscow” that had been distributed lavishly among the soldiers and civilians; there was the joke about the two kinds of ribbons—some Moscow medals should be suspended on the regular moiré ribbon, others on a drap ribbon—drap meaning both a thick kind of cloth and skedaddle. There was also the joke of a famous and very plump and well-equipped actress who had received a Moscow Medal “for defending Moscow from Kuibyshev with her breast”.

I remember Surkov telling me that when he arrived in Moscow from the front on the 16th, he phoned some fifteen or twenty of his friends, and all had vanished.

In “fiction”, more than in formal history, there are some valuable descriptions of Moscow at the height of the crisis—for instance in Simonov’s The Living and the Dead already quoted. Here is a picture of Moscow during that grim 16th of October and the following days—with the railway station stampedes; with officials fleeing in their cars without a permit; the opolchentsy and Communist battalion men sullenly walking, rather than marching, down the streets, dressed in a motley collection of clothes, smoking, but not singing; with the “Hammer and Sickle” factory working day and night turning out thousands of anti-tank hedge-hogs, which are then driven to the outer ring of boulevards; with its smell of burning papers; with the rapid succession of air-raids and air-battles over Moscow, in which Russian airmen often suicidally ram enemy planes; with the demoralisation of the majority and the grim determination among the minority to hang on to Moscow, and to fight, if necessary, inside the city.

By the 16th, many factories had already been evacuated.

All the same, below all the froth of panic and despair there was “another Moscow”:

Later, when all this belonged to the past, and somebody recalled that 16th of October with sorrow or bitterness, he [Simonov’s hero] would say nothing. The memory of Moscow that day was unbearable to him—like the face of a person you love distorted by fear. And yet, not only outside Moscow, where the troops were fighting and dying that day, but inside Moscow itself, there were enough people who were doing all within their power not to surrender it. And that was why Moscow was not lost. And yet, at the Front that day the war seemed to have taken a fatal turn, and there were people in Moscow that same day who, in their despair, were ready to believe that the Germans would enter Moscow tomorrow. As always happens in tragic moments, the deep faith and inconspicuous work of those who carried on, was not yet known to all, and had not yet come to bear fruit, while the bewilderment, terror and despair of the others hit you between the eyes. This was inevitable. That day tens of thousands, getting away from the Germans, rolled like avalanches towards the railway stations and towards the eastern exits of Moscow; and yet, out of these tens of thousands, there were perhaps only a few thousand whom history could rightly condemn.

Simonov wrote this account of Moscow on October 16, 1941 after a lapse of nearly twenty years; but his story—which could not have been published in Stalin’s day—rings true in the light of what I had heard of those grim days only a few months later, in 1942.

BY ALEXANDER WERTH 1964