This was a site between the second and first cataract of the Nile near WADI HALFA, settled as an outpost as early as the Second Dynasty (2770–2649 B.C.E.). This era was marked by fortifications and served as a boundary of Egypt and NUBIA (modern Sudan) in certain eras. The New Kingdom (1550–1070 B.C.E.) pharaohs built extensively at Buhen. A Middle Kingdom (2040–1640 B.C.E.) FORTRESS was also discovered on the site, with outer walls for defense, bastions, and two interior temples, following the normal pattern for such military structures in Egypt. HATSHEPSUT, the Queen- Pharaoh (r. 1473–1458 B.C.E.), constructed a temple in the southern part of Buhen, with a five-chambered sanctuary, surrounded by a colonnade. TUTHMOSIS III (r. 1479–1425 B.C.E.) renovated the temple, enclosing a complex and adding porticos.

The actual fortress of Buhen was an elaborate structure, built partly out of rock with brick additions. The fort was set back from the river, giving way to a rocky slope. These walls supported external buttresses, which were designed to turn south and east to the Nile. A ditch was added for defense, carved out of rock and having deep sides that sloped considerably and were smoothed to deter scaling attempts. A gateway in the south wall opened onto an interior military compound, which also contained the original temples. AMENHOTEP II (r. 1427–1391 B.C.E.) is credited with one shrine erected there.

#

The defence of Egypt and its soldiers took various forms, including defensive building works (such as fortresses, walls, and border posts), the use of personal shields by soldiers, and, arguably, through political manoeuvres by Egypt’s rulers. One of ancient Egypt’s largest defensive projects was the building of border fortresses. There were several examples of these built throughout Dynastic Egypt’s history on the orders of several pharaohs. One of the most famous Pharaohs, Ramesses II, ordered the building of a line of such fortresses along Egypt’s northwestern coast in a bid to prevent further infiltrations into his lands by the ‘Sea Peoples’.

As previously discussed, prior to the New Kingdom, Egypt usually had a policy of defending its existing borders rather than looking outwards at the state’s geographical and political expansion. As a result of this particular outlook, Egypt had no standing army, but instead relied almost exclusively on provincial militias and conscription when threatened with invasion. One example of this took place in the Sixth Dynasty (during the reign of Pepi I) when an attempted invasion by the ‘sand-dwellers’ or ‘Shasu’ threatened his eastern borders. The force raised by Pepi I was led by Weni, a court official with no previous military leadership experience. With numbers on his side Weni’s lack of experience was overcome, leading to a successful outcome for Egypt. Due to this Weni was then appointed as the army commander for at least four more operations against the ‘sand-dwellers’. It would seem that Pepi I was perfectly content to leave his army’s activities at defensive manoeuvres and had no desire, and perhaps no resources, to expand Egypt’s borders at that time. So did Old Kingdom military/defence attitudes influence the building of fortresses? Fortresses certainly do not seem to have been designed specifically for outward invasions.

Fortresses (rather than fortified towns) were built by the ancient Egyptians in order to guard and control Egypt’s vulnerable northern and southern frontiers. These, primarily mudbrick, structures could hold up to a few hundred troops (occasionally comprising Nubian, Philistine, or Libyan soldiers), serving for up to six years at a time. According to the Semna Papyri (reports that were sent by the commander of the fortress at Semna to the military headquarters at Thebes during the reign of Amenemhat III), these troops had to carry out surveillance and reconnaissance patrols of the surrounding areas at regular intervals. There were examples of fortresses (called the Walls of the Prince) that were built in the eastern Delta during the reign of Amenemhat I (1991-1962BC), which were designed to defend the coastal route from the Levant. This was at around the same time as a fortress was built at Wadi Natrun, which was designed to defend the western Delta region against invading Libyans. These sites were maintained and improved during the New Kingdom, perhaps as a way to prevent reinvasion by the Hyksos, who had ruled this area of Egypt in the Second Intermediate Period between the Middle Kingdom and the New Kingdom.

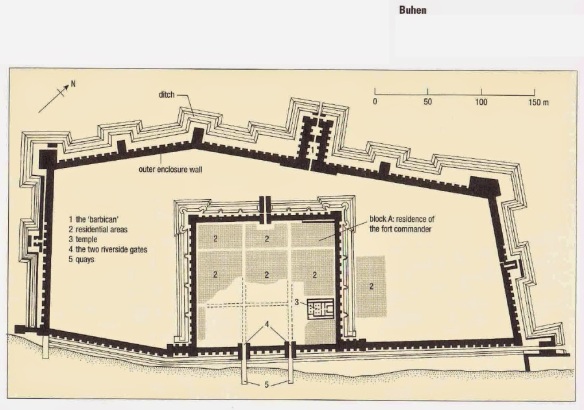

The mudbrick fortress of Buhen, in Lower Nubia (in the Second Cataract, 156 miles upstream of Aswan), is one of the most well-known and impressive of these structures. Buhen was one of the most elaborate of ancient Egypt’s fortresses and united all the Second Cataract fortresses under its command by the time of the New Kingdom. Initially founded in the Second Dynasty, the site was established early on as a trade centre, becoming known for copper-smelting in the Fourth and Fifth Dynasties. It was during the Middle Kingdom that the fortress was enlarged and strengthened in order to become a frontier fortress, one of a string of eleven in the area. These improvements took the form of mudbrick ramparts added to the 4m thick outer western wall, which itself incorporated five large towers. There was also a large central tower that served as the main entrance (comprising two openings with double wooden doors) and a drawbridge. The inner fortress was built along a more regular square plan and had towers at each corner along with bastions that were at 5-metre intervals.

While fortresses always played a defensive role to some extent, there are many interpretations as to their core role, both in terms of function and symbolism. Shaw is of the opinion that these Nubian fortresses were not designed for border defence but were, in fact, to protect Egypt’s monopoly on exotic trade goods (such as gold and ivory) which were brought up through Nubia into Egypt.412 Archaeologists generally believe that fortresses such as Buhen were designed for propaganda reasons, with elaborate crenellations, bastions, and ditches. As Buhen was built on flat ground with a square ground-plan it would have looked very impressive but, arguably, would have been difficult to defend effectively as it lacked any advantage, such as being built on top of a hill or other elevated land. Certainly by the New Kingdom, Buhen had become a primarily civilian settlement, as Egypt’s frontiers were pushed further south.

Arguments on their exact role aside, the importance of fortresses cannot be ignored and the erection of new fortresses (or rather forts and walls) continues long throughout the New Kingdom and beyond. Some of the most notable include the string of forts along the Mediterranean coast of the Delta that were commissioned by Ramesses II and the forts at Qasr Ibrim and Qasr Qarun that were built by the Roman rulers in the Graeco-Roman Period of Egypt’s history. During periods of great disturbance (such as the Third Intermediate Period and the Late Period) there was an increase in the building of fortifications. The Kushite King Piye even boasted on his stele at Gebel Barkal of his defeat of the Egyptians in 734BC, which includes a mention of Middle Egypt and its nineteen fortified settlements along with various walled cities in the Egyptian Delta.416 This boasting by Piye shows the importance of fortresses in the defence of ancient Egypt, at least in the minds of Egypt’s enemies.